St. James's Day Fight

| date | August 4. bis 5. August 1666 |

|---|---|

| place | Coast of England, North Sea |

| output | English victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 90 warships 16 fires 4,854 cannons 23,142 men |

91 warships 20 Brander 4,645 cannons 22,234 men |

| losses | |

|

1 warship |

2 warships |

The St. James's Day Fight (also known as the Sea Battle at North Foreland or Tweedaagse Zeeslag ) on July 25th jul. / 4th August 1666 greg. was a naval battle during the Anglo-Dutch War (1665–1667). The English fleet under the command of Prince Rupert and Admiral George Monck attacked the Dutch navy under Admiral Michiel de Ruyter off the English coast. The battle ended with a victory for the Royal Navy, which achieved naval supremacy. The battle got its name because it took place on July 25th, the name day of Saint James , according to the Julian calendar then valid in England .

prehistory

The Republic of the United Netherlands and the Kingdom of England had been at war for economic advantage since the spring of 1665. Despite a few battles, neither side had gained a decisive advantage. In June 1666 there was finally the " Four Days Battle " (June 11-14, 1666), in which the Dutch achieved a great success over the English fleet. The English lost 10 ships. 30 others were badly damaged. They had to retreat to the docks on the banks of the Thames and let the Dutch warships rule the sea. While the Dutch blocked the Thames estuary, the English associations were preparing to clear this important trade route.

The Dutch fleet

Shortly after the "Four Days Battle" overestimated Johan de Witt (1625-1672), the Grand Pensionary of Holland , in which the management of the Dutch policy was the extent of the English defeat. He believed that it would take the English fleet a long time to repair the damage to their ships, and he doubted that they had the materials at all. He also expected that the defeat would lead to unrest among the English population, which would encourage Dutch troops to land in England. On June 24 jul. / 4th July 1666 greg. he sent the fleet under the command of Admiral Michiel de Ruyters (1607–1676) again. In addition to the warships, it also included many transport ships on which troops were waiting for a landing. But de Witt did not come across the remnants of the English fleet, nor did he encounter an uprising movement of the local population at the Thames estuary. The Dutch fleet therefore had no choice but to close the Thames estuary to English trade in order to force them to peace on this route.

The Dutch fleet included 77 warships, 17 simple Frigate and 2 three-mast Frigate and 7 smaller boats and 20 Brander with a total of 22,234 sailors and 4,645 guns. This made her the number of the English fleet, but her ships were smaller and her cannons were of lesser caliber. In terms of firepower, the Dutch were therefore not up to the English fleet. The fleet itself was divided into three squadrons. The first squadron commanded Admiral de Ruyter himself, the second commanded Admiral Johan Evertsen (1600–1666) and the third finally Admiral Cornelis Tromp (1629–1691). Each squadron was itself divided into advance guard, rear guard and center ( → see: table below ).

| SECOND SQUADAR (Jan Evertsen) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admiralty | ship | Cannons | crew | captain |

