Santa Maria Assunta (Brescia)

|

Facade of the new cathedral |

|

| Basic data | |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| place | Brescia, Italy |

| diocese | Diocese of Brescia |

| Patronage | Assumption Day |

| Building history | |

| construction time | 1604-1825 |

| Building description | |

| Architectural style | Baroque |

| 45 ° 32 '19 " N , 10 ° 13' 18.6" E | |

The new cathedral , or rather the summer cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta , is the main church of Brescia and the Chiesa Madre of the diocese of the same name . It is located in Piazza Paolo VI, formerly Piazza del Duomo. It was built between 1604 and 1825 on the site of the early Christian basilica of San Pietro de Dom (5th – 6th centuries).

It is also the seat of a parish belonging to the Brescia Centro area.

history

The history of the cathedral began in 1603 when Agostino Avanzo inspected the area for the construction of a new religious building to replace the early Christian basilica of San Pietro de Dom. The old basilica was in a dilapidated condition and had to be replaced by a new cathedral that better met the new architectural requirements of the Counter Reformation and the architecture of the time. Agostino Avanzo presented a first draft of the cathedral, a mixture of mannerism and classicism : the floor plan of a Latin cross with three naves and transept, protruding side altars and a large central dome . The latter in particular has prevailed from the earliest project ideas and has dominated the construction site over the centuries as a kind of great common goal that was strived for by all the architects who worked there.

Giovanni Battista Lantana , who had just finished his studies, presented, unlike the Avanzo, a fairly similar but more modern project with a greater focus on the overall structure. Both ideas, however, were rejected by the deputies of the building commission elected by the city council and the bishop, mainly because they did not adhere to the guidelines of the Council of Trent for the building of churches. Lantana presents a new design with the floor plan of a Greek cross , a large central dome surrounded by four smaller domes and a protruding apse, very similar to Bramante's for St. Peter's Basilica , but without the outer nave and only with the apse . This plan was approved by the Commission. The debates were not long in coming: there were also doubts about the position of the cathedral; H. whether it should be built in place of the Basilica of San Pietro de Dom or perhaps placed on the south side of the square to create a monumental baroque backdrop. At the place where the 19th century Palazzo der Credito Agrario Bresciano is today, there was a large villa with garden, the residence of the Negroboni, aristocrats from Brescia. In return for the transfer of the land and the subsequent destruction of the villa, the Negroboni family asked for another one with an adjacent park. In addition, the Basilica of San Pietro di Dom would remain, which would soon require a radical restoration. Then the cheapest solution was decided, namely to demolish the old basilica and build the new cathedral in its place.

At this point, further discussions were held: the Lantana plan was too similar to the old cathedral. The proposed Greek cross was too modern and still poorly understood by the clients and the population and again incompatible with the regulations of the Counter Reformation. However, this last problem was not so crucial: the floor plan of a Greek cross was elevated to a perfect form of religious architecture by practically all major Renaissance artists (from Leonardo da Vinci to Bramante to Antonio da Sangallo the Younger ) and was tangibly rooted in ideology, so that not even the Counter-Reformation has ever succeeded in counteracting it completely. With this in mind, the churches of Sant'Alessandro in Zebedia in Milan and Santa Maria di Carignano in Genoa were built in the form of a Greek cross in those years. It is likely that Lantana followed the plan of the Church of Carignano as the first stonemasons to work on the cathedral's construction site were the Orsolini from Genoa. Finally, Lantana proposed a third design, which turned out to be the final one: he added a small Tuscan order to the side of the great Corinthian order, and another dome was placed on the apse, supported by a few external buttresses interspersed with niches. For the latter, the work's clients have already commissioned decorative statues from Giovanni Antonio Carra, the founder of a famous family of sculptors from Brescia.

