Apollo 13

| Mission emblem | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Mission dates | |||

| Mission: | Apollo 13 | ||

| COSPAR-ID : | 1970-029A | ||

| Command module: | CM-109 | ||

| Service module: | SM-109 | ||

| Lunar Module: | LM-7 | ||

| Launcher: |

Saturn V , serial number SA-508 |

||

| Call sign: | CM: Odyssey LM: Aquarius |

||

| Crew: | 3 | ||

| Begin: | April 11, 1970, 19:13:00 UT JD : 2440688.3006944 |

||

| Starting place: | Kennedy Space Center , LC-39A | ||

| Lunar orbits: | 0.5 (moon circled but not circled) | ||

| Landing: | April 17, 1970, 18:07:41 UT JD : 2440694.2553356 |

||

| Landing place: |

Pacific 21 ° 38 ′ S , 165 ° 22 ′ W |

||

| Flight duration: | 5d 22h 54m 41s | ||

| Recovery ship: | USS Iwo Jima | ||

| Team photo | |||

Apollo 13 - v. l. No. Jim Lovell , Jack Swigert , Fred Haise |

|||

| ◄ Before / After ► | |||

|

|||

Apollo 13 was the seventh manned space mission in the Apollo program of the US space agency NASA with the aim of the third manned moon landing . After the explosion of a tank with supercritical oxygen in the service module of the Apollo spacecraft , landing on the moon was no longer possible, and the three astronauts Jim Lovell , Jack Swigert and Fred Haise had to return to Earth as part of a rescue operation that received worldwide attention .

Summary

On April 11, 1970, a Saturday, the Saturn V rocket took off at 19:13:00 UT from Launch Complex 39A of the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. About 56 hours later - still on the way to the moon - the accident happened. In order to survive, the astronauts transferred to the lunar module , where they spent most of the time until shortly before re-entering the earth's atmosphere . After the tank exploded, almost 88 hours passed, which were only survived with several technical improvisations, until the command module with the three men on Friday, April 17, 1970 near the salvage ship USS Iwo Jima at 18:07:41 UT South Pacific watered down .

crew

Main crew

On August 6, 1969, shortly after the first successful manned moon landing by Apollo 11 , NASA announced the crews for the Apollo 13 and Apollo 14 missions .

James A. "Jim" Lovell was appointed commander of Apollo 13 . Lovell undertook a fourth space flight after Gemini 7 , Gemini 12 and Apollo 8 as the first space traveler. At the same time, he became the first person to undertake a second Apollo mission and the first person to fly to the moon twice; However, he never entered it.

Pilot of the Apollo Command Module should first Thomas "Ken" Mattingly are, as a pilot of the lunar module was Fred W. "Freddo" Haise provided. The two were the first of the fifth astronaut selection group to be assigned to the main crew for a space flight.

A few days before take-off, on April 6, 1970, the lunar module's replacement pilot, Charles Duke , fell ill with rubella . It turned out that Ken Mattingly wasn't immune to it. To eliminate the risk of Mattingly falling ill while on the moon flight, he was replaced on April 9 by reserve pilot John L. "Jack" Swigert . Later he took part in the Apollo 16 mission for which Swigert was actually intended. It was found later that Mattingly had not contracted rubella.

Ground control, replacement and support

John Young was assigned as the commandant of the reserve team. Swigert became a replacement pilot for the Apollo command module; Charles Duke took over the role of substitute pilot for the lunar module. After Duke fell ill, Swigert was briefly appointed to the main crew. Mattingly took over his post on the substitute team.

The support crew consisted of Jack R. Lousma , William R. Pogue and Vance D. Brand . All three already had experience as a support crew or liaison spokesman ( Capcom ).

The flight management from the control center in Houston should be done in a four-shift system. A flight director was assigned to each shift, who had his own team of system specialists, which he shared with him.

The flight controllers scheduled for Apollo 13 were (in the order of their shifts): Milt Windler, Gerald Griffin, Gene Kranz (head of the flight control team at the time - lead flight director) and Glynn Lunney.

After the accident, the planned shift system was deviated from. Kranz's team was pulled out for crisis management and only took over direct control for particularly critical flight phases, while the other flight controllers now took turns in a three-shift system.