| F. | Groot Frisia | 72 | 413 | LA Tjerk Hiddes de Vries |

| F. | Groningen | 70 | 341 | VA Rudolf Coenders |

| F. | Prince Hendrik Casimir | 70 | 392 | SbN. Hendrik Bruynsvelt |

| F. | Sneek | 65 | 326 | Ruyrt Hillebrantszoon |

| F. | Oostergo | 60 | 275 | Jan Janszoon Vijselaar |

| F. | Westergo | 56 | 230 | Wytse Beyma |

| F. | Eleven cities | 54 | 236 | Barend Hiddes de Vries |

| F. | Prinses Albertina | 50 | 213 | Pieter Feykeszoon Eykema |

| F. | Omlandia | 48 | 206 | Christiaan Ebelszoon |

| F. | Little Frisia | 38 | 191 | Jan Pieterszoon Vinckelbos |

| Z | Walcheren | 70 | 380 | LA Jan Evertsen |

| Z | Tholen | 60 | 296 | VA Adriaan Banckert |

| Z | Zierikzee | 58 | 317 | SbN. Cornelis Evertsen the Elder J. |

| Z | Middelburg | 50 | 217 | Jacob Adrianszoon Pens |

| Z | Vlissingen | 50 | 210 | Jan Matthijszoon |

| Z | Kampveere | 50 | 218 | Adriaan de Haaze |

| Z | Utrecht | 50 | 220 | Jan Pieterszoon aunt |

| Z | Dordrecht | 49 | 200 | Adriaan van Cruiningen |

| A. | City of Gouda | 46 | 230 | Dirk Scheij |

| A. | Dom van Utrecht | 46 | 228 | Jacob Willenszoon Broeder |

| A. | Stavoren | 46 | 230 | Jacob Pauw |

| A. | Wakende Boei | 46 | 229 | Hendrik Vroom |

| A. | Zone | 44 | 198 | Floris Floriszoon Bloem |

| Frigates | ||||

| Z | Zeeridder | 34 | 175 | Willem Marinissen |

| Z | Delft | 34 | 1698 | Dirk Jacobszoon Kiela |

| Z | Zeelandia | 34 | 173 | Abraham Crijnssen |

| Z | Schakerlo | 29 | 147 | Cornelis Evertsen the Elder Youngest |

| Z | Visscher's Harder | 26th | 105 | Jan Adrianszoon Blanckert |

| Yachts | ||||

| Z | Prins te Paard | 14th | 75 | Willem Hendrikszoon van der Veere |

| Z | Zouteland | 6th | 29 | Klaas Reinierszoon |

| Z | Dishoek | 6th | 21st | Gilles Geleynszoon |

| Z | West Souburg | 6th | 13 | Frans Roys |

| Z | East Souburg | 6th | 13 | Daniel Verdiest |

| Fire | ||||

| Z | Eendracht | 2 | 8th | Willem Meerman |

| Z | Hoop | 4th | 14th | Angel Adriaanszoon |

| F. | Prinses | 3 | 16 | Meindest Jentjes |

| M. | Fortuin | 2 | 9 | Jan Danielszoon van den Rijn |

| M. | Schiedam | 4th | ? | Gerrit Andrieszoon Mak |

| M. | Erasmus | ? | ? | Bartel Evertszoon light |

| FIRST SQUADRON (Michiel de Ruyter) | ||||

| Admiralty | ship | Cannons | crew | captain |

| Vanguard division | ||||

| M. | Eendracht | 71 | 402 | LA Ært van Nes |

| M. | Groot Hollandia | 65 | 311 | Laurens Davidszoon van Convent |

| M. | Prinses Louise | 40 | 200 | Frans van Nijdek |

| A. | Provincie Utrecht | 64 | 273 | Jacob Corneliszoon Swart |

| A. | Gouden Leeuwen | 52 | 251 | Enno Doedes star |

| A. | Tromp | 46 | 245 | Hendrik van Vollenhoven |

| A. | Harderwijk | 44 | 220 | Thomas Tobias |

| M. | Wapen van Utrecht | 36 | 149 | Eland du Bois |

| M. | Nijmwegen | 34 | 130 | Willem Boudewijnszoon van Eyk |

| M. | Swol (yacht) | 16 | 58 | Pieter Wijnbergen |

| M. | Lijdzaamheid (fs) | 2 | 10 | Cornelis Jacobszoon van der Horven |

| M. | Helena (fs) | 2 | 10 | Jan Broerszoon Vermeulen |

| M. | Delft (fs) | 4th | ? | Willem Pauluszoon |

| Main division | ||||

| M. | Delft | 62 | 304 | SbN. Jan Janszoon van Nes |

| A. | Wapen van Utrecht | 66 | 290 | Hendrik Gotskens |

| A. | Cities in the country | 58 | 280 | Hugo van Nieuwenhof |

| A. | Zuiderhuis | 50 | 243 | Cornelis van Hogenhoeck |

| M. | Zeven Provincia | 80 | 492 | Adm. Gene. Michiel de Ruyter |

| M. | Gelderland | 66 | 360 | Willem Joseph van Ghent |

| M. | Little Hollandia | 54 | 244 | Evert van Gelder |

| M. | Wassenaar | 58 | 254 | Ruth Maximiliaan |

| A. | Vrede | 46 | 230 | Jan du Bois |

| M. | Gorinchem | 34 | 130 | Huybert Jacobszoon Huygen |

| M. | Schiedam | 22nd | 80 | Jacob Pieterszoon Swart |

| M. | Lopende Hert (yacht) | 8th | 20th | Dirk de Munnik |

