Skylab

| Skylab | |

|---|---|

| Mission emblem | |

| Mission dates | |

| Mission: | Skylab 1 |

| Crew: | (three crews of three astronauts each) |

| Start on: | May 14, 1973 |

| Re-entry on: | July 11, 1979 |

| Duration: | 6 years, 58 days |

| burns up over: | Australia |

| Earth orbits: | 34,981 |

|

previous mission : |

following mission : |

Skylab was the first and so far only purely US space station and the name for the space missions in this context. During the eight months between 1973 and 1974, a total of nine astronauts worked on the Skylab, in three teams of three men each.

planning

While the Apollo program was being prepared , NASA was already considering the future of manned space travel . To this end, the Saturn / Apollo Applications Office was founded in August 1965 . This had the task of looking for possible uses for the Apollo developments and infrastructure. The aim was to preserve the knowledge gained by the engineers who would otherwise have been dismissed after the end of the Apollo program. Proposals were taken up very early on to convert an upper stage of a Saturn launcher into a space station and to use previously unused Apollo spaceships and Saturn IB to transport personnel.

NASA had been looking for new astronauts in advance. This time it wasn't test pilots who were asked, but scientists. On June 28, 1965, Owen Garriott , Edward Gibson , Duane E. Graveline , Joseph Kerwin , Frank C. Michel, and Harrison Schmitt were introduced to the public as science astronauts .

Many proposals were made based on Saturn rockets and Apollo spaceships . However, the only Apollo Application Program project that came to fruition was a three-man orbiting space station . Originally it was planned to start this with a Saturn IB and to expand the burned-out S-IVB upper stage into a space station in several flights (concept “wet workshop”). However, it turned out that this concept was too costly. In the summer of 1969 they switched to the plan to assemble the space station on the ground and start it with a Saturn V, in which only the two lower stages contributed to the propulsion (“dry workshop”). The SA-513 rocket, which was previously intended for Apollo 18 , was used for this. The Apollo 20 mission was deleted from the lunar program in January 1970 because Saturn V was no longer available. From February 1970 the name Skylab was officially used for the space station .

The McDonnell Douglas company manufactured two copies of the space station in 1970. One was used for training, the other was the aircraft. There were considerations to bring the training model into space as Skylab B , but this was discarded for financial reasons.

Building Skylab

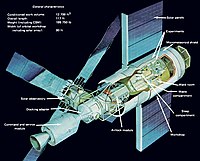

The Skylab consisted mainly of the second stage of the Saturn IB AS-212 (identical to the third stage of a Saturn V ), which was already provided with supplies and equipment on Earth. So only two stages of a Saturn V were used for the start. This was the first and at the same time the last launch of a Saturn V in this configuration, as this type of rocket had previously only been used for Apollo spacecraft . This part of the station was the Orbital Workshop (OWS). It weighed 35.8 tons. The crew lived and worked in the hydrogen tank with a usable internal volume of 275 m³. The oxygen tank was equipped with a lock and used as a waste pit. The OWS housed the equipment, all food supplies, all water supplies and the pressure tanks for the fuel for position control. In addition to the living rooms, bedrooms and sanitary rooms, experiments were also carried out there, especially earth observation through a window and medical examinations. The OWS had two small locks for experiments on the side of the station towards and away from the sun; the former was permanently documented for the repair of the thermal protection. The habitable volume was divided several times into dining and relaxation areas as well as individual sleeping cabins, especially with grid-like floors that the astronauts could hook themselves into with special shoes. Due to the large diameter, a volume of 280 m³ was habitable. This volume was only exceeded by the Mir in its final expansion stage.

It should be noted that Skylab did not have the (simple) possibility of refilling (by refueling or similar), which is essential for a space station according to later understanding. However, some of the resources could have been supplemented, at least in the context of an external mission, using the valves also used on earth.

