Spanish wind cake

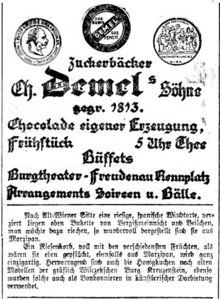

The Spanish wind cake is a historical dessert from Austria , which mainly consists of meringue and whipped cream . The first recipes for cakes made from sugar-coated protein snow are documented in Austrian writings from the late 18th century; detailed recipes then appeared around 1800 under the name of Spanish Wind Cake . At the First Viennese Confectionery Exhibition in October 1932, KuK Konditorei Ch. Demel's Söhne presented a Spanish wind cake that the press described as huge.

While it disappeared from German-language cookbooks in the middle of the 20th century , the Spanish wind cake experienced a revival in the United States thanks to a cookbook by journalist Joseph Wechsberg from the Time-Life cookbook series "Foods of the World" . In 2015 the Spanish wind cake was the subject of a British TV show. It is said to have been the model for the Pavlova meringue cake, popular in Australia and New Zealand .

Origin of name

The term “Spanish wind” for baked foam made from protein and sugar can be found very early on in old Austrian cookbooks. In 1818, the mouth cook FG Zenker pondered the origins of the Spanish winds:

“The apology of naming can be found in its properties, B. in their indescribable lightness compared to their volume, in the property of lovely atomization in the mouth u. like m .; but why they use the terms Spanish is perhaps more difficult to find. "

The “Illustrirte Lexicon der Gesammte Wirtschaftskunde” differentiated in 1854 between meringue (three lots of sugar on one egg white) and Spanish winds (only two lots of sugar on one egg white), today the terms meringue , meringue and Spanish wind are used synonymously, but one speaks depending according to the sugar content of light or heavy foam mass.

The English Time-Life cookbook The Cooking of the Viennese Empire (later: The Cooking of Vienna's Empire) wrote about the Spanish wind cake, among other things: “The Austrians call many super-elegant things Spanish, and that's the name of the foam made from sugar and egg white - known in other areas as meringue - in Austria 'Spanish wind' and is the basis of this fantastic cake. ”In March 1970, the New York Times commented on their published recipe for a Spanish wind cake that“ the Austrians and Germans have a special name for Vacherin to have. They call this the Spanish Wind Cake, which is truly romantic. ”The term“ Spanish Wind ”is still used for small baked meringues .

history

Austria

An old recipe called “Die gefrorne Tarten zumachen” (a so-called “frozen” cake made from wind mass) can be found in a Salzburg paper manuscript from 1785, but no filling is mentioned here. "Spanish winds" ( meringue ) filled with "Obers" ( cream ) is described in a cookbook from Graz in 1793 . Theresia Müller from Vienna left another manuscript with two recipes for Windtorte; this cookbook was apparently created around a manorial kitchen and was continued by several writers (perhaps daughters); only the last recipe was dated 1825. One recipe was called "The Just Wind Tarts" and another was "Die Eiß Torten", the latter turns out to be a wind cake in the description:

"The egg cakes: Make the dough, which you make the Spanish wind of, on a piece of paper, let it bake nice and cool, 3 sheets of cake belong on a whole cake, and meanwhile a sodden cake, on top make streak, color it with Schockoladi, the paper has to be removed beforehand. "

As Zenker explained, the so-called egg is nothing more than egg white with sugar that is stirred into a thick dough for at least a quarter of an hour.

The Spanish Wind Cake caused a sensation at the 1st Viennese Confectionery Exhibition , which took place from October 1st to 9th, 1932 in the Schönbrunn-Dreherpark. The Wiener Zeitung praised the confectioners Ch. Demel's sons , who were represented at the exhibition with “outstanding and unique pieces of confectionery art” with, for example, a representation of the Lusthaus in the Prater or a “giant Spanish wind cake according to old Viennese custom”. The Neue Freie Presse also praised the "huge Spanish wind cake according to old Viennese custom", which was decorated with bouquets of forget-me-nots and violets , so that "you want to smell it, they are so wonderfully presented made of marzipan". The Vienna pictures subsequently published a photo of the opening of the first Viennese pastry exhibition that showed on a display table a cake with attached bunch.

