Robbery at the Medway

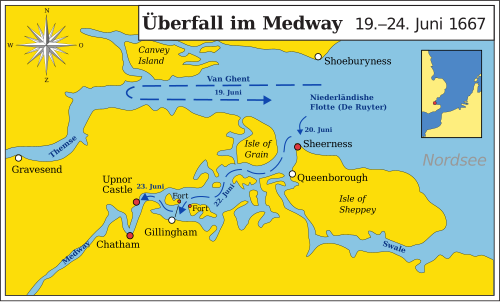

The raid in the Medway (also Battle of Chatham ; English Raid on the Medway , Dutch Tocht naar Chatham ) from June 19 to June 24, 1667 was a military operation of the Dutch fleet during the Anglo-Dutch War (1665-1667). Under the command of Admiral Michiel de Ruyter , Dutch ships entered the River Medway via the Thames estuary and captured or burned a large number of British Royal Navy warships there . This Dutch success made a major contribution to the conclusion of the Peace of Breda on July 31, 1667.

prehistory

( Note: Calendar dates in this article refer to the Gregorian calendar , which was ten days ahead of the Julian calendar used in England at the time .)

General development

After the end of the first Anglo-Dutch War in 1654, the monarchy was restored in England with the return of King Charles II (1630–1685). He needed financial means for a government independent of parliament , which he hoped to win through the booty in another war against the United Netherlands . In doing so, he was supported by the ambitions of the Royal African Company to harm Dutch competition. In the spring of 1665 there was an open war. After the first fighting, the Dutch won the four-day battle in June 1666 and believed they had won the upper hand. A few weeks later, however, the English fleet regained naval control in the North Sea in the “ St. James's Day Fight ” . As a result, the Royal Navy cut off Dutch shipping and English captains raided places along the coast. The most famous case occurred on August 20, 1666, when Vice Admiral Robert Holmes (1622-1692) burned down the village of Ter Schelling on the island of Terschelling and sank 140 to 150 merchant ships anchored there in the nearby Vlie . This event became known and celebrated in England as Holmes's Bonfire . Then the English fleet withdrew to its own waters.

War fatigue grew in the States General as the costs burdened the state budget and confidence in the ally France had waned. After the catastrophic losses of the merchant ships at Terschelling, the Dutch opened peace negotiations with Swedish mediation. But the English finances were also exhausted. The war had not brought in the hoped-for profits, and parliament refused to approve new funds for the conduct of the war after it was found that some of the funds granted had gone into the expensive royal household. Added to this were the losses caused by the severely impaired sea trade, the great plague epidemic of 1665 and the " Great Fire of London ". Against the resistance of Admiral Monck (1608–1670), King Charles II therefore ordered the large ships of the line to be dismantled and decommissioned in the winter of 1666/67 . The war should only be continued with pirates in order to damage Dutch trade.

In the meantime, the English envoys at the peace congress in Breda had been instructed to reach the most favorable conclusion possible. Against the background of the last successes in 1666, Charles II dragged out the negotiations in order to end the war at a profit, even though he had let his only leverage, the fleet, be rigged. The United Netherlands was not ready to make concessions. Soon, however, they came under pressure from other quarters. King Louis XIV of France (1638–1715) declared war on the Kingdom of Spain in May 1667 and began an invasion of the Spanish Netherlands in order to appropriate it (→ war of devolution ). The United Netherlands was now forced to bring the peace negotiations with England to an immediate conclusion so that they could concentrate on curbing French expansion plans. To this end, it seemed necessary to the council pensioner Johan de Witt (1625–1672), the head of Dutch politics, to increase the pressure on England by a direct attack on the island of Great Britain .

The Dutch expedition

The idea of landing troops in the British Isles was not new. Such plans had already been drawn up after the victory of the Dutch fleet in the four-day battle. In the summer of 1666, Admiral Michiel de Ruyter (1606–1676) had led about 6000 soldiers to the Thames estuary in addition to the fleet in order to be able to intervene in support of a local uprising of the English population against Charles II. But there was no such survey and the transport ships were sent back to the Dutch ports after a storm. Only a brief landing on the Isle of Thanet had been accomplished.