Joseph P. Kerwin , Vance D.Brand, Jack Lousma and Charles Duke served as fixed liaison speakers (Capcom) . The Capcoms also worked in a shift system, which, however, in order to avoid a simultaneous exchange of the control team and the Capcom, was not congruent with the shift system of the flight controllers. In the short-term absence of the Capcom, other astronauts present in the control center could take over this function. Likewise, could Tom Stafford as head of the Astronaut Office and Deke Slayton always turn in communication with the spacecraft as chief astronaut.

Team rotations

The Apollo crews were not put together just before the crews were announced, but they had worked together for years. Usually, a crew was initially assigned as a substitute team to form the main crew three missions later.

Jim Lovell as commander, William Anders as pilot of the command module and Fred Haise as pilot of the lunar module had formed the replacement crew for Apollo 11 . This crew would have become the main crew of Apollo 14 according to schedule . After Apollo 11, Anders left NASA and was replaced by Mattingly. The Apollo 10 backup crew consisted of Gordon Cooper (commander), Donn Eisele (pilot of the command module) and Edgar Mitchell (pilot of the lander). This crew was disbanded after Apollo 10 and reformed under the command of Alan Shepard , with Stuart Roosa as pilot of the command module and Mitchell as pilot of the lunar module. Shepard had recently been cured of Menière's disease by surgery and had been written to be able to fly again. NASA management was concerned about entrusting him with the Apollo 13 mission after such a short preparation time, but recommended that Jim Lovell's crew be given preference for Apollo 13 instead. Shepard's crew was then assigned to Apollo 14.

Unlike when the crews of Apollo 8 and Apollo 9 were swapped, in this case the replacement crews were not swapped.

preparation

The individual stages of the Saturn V rocket AS-508 were delivered to Cape Kennedy in June and July 1969 and assembled in the Vehicle Assembly Building . On December 15, 1969, the rocket was rolled to launch pad 39A. The Apollo spaceship CSM-109 was given after the epic of Homer the name Odyssey , the Lunar Module LM-7 after the constellation called Aquarius .

Like the Apollo 11 crew , the Apollo 13 astronauts did not want their names to appear on the mission badge. Instead, it received the Latin motto Ex Luna, Scientia ("Knowledge [comes] from the moon") . So there was no need to change the logo when the pilot Mattingly was replaced by Swigert a few days before take-off. Some new team photos were of course still taken.

Most of the remaining two days, the astronauts spent in the simulator to coordinate their actions.

The plan was to land on the moon in the Fra Mauro highlands . This was the first landing site as part of the Apollo program that was not in one of the relatively flat seas ( marine areas ) of the moon. The landing site promised a diverse spectrum of rock shapes; in particular, with the help of the rock finds it should be possible to date the great asteroid impact that formed the Mare Imbrium . Fra Mauro was so important to the scientists that after the failure of Apollo 13, the landing area was also nominated for the successor Apollo 14 mission .

The crew had dealt extensively with geological studies before the flight in order to be able to achieve the highest possible scientific yield during the lunar excursions.

In addition to taking rock samples from the Cone Crater , the ALSEP (Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package) should be set up near the landing site .

Flight history

begin

Apollo 13 launched on April 11, 1970, 19:13:00 GMT from Cape Canaveral , Florida (1:13:00 p.m. from the control center in Houston ). The initial phase of the launch was monitored from the Launch Control Center not far from the launch platform. The engines were ignited about nine seconds before the planned take-off. Four holding arms at the base of the rocket (not to be confused with the service bridges of the launch tower) held the Saturn V in place until the full engine thrust was built up. If an engine had not reached full power, the start could still have been aborted. As soon as the holding arms were withdrawn, they were lifted off. Five seconds after the start, the YAW (yaw) program was initialized, i.e. H. the launcher steered slightly away from the launch tower to avoid colliding with it. After 10 seconds, the Saturn V was released from the launch tower and mission control was handed over to Milt Windler and his team in Houston. A few seconds later the ROLL procedure was initiated, which reduced the rocket's azimuth from 90 ° to 72 ° and resulted in a trajectory that led out to the Atlantic. After just under 3 minutes at a height of 68 km, the first stage was burned out and separated. Due to strong vibrations as a result of a pogo effect , the middle engine of the second stage switched off automatically 132 seconds too early, which the missile's autonomous flight control system compensated by allowing the remaining four engines to burn 34 seconds longer. The third stage also burned 9 seconds longer. Despite the unexpected disturbance, the deviation from the planned orbit was minimal. After one and a half orbit around the earth, the third stage was ignited a second time to set Apollo 13 on its way to the moon.