Franz Maier-Bruck writes in the historical cake chapter of his Große Sacher cookbook that in the Baroque period the pastry pie-shaped cakes were followed by what is considered a cake from today's perspective :

"A lush, foam-filled structure made of eggs, sugar, butter, snow and a little flour - a luxury product, low in vitamins and high in calories, a l'art-pour-l'art creation" under whose glaze Austria is ", as Ludwig Plakolb in" The world-famous Viennese cuisine "pointed."

A large number of such cake recipes appear in Austrian cookbooks from 1699, including the Spanish wind cake around 1800. In the 20th century it was apparently forgotten in Austria, Maier-Bruck's recipe for a coffee wind cake in 1975 no longer bears the nickname “Spanish”.

Revival abroad

In the USA , the Spanish wind cake became known in the 1960s through the 16-part cookbook series "Foods of the World" by the New York publisher Time-Life . Joseph Wechsberg, who had written about Austrian cuisine for The New Yorker in 1949 , was considered a gourmet in the USA. Therefore he was commissioned by Time-Life to write about the kitchen in the “Viennese Empire” (English : The Cooking of the Viennese Empire ), the nostalgic title should become one of the 16 series titles. The order is a spectacular honor and a contribution to western civilization, yes of global importance - as Time-Life claims to Wechsberg. Time-Life journalists and reporters traveled to various European cities for this cookbook series; in Vienna they “besieged” the Demel confectionery and photographed many real pies and cakes from the bakery. Wechsberg did his own research in Vienna, when the chapters were finished he sent them to New York.

A few months later, Wechsberg received a copy of the book, the cover showed the beautifully photographed Spanish wind cake, which, however, was not made by Demel in Vienna. As Wechsberg reports, the confectioners at Demel had never seen anything like it either. They were very impressed and amused because the photographer Fred Lyon had photographed the Spanish wind cake in the Time-Life building in New York, where an experimental kitchen had been set up, in which thousands of recipes from around the world for the cookbook series “ Foods of the World ”had been tried out, analyzed and described in detail. About the section on the Spanish wind cake in his book The Cooking of the Viennese Empire, Wechsberg reported in 1970 in his memorabilia The Ex-Expert :

"'Mastering Vienna's Pastry Magic' the description said, not written by me: Most beautiful of Vienna's round cakes, a baroque triumph in conception, design and execution, besides tasting of heaven, is the Spanische Windtorte."

“'Mastering the Viennese confectionery magic' it said in the description, but not written by me: The most beautiful of the round Viennese cakes, a baroque triumph in conception, design and execution, which also tastes heavenly, is the Spanish wind cake."

In 2015, the Spanish cake was presented in Great Britain as a technical challenge in the TV series The Great British Bake Off (episode 4 of the 6th series), its appearance in the series was cited as a reason for a later surge in popularity. The British The Daily Telegraph reported on the series that the Spanish cake was formerly referred to as “the fanciest cake in Vienna”.

Manufacturing

In his lesson "From Spanish Winds", Zenker described how the Spanish wind cakes were made from the same mass. The baking temperature was only 25 degrees on the Réaumur thermometer (31.25 ° C), the winds should get a "very nice chamois color"; Spanish winds in the Italian way, on the other hand, were "wonderfully white".