In the summer of 1667, Johan de Witt was well informed about the financial bottlenecks of the English crown through spies and also knew of the decommissioning of most of the English liners. Despite his own financial stress, he was now preparing the equipment of a Dutch expedition which received direct instructions to go up the Thames or the Medway and to destroy all ships and magazines at Rochester or Chatham, the centers of English naval power. The planned ship contingents were collected and prepared in various Dutch ports, while in April a squadron under Admiral Van Ghent tried to penetrate the Firth of Forth . This company served mainly to cover the main fleet, which gathered at the island of Texel in early June 1667 . Admiral de Ruyter sailed along its own coasts, taking on the various contingents. After all, his fleet consisted of 64 ships of the line and frigates , 15 fire engines , 7 escort ships and 13 Galiots with a total of 3330 cannons and about 17,500 men.

Course of operations

The Dutch fleet reached the English coast at Harwich on June 7, 1667. The following day they sailed south along the coast and anchored off the Thames estuary. They came into a storm that forced a large number of ships, their hawsers to cut and to drift. This mainly affected troop transport ships that were no longer available for the following operations. The next steps were discussed at a council of war on board the flagship . Admiral de Ruyter had reservations about sending the entire fleet up the river, as he was not exactly informed about the whereabouts of the smaller English naval units. Should these unexpectedly return and close the Thames estuary, the Dutch fleet would be trapped. Cornelis de Witt suggested that the main force itself should stay in front of the estuary and that a small detachment should monitor the English Channel , while a squadron under Admiral Willem Joseph van Ghent (1626–1672) should advance up the Thames. There this squadron was supposed to ambush some West Indian merchant ships at Gravesend , of which an intercepted Norwegian trader had reported. Admiral van Ghent's association consisted of 17 smaller warships, four Brandern , a few yachts and Galiots , as well as 1,000 marines under Colonel Dolman. The squadron left on the morning of June 19 and initially occupied Canvey Island . Then the wind changed, however, and the English merchant ships, which had meanwhile been warned of the approaching Dutch warships, escaped upriver.

The attack on Sheerness

Cornelis de Witt urged Admiral van Ghent to penetrate the Medway and attack the English fleet lying there. The access to this river was controlled by a fort which was still under construction at Sheerness on the Isle of Sheppey . To defend this key position, however, the English only had a weak Scottish crew, 16 guns, the small frigate Unity and two lightships. On June 20, Admiral van Ghent attacked the fort. The Unity only fired a single broadside and then fled up the Medway, pursued by a Dutch fire. The Dutch ships fired at the fort in the following two hours and eventually landed 800 navy soldiers under Colonel Dolman. The occupation fled without any serious resistance to the landing forces, and the entire Isle of Sheppey was occupied by Van Ghent's forces. The fight for this important position cost the Dutch about 50 men. The value of the captured 15 cannons and other goods was, according to contemporary estimates, 400,000 livres or four tons of gold.

English defense measures

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle (1608-1670), who was informed of the events on June 19, received the royal order to organize the defense. Monck first inspected the facilities on the Thames at the Fort of Gravesend and went to Chatham on the Medway on the morning of June 21 . There he found almost no organized defense. An iron chain had been pulled across the river at Gillingham , but it was too deep. Only three smaller ships were available to protect them: the Unity , the Charles V and the Matthias . Otherwise there was panic. Almost all of the more than 800 dock workers had fled. Of thirty boats and ships, only ten could be found because refugees had used them to escape or the local officials had their personal effects evacuated on them. The duke ordered the soldiers and officers he had brought with him to set up two coastal batteries on the bank near the chain, but even for this the necessary tools were missing. In order to create further obstacles in front of the chain, Admiral Monck ordered lightships to be sunk there. Two ships, the Norway Merchant and the Marmaduke , were successfully sunk, but the large Sancta Maria , which had also been designated as an obstacle, ran aground. The large warship Royal Charles was also on site, but it was completely unarmed. Admiral Monck ordered them to be brought upstream to safety, but there was no staff for that. When the Dutch attack later took place, she was still unmanned on the bank. There were hardly any volunteers among the more than 1,100 workers in the docks at Chatham. Because the king lacked the financial means, their pay was months in arrears, and now they refused to serve.