| M. | Lammertje Kweek (fs) | 2 | 11 | Jan van Brakel |

| M. | Rotterdam (fs) | ? | ? | Gysbert Jacobszoon de Hay |

| F. | Eckster (fs) | 2 | 11 | Reiner de Vos |

| Rearguard division | ||||

| M. | Ridderschap | 66 | 364 | VA Jan de Liefde |

| M. | Dordrecht | 46 | 200 | Philips van Almonde |

| A. | Geloof | 64 | 335 | Nicolaas Marrevelt |

| A. | Amsterdam | 62 | 294 | Jacob van Meeuwen |

| A. | Raadhuis van Haarlem | 46 | 232 | Jan de Jong |

| A. | Huis te Jaarsveld | 44 | 216 | Jost Verschuur |

| N | Wapen van Nassau | 60 | 285 | David Vlugh |

| N | Hollandse Tuin | 56 | 244 | Jan Crook |

| M. | Vrede | 34 | 118 | Juriaan Juriaanszoon Poel |

| M. | Harderwijk | 32 | 141 | Nicolaas Naalhout |

| M. | Goede Hoop (fs) | 2 | 12 | Pieter Lievenszoon |

| THIRD SQUADER (Cornelis Tromp) | ||||

| Admiralty | ship | Cannons | crew | captain |

| N | West Friesland | 78 | 398 | LA Jan Corneliszoon Meppel |

| N | Pacificatie | 73 | 354 | VA Volckert Schram |

| N | Jozua | 54 | 242 | SbN. Govert't Hoen |

| N | Maagd van Enkhuizen | 72 | 312 | Pieter Kerseboom |

| N | Gelderland | 64 | 288 | Johan Belgicus |

| N | Jonge Prins | 62 | 274 | Hendrik Visscher |

| N | Noorderkwartier | 58 | 275 | Pieter Klaaszoon Wijnbergen |

| N | Wapen van Holland | 48 | 226 | Cornelis Jacobszoon de Boer |

| N | Three heroes of David | 48 | 224 | Adriaan Teding van Berkhout |

| N | Caleb | 47 | 304 | Jan Hek |

| N | Wapen van Medemblik | 46 | 200 | Klaas Valchen |

| N | Eendracht | 44 | 188 | Klaas anchor |

| A. | Hollandia | 80 | 450 | LA Cornelis Tromp |

| A. | Gouda cheese | 71 | 368 | VA Isaac Sweers |

| A. | Troublemaker | 52 | 284 | SbN. Willem van der Zaan |

| A. | Reiger | 72 | 346 | Hendrik Adriaanszoon |

| A. | Calantsoog | 72 | 305 | Jan de Haan |

| A. | Oosterwijk | 68 | 313 | François Palm |

| A. | Deventer | 66 | 289 | Jacob Andrieszoon Swart |

| A. | Vrijheid | 58 | 258 | Jan van Amstel |

| A. | House Tijdverdrijf | 56 | 291 | Thomas Fabritius |

| A. | United Provincia | 48 | 230 | Jacob Binckers |

| A. | Kampen | 46 | 231 | Michiel Suis |

| A. | Haarlem | 42 | 209 | Pieter van Middelland |

| A. | Edam | 37 | 147 | Pieter Magnussen |

| Frigates | ||||

| N | Wapen van Hoorn | 30th | 150 | Gerrit Klaaszoon Posthoorn |

| N | Castle van Medemblik | 30th | 127 | Jan Mauw |

| A. | Asperen | 34 | 140 | Jan Gijselszoon van Lier |

| A. | Harder | 34 | 136 | Jan Davidszoon Bont |

| A. | IJlst | 32 | 140 | Jacob Dirkszoon boom |

| A. | Overijssel | 30th | 120 | Arend Symonszoon Vader |

| Yachts | ||||

| A. | ? | ? | ? | Jan Janszoon Verboekelt |

| A. | ? | ? | ? | Pieter Martenszoon |

| Fire | ||||

| A. | Bristol | 4th | 14th | Hendrik Dirkszoon Boekhoven |

| A. | Eenhoorn | 4th | 14th | Purely Pieterszoon Mars |

| A. | Brak | 4th | 14th | Henricus Roseus |

| A. | Wapen van London | 4th | 14th | Gerrit Floriszoon |

| M. | Pro Patria | ? | ? | Joost Gilleszoon |

| M. | Reus | ? | ? | Jacob Martszoon de Haas |

The English fleet

In the case of the English fleet, the initial aim was to make up for the personnel losses in the “four-day battle”. The naval administration took drastic measures to this end. " Pressgangs " were sent out to force sailors into the Royal Navy. From the capital alone, 2,750 men were lifted, to which hundreds more from the other coastal cities and 2,000 soldiers came. The repair of the ships themselves was quick. As early as the first week of July, enough ships were gathered to face the Dutch fleet again. Nevertheless, the naval command waited for the completion of some new large warships, such as the Loyal London (92 cannons), Warspite (64 cannons), Cambridge (64 cannons) and Greenwich (58 cannons). It was only when they joined the fleet that it was decided to attack again.