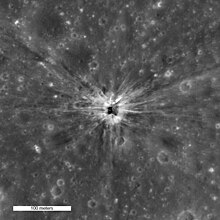

The Saturn impact

One experiment that was hardly noticed against the background of the following events was the Saturn impact (impact of the third rocket stage S-IVB) on the moon. Shortly after disconnecting the command and service module (CSM) and coupling the lunar module (LM), the third stage of the Saturn V was successfully brought on a collision course with the moon by releasing the oxygen and igniting the APS control nozzles. Three days later, the almost 14,000 kg step hit about 120 km west-northwest of the Apollo 12 landing site at 2.5 km / s (9,000 km / h). The impact corresponded to the explosive effect of a good 10 t TNT . After about 30 seconds, the seismometer set up by Apollo 12 registered the impact. The quake lasted more than three hours. Shortly beforehand, the ionospheric detector registered a gas cloud. It was detectable for more than a minute. It is believed that the impact hurled particles from the lunar soil up to a height of 60 kilometers, where they were ionized by sunlight.

The accident

55 hours and 54 minutes after take-off, over 300,000 km from Earth, one of the two tanks with supercritical oxygen in the service module of the “Odyssey” exploded shortly after the fan in the tank was started. Capsuleer Swigert reported over the radio: "Okay Houston, we've had a problem here." “ Okay, Houston, we just had a problem here. "Astronaut Jack R. Lousma , who at the time was Capcom in contact with the crew at the control center in Houston , asked:" Could you please repeat that? "Then Commander Lovell answered and repeated:" Houston, we've had a problem."

According to Fred Haise, the crew's disappointment at the missed moon landing was far greater at first than their worry about how and whether they could return to earth at all.

The explosion of oxygen tank 2 also damaged the pipe system of the tank 1 next to it. The three fuel cells , which were fed with oxygen from the two tanks to generate electricity and water, could therefore only do their work for a few hours. The only option was to abort the mission and bring Apollo 13 back to Earth as quickly as possible, since a further reduction in the supply of oxygen - and thus electrical energy and water - in the "Odyssey" command / service module could not be compensated for.

The lunar module "Aquarius" played the role of the "lifeboat" in which the crew had to stay until shortly before they re- entered the earth's atmosphere . Survival in the damaged command / service module "Odyssey" was only possible for a short period of time. However, these resources had to be saved under all circumstances for the re-entry phase. Before that, the systems of the command module (CM) , including the Primary Guidance, Navigation and Control System with the AGC navigation computer , had to be switched off according to a precisely coordinated scheme in order to be able to reactivate them later for re-entry. At the same time, the systems of the lunar module were activated so that it could take over the tasks of navigation and life support.

Since a direct reversal was ruled out due to the unknown state of the main engine on the service module (SM) , a lunar orbit with a swing-by maneuver had to be performed using the gravitational field . For this purpose, the course was slightly changed by a short burning phase of the lunar module's landing engine, so that the trajectory led back to earth after the orbit around the moon. This maneuver put the spaceship on a free return path ; without the correction, the spaceship would only have approached the earth within approx. 60,000 km.

The CO 2 absorber filters ( lithium hydroxide ) of the "Aquarius" life support system were only designed to bind the carbon dioxide in the air that two people exhale for a maximum of 45 hours. But all three astronauts would stay in the lunar module for over three days. An additional handicap was the square CO 2 filters used in the command module, which were incompatible with the cylindrical filters in the lunar module . A team at the Mission Control Center in Houston developed items on board, such as: B. hoses, adhesive tapes, covers of manuals, etc. a corresponding adapter. The "construction instructions", in which a sock was also used, was then sent to the crew, who then successfully built the adapter for the CO 2 absorber in the lunar module.

While there was enough oxygen on board, there was too little water for cooling and, in particular, electrical energy that came from a silver oxide-zinc battery in the lander. Shortly before the re-entry phase, the silver oxide-zinc batteries in the command module, which had been partially discharged during the accident, had to be recharged from the lunar module using an improvised cable.