Breakthrough at Gillingham

On the morning of June 22nd, the Dutch associations began their advance in the Medway. The narrowness of the canal forced the ships to sail one behind the other in a line. In the lead, the Vrede drove under the command of its captain Jan van Brakel. The captain had been arrested two days earlier for having his men pillaged on the Isle of Sheppey. In order to restore his reputation, he had now voluntarily taken over the top position. Brakel's ship soon came under the crossfire of the three English defense ships and the two coastal batteries. However, without firing, he headed straight for the Unity and broadside it at the shortest possible distance. The English crew then fled the ship and left it to the Dutch. Under the protection of the powder smoke, the two following fires came up under Brakel's command and sank the English ships Charles V and Matthias in quick succession . The iron chain was then broken during the first ramming attempt. The Dutch ships now had free travel up the Medway, because behind the chain there was a wide gap between the sunk English ships, which was actually supposed to be closed by the sinking of the Sancta Maria . The fire of the following Dutch frigates soon silenced the English coastal batteries, the fire of which had remained almost ineffective due to structural defects. As the biggest booty of the day, the Dutch fleet fell into the hands of the Royal Charles, one of the largest English warships, which had often served as the flagship of the English naval commanders.

Raid at Upnor Castle

- Andrew Marvell (1667)

|

The English were now making defensive preparations at Upnor Castle . The Duke of Albemarle and the commander of the docks, Peter Pett, put the castle's guns in readiness for action and had another battery of guns thrown on the other bank. Tensioning another chain across the river failed. They wanted to start moving the warships in the direction of Chatham, but again the crews were missing. In order to at least protect the largest warships from being captured, the Duke of Albemarle ordered them to be sunk in shallow water, where they could later be raised again.

In the late afternoon of June 22nd, the Dutch advance was halted by the tide. Van Ghent, De Ruyter and De Witt met on board the captured Royal Charles to discuss how to proceed. These three commanders decided to advance further upstream the following day and attack the Chatham Dockyards and the large warships located there. On June 23, around noon, the remaining Dutch fires, protected by four frigates and a large number of smaller ships, attacked the English positions. They soon got caught in the crossfire between Upnor Castle and the battery hastily thrown up on the opposite bank of the river. A detachment of Navy soldiers landed and went on to attack the English ammunition magazine at Upnor Castle, which they successfully blew up before retreating.

In the meantime, the Dutch ships were firing at the English gun batteries. During the fight there was still no wind, which De Ruyter and other officers forced to transfer to long boats in order to direct the actions of their units from these. After a fierce fire fight, the Dutch fires succeeded in attacking the three large warships Loyal London (92 cannons), Royal Oak (76 cannons) and Royal James (82 cannons) lying on the bank . The water in which these ships had been sunk by the English themselves was not shallow enough to offer protection against a fire attack. All three ships fell victim to the Dutch fire after their hull crews had fled. The Duke of Albemarle, meanwhile, tried to drag the remaining warships upstream under the protection of the guns of Chatham. He lined up battle-ready warships on the banks and gathered militia troops to stop the Dutch advance. In fact, the Dutch ships did not go any further against the stiffening English resistance. In the late afternoon they retreated as far as Gillingham with the incoming tide. There they made the conquered English ships Royal Charles and Unity seaworthy and left the Medway on June 24th. The losses from the battle in front of Upnor Castle amounted to about 500 men on the English side, while 50 to 150 men were assumed on the Dutch side.