The naval command also evaluated the mistakes of the previous defeat and issued new regulations. They said that from now on the individual ships should stick closer to their own flagship in order to increase the cohesion of the squadrons. Flag signals always had to be passed on and finally orders were made which regulated the change of flag (change of the commanding admiral to another ship).

The Royal Navy finally had 87 warships of the fourth to first class (i.e. ships with more than 30 cannons), 3 warships of the fifth and sixth class, and 16 Brander for their attack. Among the ships were 10 hired merchant ships. In total, the fleet numbered 23,142 seamen and 4,854 cannons. The ships themselves were on average larger than those of their Dutch opponents and the caliber of the cannons also exceeded that of the Dutch. The English fleet had thus secured at least a qualitative preponderance for the intended armed forces . The supreme command led Prince Rupert , Duke of Cumberland (1619-1682) and George Monck , Duke of Albemarle together (1608-1670) as a joint admirals . Among them, the English fleet was divided into three sub-units, each with vanguard, rear guard and center. The White Squadron was under the command of Admiral Sir Thomas Allin (1612-1685) and the Blue Squadron commanded Admiral Sir Jeremiah Smith († 1675). The main power, the Red Squadron , commanded the joint admirals directly. ( → see: table below )

| WHITE SQUADRON (Sir Thomas Allin) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | ship | Cannons | crew | captain |

