Marc Isambard Brunel

Sir Marc Isambard Brunel (born April 25, 1769 in Hacqueville , Normandy (today in the Eure department ), † December 12, 1849 in London ) was a Franco-British engineer , architect and inventor . He built the first tunnel under the Thames and was the father of the railroad and ship engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel .

Life

Childhood and youth

Brunel was born in Hacqueville near Gisors in Normandy, where his family had built land for generations. His parents chose him for a career in the church and at the age of eight he was sent to the college in Gisors in order to acquire the necessary humanistic education. Brunel, however, showed little inclination towards the classical subjects, but was more interested in mechanics and drawing even at this age. At the age of eleven he entered the Saint-Nicaise seminary in Rouen and made the decision to qualify for admission to the Navy. After he had occupied himself with drawing and hydrography for some time , he received a position on the corvette named after him from the Navy Minister Charles-Eugène-Gabriel de La Croix, marquis de Castries , on which he stayed for the next six years. At the beginning of his first trip to the West Indies , he constructed a quadrant so precise that he used it throughout his time as a seaman.

In 1792 the ship was dismissed and Brunel went to Paris at the beginning of 1793 , but soon had to leave the city again because of his openly expressed royalist attitude. He returned to Rouen, but was also at risk here and got a passport to America. He left revolutionary France on July 7th and arrived in New York on September 6th, 1793 .

Emigrant in America

In America, Brunel finally decided on a technical profession. He first got a job surveying a large piece of land on Lake Ontario and then surveying a planned canal between the Hudson River and Lake Champlain. The management of the surveying team was initially in the hands of another French émigré, but was then transferred to Brunel as the technical difficulties increased.

After a few more orders, Brunel won the competition to design a new town hall in Washington against several professional architects, even if his design was not implemented for cost reasons. He was also selected to design the Bowery Theater in New York and also directed its construction. The theater burned down in 1821.

Brunel has now been appointed chief architect of the city of New York and was commissioned to build an arsenal and a cannon foundry. After he had worked out a plan for the mechanized fabrication of ship blocks on a large scale, he left for England on January 20, 1799 to present his plans to the British government.

Engineer, architect and inventor in England

Arrived in England in March, he married Sophia Kingdom a short time later, whom he had met while in France.

In May 1799, Brunel received his first patent for a writing and drawing instrument in the manner of a pantograph and at around the same time constructed a machine for the production of cotton thread, which was often used in the factories, but which Brunel made no profit because he failed to do so had to have the invention patented. He made a few other ingenious inventions of lesser importance, none of which, apart from the recognition of his technical skills, brought him any material gain. He secured the cooperation of Henry Maudslay in good time for the construction of a saw frame for the efficient production of rope blocks and received a patent for it in 1801 after the drawings and the functional models had been completed.

Brunel presented his plans to the Admiralty , which passed them on to Sir Samuel Bentham , Inspector General of Naval Factories. After long negotiations and delays, Brunel's plans were finally accepted in May 1803 and he was commissioned to assemble his machines at the Portsmouth naval yard , which was completed in 1806. The system consisted of 43 individual machines that performed the various manufacturing processes for the production of rope blocks, which were previously made by hand. With the help of the machines, ten workers were able to do the same work that previously required 100 craftsmen. The rope plugs were of better quality than the handcrafted ones and the financial savings were enormous, estimated at £ 24,000 a year. Brunel had gone to great lengths to carry out his plans, but the government's approval of his claims was slow. He eventually received £ 17,000 in compensation.

From 1805 and 1812 Brunel was then mainly occupied with designing and improving machines for timber production. He built several sawmills in Battersea at his own expense and in 1811 received a government contract to set up sawmills and other machinery in Woolwich .

In the years that followed, he made large-scale woodworking improvements at the Chatham Naval Yard and built an iron rail line to move the timber from one end of the shipyard to the other. He also built a shoe factory for the army. But since the war ended in 1815, Brunel suffered a great financial loss.

In 1812 Brunel made his first experiments with steam control on the Thames and advocated a steamship line between London and Margate . Two years later he suggested to the naval office that the sailors be towed out to sea with the help of tugboats and made experiments at his own expense to build seaworthy steamships of the appropriate size. But the naval office revoked its approval and the cost commitment after six months, because its attempts were considered "too fantastic" and impracticable. Brunel then received a few more patents for inventions of lesser importance, but none of them were successful because he lacked the necessary business acumen. B. 1816 a knitting machine. In 1820 he designed a bridge over the Seine near Rouen and a wooden bridge over the Neva near Saint Petersburg , but neither of them was built. His draft of a hurricane-proof bridge to the island of Bourbon, however, was accepted and carried out by the French government.

