Thames tunnel

The Thames Tunnel , dt. Themsetunnel , crosses under the Thames in London and connects the districts of Rotherhithe and Wapping with each other. The tunnel is about 10 meters wide and 366 meters long. It was completed in 1843 and was the world's first tunnel under a river. The responsible engineers were Marc Isambard Brunel and his son Isambard Kingdom Brunel . Originally planned for horse-drawn carriages, the tunnel was never used in this way, but first for pedestrians and then for railways. Until 2007 the underground trains of the East London Line , which belonged to the London Underground , ran here. Trains on the London Overground have been running through it since 2010 .

history

First projects

At the beginning of the 19th century the need for a new transport link from the north to the south bank of the Thames grew to connect the expanding docks on both sides of the river. In 1799, engineer Ralph Dodd made an unsuccessful attempt to build a tunnel between Gravesend and Tilbury .

Between 1805 and 1809 a group of Cornish miners , including Richard Trevithick , tried to build a tunnel further upriver between Rotherhithe and Wapping. The project failed due to the difficult soil conditions. The miners were used to hard rock and had not adapted their building methods to the soft clay and quicksand. The Thames Archway project was discontinued after 305 meters of a total of 366 planned meters had been dug. Even if completed, the usefulness of the tunnel would have been questionable given a width of just 2-3 feet (61-91 cm) and a height of 5 feet (1.52 m).

The failure of the project led engineers to believe that a tunnel under a body of water was not feasible. The French engineer Marc Isambard Brunel was not convinced of this. In 1814 he presented the Russian Tsar Alexander I with a plan to tunnel under the Neva in Saint Petersburg . Although the plan was abandoned in favor of a bridge, Brunel continued to develop his new tunneling methods.

Construction work

Brunel and Thomas Cochrane patented the tunnel boring shield in January 1818 , a significant advance in tunneling. In 1823 Brunel drafted a plan for a tunnel between Rotherhithe and Wapping using his new tunneling method. Various investors, including Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington , financed the project. The Thames Tunnel Company was founded in 1824, and construction work began in February 1825.

The first step was the construction of a large shaft on the south bank at Rotherhithe, 150 feet (46 m) from the river bank. For this purpose, an iron ring with a diameter of 50 feet (15.24 m) was put together. A brick wall 40 feet (12.19 m) high and 3 feet (91 cm) thick was built above it. On top of it stood a powerful steam engine that drove the pumps. The whole apparatus weighed around 1000 tons. Below the sharp lower edge of the ring, the workers removed the earth by hand. The whole shaft gradually sank under its own weight to the desired depth. The shaft was completed in November and the tunneling work could begin.

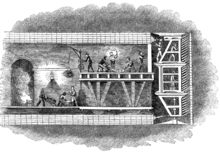

The tunnel boring shield , built in the southern London borough of Lambeth and assembled in the Rotherhithe shaft, was the key element in the construction, as it could be used to support the broken walls. However, many workers, including Brunel, fell ill from polluted water that dripped from the river through the tunnel ceiling. When chief engineer William Armstrong fell ill in April 1826, Isambard Kingdom Brunel , Marc's son, only 20 years old, took over management.

The construction work proceeded slowly, about 3 to 4 meters per week. In order to earn some money, the tunnel company allowed a tour of the construction site. Around 600 to 800 visitors per day paid one shilling for it . On January 18, 1827, by now 549 feet (167 m) had been dug, the tunnel was suddenly flooded. Isambard Kingdom Brunel had a diving bell lowered from a boat to repair the hole in the river bed by stuffing the opening with sacks filled with clay. After the repairs and drainage of the tunnel, Brunel held a banquet in it.

On January 12, 1828, the tunnel was flooded again. Six workers died, and Isambard Kingdom Brunel almost drowned. Due to financial problems of the tunnel company, the tunnel was bricked up in August. The project was dormant for seven years until Marc Brunel raised sufficient funding, including a £ 247,000 loan from the Treasury. Work was resumed in February 1836 and a new tunnel boring shield had to be installed. Renewed floods as well as fires and leaks in the hydrogen sulfide and methane tanks delayed the completion of the project further and further.

The tunnel construction work could not be completed until November 1841. The tunnel was then equipped with lighting, a street and spiral stairs. A machine house with the drainage machine was built on the south side. Finally, the tunnel was opened on March 25, 1843.