| Van division | ||||

| M. | London Merchant | 48 | 180 + 30 | Amos Beare |

| 3 | Anne | 58 | 280 + 30 | Robert Maulton |

| M. | Baltimore | 48 | 180 | John Day |

| 4th | Guinea | 38 | 150 | Arthur Ashby |

| 4th | expedition | 34 | 140 | Tobias Sackler |

| 2 | Royal Katherine | 76 | 500 | VA Sir Thomas Teddeman |

| 4th | Dover | 30th | 170 | Jeffery Pearse |

| 2 | St. George | 66 | 360 + 40 | John Hayward |

| 3 | Dunkirk | 58 | 280 | John Waterworth |

| Main division | ||||

| M. | Richard & Martha | 50 | 200 | George Colt |

| 3 | Montagu | 58 | 300 | Daniel Helling |

| 4th | Centurion | 48 | 180 | Charles Wild |

| 4th | leopard | 60 | 300 | John Hubbart |

| 4th | Assistance | 46 | 170 | Zachary Brown |

| 1 | Royal James | 82 | 570 | Adm. Sir Thomas Allin |

| 4th | Dragon | 40 | 160 | Thomas Room Coyle |

| 4th | Delft | 40 | 160 | Edward Cotterell |

| 2 | Old James | 70 | 380 | Edmund Seaman |

| 3 | Plymouth | 58 | 280 | John Lloyd |

| 4th | Assurance | 38 | 150 | John Narbrough |

| Rear division | ||||

| 4th | Kent | 46 | 170 | John Silver |

| M. | Coronation | 52 | 190 | William Davis |

| 3 | Helverston | 60 | 260 | Abraham Ansley |

| 4th | Hampshire | 42 | 160 | William Coleman |

| 3 | Rupert | 64 | 370 | RA Richard Utber |

| 4th | West Friesland | 52 | 180 | John Butler |

| 3 | York | 58 | 280 | John Swanley |

| 2 | Unicorn | 60 | 320 | George Batts |

| 4th | Mary Rose | 50 | 185 + 20 | Thomas Darcy |

| Fire | ||||

| fs | Providence * | 10 | 45 | John Wood |

| fs | Fortune * | 6th | 35 | William Lee |

| fs | Richard | 4th | 45 | Henry Brown |

| fs | Paul | 4th | 50 | Daniel Stephans |

| fs | Jacob | 4th | 40 | William Humble |

| RED SQUADRON (Prince Rupert / Duke of Albermale) | ||||

| Type | ship | Cannons | crew | captain |

| yacht | Bristol | 48 | 200 | John Hart |

| Van division | ||||

| M. | Bristol | 48 | 200 | John Hart |

| 3 | Gloucester | 58 | 280 | Robert Clark |

| 3 | Royal Exchange | 46 | 260 | Giles Shelley |

| 4th | Diamond | 46 | 180 | John King |

| 2 | Martin Galley | 14th | 65 | Richard White |

| 4th | Royal Oak | 76 | 450 | VA Sir John Lawson |

| 4th | Norwich | 24 | 135 | John Wetwang |

| 4th | Guinea | 36 | 150 | John Abelson |

| 4th | St. George | 60 | 360 | Joseph Jordan |

| Main division | ||||

| 2 | Coast Frigate | 34 | 150 | Thomas Lawson |

| 3 | Dover | 46 | 170 | Jeffery Pearse |

| 4th | King Ferdinando | 36 | 180 | Francis Johnson |

| 5 | Plymouth | 56 | 280 | Thomas Allin |

| 1 | Fountain | 30th | 150 | Jean Baptiste du Tiel |

| 3 | Blackamore | 38 | 170 | Richard Neals |

| 4th | Mary | 58 | 300 | Jeremy Smith |

| 5 | Happy return | 50 | 145 | James Lambert |

| 1 | Drake | 12 | 85 | Richard Poole |

| 6th | Royal Charles | 78 | 550 | Sir William Penn / John Harman |

| 4th | Mermaid | 28 | 145 | Jasper Grant |

| 3 | Fame | 12 | 45 | John Gethings |

| 4th | Bramble | 8th | 35 | Nepthali ball |

| 2 | Antelope | 46 | 180 | John Chicheley |

| 3 | Old James | 68 | 380 | Earl of Marlborough |

| Rear division | ||||

| 4th | Loyal George | 42 | 190 | John Earle |

| M. | Yarmouth | 52 | 190 | Thomas Ayliffe |

| 3 | Vanguard | 56 | 320 | Jonas Poole |

| 4th | Convertine | 48 | 180 | John Pearce |

| 2 | Charity | 46 | 170 | Robert Wilkinson |

| 4th | eagle | 44 | 220 | Thomas Hendra |

| 3 | Amity | 36 | 150 | John Parker |

| 4th | Satisfaction | 46 | 180 | Richard May |

| 4th | Fairfax | 58 | 300 | Robert Salmon |

| Fire | ||||

| fs | Swiftsure | 60 | 380 | RA Sir William Berkeley |

| fs | Bonaventure | 40 | 160 | Arthur Laughorne |

| fs | Portsmouth | 38 | 160 | Robert Mohun |

| fs | George | 40 | 180 | Robert Hatubb |

| fs | leopard | 54 | 240 | Richard Beach |

| fs | Sapphire | 38 | 160 | Henry Hyde |

| fs | Loyal Merchant | 44 | 210 | Robert Sanders |

| RED SQUADRON (Prince Rupert / Duke of Albermale) | ||||

| Type | ship | Cannons | crew | captain |

| Van division | ||||

| M. | Forester | 28 | 145 | Edward Cotterell |

| M. | Royal Katherine | 70 | 450 | RA Thomas Teddiman |

| 4th | Essex | 52 | 52 | Richard Utber |

| 3 | Marmaduke | 38 | 150 | John Best |

| 4th | Princess | 52 | 220 | George Swanley |

| 3 | Golden Phoenix | 36 | 160 | Samuel Dickenson |

| 4th | Adventure | 36 | 150 | Benjamin Young |

| M. | Society | 36 | 160 | Ralph Lascelles |

| Main division | ||||

| 3 | Dreadnought | 58 | 280 | Henry Tearne |

| 2 | Prudent Mary | 36 | 160 | Thomas Harward |

| 3 | Dragon | 38 | 160 | John Lloyd |

| 3 | Centurion | 46 | 180 | Robert Moulton |

| 4th | Montagu | 58 | 300 | Henry Fenne |

| 2 | Oxford | 24 | 135 | Philip Bacon |

| 4th | Prince | 86 | 700 | Roger Cuttance |

| 3 | Pembroke | 28 | 145 | Thomas Darcy |

| 4th | Bryar | 12 | 45 | Richard Cotton |

| 4th | Dunkirk | 54 | 260 | John Hayward |

| 4th | Breda | 46 | 180 | Robert Kirby |

| Rear division | ||||

| M. | John & Thomas | 44 | 200 | Henry Dawes |

| 4th | Swallow | 46 | 180 | Richard Hodges |

| 2 | Madras | 42 | 180 | John Norbrook |

