Liverpool Street Station

The Liverpool Street station is one of the main stations of London and is located on the same street in the northeast corner of the City of London . It was opened in 1874 as the new terminus of the Great Eastern Railway and replaced the previous Bishopsgate station further east . The train station, located in the Travelcard tariff zone 1, is now mainly served by Abellio Greater Anglia trains. Trains operate to North East London, Essex and other regions of East England . Entrances are on Bishopsgate, Liverpool Street itself and the Broadgate Business Center (which was built on the site of the former Broad Street train station ). Liverpool Street is one of 18 train stations operated by the rail infrastructure company Network Rail . In 2016, 67.339 million rail passengers used the station, plus a further 71.61 million passengers on the subway. All in all, this results in over 380,000 people every day.

railroad

Operation and plant

Liverpool Street is the third busiest train station in London and the UK, after Waterloo and Victoria . Trains run from Liverpool Street to the east of England , including to Cambridge , Chelmsford , Clacton-on-Sea , Colchester , Harlow , Hertford , Ipswich , Norwich and Southend-on-Sea , as well as connections to the eastern boroughs of London. A few express trains daily to Harwich allow connections to the ferries to Hoek van Holland , the Stansted Express runs to London Stansted Airport .

Most of the trains that run from this station on the Great Eastern Main Line are operated by the Abellio Greater Anglia rail company . The local trains to Shenfield have been offered by TfL Rail since 2015 , as a preliminary operation for the S-Bahn-like Crossrail route, which will gradually open in 2018/19. London Overground operates suburban services on the Lea Valley Lines to Enfield Town, Cheshunt and Chingford. A small number of late evening and weekend trains are operated by c2c and run via Barking to Southend-on-Sea and Shoeburyness .

As is customary in the north of London, the station and the outgoing lines are electrified with AC overhead lines (25 kV / 50 Hz). Parts of the station, including the two westernmost platforms in the main hall and the subway signal box, are under monument protection ( Grade II ).

history

A new terminus for the city (1875)

The Great Eastern Railway (GER) was created in 1862 from the merger of several railway companies. They now owned Bishopsgate station in London, which served as the starting point for the routes to east England. Bishopsgate was inadequate for GER passenger traffic and, due to its location in the Shoreditch district, was not very attractive for commuter traffic to the City of London , to which the company had paid special attention. As a result, the GER planned a new, more centrally located train station.

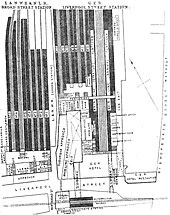

In 1865, the first plans were for a 1.6 km long line that branches off the main line east of the existing terminus in Shoreditch, and a new terminus on Liverpool Street. Bishopsgate was to serve as a freight yard after the project was completed. Liverpool Street was to be used by GER and the East London Railway (ELR). The station was to be two levels, with the GER platforms resting on brick viaducts and the ELR platforms about 37 feet (11.27 m) below. The station building was to be about 630 × 200 feet (192 × 61 meters) with the main facade on Liverpool Street and a side entrance on Bishopsgate Street (now part of the A10 as Bishopsgate ). The main wooden track hall of the station was to be in two parts, with a central cavity to let light through to the lower part and allow air to circulate. The GER architect designed a station building in the Italianate style .

The Parliament gave the Great Eastern Railway (Metropolitan Station and Railways) Act 1864 a license to build the track and the train station. The station was built on ten acres (four hectares ) of land that used to be the Bethlem Royal Hospital . At the same time, the North London Railway had Broad Street Station built on the adjacent property . The land was acquired through expropriation , which resulted in the loss of home to 3,000 residents of the parish of St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate. The 7,000-person rental apartments around Shoreditch were evicted to make way for the driveway to Liverpool Street; likewise the City of London Theater and the municipal gas works had to give way. In order to compensate for the plight of those affected by the deportation, the railway company was obliged by the law of 1864 to run inexpensive workers' trains to and from the station on a daily basis.

The station was designed by GER engineer Edward Wilson and built by the London construction company Lucas Brothers . The Fairburn Engineering Company was responsible for designing and building the roof . The architectural style was almost neo-Gothic , building materials were mainly bricks , while Bath Stone was available for the decorative elements . The building had ticket offices as well as the offices of the GER, including rooms for the chairman, the board of directors, the supervisory board, the secretariat and the engineers. Four wrought-iron, glazed gable roofs spanned the main hall. The two central roofs were 109 feet (33.22 m) wide, the outer 46 and 44 feet (14.02 and 13.41 m) wide. The length of the roofs was 730 feet (220.5 m) over the east main line platforms and 450 feet (137.16 m) over the western suburban line platforms. The station had ten platforms, two of which were reserved for the main lines and the rest for local traffic.

Local trains began to use the partially completed station on October 2, 1874. From November 1, 1875, it was fully operational. The original Bishopsgate terminus was closed to passenger traffic and served as a freight station from 1881 until it fell victim to a major fire in 1964. Designed by Charles Barry Jr., the Great Eastern Hotel just south of Liverpool Street Station opened in May 1884. It houses the Hamilton Rooms, named after GER chairman Claud John Hamilton .