The foundation stone was laid in 1604, and immediately in front of it were the stonemasons' huts, which became a real school of sculpture and architecture that has always been missing in Brescia. The disputes did not let up, however: the focus was still on the question of the floor plan, which should ideally be converted into a Latin cross. At the head of the opponents was Pier Maria Bagnadore, but not for architectural reasons, but to hinder the competitor Lantana. He proposed an alternative plan, effectively a copy of the Lantana plan, with a single addition, an extension to the west that would turn the Greek cross into a Latin cross. The dispute won Bagnadore, who took on the role of construction manager, while Lantana remained responsible for the economic management of the site. But the rivalry between the two remained insurmountable: Everywhere and in every detail differences of opinion arose and the construction site remained closed for long periods of time. The construction project was subject to some changes: On the sides of the apse there were two buildings, one of which served as a rectory. The apse was therefore integrated between them and no longer protrudes, so that the dome of the cover no longer required buttresses. Even the outer niches to be adorned with the statues of Carra were reduced from perhaps five to two, and the sculptors only had to place the remaining statues of Saints Faustin and Jovita . In addition, not even Bagnadore, as the defender of the Latin cross, really recognized it: Another change he made changed the floor plan of the cathedral back to a Greek cross. The span was reduced and reduced to no more than two niches between the pylons of the opposite facade, which were not even connected to each other. The ongoing competition with Bagnadore and perhaps also his questionable, practically hypocritical behavior prompted Lantana to leave the construction site within a short time. The drop that made the barrel overflow, so to speak, seems to have been the arrival of Tommaso Lorando, a student of Lantana. He assisted the administration with the bookkeeping, likely questioning Lantana's ability in the field, and provoking his ultimate refusal to maintain the structure.

The construction site was again closed for a longer period of time. When Bagnadore returned to the Greek cross, the architect fell out of favor with Bishop Marino Giorgi and was replaced in 1611. He was replaced by Lorenzo Binago from Milan, builder of the Sant'Alessandro church in Zebedia. He was one of those who might have inspired Lantana's first design. The second phase of construction of the cathedral began: next to Binago there is Antonio Comino, another great representative of Brescian architecture and sculpture and the initiator of the reconstruction of the church of Santi Faustino e Giovita . Comino became a project manager while Binago remained an architect and site manager. A considerable number of construction plans were drawn up, supplemented by notes and explanations. The facade designed by Binago was baroque and flanked by two bell towers, as was common in religious buildings at the time. However, the latter solution was again too modern in the eyes of the population and the client, as a church with two towers had never been seen in Brescia. If they had been built there would have been four towers in the square: the two of the cathedral, the Torre del Popolo del Broletto and the bell tower of the old cathedral, which no longer exists because it collapsed in 1708. Theoretically, the idea would have served to “baroque” the square, but the time was not yet ripe and so the towers were never built.

The plague epidemic in northern Italy around 1630 and the resulting economic and demographic crisis also put a strain on the cathedral construction site and led to an interruption of almost forty years. Construction resumed in the second half of the 17th century, but it was not until the end of the century that it could be said that construction had finally continued. It is particularly noteworthy that the work was able to resume quite soon. This is due to all of the legacy that the Church has preserved from the huge number of deaths caused by the plague and that has placed the diocese of Brescia in the economic position to get the site back to work, even though the crisis was still raging outside the city. When the construction site was resumed, obviously everyone involved had changed and the third construction phase began. In 1698, Luca Serena, son of the painter Nicola Serena, designed a concept for the completion of the cathedral, as did Giuseppe Antonio Torri, a nationally famous artist at the time, who in 1711 also presented an apse roof in a hull shape that had never been built. A few years later Antonio Biasio became the new site manager and in 1719 he designed a new facade with a semicircular gable, which was very fashionable at the time, which replaced the Binago facade. The idea persisted until 1748, when Biasio again modified the gable in the form of a lowered arch and followed the taste of the time. During these years Cardinal Angelo Maria Quirini was Bishop of Brescia and gave the work a strong impetus.

Biasio died in 1758 and Giovanni Battista Marchetti took over the management of the construction site with his son Antonio. The facade, which was only completed in the lower half, was modified again and this time crowned with a triangular pediment in accordance with the neoclassical taste, which would then be the final one. The dome was also subject to some changes and, as was customary in those years, was slightly raised. However, the construction work was not to be completed so quickly and it took a little less than a century before the great dome designed by Luigi Cagnola and erected by Rodolfo Vantini was also realized in 1825 , which from the beginning was the driving force and common element of all Drafts was. The various elements of the stucco and marble decor designed by Giovanni Battista Carboni at the end of the 18th century were placed on the inside of the still incomplete dome. The facade, which underwent many changes, was not even fully completed in the end as it dispensed with the balustrade crown that should have been placed along the eaves line of the roof.