consequences

The Dutch attack on the English ships in the Medway turned into the greatest debacle of the war for the Royal Navy. She lost more ships than in all previous sea battles combined. The Royal Charles and the Unity had been conquered by the Dutch and the Loyal London , Royal James , Royal Oak , Charles V , Matthias , Marmaduke , Sancta Maria and five other lightships, two ketches , a flute and a smaller ship were sunk or burned. In contrast, the Dutch had deployed a total of ten fire engines. There were also other indirect losses by the Royal Navy. The Vanguard, for example, was aborted while trying to set it on the ground and finally had an accident at Rochester in such a way that it could no longer be lifted. Further north, Prince Rupert had wanted to close the Thames on the other side of Gravesend for a possible Dutch advance by sinking the Golden Phoenix , House of Sweeds , Welcome and Leicester there . It turned out that this was a total waste of important warships, as the Dutch never advanced beyond Gravesend. Overall, these losses - especially those of the three large warships - changed the strategic balance between England and the United Netherlands for years in favor of the Dutch.

After this success, the Dutch were able to demonstrate their absolute superiority. Part of the Dutch fleet took action against the English merchant ships on the English Channel coast, while another under Admiral Van Nes continued to block the Thames for English shipping. In the following weeks, in smaller operations, Dutch troops landed in some places or sailed warships up the Thames.

In London, the events on the banks of the Medway caused a severe economic slump and panic among the population. Rumors said Chatham was on fire, as were Gravesend, Harwich , Queenborough , Colchester and Dover. There were reports of Dutch landings at Portsmouth , Plymouth and Dartmouth , and it was even alleged that the King had fled; the papists are about to take power. Even an imminent French landing was expected.

The Dutch had taken a position in the Thames by which they cut off London from trade. The coal deliveries from Tyne in particular failed, and the coal price soon increased tenfold. The English fleet was weakened by the raid and there was little money to replenish it. King Charles II therefore had little choice but to give instructions to his emissaries at the peace conference in Breda to conclude the treaty as soon as possible. The signing of the Peace of Breda took place on July 31, 1667. On August 26, the Dutch fleet abandoned the blockade of the English ports and the Thames estuary in accordance with the treaty.

reception

- Rudyard Kipling (1911)

|

In the Netherlands, the States General had received daily letters from Cornelis de Witt about the progress of the operations. On June 27th, news of the victory finally reached the city of Breda, where a thanksgiving service was celebrated in all churches. The reports were printed and sent to the various provinces with the request to hold a “solemn Danck and Prayer Day” in all churches across the country on July 6th. On the evening of that day bonfires were lit, church bells were rung and gun salutes were fired. In the weeks that followed, copperplate engravings such as those by Romeyn de Hooghe (1645–1708), which illustrated the events in the Medway on the basis of the published reports, soon circulated . This was followed by paintings by well-known artists such as Willem Schellinks (1627–1678) and Pieter Cornelisz van Soest after a few months . Cornelis de Witt himself gave at Jan de Baen (1633-1702), a portrait of himself in order, that would portray him as the winner of the Battle of the Medway (→ see above) . The painting was completed in the same year and hung in Dordrecht's town hall .

The conquered Royal Charles was on public display in Hellevoetsluis . Groups of visitors, including foreign princes, visited the former flagship, which bore the name of the English king. Charles II protested against this as he saw this as a form of insult. At the beginning of the following Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674), he cited these facts as a reason for war. The ship was auctioned in 1673 and then dismantled. However, the metal tail section with the English royal insignia was kept and is now in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam .

On the English side, attempts were initially made in some publications such as the London Gazette to downplay the extent of the defeat, but, as contemporary reports show, this hardly succeeded. Samuel Pepys was already well informed of the losses. In his diary he described the extent of the panic that had broken out in London and saw the cause of the catastrophe in the underpayment of English seamen. The English poet Andrew Marvell (1621–1678) took the defeat in September 1667 as an occasion for a biting satire in his poem “Last Instructions to a Painter” (→ see above). Also Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) the subject in 1911 resorted to in the poem "The Dutch on the Medway," in which he blamed mainly King Charles II and its extravagance for the disaster (→ see: pull-out box right)..