The OWS was followed by the instrument ring of the Saturn V, which was retained in order to avoid changes to the launch systems. He steered the launcher and after takeoff, when Skylab was in orbit, gave control to Skylab's internal computers. The OWS was followed by the 22 t airlock, the Airlock Module (AM). It contained an airlock to exit, locked the OWS from the docking adapter, contained the control of the telescopes and all gases for the station in pressure tanks. Their width decreased from 6.7 to 3.04 m. It had a length of 5.2 m and an internal volume of 17.4 m³.

This was followed by the cylindrical multiple docking adapter (MDA). It was 3.04 m wide, 5.2 m long and had a mass of 6260 kg. It had two docking points for Apollo command capsules: one radial and one in the extension of the longitudinal axis. The radial docking point was intended for an emergency capsule that was to be launched when a return with the first capsule would not have been possible, but was functionally equivalent to the axial one.

For solar observation, which was an important goal of Skylab, the space station also had an observatory, the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM), which was extended to a sideways position on the MDA after reaching orbit. It weighed 11,066 kg, was 6 m wide and 4.4 m high. Its solar telescopes could be aligned with an accuracy of 2.5 arc seconds. It was controlled from the OWS, whereby the films had to be changed as part of an outboard maneuver (EVA). The energy supply was planned with four solar modules on the ATM and two more on the main module. The ATM's solar panels alone had a span of 31 m. The ATM used components from the lunar module and aligned the entire station with its spin wheels .

Finally there was the attached Apollo spacecraft as a Command and Service Module (CSM). The CSM took over all communications with Earth, as Skylab, apart from its on-board telemetry, did not have its own transmitter. Furthermore, the life support systems of the CSM had to take over the gas cleaning once a month when the molecular sieves were baked out by Skylab . The CSM was therefore an integral part of the station.

The mass of the station was over 90 tons. Overall, Skylab was much larger than the Soviet Salyut 1 space station , which was launched in April 1971. When the sun was in a favorable position, the Skylab could be seen with the naked eye as a shining point in the daytime sky.

Start of Skylab 1 and damage analysis

The launch of Skylab (mission name Skylab 1) was scheduled on May 14, 1973 from launch complex 39-A in Cape Canaveral . The Saturn V SA-513 used for Skylab 1 was slightly shorter than the models used for the moon flights. It had no rescue rocket , no Apollo spacecraft, and no adapter for the lunar module . In addition, this missile used only two stages. In place of the third stage, it transported the space station with a cone-shaped fairing on top. Like the later Apollo Soyuz project , the launch took place from a launch pad that was shortened by means of an attachment. This flight was the last of a Saturn V. The orbit was chosen with an inclination of 50 ° so that large parts of the earth's land areas were flown over.

Just 63 seconds after take-off, the ground station received alarming telemetry signals. When the sound barrier was breached , the entire micrometeorite protective shield tore off within just three seconds, which also damaged two solar module carriers. Later investigations showed that the error was caused by a lack of coordination between the design departments (see Not-Invented-Here-Syndrome ). The space station reached the planned orbit but was not functional. The flight control managed to extend the four solar modules of the solar observatory, but there seemed to be problems with the other two modules, so that only about half the electrical power was available. The missing meteorite shield should also have served as thermal protection, which is why the temperature in the station rose sharply, so that it had to be feared that food, medicines and films would be spoiled.

The next day, on May 15, 1973, the first crew (mission name Skylab 2 ) with a Saturn IB was to follow from launch pad 39-B. It was the first time that two Saturn rockets had prepared the countdown at the same time. Something similar had happened in December 1965, when Gemini 7 and Gemini 6 were launched one after the other. As a first reaction to the damage that occurred during take-off and the resulting uninhabitability of Skylab, the take-off was postponed twice by five days each time until one could get a clear picture of the situation. In addition, the flight control tried to achieve a favorable alignment of Skylab. If the functional solar cells were facing the sun, enough energy could be obtained, but at the same time the station heated up strongly. If you turned the station so that the place with the missing protective shield was in the shade, the solar cells also gave too little power and the charge level of the batteries fell. NASA engineers now had the problem of keeping energy reserves, fuel reserves and the temperature of the space station within reasonable limits. If it were not possible to repair the damage within days, the station would be lost. The station was controlled in this way for two weeks while the Skylab-2 mission was being prepared. Repair plans were drawn up and tools developed, including a cutting device based on commercial pruning shears and tin shears with extensions, as well as rods and cables. To simulate weightlessness , the Skylab 2 team practiced the necessary steps in a water tank.