The cathedral was seriously damaged when the city was bombed on July 13, 1944. The dome with the lead cladding caught fire and the tympanum , frame and window of the drum , lantern and apse were badly damaged. The nicks and damage to the walls at the rear of the building are due to the bombing the Austrians shot from the castle for ten days in 1849. After being restored in the post-war period, it has now regained its original appearance, although the damage to the walls of the apse is still there.

description

The new cathedral presents itself in an overall homogeneous and cohesive structure in terms of architecture and decoration. Only the subtle connection between baroque and classicism, inside and above all on the facade, reveals the long construction period of 230 years. The result is a kind of watered-down Baroque classic, a building that started with Baroque and ended with Classicism.

Outside

The facade in Piazza Paolo VI. turns out to be the most characteristic element of the building: it is made of Botticino marble , symmetrical and divided in two, the lower part being wider to accommodate the two side entrances. The upper one, however, has a predominantly decorative character and is much higher than the actual ceiling of the cathedral. The Corinthian order was used everywhere on a classical basis . In the symmetrical axis, at street level, is the large entrance portal with a vaulted pediment that contains the bust of Cardinal Angelo Maria Quirini by Antonio Calegari from 1750. On the upper level there is a tall window that is closed by a triangular pediment.

On the main triangular pediment of the facade is the coat of arms of the city of Brescia (to remember that the cathedrals were owned by the city), above the statues of the Assumption and Saints Peter, Paul, James and John , by Giovanni Battista Carboni, Stefano Citerio and Pier Giuseppe Possenti, from 1792. As already mentioned, the statues of Saints Faustinus and Jovita in the niches of the apse are by Antonio and Carlo Carrso and Saint John the Baptist on the side door in today's Via Querini by Broletto.

Inside

The interior is majestic and solemn and is on a plan of a Greek cross. A single nave surrounds the large center of the building, which is surmounted by the dome. The deep apse in the main axis of symmetry was the means of maintaining the Greek cross shape without contradicting the rules of the Counter-Reformation. The Corinthian order of the facade is repeated inside and consistently decorates all walls and pillars of the dome. The latter rests on a tall drum, which is illuminated by large rectangular windows, and the entire structure rests on four columns, which are broken up by eight high free columns, also Corinthian order, and facing the central room. The height from the floor to the top of the lantern is 80 meters. It is the third largest dome in Italy according to its size. The four pendentives are decorated with marble busts of the Evangelists : John and Luke from Santo Calegari il Giovane, while Mark and Matthew are from Carboni. The numerous lower arches, including that of the dome, are decorated with cassettes with marble rosettes, but some are replicas from the post-war period. The entire interior is pervaded by a light blue and white light that comes from stucco and white marble. There are many marble elements, not everything is made of simple stucco: The rosettes of the lower arches and the evangelists in the pendentives of the dome, but also all the architectural elements of the church, are made of marble. H. Columns, pilaster strips, the frieze, window frames and decorations in the lunettes above the side altars.

Works

There are eight side chapels in the cathedral that contain many works of art, especially from the nearby old cathedral:

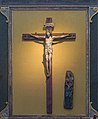

- The first right altar is dedicated to the Holy Cross and houses the crucifix of the New Cathedral by Francesco Giolfino from 1502.

- The Chapel of the Holy Sacrament, the second on the right and thus the chapel on the back of the horizontal arm of the Greek cross, with a classical altar designed by Rodolfo Vantini and the altarpiece Sacrifice of Isaac by Alessandro Moretto ; front left the statue of Faith by Giovanni Seleroni and right the hope by Giovanni Antonio Emanueli . Above the confessional there is a large painting with the venerable Annunciata Cocchetti by Gabriele Saleri from 1990.

- The third altar on the right consists only of a wall fresco painted in perspective and contains the monumental sarcophagus of Saint Apollonius, decorated with refined bas-reliefs and a remarkable example of the Bresk Renaissance sculpture attributed to Gasparo Cairano to whom it was built between 1508 and created in 1510. The sarcophagus was originally located in the Basilica of San Pietro de Dom, but was moved to the old cathedral when the new cathedral was built and from there to the new cathedral. Incidentally, this chapel is the only one that was completely decorated and designed according to the original design of the cathedral. In front of the sarcophagus is an urn made of decorated glass and other materials containing the relic of Saint Benedict of Nursia , designed by Graziano Ferriani.