The history largely corresponds to the assessment of the English defeat. The historian George Franks ruled in 1942 that the Medway disaster was "the worst defeat for the Royal Navy that it has ever suffered in its home waters." In 1949, Alvin Coox spoke of "a festering national humiliation". The German naval historian Otto Groos shared this assessment in 1930: "Never in its entire history" England had "been so humiliated." British historian Charles Ralph Boxer saw 1974 in the Raid on the Medway alongside the battle of Majuba Hill in 1881 and the fall of Singapore 1942 one of Britain's most humiliating defeats.

The attack on the Medway relativizes the claim, sometimes rumored in British historiography, that after William the Conqueror there was never an invasion of Great Britain.

Individual evidence

- ^ Charles Ralph Boxer: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th Century. London 1974, p. 36.

- ^ Alvin Coox: The Dutch Invasion of England 1667. In: Military Affairs. Volume 13, 1949, No. 4, p. 223.

- ^ Kurt Kluxen : History of England. From the beginning to the present (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 374). 4th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-520-37404-8 , p. 350.

- ^ Alfred Thayer Mahan : The Influence of Sea Power on History 1660-1812 . Herford 1967, p. 48.

- ^ Alvin Coox: The Dutch Invasion of England 1667. In: Military Affairs. Volume 13, 1949, No. 4, p. 224 f; Alexander Meurer : History of naval warfare in outline. Leipzig 1942, p. 204.

- ↑ James R. Jones: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the Seventeenth Century. London / New York 1996, pp. 170 f .; Alvin Coox: The Dutch Invasion of England 1667. In: Military Affairs. Volume 13, 1949, No. 4, p. 224.

- ^ Alvin Coox: The Dutch Invasion of England 1667. In: Military Affairs. Volume 13, 1949, No. 4, p. 225.

- ^ Alvin Coox: The Dutch Invasion of England 1667. In: Military Affairs. Volume 13, 1949, No. 4, p. 226.

- ^ A b Alvin Coox: The Dutch Invasion of England 1667. In: Military Affairs. Volume 13, 1949, No. 4, p. 228.

- ^ Roger Hainsworth, Christine Churchers: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652-1674. Sutton Publishing Limited, Thrupp / Stroud / Gloucestershire 1998, p. 160.

- ^ Roger Hainsworth, Christine Churchers: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652-1674. Sutton Publishing Limited, Thrupp / Stroud / Gloucestershire 1998, p. 160; Alvin Coox: The Dutch Invasion of England 1667. In: Military Affairs. Volume 13, 1949, No. 4, p. 228.

- ^ Roger Hainsworth, Christine Churchers: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652-1674. Sutton Publishing Limited, Thrupp / Stroud / Gloucestershire 1998, p. 160 f.

- ^ A b c Alvin Coox: The Dutch Invasion of England 1667. In: Military Affairs. Volume 13, 1949, No. 4, p. 229.

- ^ A b c Roger Hainsworth, Christine Churchers: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652–1674. Thrupp / Stroud / Gloucestershire 1998, p. 161.

- ^ Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail. Press of Sail Publications, Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, p. 346 f.

- ↑ Analogous translation: “Every sad day new losses: The Loyal London burns a third time; And the faithful Royal Oak and Royal James ; United in fate, enlarge the fire with their own flames; Our navy shouldn't survive any; But the ships themselves were taught to dive; And the friendly river hid them in its course; Filled her keel with the muddy tide. ”See Andrew Marvell: Last Instructions to a Painter. September 4, 1667.

- ^ A b Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail. Press of Sail Publications, Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, p. 347.

- ↑ On board the Royal Oak , the Scottish Captain Archibald Douglas refused to leave his post and burned with the ship. See Charles Ralph Boxer: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th Century. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1974, p. 39.

- ^ A b Roger Hainsworth, Christine Churchers: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652–1674. Sutton Publishing Limited, Thrupp / Stroud / Gloucestershire 1998, p. 163.