| 4th | jersey | 48 | 190 | Hugh Hide |

| 2 | Hambro 'Merchant | 36 | 170 | James Cadman |

| 4th | Hampshire | 40 | 160 | George Batts |

| 3 | Castle Frigate | 36 | 160 | Philip Euatt |

| 4th | Assistance | 40 | 170 | Zachary Brown |

| 4th | Nicorn | 56 | 320 | Henry Teddiman |

| Fire | ||||

| fs | Providence | 30th | 140 | Richard James |

| fs | York | 58 | 280 | John Swanley |

| fs | Henry | 70 | 430 | VA Sir George Ayscue |

| fs | guernsey | 28 | 145 | Humphrey Connisby |

Course of the battle

Approach of the fleets

Prince Rupert and Admiral Monck waited until the wind allowed the entire English fleet to be carried down the Thames at once so that it would not be attacked separately from the Dutch waiting there. On August 1st, the English ships appeared in the Thames estuary. Admiral De Ruyter wanted to avoid fighting in the coastal waters he did not know well enough. He therefore withdrew in a southerly direction out onto the open sea. On the night of August 2, a storm prevented any action, and on August 3, both fleets shadowed each other as they repaired the damage from the previous storm. Both associations had meanwhile taken an easterly course.

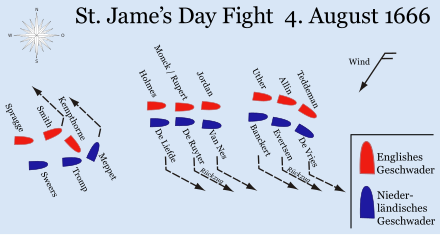

On the morning of August 4, 1666, both fleets formed their battle lines parallel to each other. At this point they were about 20 kilometers southeast of Orfordness . The English sailed north of the Dutch line and thus took up the advantageous windward position from which they could initiate an attack at any time. There were problems with the formation of the keel line on the part of the Dutch fleet . The vanguard under Admiral Evertsen sailed faster than the center under Admiral De Ruyter, creating a gap between these two squadrons. At the same time there were still a few ships of the center association between ships of the rearguard of Admiral Tromp. The admiral decided to wait until they had separated from him and therefore hardly made any speed. This created a wide gap between the rear and the center. As an additional problem it turned out that the Dutch central squadron was a little further south than the other units. Admiral De Ruyter made no move to gain the windward position himself by maneuvers, but remained passively in the lee to await the English attack. Probably the prevailing opinion on the Dutch side was that after the losses in the last battle the new English fleet could only consist of weak merchant ships and that the Dutch ships therefore had the superiority of fire.

The fire fight until the afternoon

The English fleet now started the attack. Prince Rupert and Admiral Monck had originally planned to bring all three squadrons to the enemy at once. However, this failed and so initially only the two vanguard came into contact. The Dutch squadron under Admiral Evertsen began firing at Admiral Allin's White Squadron at about 9:30 a.m. This returned fire from around 10:00 a.m. An hour later, the two opposing central squadrons came into play with each other and only at 12:00 noon did a fire fight develop between the rear guards. At that time, almost 5,000 cannons were in use. Due to the large gaps in the Dutch keel line, the battle was divided into these three separate sections almost from the start.

The skirmish between the English and Dutch vanguard soon revealed the superior firepower of the White Squadron . Thanks to their windward position, the English were able to use their fire engines. But these turned out to be too slow because of the weak wind and were stopped by the Dutch broadsides before they could reach their destination. But the firepower of the English ships soon brought the Dutch vanguard into trouble. By 2:00 p.m. she lost five admirals, including Tjerk Hiddes de Vries, Rudolf Coenders and Johan Evertsen himself. The head of the Dutch squadron was then pushed to the southeast by the English Van Division under Vice Admiral Sir Thomas Teddeman . At 3:00 p.m. the remnants of the squadron began a disorderly retreat.

This sequence seemed to be repeated in the center. Here, too, the superiority of fire lay on the part of the English. The two flagships , the British Royal Charles (82 cannons, 700 men) and the Dutch Zeven Provinciën (80 cannons, 492 men) were involved in a fierce duel from which the joint admirals had to withdraw. After that, however, the Dutch flagship was attacked by the Royal Sovereign (102 cannons, 800 men). This largest English warship had previously successfully fought the escort ships of the Zeven Provinciën ( Gelderland, Klein Hollandia and Wassenaar ) and now took the place of the Royal Charles, who left the association . A Dutch attempt at around 3 p.m. to use a fire against the Royal Sovereign failed with the sinking of the incendiary ship. Now she fought the Dutch flagship, which had to leave the Dutch battle line until shortly before 4:00 p.m. due to the major damage. As a result, after the advance guard, the entire Dutch main squadron turned to retreat south.