There are various ways of making Spanish wind cakes. The easiest way was to spread meringue mass on several wafers or baking paper the size of a dinner plate, dusting with a lot of powdered sugar and baking very slowly over very low heat, since the wind mass had to be absolutely dry and brittle. The cake bases were put together with different fillings. Another type was to dish large wreaths of meringue train so that a cream could be filled into the hollow center. The fillings were creams with different flavors (e.g. vanilla, mocca, coffee, marasquin , rum, caramel, rose blossom, orange blossom etc.), boiled fruit, “strawberry foam ” (cream foam with strawberries) or Frozen food made from raspberries, currants or sour cherries was filled in or came between and on top of every cake base. Variations of the Spanish wind cakes could be made with chopped nuts in the wind mass. Once filled, the Spanish wind cakes had to be served immediately.

Zenker wrote in 1818 about the decoration of the Spanish wind cake:

"The above ring can be decorated, but under the essential condition that the decoration is extremely simple and decent, because to embellish such a lovely beautiful surface, as it gives this pastry with careful treatment, by decoration, becomes a joke, if this does not perfectly correspond to its final purpose through beauty. "

The Spanish were decorated cakes with "confitirten" fruit (the obsolete name Confituren was both candied and for liquid cooked fruits) edged wind mass, or the edges of the baked pastry before baking or with "pearls".

Open cylinder shape

Franz G. Zenker presented practical instructions in 1818: Small Spanish winches were baked on wooden boards so that they only got a little lower heat; their center should remain soft so that they could be hollowed out and filled with cream. For the Spanish wind cake, four simple, equal-sized matures were baked from the mass to the Spanish winds on copper sheets, which generated good bottom heat. and made the wind mass "glass brittle". The diameter of the meringue ring should be nine inches and the empty center five inches. The baked matures were placed in a warming box for several hours to cool down slowly. Just before serving, you put the rings with apricot jam together, put them on a bowl and filled the opening with “foamed milk” (whipped cream). In order to give the cake some prestige, Zenker recommended double the mass, that is to say seven ripe ones with jam, the eighth ripe one uncoated at the end.

Cone shape with lid

In 1835, Josephine von Saint-Hilaire decorated a cone-shaped Spanish wind cake with a lid in her cookbook . The meringue is spread on round, plate-sized baking paper that tapers in size. Small Spanish winds are sprayed onto the edges of the meringue bases. For the lid, meringue strips are squirted crosswise onto baking paper, a “high button” is pressed in the middle and covered with dots the size of a pea. The gaps are finally sprayed with Spanish winds, no bigger than a hazelnut. The baking temperature of "the overcooled oven" is correct if you can put a bare arm into it.

Dome shape

In 1846, in his cookbook “The Kitchen of the Wealthy Viennese”, Zenker described two elaborate Spanish wind cakes (one of them with pistachios in the foam), of “beautiful, reddish-yellow color”, consisting of a dome over which the jam and is put on rings filled with cream. The dome should be large enough in diameter to fit inside the meringue rings. In the section “Some marked pieces relating to the art bakery”, Zenker describes cakes for the larger table with 12 place settings, including the more elaborately decorated Spanish wind cake: Spanish winds the size of a pigeon's egg were sprayed onto the rings and baked; When preparing the cake, this Spanish wind was decorated with "lively confitures" or the last hoop was decorated on the "surface" with apricots and beautiful sour cherries, placed on the bowl, the hollow center filled with "foamed cream" and the dome “Crowning the whole thing” superimposed on it.

The dome is described as difficult to remove from the baking paper and fragile. A dome is made from stiff paper over a round copper or sheet metal form, which is densely packed with small dots of egg whites and baked. It remains unfilled.

Additives

In her “very latest cookbook for meat and fast days” from 1804, the author Maria Anna Busswald gives tragacanth to the wind mass for the Spanish wind cake. The Viennese handwriting of Theresia Müller mentions two recipes made from wind mass, using a "Haßelnut-sized tragand" for "The just wind cakes".

A previously specially baked plate made of "Dragant sugar" served for stability, the wind cake was built on this tragacanth shell and then placed on the bowl. The Codex Alimentarius austriacus allowed since 1911 for wind bakery no longer the use of impure, not odorless and tasteless glue and the addition of alum .