The teams managed to repair the damage during the Skylab 2 and Skylab 3 missions . The station was then fully functional. More about the repair work (eng .: On-Orbit Servicing ) in the corresponding articles.

Mission objectives and crews

The crew's tasks initially included repairing the damaged space station. In contrast to the Apollo program, which had clearly aimed at landing on the moon, the goals of Skylab were rather vague in advance. The mission goals can be summarized as follows: solar observation via the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM) and earth observation as well as knowledge gain in the areas of spatial physics, materials research and biomedicine.

Three crews of three astronauts each spent a total of 513 man-days in space. Since the launch of Skylab was counted as Mission 1, the manned missions begin with number 2:

-

Skylab 2 :

- May 25, 1973 - June 22, 1973

- Crew: Charles Conrad , Paul J. Weitz , Dr. Joseph P. Kerwin

-

Skylab 3 :

- July 28, 1973 - September 25, 1973

- Crew: Alan L. Bean , Dr. Owen K. Garriott , Jack R. Lousma

-

Skylab 4 :

- November 16, 1973 - February 8, 1974

- Crew: Gerald P. Carr , Dr. Edward G. Gibson , William R. Pogue

During the operation of Skylab, an emergency team was kept on standby, which the primary team could have saved ( Skylab rescue plan ). An Apollo capsule with two additional seats under the original and another Saturn IB was available for this. It was planned that Vance Brand and Don Lind would fly to Skylab in pairs and bring their comrades back. This mission was never carried out, but both astronauts came on later missions.

Compilation of the results

In total, around 25% of the total man-hours worked on Skylab were used for scientific experiments. In addition to the results mentioned below, comet C / 1973 E1 (Kohoutek) could also be observed.

Solar observations

The solar telescope cameras on board were able to take over 177,000 pictures. For the first time it was possible to observe the sun over a longer period of time without the influence of the earth's atmosphere. This enabled new knowledge to be gained about the behavior of the corona and the chromosphere .

Earth observations

For studies on the mapping of saline soil, crop stands, ecosystems and mineral deposits, more than 46,000 images were taken from the six earth sensors (1 × photography in the visible range, 1 × photography in the infrared range, 2 × electronic image recorders in the infrared range, 2 × radar devices for observation in the microwave range ) made. The last two radars mentioned - the first ever to be used in space - led to trend-setting results on the wind speed over the ocean, swell and wave height, the localization of icebergs and ice floes as well as the mapping of geological formations on the mainland.

Biomedicine

Extensive knowledge could be gained about the effects of long-term stay in weightlessness . It turned out that the consumption of resources was significantly lower than assumed. The crew lived on the supplies and food, water and gases launched with Skylab 1. Originally, the second and third crew should each stay in the space station for 56 days. However, the lower consumption made a stay of 59 and 84 days possible, with the last crew adding up the supplies a little and in particular bringing additional films with them.

In addition, some animal experiments were carried out with fish and spiders.

Materials research

Experiments with melting, welding and brazing processes were carried out in weightlessness, which demonstrated the possibility of astronauts building technical structures in space. Furthermore, the miscibility of immiscible elements of different densities on earth was proven in weightlessness and crystal growth experiments that failed on earth due to the acceleration of gravity could also be carried out successfully.

End phase of the space station and crash

After three crews had inhabited the space station for 28, 59 and 84 days, it was pushed into higher orbit on February 8, 1974 by the Apollo spacecraft from Skylab 4 . About a third of the original water supply of 2720 l (corresponding to about 180 man-days), oxygen for about 420 man-days and similar supplies of almost all other consumables remained on board. According to NASA calculations , Skylab should remain usable for about nine more years after the orbit lift. The re-entry into the earth's atmosphere was estimated to be March 1983. At that time it was still planned that around 1979 a space shuttle could couple a drive module to Skylab in order to bring the space laboratory back into a higher orbit. This should be done with the canceled mission STS-2a . However, there were no specific plans for the further use of the station, which would have been problematic due to the old technology.