The battle of the rear guards

The fight with the rear guards was different. Here Admiral Tromp had the strongest Dutch squadron and was superior to his English opponent - Admiral Smith with the Blue Squadron - in terms of the number of cannons and crews . The Van Division of the Blue Squadron , commanded by Rear Adm. John Kempthorne, was first caught in the Dutch fire and soon suffered casualties. The captain of the Elisabeth fled with his ship and the East India London was shot down. At around 3:00 p.m. the Resolution (58 cannons, 300 men) lost its top mast and drifted towards the Dutch line, unable to maneuver. The rest of the division tried to come to her aid and turned a direct course south on the Dutch line. Nevertheless, the ship was sunk by a Dutch fire. 200 sailors drowned. Rear Admiral Kempthorne put his division back on a course parallel to the Dutch line.

Kempthoe's relief efforts for the resolution brought disorder to the English line. The Center Division, under Admiral Smith's personal leadership, now had to take over the head of the line, passing Kempthorne. At the same time, however, the Dutch advance guard division under Admiral Meppel remained without an English counterweight, as Kempthorne had temporarily no longer run parallel to it. The Dutch admiral took this opportunity and turned north to gain the windward position and encompass the Blue Squadron . This maneuver lasted until around 5:00 p.m. Admiral Smith's division came into action with Admiral Meppel's division only afterwards and both were now moving on a northwesterly course while the other divisions continued to move eastwards. At around 6:00 p.m., however, the other two English divisions also turned away and followed Admiral Smith's division. The Dutch pursued them and the fight moved away from the “battlefield” of the main forces, which at this point were already retreating in the opposite direction to the southeast. A total of 28 English and 35 Dutch ships were therefore no longer under the authority of their commanders-in-chief.

The reports about the further course of the battle between the opposing rearguards contradict one another. Admiral Smith stated that he had put the Dutch to flight, while Admiral Tromp claimed that he had pursued the English and only broke off this pursuit on hearing that the main fleet had been defeated. All that can be proven is that the Dutch Rear Admiral Govert't Hoen died during the battle; that Admiral Smith's flagship, the Loyal London (92 cannons, 600 men), suffered losses of 147 men and Admiral Meppel's ship, the Westfriesland (78 cannons, 398 men), lost around 100 men.

The pursuit of the Dutch squadron

In the meantime the Dutch vanguard and the center were retreating to their own coastal waters. Since the Dutch preferred to shoot the sails and rigging of the English ships in battle, they had a slight advantage in terms of speed. Only two Dutch ships were finally overtaken by the pursuing English. At around 6:00 p.m. the Sneek (65 cannons, 326 men) surrendered to the Royal Charles and an hour later the English HMS Warspite (64 cannons, 320 men) captured the Dutch Tholen (60 cannons, 296 men). However, since the English could not muster the necessary crew to occupy these ships, both were burned.

The fleets continued their south-easterly course during the night. In the morning the wind turned and blew from the southwest, which helped the Dutch ships to have a good trip. However, the persecution continued on the morning of August 5th. The badly damaged Zeven Provinciën was left with a small covering and was in danger of falling into the hands of the English. But these were not able to overtake them because there were not enough small but fast frigates available. The attack by an English fire was also repulsed. Eventually Admiral Banckert was able to form a new battle line of Dutch ships, which held up the English ships long enough to allow Admiral De Ruyter to land in his flagship. Shortly before noon, the units reached the Dutch coast at the mouth of the Scheldt , behind whose sandbanks they were safe from the deep English ships. On the night of August 6th, the Admiral Tromps squadron also arrived, which the English fleet was able to bypass under cover of darkness.

The loss of ships was astonishingly small. The English fleet had only lost the Resolution , while on the Dutch side only the Sneek and the Tholen were lost. The personnel losses were more serious, although today only estimates are possible. Prince Rupert and Admiral Monck officially stated that 1,000 to 1,200 English sailors would have died. Estimates for the Dutch fleet amount to a maximum of 2,500 men.

consequences

After their victory, the English fleet sailed along the Dutch coast and cut off all trade. Many English captains now set out to pillage places along the coast and take booty. The most famous case occurred on August 10th July. / August 20, 1666 greg. . Vice Admiral Robert Holmes (1622-1692) burned the village of Ter Schelling (today's West-Terschelling ) on the island of Terschelling and sank in the Vlie (near the island of Terschelling) 140 to 150 merchant ships that were anchored there. This event became known and celebrated in England as Holmes's Bonfire . Then the English fleet withdrew to its own waters.