Serve

In the historical sources there are many suggestions for serving the wind cakes on a bowl covered with napkins. Confectioners used special porcelain plates with a high rim for wind cakes. Was no such pie dish at hand, could a "wind pie plate" tinkering by a flat plate the edge of a springform pan set and him with a papery harmonica ring decorated.

Pavlova

As Maike Vogt-Lüerssen writes, German settlers brought the Spanish wind cake recipe to the USA in the 19th century, from where it went to Australia, then later to New Zealand and became the popular Pavlova meringue cake , named after a Russian ballet dancer.

Literary use

In the story Die Freiherren von Gemperlein by Marie Freifrau von Ebner-Eschenbach (1889) an excited cook pours gravy over the Spanish wind cake instead of chocolate.

literature

- Joseph Wechsberg : Spanish wind cake . In: The kitchen in the Viennese Empire . Time-Life International, Amsterdam 1976, DNB 1090804989 (English: The cooking of Vienna's empire . 1968. Translated by Sabine Specht, Authorized German edition).

Individual evidence

- ^ Felix Czeike: Historical Lexicon Vienna. www.digital.wienbibliothek.at, p. 259 , accessed on February 25, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c Franz G. Zenker: Theoretical-practical instructions for art bakery. In: SLUB Dresden. Printed by Anton Strauss - Vienna, 1818, pp. 308–312 , accessed on February 22, 2019 .

- ^ Löbe, William: Illustrirtes Lexikon der Gesamt Wirtschaftskunde / Löbe, William | Illustrated lexicon of all economics. In: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek - Munich. Löbe, William, p. 500 , accessed February 21, 2019 .

- ↑ Claus Schünemann, Günter Treu: Technology of the production of baked goods: specialist textbook for bakers . 10th revised edition. Gildebuchverlag GmbH, 2009, ISBN 978-3-7734-0150-2 , p. 320 ( google.de [accessed on February 24, 2019]).

- ↑ a b c d Joseph Wechsberg: The First Time Around: Some Irreverent Recollections . 1st edition. Little, Brown & Company (Canada) Limited, Boston / Toronto 1970, The Ex-Expert, S. 373-376 .

- ↑ Craig Claiborne: M-m-m-m-meringue . In: The New York Times . May 17, 1970, ISSN 0362-4331 ( nytimes.com [accessed February 15, 2019]).

- ↑ "GuteKueche.at: Spanish Wind" . Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ↑ Making the Frozen Tarts. MI 382nd Department for Special Collections of the Salzburg University Library, pp. 10r-10v , accessed on February 24, 2019 .

- ↑ Inexhaustible household and economic magazine - second volume . Johann Andreas Kienriech, Grätz 1793, p. 61 ( google.de [accessed February 15, 2019]).

- ^ The cookbook manuscript 1967 Cookbook and pharmacopoeia of Theresia Müller in Vienna. sosa2.uni-graz.at, accessed on March 1, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Hans Zotter: This book belongs to Antonia Müller, Vienna - UBG Ms. 1967: Transkription. sosa2.uni-graz.at, 2008, pp. 31, 36 , accessed on March 1, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c F. G. Zenker: Zuckerbaecker for women of middle class. From Spanish winds. In: SLUB Dresden. Claus Haas, 1824, pp. 54–58 , accessed on March 3, 2019 (German).

- ↑ Ch. Demel's sons at the confectioner exhibition. In: ANNO - Austrian National Library Vienna. Wiener Zeitung, October 7, 1932, p. 6 , accessed on February 15, 2019 .

- ^ First Viennese confectionery exhibition 1.-9. Oct. 1932 Schönbrunn-Dreherpark. In: ANNO - Austrian National Library Vienna. Neue Freie Presse, October 5, 1932, p. 8 , accessed on February 16, 2019 .