In 1814 Brunel's sawmills in Battersea had been almost completely destroyed by fire. From then on, the company's financial success went steadily downhill due to mismanagement until the crisis came in 1821 and Brunel was imprisoned for his debts. After a few months, on the intercession of several influential friends, he received £ 5,000 from the government to pay off his debt and was released.

During the next few years Brunel constructed sawmills for Trinidad and Berbice and made some improvements in marine steam engines and paddle wheels. In 1823 he drew up plans for swing bridges in the port of Liverpool and three years later introduced floating piers. He was asked for his opinion on many technical projects of the time, while he himself experimented with LPG engines, for which he sacrificed a lot of time and money. He also designed and patented a machine based on his principle, but had no practical success with it either, so the plan was eventually abandoned.

Tunnel under the Thames

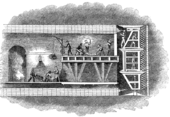

In the following years he devoted all of his energy to building the Thames Tunnel in London. In 1824, under the auspices of the Duke of Wellington, a society was founded with the aim of digging a tunnel under the Thames according to plans drawn up by Brunel from Rotherhithe to Wapping . Brunel suggested driving the tunnel to the full extent as a double archway instead of first creating a smaller gallery and then widening it. He wanted to use a design that he had patented together with Thomas Cochrane in 1818 . This construction consisted of a large tunnel boring shield that covered the entire excavation site. The shield consisted of 12 separate frames that held 36 cells together, each with a miner working. The shield could be moved by a screw depending on the progress of the excavation.

Work began on February 16, 1825 in Rotherhithe and was not finished until 1842 due to significant technical problems. In 1827 there was a water ingress that could be contained with sacks of clay. In 1828 there was another flood and in August of that year work was stopped. The tunnel was walled up for seven years. After the resumption of work, there were three more water ingresses before the tunnel was finally opened to the public in March 1843. Brunel reacted to these setbacks with his own ingenuity and pursued the work with tireless energy, but eventually suffered a stroke and was partially paralyzed. But he recovered to the point that he could take part in the opening ceremony.

The tunnel construction had exhausted Brunel's strength to such an extent that he later largely withdrew from professional life. In 1845 he suffered another stroke and died four years later, on December 12, 1849, and was buried on the 17th of the month in Kensal Green Cemetery .

Honors

Brunel was elected a member of the Royal Society in 1814 and became its vice-president in 1832 under the presidency of the Duke of Sussex. In 1826 Brunel was elected to the Académie des Sciences and in 1834 to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences . On March 24, 1841, shortly before completion of the tunnel, he was beaten by Queen Victoria to Knight Bachelor ("Sir") in Buckingham Palace . He was a corresponding member of the Institut Française and received the Order of the Legion of Honor in 1829 . He was also a member of the Royal Academy in Stockholm and many other foreign scientific societies. In 1823 he became a member of the Institute of Civil Engineers , whose meetings he attended continuously and before which he gave many lectures. In 1839 he received the Telford Silver Medal for his report on the shield used in tunnel construction. In 1845 he was elected an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh .

In December 1827, when the literary association " Tunnel over the Spree " was founded in Berlin, Brunel was made an honorary member of the association, an award for which he politely thanked the Berlin writers in March 1828.

On March 21, 2011, Autodesk released a new version of Autodesk Inventor , in which Brunel's name was the inspiration for the company's internal name in his honor.

literature

- Paul Clements: Marc Isambard Brunel. 1970, ISBN 0-582-11003-3 .

- Brunel, Sir Marc Isambard . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . 11th edition. tape 4 : Bishārīn - Calgary . London 1910, p. 682–683 (English, full text [ Wikisource ]).

Web links

- Brunel Museum - The museum in Rotherhithe near London is in the building that originally housed the pumps for the Thames tunnel.

- Entry to Brunel; Sir; Marc Isambard (1769–1849) in the Archives of the Royal Society , London

- Article by / about Marc Isambard Brunel in the Polytechnisches Journal

Individual evidence

- ^ Directory of members since 1666: Letter B. Académie des sciences, accessed on September 29, 2019 (French).

- ^ William Arthur Shaw: The Knights of England. Volume 2, Sherratt and Hughes, London 1906, p. 343.

- ^ Fellows Directory. Biographical Index: Former RSE Fellows 1783–2002. Royal Society of Edinburgh, accessed October 13, 2019 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Brunel, Marc Isambard |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Franco-British engineer, architect and inventor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 25, 1769 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hacqueville , Normandy, today the Eure department |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 12, 1849 |

| Place of death | London |