In order not to strain the lunar module's scarce reserves to the extreme and to reduce the stress on the crew, the spaceship was accelerated two hours after circling the moon by a four and a half minute burn phase of the lunar module landing engine. This burning phase, known as “PC + 2”, was a maneuver planned in advance for possible emergencies (“PC” stands for “ Pericynthion ”, the point of closest approach to the moon). This shortened the total flight time to 142:40 hours and at the same time ensured that the command module could go down in the Pacific , where the US Navy had stationed a salvage fleet . Since this measure alone would not have been sufficient, most of the electrical systems of the lunar module were switched off and only started up again a few hours before landing. Because the cabin heating also had to be switched off and the waste heat from the electrical consumers was missing, the temperature in the spaceship fell to around 0 ° C during the return flight to Earth.

landing

The normal return reserves of the landing capsule could be used for the last part of the flight . In contrast to a normal mission, the capsule required for re-entry into the earth's atmosphere was only put into operation by the crew shortly before the end of the flight and separated from the Aquarius. Fears that the switched-off electrical system of the command capsule could have been damaged by moisture and frost did not materialize. The supply part burned up like a normal flight in the earth's atmosphere; The lunar module was also lost, in whose landing stage the ALSEP station with its radioisotope generator was still located as power supply. However, no released radioactivity was detected, as this case had been planned in the design of the generator container and it could survive a reentry without damage. Since the radio silence, known as the “ blackout ”, lasted noticeably longer than the usual four minutes on re-entry, this led to the fear that the crew and the landing capsule might be lost. The prolonged blackout resulted from the fact that the entry angle of the capsule was slightly flatter than planned. On April 17, 1970 at 1:07 p.m. , Apollo 13 splashed down without problems in the Pacific southeast of American Samoa . The helicopter 66 brought the crew to the recovery ship USS Iwo Jima (LPH-2) about 6.5 km away .

Whereabouts of the spacecraft

After the rescue, the CM was first dismantled to clear up the accident. The outer shell was exhibited for a while in the Musée de l'air et de l'espace in Paris . Upon completion of the studies, it combined the installed equipment to the training module and put it to 2000 in the Museum of Natural History and Science (Natural History Museum) in Louisville , Kentucky , from. Then the internals were put back into their original shell; the restored command module has since been located in the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center , Hutchinson , Kansas .

Cause of misfortune

The reason for the explosion was not, as is often read, a broken cable in the oxygen tank, but the consequences of a thermostat short-circuited under excessively high voltage as well as a chain of omissions and misjudgments.

The oxygen tanks

The Apollo service module contained two adjacent oxygen tanks that contained cryogenic supercritical oxygen. The oxygen is in a boundary state between liquid and gaseous and is under high pressure. In addition to the filling, draining, extraction and venting lines, some electrically operated devices that were combined in one assembly were required to operate the tank. These were a thermometer, a sensor for the level indicator, a heating element and a fan. The heating element was necessary to maintain the required operating pressure of the tank. The fan was needed to mix the contents of the tank, as cryogenic substances tend to form layers in weightlessness. After assembly, the inside of the tank was no longer accessible for inspections.

The NASA had the construction contract for the service module to the company North American Aviation awarded; in turn, the company had commissioned Beechcraft to build the oxygen tanks. The specification included a. the requirement to protect the heating elements of the tanks with a thermostat switch designed for the on-board voltage of the Apollo spacecraft of 28 V DC.

Failures

In 1965, NASA changed the specifications so that the electrical components of the oxygen tanks were to be designed for the higher voltage of 65 V DC used on the launch pad. Beechcraft forgot to set the thermostat switch from 28 volts for the voltage of 65 volts required on the Cape. Neither Beechcraft nor North American nor NASA noticed this omission. This and all other failures were determined a few months after the accident by the Cortright Commission (see below, section "Significance ...").

The oxygen tank no. 2 used in the service module of Apollo 13 originally belonged to the service module of Apollo 10 , but was removed there for subsequent changes. The tank slipped off the mounting hook and fell about 5 cm, damaging the drain valve unnoticed.

