Battle of Giglio

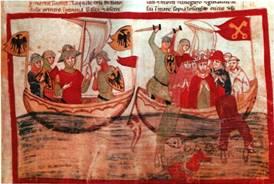

Depiction of the sea battle of Giglio from the Nuova Cronica by Giovanni Villani , early 14th century.

| date | May 3, 1241 |

|---|---|

| place | between Montecristo and Giglio |

| output | Imperial victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Papal side: Genoa |

|

| Commander | |

|

Giacobo Malocello |

Ansaldo de Mari |

| Troop strength | |

| 32 armed galleys | 27 Sicilian galleys 40 Pisan ships |

| losses | |

|

3 galleys sunk |

not known |

The sea battle of Giglio was a military clash between a fleet of the Roman-German Emperor Frederick II and a fleet of the Maritime Republic of Genoa in the Tyrrhenian Sea . It took place on Friday, May 3rd, 1241 between the islands of Montecristo and Giglio ( Tuscan Archipelago ) and ended with a victory for the imperial fleet.

The attack of the imperial fleet on that of the Genoese aimed at the capture of a tour company of high-ranking ecclesiastical dignitaries who were on the way to a council convened by the Pope in Rome .

background

In the spring of 1239 was between Pope Gregory IX. and Emperor Friedrich II. an open conflict broke out on the question of the imperial claim to rule over the cities of the Lombard League, which culminated in the emperor's second excommunication on March 20, 1239. From then on, both sides do not compromise had contributed to the conflict militarily against each other, whereby the emperor, especially in the Papal States reached some successes, which are increasingly threatened the position of the Pope. In the autumn of 1240, the Pope invited the church princes of Italy, Sicily, Germany, France and Spain to a council that was supposed to deal with the further action of the church against the emperor at Easter 1241 in Rome . In his capacity as King of Sicily, Frederick II could easily prevent the participation of the Sicilian prelates, but the clergy of the other countries found themselves in northern Italy in the following months to travel on to Rome, which the emperor tried to prevent.

The fight

Since the emperor controlled the land route through what is now central Italy and thus cut Rome off from northern Italy, the council travelers gathered in Nice , where they were initially transported to its port by a fleet of the Ligurian Maritime Republic of Genoa , which was led by a papal government. The two cardinal legates and informal leaders of the council travelers, Jacob of Palestrina and Otto of San Nicola , negotiated with Genoa the position of 32 armed galleys for the further transport by ship to Rome and as soon as the embassies of the Lombard cities had embarked, the journey was to begin . When Frederick II found out about this plan, in March 1241 he ordered his vicars, Marino di Ebulo and Oberto Pallavicini, who were in power in Lombardy, to attack Genoa from land. Their campaign of devastation in the region around the republic had no lasting effect, however, whereupon the emperor had his Sicilian fleet upgraded to put the Genoese under pressure from the sea. He sent 27 ships with his son Enzio , under the command of Admiral Ansaldo de Mari, to the Maritime Republic of Pisa , Genoa's arch rival and therefore his natural ally.

On April 25, the Genoese fleet solemnly set sail in their hometown, but first headed for the nearby Portofino , where they anchored for a day or two. When the ship's crew there heard of Pallavicini's attack on the republic-owned Zolasco, they intended to come to the city's aid, but the two cardinal legates stopped them by successfully pressing for a quick onward journey to Rome. During another stopover in Porto Venere , they learned of the union of the Sicilian fleet with that of Pisa in their port. Although they now had an opponent between them and their goal, the Genoese decided to set sail again towards Rome with an unknown course, without waiting for seven galleys to be reinforced from Genoa. They managed to pass Pisa, but not unnoticed by the enemy, as he was able to intercept them between the islands of Montecristo and Giglio.