- On the altar at the end of the right aisle, decorated with Faith and Humility by Antonio Calegari , there is a 19th-century Guardian Angel painting by Luigi Basiletti.

- On the side walls of the choir are the statues of Saint Gaudenzio and Saint Filastrio by Antonio Calegari, while the altarpiece of the high altar shows the Assumption of Giacomo Zoboli.

- The altar at the end of the left aisle contains the Assumption of Saints Charles and Francis and Bishop Marino Giorgi by Jacopo Palma the Younger and is also the tomb of Bishop Giorgi. In this case, the altar itself is also very significant: The work by Lorenzo Binago from the early 17th century looks very traditional, but is in fact the first altar ever with such a scheme and thus represents the prototype of all side altars that produced in Brescia and practically all of northern Italy since the beginning of the 17th century, practically the prototype of the Lombard side altar.

- The third altar on the left is dedicated to Nicholas of Tolentino , is decorated with trompe l'oeil and contains a painting with Saints Nicholas of Tolentino, Faustinus and Jovita in prayer, a work by Giuseppe Nuvolone from 1679.

- On the left back wall of the central arm of the Greek cross is the monument to Paul VI. , a 1984 work by Raffaele Scorzelli. At the foot of the monument is the tombstone of Bishop Luigi Morstabilini, while on the right side, in a monstrance, there is a relic of the Apostle Andrew , which the Pope gave to his hometown. Four organ doors from the Rotonda (old cathedral), the work of Romanino , hang above the monument, depicting the Marriage of the Virgin, the Birth of the Virgin and the Visitation.

- In the first chapel on the right is the baptistery with a bronze statue of St. John the Baptist by Claudio Botta.

- In front of the entrance to the sacristy, to the right of the presbytery, is Saint Anthony of Padua by Giuseppe Nuvolone.

- The tomb of Bishop Ferrari on the left pillar of the entrance is by Giovanni Antonio Emanueli , while that of Bishop Nava on the right pillar is by Gaetano Matteo Monti.

In a room next to the cathedral is a valuable blessing Christ from the first half of the 16th century, which is ascribed to a member of the piazza.

organ

There are two impressive organs in the cathedral: the Mascioni Opus 898 (1968) and the Tonoli-Porro (1855), which are housed in the choir on the gospel side and on the epistle side , both in classicist style.

Tonoli Porro organ

The Tonoli organ was built with a manual in 1855 (the second was added in 1880) to replace an earlier organ from 1750. The instrument was renewed in 1906 by Diego Porro and cleaned by Gianluca Chiminelli in 2005-2006.

Mascioni organ

The Mascioni opus 898 organ was built in 1968 and restored by the same company in 2005.

The instrument with electric action has the pipes between the organ body on the gospel side (positive, expressive, pedal and large organ) and the expressive case behind the old baroque high altar (expressive choir); the console, on the other hand, is located in the presbytery and has three keyboards with 61 notes each and a pedal with 32 notes.

gallery

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Francesco de Leonardis, pp. 114–116

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Panazza, Boselli

- ^ Comune di Brescia - Portale istituzionale del turismo ( it ) turismobrescia.it.

- ^ Louise Colet: L'Italie des italiens . Ed .: E. Dentu. tape 1 . Paris 1862, p. 341 (French): «[…] The new cathedral made of white marble stands next to the old one; its dome is the largest in Italy after that of St. Peter of Rome. [...] »

- ^ Karl-August Wirth: Epistle and Gospel page . In: Real Lexicon on German Art History . tape V , 1962, p. 869-872 .

- ↑ Fonte, da Organibresciani.it ( it ) Archived from the original on November 17, 2015.

literature

- Francesco de Leonardis: Guida di Brescia . Grafo Edizioni, Brescia 2008, p. 114-116 (Italian).

- Gaetano Panazza, Camillo Boselli: Progetti per una cattedrale - La fabbrica del Duomo Nuovo di Brescia nei secoli XVII-XVIII . Brescia 1974 (Italian).

Web links

|

Further content in the sister projects of Wikipedia:

|

||

|

|

Commons | - multimedia content |

|

|

Wikibooks | - Textbooks and non-fiction books |

- L'organo Mascioni ( it )

- Chiesa di Santa Maria Assunta e Santi Pietro e Paolo (Brescia) ( it ) BeWeB - Beni ecclesiastici in web.

- The new and old cathedral . bresciatourism.it.