In the Netherlands, the defeat sparked a political crisis. The ships from Zeeland and Friesland had suffered the greatest losses in Admiral Evertsen's vanguard squadron. Their envoys blamed Admiral de Ruyter's allegedly faulty leadership. The representatives of the city of Rotterdam , from which Admiral Tromp came, also accused De Ruyter, while his supporters accused Tromp of being a sympathizer of the Orange and traitors. The dispute took on such proportions that seafarers from the various officers in Vlissingen even fought open street battles. At the end of the dispute, on August 13, 1666, Admiral Tromp was released from the fleet.

The St. James's Day Fight was the last great naval battle of the Anglo-Dutch War. The rest of the year 1666 spent the opposing fleets with various maneuvers without major fighting. The Great Fire of London on September 2 also weighed heavily on the English war effort; the following year, scarcity of money prevented the Royal Navy from leaving. Much of their ships fell in June 1667 an attack of the Dutch fleet over the Thames Estuary victim ( → Raid on the Medway ), and then on July 21 jul. / July 31, 1667 greg. the war ended with the conclusion of the Peace of Breda .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail , Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, p. 332.

- ↑ a b c Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail , Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, p. 341.

- ↑ For the "Vier-Tage-Kampf" see: Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail , Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996.

- ↑ James R. Jones: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the Seventeenth Century , London / New York 1996, pp. 170f.

- ↑ The list of ships only corresponds to the order of battle in the case of the First Squadron. The Second Squadron is named first because it formed the vanguard. Other brands are marked with "fs"; Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail , Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, p. 384ff.

- ↑ The fleet of the Netherlands consisted of contingents of different admiralty, which are marked as follows: Maas (M), Amsterdam (A), Noorderkwartier (N), Zeeland (Z), Friesland (F). Maas, Amsterdam and Noorderquartier belong to the province of Holland, Zeeland and Friesland to the provinces of the same name.

- ^ Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail , Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, p. 331.

- ^ Robert Rebitsch: Rupert of the Palatinate. A German prince's son in the service of the Stuarts , Innsbruck / Wien / Bozen 2005, p. 108.

- ^ Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail , Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, p. 379ff.

- ↑ In the English fleet there were ships of first class (80 to 100 cannons), second class (60 to 80 cannons), third class (54 to 64 cannons), fourth class (34 to 54 cannons), fifth class (24 to 34 Cannons) and the frigates as sixth class. "M" stands for "Merchant", a converted merchant ship. Brander are abbreviated with "fs" for "Fire Ship"; a "*" indicates that this fire has been used. See Roger Hainsworth, Christine Churchers: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652-1674 , Stroud 1998, pp. 110f.

- ^ Roger Hainsworth / Christine Churchers: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652-1674 , Gloucestershire 1998, p. 150.

- ^ Charles Ralph Boxer: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th Century , London 1974, p. 34.

- ^ Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail , Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, p. 334.

- ^ Roger Hainsworth, Christine Churchers: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652-1674 , Gloucestershire 1998, p. 151.

- ^ Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail , Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, p. 335.

- ^ A b Roger Hainsworth, Christine Churchers: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652-1674 , Gloucestershire 1998, p. 152.

- ^ Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail , Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, p. 336.

- ↑ a b c Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail , Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, p. 337f.

- ^ Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail , Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, p. 340.

- ^ Charles Ralph Boxer: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th Century , London 1974, p. 36.

- ↑ James R. Jones: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the Seventeenth Century , London / New York 1996, pp. 171f.

literature

- Charles Ralph Boxer: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th Century . Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1974.

- Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail . Press of Sail Publications, Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, ISBN 0-948864-29-X .

- Roger Hainsworth, Christine Churchers: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652–1674 . Sutton Publishing Limited, Thrupp / Stroud / Gloucestershire 1998, ISBN 0-7509-1787-3 .

- Cyril Hughes Hartmann: Clifford of the Cabal . William Heinemann Ltd., London 1937.

- James R. Jones: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the Seventeenth Century . Longman House, London / New York 1996, ISBN 0-582-05631-4 .

- Richard Lawrence Ollard: Cromwell's Earl - A Life of Edward Mountagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich . HarperCollins Publishers, London 1994, ISBN 0-00-255003-2 .

- Robert Rebitsch : Rupert of the Palatinate. A German prince's son in the service of the Stuarts . Studien-Verlag, Innsbruck / Vienna / Bozen 2005, ISBN 3-7065-4143-2 (= supplement 1 of the Innsbruck Historical Studies ).