The countdown demonstration test for Apollo 13 took place 2 weeks before the launch date. After this test, the tanks of the spaceship had to be emptied again. This was only partially successful with oxygen tank no. It was assumed that the venting device was damaged in the incident at the manufacturing plant and that some of the oxygen therefore flowed back into the tank. Since the discharge device was no longer necessary during the flight, it was not considered necessary to replace the tank, but instead decided to use an alternative procedure: to let the oxygen evaporate with the help of the tank heater. The heater was on for over 8 hours. The fact that the thermostat switch was not re-dimensioned to the new operating voltage of 65 volts DC caused the thermostat to respond, but the greatly increased amperage of 6 amps meant that its switching contacts welded together and the current flow was therefore no longer interrupted. The resulting high temperature damaged the insulation of the fan supply line. Later tests confirmed this. As a result, the tank and the Teflon coating of the heating rod overheated.

Since the thermometer scale on the start ramp was only designed for a maximum of 27 ° C and it was expected that the thermostat would switch off the heating at this value at the latest, the overheating to over 370 ° C and the resulting consequential damage went unnoticed. The continuously flowing current of the heating element was graphically recorded in the control center, but not noticed.

The explosion

46 hours and 40 minutes after the start, the fan in oxygen tank 2 was routinely activated. There were first signs of a problem when the level indicator rose from its previous normal value to over 100% and remained in this position. To investigate the problem more closely, the floor control had the fan switched on again around an hour later and after three additional hours without the display changing.

When Jack Swigert restarted the ventilator in the oxygen tank at 55:54 hours of flight time at the instruction of the ground control, a short circuit occurred. A fire started in the pure oxygen atmosphere of the tank and it spread rapidly. This increased the tank pressure until the tank finally exploded.

“ Fred annoyed us most of the day by making fun of opening the pressure equalization valve between the 'Odyssey' and the 'Aquarius' over and over again. There was a loud noise that terrified the rest of us every time. I was in the process of checking a couple of systems when Oxygen Tank 2 exploded with a loud bang. At first I thought it was Freddo again, but when I turned around he was sitting far from the valve in his seat. He was pale as death and just shook his head. Then I knew something had happened. "

The pipe system of the neighboring oxygen tank 1 was also damaged by the explosion, so that its contents almost completely escaped during the following 130 minutes. A part of the outer lining of the service module was blown off, which collided with the directional antenna and possibly also damaged the main engine of the service module.

Significance for the Apollo program

Unlike for NASA, moon landings had meanwhile lost their importance for the media and the population, Apollo 13 would have been the third landing in a period of just under 9 months. The US television networks did not broadcast live broadcasts from the spaceship, they were only seen in the Houston control center. It was not until the accident became known that media from all over the world joined in.

Commander Jim Lovell later described the course of the only mission of the Apollo program that had to be prematurely terminated as a "successful failure". Flight director Gene Kranz called it " NASA's finest hour" .

After an internal commission of inquiry led by Edgar Cortright, head of NASA's Langley Research Center , published its report in June 1970, design changes were made to the oxygen tanks of the remaining Apollo service modules. In particular, the thermostat switches were replaced; a third oxygen tank was also installed. In January 1971, the Apollo program continued with the Apollo 14 mission .

On September 2, 1970, the missions planned for 1972/1973 by Apollo 15 (internal designation H-4) and Apollo 19 ( Apollo 20 had already been canceled on January 4) were finally canceled due to budget cuts in the US budget. The remaining four missions have been renumbered 14 through 17. It may have played a role that there was a fear that another (and possibly fatal) disaster could lead to the cancellation of the entire manned space program.

This mission also deserves a record: Also due to the larger radius of the orbit around the moon, the three astronauts of Apollo 13 are the people who were furthest from the earth: 401,056 km at the outermost orbit point around the moon.

Trivia

- The Mission was filmed in 1995 with Tom Hanks , Kevin Bacon , Ed Harris , Gary Sinise and Bill Paxton in the lead roles. The drama was released under the title Apollo 13 and won two Oscars .

- The famous report from the astronauts to Houston was not Houston, we have a problem , as is often reported, but Swigert reported to the ground station: Okay, Houston, we've had a problem here. Lovell then made the same report when asked by CapCom : Houston, we've had a problem . The German translation Houston, we have a problem can still be regarded as correct, since this past tense is (also) used in English for actions that continue into the present or to emphasize the reference to the present.