- ^ Opening of the First Viennese Confectionery Exhibition. In: ANNO - Austrian National Library Vienna. Wiener Bilder, October 9, 1932, p. 4 , accessed on March 3, 2019 .

- ^ Franz Maier-Bruck: The great Sacher cookbook . Wiener Verlag, Vienna 1975, p. 558, 560 .

- ^ Time Inc: LIFE . Time Inc, October 25, 1968 ( google.de [accessed February 27, 2019]).

- ↑ Linda Collister: Great British Bake Off: Celebrations: With recipes from the 2015 series . Ed .: Hodder & Stoughton General. Hodder & Stoughton, 2015, ISBN 978-1-4736-1534-2 ( google.de [accessed February 24, 2019]).

- ↑ "Spanish Wind cake" - Google Trends: Worldwide trends .

- ↑ What on earth is a Spanish wind cake? . In: The Daily Telegraph , August 26, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ "Fabulous Foods of the World, Just 50 Cents" . June 11, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ↑ Sybilla Dorizio: My cookbook for large and small tables, 1816, which has been known through forty years of practice and so far only through oral communication .

- ↑ a b c d Anton Hüppmann: The elegant palate A theoretically practical work of fine culinary art; According to the best German and French methods, it contains instructions for the preparation of 400 of the finest rumors and 140 explanatory illustrations . Ed .: Austrian National Library. Printed by Landerer v. Füskut, 1835, p. 248–249 ( archive.org [accessed February 15, 2019]).

- ↑ Strawberry Tree. In: Rosina Kastner: Complete Tyrolean cookbook for German and local cuisine. Wagner, 1844. pp. 449-450.

- ↑ The latest and most complete Innsbruck cookbook: written and compiled according to the best and most accurate experience. State Library Dr. Friedrich Teßmann I-39100 Bozen, p. 111 , accessed on February 15, 2019 .

- ↑ a b J. SH: The true art of cooking or the latest checked and complete Pesther cookbook ... From a woman who is well experienced in the art of cooking (etc.) 6., verm. And verb. Ed . Eggenberger, 1835, p. 361 ( google.de [accessed on February 15, 2019]).

- ^ A b F. G. Zenker: The kitchen of the wealthy Viennese, or the latest general cookbook Containing a careful and complete selection of the most tried and tested recipes for the best and tastiest preparation of all types of meat, fish and pastries, in addition to art bakery, and the simmering of fruits . Ed .: Austrian National Library. Jasper'sche Buchhandlung, Vienna 1846, p. 252, 277, 279 ( archive.org [accessed February 24, 2019]).

- ↑ Maria Anna Busswald: The very latest cookbook for meat and fast days . Second increased edition. Alois Tusch, Grätz 1804, p. 189 ( google.de [accessed on February 27, 2019]).

- ↑ a b General Austrian or the latest Viennese cookbook: useful in every household, or the art of cooking for stately and bourgeois tables . Published by Mörschner and Jasper, 1831, p. 737 ( google.de [accessed February 20, 2019]).

- ^ Commission for the publication of the Codex alimentarius austriacus (ed.): Codex alimentarius austriacus . tape 1-2 . Verlag der KK Hof- und staatsdruckerei, Vienna 1911, p. 325 .

- ↑ Windbusserl. In: ANNO Austrian National Library 1015 Vienna, Austria. Grazer Tagblatt - Deutsche Frauenzeitung, February 16, 1913, p. 19 , accessed on February 18, 2019 .

- ↑ Maike Vogt-Lüerssen: Love really goes through the stomach: My family's favorite recipes . BoD - Books on Demand, 2016, ISBN 978-3-8370-9594-4 , pp. 89 ( google.de [accessed on February 15, 2019]).

- ↑ Marie Freifrau von Ebner-Eschenbach: The barons von Gemperlein: story . tredition, 1889, ISBN 978-3-8424-0702-2 , p. 43 ( google.de [accessed on March 19, 2019]).