Pedestrian tunnel

The Thames Tunnel, a triumph of engineering, did not prove to be a financial success. The pure construction costs were £ 454,000, the equipment a further £ 180,000, well above the initial cost estimates. The proposal to widen the entrance to allow use by wagons failed because of the costs. The tunnel was only used by pedestrians. The Thames Tunnel became a tourist attraction with around two million visitors a year who each paid a penny to go through. He was sung about in numerous folk songs. However, Karl Baedeker Jr. pointed out in his first London Guide of 1862 that the annual income of around £ 5,000 was barely enough to cover the repair costs caused by the leakage of spring water. The American traveler William Allen Drew wrote: "Nobody goes to London without seeing the tunnel." He called the tunnel the "eighth wonder of the world" and described it effusively. As a result, the tunnel attracted many prostitutes who waited there for customers. Pickpockets hid behind the arches to steal from passers-by.

Railway tunnel

Constantly in financial trouble, the Tunnel Company sold it to the East London Railway in November 1865 . The consortium consisting of six railway companies intended to use the tunnel as part of a connection for goods and passengers between Wapping (later Liverpool Street ) and the South London Line . The generous clearance profile provided enough space for trains. The first train ran on December 7, 1869. In 1884, the no longer used entrance shafts were converted into the Wapping and Rotherhithe stations . The East London Railway later went on in the London Underground. Freight trains also ran on the route until 1962.

On March 25, 1995, the tunnel was closed for a long time to carry out renovation work. Its condition had become so bad that London Underground announced that it would have to shut down the East London Line for good if the tunnel could not be repaired again. The proposed method, spraying concrete, led to disputes with initiatives that wanted to keep the tunnel in its original state and questioned the necessity of the work.

The parties to the dispute agreed to leave a short section at both ends in the original state and to treat the rest of the tunnel more gently. The tunnel reopened on March 25, 1998, much later than originally planned. From December 22, 2007, the route was closed again due to construction work for an extension of the East London Line. Since reopening on April 27, 2010, this line has been part of the London Overground network .

meaning

The construction of the Thames Tunnel had proven that, despite the skepticism of numerous engineers, it was actually possible to build underwater tunnels. In the following decades other structures of this type were built in the UK; the Tower Subway in London, the Severn Tunnel under the Severn and the Mersey Railway Tunnel under the River Mersey . All of them came about with further developments of Brunel's tunnel boring shield , with James Henry Greathead in particular excelling in this area. The historic importance of the tunnel was recognized when it was added to the list of Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks by the American Society of Civil Engineers in 1991 and the structure was listed on March 24, 1995. A plaque in the Rotherhithe train station commemorates the achievements of the two Brunels.

Brunel Engine House

The Brunel Engine House is located in Rotherhithe, the machine house designed by Marc Isambard Brunel. It once housed the pumping machines and was saved from disintegration in 1975. Today the building serves as a museum that informs visitors about the construction of the tunnel. A steam engine that was installed a little later and donated by the Royal Navy is on display . The museum organizes tunnel tours several times a year.

See also

Magazine articles

- The opening of the Thames tunnel . In: Illustrirte Zeitung . No. 1 . J. J. Weber, Leipzig July 1, 1843, p. 5-7 ( Wikisource ). .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c John Timbs: Stories of Inventors and Discoverers in Science and the Useful Arts. Kent 1860, p. 287.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Denis Smith: Civil Engineering Heritage - London and the Thames Valley. Thomas Telford, London 2001, ISBN 0-7277-2876-8 , p. 17.

- ↑ Nathan Aaseng: Construction - Building the Impossible. The Oliver Press, Minneapolis 1999, ISBN 1-881508-59-5 , p. 28.

- ↑ Karl Baedeker: London and its surroundings, along with travel routes from the Continent to England and back. Guide for travelers. Baedeker, Koblenz 1862, p. 83.

- ^ William Allen Drew: Glimpses and Gatherings During a Voyage and Visit to London and the Great Exhibition in the Summer of 1851. Homan & Manley, 1852, pp. 242-249.

|

Upstream Tower Bridge |

River crossings of the Thames |

downstream Rotherhithe tunnel |

Coordinates: 51 ° 30 ′ 11 ″ N , 0 ° 3 ′ 16 ″ W.