Most of the space station's systems were shut down (such as the telemetry transmitter on February 9, 1974 at 2:10 AM EST). Skylab orbited the earth for several years without paying any attention. In March 1978, contact with Skylab was resumed. Apparently the station rotated largely uncontrollably with a period of six minutes per revolution, and the radios only worked when the solar panels were in the sunlight. After a week it was possible to charge several batteries remotely. The central computer was still working satisfactorily, but the position control was considerably impaired by the failure of a star sensor and the partial failure of one of the three spin wheels .

However, it turned out that Skylab was sinking faster than calculated. The reason for this was the unexpectedly expanded high atmosphere of the earth due to high solar activity and the increased deceleration that resulted. Furthermore, it was known at this point that the space shuttle would not be ready in time. An alternative mission - for example with a Titan III as a carrier - was discarded. On December 19, 1978, NASA announced that Skylab could not be saved, but that everything was being done to minimize the risk of crash damage. To this end, NASA worked closely with the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD). NASA and NORAD used different calculation methods for reentry and therefore came up with different results for the time and place of the decline. Officially, however, the NORAD results were always announced.

NASA planned to control the atmospheric friction by orienting the space station in order to decelerate or accelerate the crash. By remote control, Skylab should then be set in rotation with known aerodynamics at a certain point in time. This enabled the danger zone to be relocated within narrow limits.

The crash then took place on July 11, 1979. The last orbit of Skylab was mostly over water, and NASA gave the final control command to shift the danger zone away from North America to the Atlantic and Indian Oceans . In fact, the station broke into several parts later than calculated, so that the crash area was further east than planned. Affected was the area southeast of Perth in Western Australia near Balladonia , where debris fell in the dark hours of the morning without injuring anyone. Various parts were recovered, brought to the United States and identified there after NASA offered a reward for the first find. The authorities in the Australian community of Esperance Shire sent NASA a $ 400 fine for unauthorized waste disposal. NASA refused payment; It was not until 2009 that the nominal amount, which had actually already been written off, was paid by a US radio station.

The entire mission cost about $ 2.6 billion.

See also

literature

- Bernd Leitenberger: Skylab: America's only space station , Space Travel Edition, Norderstedt 2016, ISBN 978-3-8423-3853-1

The following NASA books (all in English) are available online:

- Skylab, Our First Space Station

- Living and Working in Space: A History of Skylab

- Skylab's Astronomy and Space Sciences

- A New Sun: The Solar Results from Skylab

- Skylab, Classroom in Space (describes the 25 science experiments designed by students)

Also on the NASA History Office website:

- LIVING AND WORKING IN SPACE, A HISTORY OF SKYLAB

- Skylab: A Chronology

- Skylab: A Guidebook

- NASA Investigation Board Report on the Initial Flight Anomalies of Skylab 1

Web links

- extrasolar-planets.com - Skylab (German)

- The American space station Skylab (Ger.)

- Skylab in the Encyclopedia Astronautica (English)

- Skylab in the NSSDCA Master Catalog (English)

- NASA photos of the Skylab

- Skylab website by Bernd Leitenberger

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Jesco von Puttkamer: "Skylab" space station - the harvest begins. VDI-Z Volume 116 (1974) No. 16, pp. 1283-1291

- ^ Richard D. Lyons: Skylab Debris Hits Sea and Australia; No Harm Reported. New York Times, July 12, 1979; accessed December 24, 2009.

- ^ Hannah Siemer: Littering fine paid. (No longer available online.) The Esperance Express April 17, 2009, archived from the original on January 24, 2011 ; accessed on September 23, 2011 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Ian O'Neill: Celebrating July 13, "Skylab-Esperance Day". Discovery News, July 14, 2009, accessed September 24, 2011 .