- ↑ Contemporary information from Chatham employee Edward Gregory. Reprinted in: Roger Hainsworth, Christine Churchers: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652–1674. Sutton Publishing Limited, Thrupp / Stroud / Gloucestershire 1998, p. 163.

- ^ Alvin Coox: The Dutch Invasion of England 1667. In: Military Affairs. Volume 13, 1949, No. 4, p. 230.

- ↑ James R. Jones: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the Seventeenth Century. Longman House, London / New York 1996, p. 178.

- ↑ Analogous translation: “The money that should feed us; Did you spend for your pleasure; Then how can you have sailors; To help you in battle; Our fish and cheese are rotten; What increases the scurvy; We cannot serve you when we starve; And the Dutch know this; The ships in every port; Be it whole or healthy; And, when we try to seal a leak; No tow can be found; And when it comes to the caulkers; And the carpenters too; They ran away without pay; And the Dutch know this; Just powder, cannons and bullets; We can hardly find it; Their award was given out in conviviality; And at festivals in Whitehall; While we in ragged doublets; Queuing from the ship to the shop to beg friends for leftovers; And the Dutch know this! ”See Rudyard Kipling: The Dutch in the Medway. In: Songs Written for CRL Fletcher's "A History of England". 1911, E-Text .

- ↑ Theatrum Europaeum , Volume 10, pp. 618 and 627.

- ^ Roger Hainsworth / Christine Churchers: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652–1674 , Thrupp / Stroud / Gloucestershire 1998, p. 166 f.

- ^ Brian Lavery: The Ship of the Line. Volume 1, Conway Maritime Press, 2003, p. 160.

- ↑ Samuel Pepys' diary, June 1667 in Wikisource (English).

- ^ Andrew Marvell: Last Instructions to a Painter. In: TheOtherPages.org , September 4, 1667.

- ^ Rudyard Kipling: The Dutch in the Medway. In: Songs Written for CRL Fletcher's "A History of England". 1911.

- ^ "The most serious defeat it has ever had in its home waters." See H. George Franks: Holland Afloat. London 1942, p. 98.

- ↑ "a rankling national humiliation". See Alvin Coox: The Dutch Invasion of England 1667. In: Military Affairs. Volume 13, 1949, No. 4, p. 223.

- ↑ Otto Groos: Ruyter. In: Friedrich von Cochenhausen (Hrsg.): Führertum - 25 life pictures of generals of all times. ES Mittler & Sohn, Berlin 1930, p. 165.

- ^ Charles Ralph Boxer: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th Century. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1974, p. 39.

Web links

- The Dutch in the Medway ( Memento from October 21, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). In: Deruyter.org (English, also as PDF )

- The Dockyard story - Pepys. In: Sheerness Dockyard Preservation Trust , 2017 (English)

literature

- Charles Ralph Boxer : The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th Century. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1974.

- Alvin Coox : The Dutch Invasion of England 1667. In: Military Affairs . Volume 13, 1949, No. 4, pp. 223-233.

- Frank L. Fox: A distant Storm - The Four Days' Battle of 1666, the greatest sea fight of the age of sail. Press of Sail Publications, Rotherfield / East Sussex 1996, ISBN 0-948864-29-X .

- Roger Hainsworth, Christine Churchers: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652–1674. Sutton Publishing Limited, Thrupp / Stroud / Gloucestershire 1998, ISBN 0-7509-1787-3 .

- James R. Jones: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the Seventeenth Century. Longman House, London / New York 1996, ISBN 0-582-05631-4 .

- Brian Lavery: The Ship of the Line. Volume 1, Conway Maritime Press, 2003, ISBN 0-85177-252-8 .

- Charles Macfarlane: The Dutch on the Medway. James Clarke & Co., London 1897 (digitized version) .

- NAM Rodger : The Command of the Ocean. A Naval History of Britain 1649-1815. WW Norton & Company, New York 2004, ISBN 0393328473 .

- PG Rogers: The Dutch on the Medway. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1970, ISBN 0-19215185-1 .