In the pirate fight that followed, the imperial fleet proved superior to the Genoese. Above all, the numerous passengers and their overflowing luggage hindered the Genoese in the adequate defense of their ships, which therefore could only offer weak resistance to avoid the threatening sinking. The imperial succeeded in capturing 22 galleys and capturing their crews and especially their passengers. The traditions regarding three sunk ships are contradictory. In their report, later written for the Pope, the Genoese claimed that they sank three Imperial ships. The other side, in turn, recorded three sunk Genoese ships for themselves, which is also more likely. Ultimately, only 7 Genoese ships were able to escape to their hometown, including the Admiral's ship.

consequences

The capture of the Genoese fleet was a complete success for Emperor Friedrich II. Almost all high dignitaries of the council travelers were taken prisoner. These included the two cardinal legates and another legate. The archbishops of Rouen , Bordeaux and Auch , the bishops of Carcassonne , Agde , Nîmes , Tortona , Asti and Pavia , the abbots of Cîteaux , Clairvaux , Cluny , Fécamp , Mercy-Dieu and Foix, furthermore the diplomatic envoys from England , Milan , Brescia , Piacenza , Genoa and Bologna . They were first taken to Pisa and San Miniato , and later to Naples . The ships that were able to save themselves and thus escape captivity were mainly the prelates from the Iberian peninsula . These included the archbishops of Santiago de Compostela , Braga , Tarragona and Arles , the bishops of Salamanca , Astorga , Porto , Orense and Plasencia . The only Council traveler who died that day was the Archbishop of Besançon (Gottfried), who had gone overboard in the fray and drowned in the sea. Emperor Frederick II saw his victory as a divine judgment that revealed the illegality of his persecution by the Pope. Although the emperor was able to prevent the convening of the council by means of this act of violence, he thereby contributed to the hardening of mutual positions.

It was only the surprisingly quick death of Pope Gregory IX. in August 1241 the situation initially seemed to ease. As a sign of his courtesy, the emperor released the two cardinal legates again in August 1242 and May 1243 in order to clear the way for the election of a new Pope. The newly elected Innocent IV , however, turned out to be just as unyielding as his predecessor. In 1244 he took his exile in safe Lyon , where this time the convocation of a council ( First Council of Lyon ) succeeded, which formally deposed the emperor.

swell

- Matthäus Paris , Chronica Majora , ed. by Henry R. Luard in Rolls Series 57.3 (1876), p. 325; Letter from Emperor Friedrich II to his brother-in-law King Heinrich III. of England with his report on naval combat

- Matthäus Paris, Historia Anglorum , ed. by John Allen Giles (1852-1854), Vol. I, pp. 352-355

- Richard von San Germano , Ryccardi de Sancto Germano notarii Chronica , ed. by Georg Heinrich Pertz in: Monumenta Germaniae Historica (MGH) SS 19 (1866), p. 380

- Annales Ianuae , ed. by Georg Heinrich Pertz in: MGH SS 18 (1863), pp. 194–196

- Annales Senenses , ed. by Georg Heinrich Pertz in: MGH SS 19 (1866), p. 229f.

- Annales S. Pantaleonis , ed. by Georg Waitz in: MGH SS rer. Germ. 18 (1880), p. 279

- JLA Huillard-Bréholles , Historia Diplomatica Friderici Secundi (1852–1861), Vol. V, pp. 1108, 1120, 1124f., 1127, 1146

literature

- Wolfgang Stürner : Friedrich II. 1194-1250 . 3rd edition, bibliographically completely updated and expanded to include a foreword and documentation with additional information, in one volume. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-534-23040-2 , p. 501

Remarks

- ↑ In a secret letter dated March 25, 1241, the emperor informed the party in Genoa, who were sympathetic to him, of the forthcoming activities against Genoa. Huillard-Bréholles, p. 1108

- ↑ On the report of the Genoese to the Pope see Odoricus Raynaldus, Annales ecclesiastici from anno 1198 (1646–1677), § 1x

- ↑ Huillard-Bréholles, pp. 1124f., 1127, 1146

- ↑ The names of the prisoners were given by the Archbishops of Tarragona and Arles in a letter to the Pope on May 10, 1241. Huillard-Bréholles, p. 1120