- Coincidentally, Jack Swigert, of all people, was the astronaut on board Apollo 13 who knew best about the emergency measures in the Apollo command module, as he had been personally involved in developing the relevant procedures.

- In a joking response to the happy rescue, Grumman Aerospace Corporation , the lunar module designer , issued an invoice for $ 417,421.24 for "towing charges" to North American Rockwell , who in turn had built the command module and supply module, since the lunar module had the damaged one Spaceship was towed almost all the way to the moon and back. Said bill took into account a government discount of 20% and a cash discount of another 2% if North American should pay the sum in cash. However, North American politely refused to pay, pointing out that North American command capsules had already carried lunar lander from Grumman to the moon several times before, all without any request for payment.

See also

Literature / sources

- Christopher C. Kraft: Flight - My Life in Mission Control. Plume, New York 2002, ISBN 0-452-28304-3 .

- Eugene F. Kranz: Failure is not an option. Simon & Schuster, 2000, ISBN 0-7432-0079-9 .

- JA Lovell, J. Kluger: Lost Moon - The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13. Houghton Mifflin, Boston 1994, ISBN 0-395-67029-2 .

- NASA, Public Affairs Office, Washington, DC: Apollo 13 Press Kit. Release 70-50K; April 2nd, 1970.

- NASA, Manned Spacecraft Center, Houston, TX: Apollo 13 Mission Report. Document MSC-02680; Sept 1970.

- R. Orloff, D. Harland: Apollo - The Definitive Sourcebook. Springer, Berlin 2006, ISBN 0-387-30043-0 .

- Volker Neipp: With screws and bolts to the moon - the incredible life's work of Dr. Eberhard FM Rees. Springerverlag, Trossingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-9802675-7-1 . (Apollo 13 was the first mission Rees was responsible for as director of the MSFC.)

- Cay Rademacher : The dramatic flight of Apollo 13's odyssey in space. In: Geo Magazin. Issue 2 / February 1995, pp. 123-138.

- NASA (Ed.): Report of the Apollo 13 Review Board (Cortright Commission) . June 15, 1970 (English, stanford.edu [accessed February 3, 2019]).

Web links

- NASA: Complete Mission Description (English)

- NASA: Exactly recorded flight history (English)

- NASA: Extensive Apollo 13 photo collection (English)

- NASA: NASA's Apollo 13 link list (English)

- NASA: Apollo 13 Mission Reports (English, 168 and 345 pages)

- NASA: Report of the Cortright commission to investigate the accident (PDF; 8.7 MB, English)

- Apollo 13 in Real Time - multimedia processing of the mission based on original recordings

- Spiegel article from April 20, 1970 on Apollo 13 (also available there in PDF format)

Individual evidence

- ↑ NASA (ed.): Report of Apollo 13 Review Board Final Report . June 1, 1970, Document ID 19700076776 (English, nasa.gov ).

- ↑ NASA: Detailed Chronology of Events Surrounding the Apollo 13 Accident , Apollo 13 radio traffic recording (written), accessed on February 4, 2012 (English)

- ↑ A failure that became a lesson in the NZZ on October 14, 2018

- ↑ NASA The Spacecraft Communications Blackout Problem (PDF; 238 kB)

- ↑ Air & Space Did Ron Howard exaggerate the reentry scene in the movie Apollo 13?

- ↑ c / o Joachim Becker: Spacefacts. Retrieved October 19, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Report of the Apollo 13 Review Board (Cortright Commission) . June 15, 1970, Chapter 5 - Findings, Determinations, and Recommendations (English, large.stanford.edu/courses/2012/ph240/johnson1/apollo/docs/ch5.pdf [PDF; accessed February 3, 2019]).

- ↑ a b Mission Summary . In: Eric M. Jones, Ken Glover (Eds.): Apollo 13 Lunar Surface Journal.

- ↑ NASA's “finest hour”. (PDF) In: nasa.gov. April 2010, accessed September 28, 2019 .

- ↑ Astronaut Statistics in the Encyclopedia Astronautica , accessed on January 9, 2012 (English).

- ^ Copy of the invoice from Grumman Aerospace Corporation

- ↑ Jim Lovell, Jeffrey Kluger: Apollo 13. (previously titled Lost Moon). Pocket Books, New York 1995, ISBN 0-671-53464-5 , p. 335.