Extension of the station (1895)

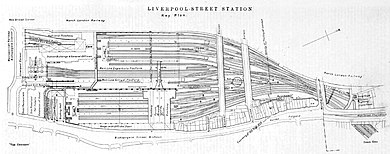

At the beginning, many thought the station was an expensive “ white elephant ”, but after only ten years its capacity was full (approx. 600 trains a day). After parliament had given its approval in 1888, work began in 1890 on an extension of eight tracks east of the existing station. Liverpool now owned most of the platforms of any London train station until the expansion of Victoria Station in 1908.

The station was widened by around 70 m to the east; additional shops and offices were built to the east of the new track hall up to the border of the parish of Bishopsgate-Street Without. The new part of the main hall also received its own roof. Chief engineer was John Wilson, architect was William Neville Ashbee . As part of the project, GER was obliged by parliament to relocate all tenants affected by the work. 137 were housed in existing buildings, the remaining 600 moved to new apartment buildings that the company had to build at its own expense. At the turn of the century, Liverpool Street had the most extensive suburban traffic in London and was considered one of the busiest train stations in the world. In 1912 around 200,000 passengers used it every day on around 1,000 different trains.

First World War and the interwar period

During the First World War the operation Türkenkreuz took place on 13 June 1917 in the 20 German bombers of the type Gotha GI flew an air attack on London. The attack hit several buildings, including Liverpool Street Station. Seven tons of explosives fell on the station, killing 162 people and injuring 432 others. It was the deadliest air raid on Britain during the war.

The Great Eastern Railway honored more than 1,000 of its employees who were killed in World War I, with a large war memorial of marble in the main hall. General Henry Hughes Wilson unveiled it on June 22, 1922; he was shot dead in front of his house a few hours later by members of the Irish Republican Army . A memorial plaque unveiled next to the GER monument a month later commemorates him. Since 1990 the war memorial has been located above the main hall, near the entrance from Liverpool Street. Another plaque commemorates the seaman Charles Fryatt , who tried to ram an enemy submarine with his ship in 1915 and was executed by the Germans a year later.

After the war, the station reached its capacity limits with over 230,000 passengers a day. GER considered electrifying the suburban lines to Chingford and Enfield, but could not afford it. Instead, GER introduced automatic signals at Liverpool Street Station and made changes to the track plan. The coaling and the water takeover took place directly in the station, which reduced turning times and increased productivity. As of July 2, a 10-minute cycle could be offered, with the adjustment costs only being £ 80,000 instead of the £ 3 million that would have been necessary if electrification had been carried out. This service , officially known as Intensive Service , which enabled a 50% increase in performance during rush hour, was popularly known as the Jazz Service . It was not maintained after the general strike in May 1926.

With the coming into force of the Railways Act 1921 on January 1, 1923, which provided for the reorganization of the fragmented British railway system, GER merged with several other companies to form the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER). The new owner neglected the station, which from the 1930s on made an increasingly dilapidated impression.

Second World War and electrification (1939–1960)

From November 1938 until the outbreak of World War II on September 1, 1939, thousands of Jewish children arrived at Liverpool Street Station as part of the Kindertransport rescue operation . To commemorate this event, Nicholas Winton unveiled the Memorial To The Child by artist Flor Kent in September 2003 . It consisted of a glass box that contained a bronze sculpture of a girl and original objects from the children who were rescued at the time. After only two years, the memorial had to be relocated to another location because the objects in the glass case began to deteriorate in bad weather. On the initiative of Prince Charles , the sculpture Kindertransport - The Arrival by Frank Meisler was set up instead in September 2006 .

In cooperation with the London Passenger Transport Board , founded in 1933, LNER began electrifying the Great Eastern Main Line between Liverpool Street and Shenfield with 1500 V DC . The work progressed slowly and had to be suspended for the entire duration of the war. Electric local trains ran to Stratford from 1946 and to Shenfield from 1949. At the same time, the electrification of two lines in north-east London and Essex led to a further relief of the Liverpool Street station, as the trains no longer ran to the above-ground terminus, but were bundled in the underground Central Line . In November 1960, the electrification of the suburban line to Chingford was completed.

Remodeling (1973–1991)

The British Railways Board , the London Transport Executive , the Greater London Council and the Ministry of the Environment presented a report on the modernization of rail transport in London in 1973. In particular, it recommended the renovation of Liverpool Street and Broad Street stations , which should be financed through real estate development on the site. Liverpool Street faced various problems, in large part due to the 1890 expansion. It was basically two train stations at one location, with two cross platforms connected by aisles, several ticket halls and an inefficient flow of traffic within the building. The rail infrastructure also restricted usability: trains with twelve wagons could only be handled on seven tracks and the arrangement of the exit tracks turned out to be a bottleneck. In 1975 British Rail announced plans to demolish both Liverpool Street and Broad Street and replace them with new buildings. The proposed demolition met with fierce public opposition and sparked a campaign led by John Betjeman . She forced a public hearing that lasted from November 1976 to February 1977.

As a result of the hearing, the roof of the western track hall from 1875 was to be preserved. It was repaired and strengthened as a result between 1982 and 1984. Repairs to the main roof followed, which were completed in 1987. The plans envisaged widening the station exit by two tracks; the neighboring Broad Street train station should also be included and relatively low office buildings constructed. In 1983/84 the project was reassessed. It was decided to keep the bottleneck, install a new signal system instead and limit the renovation to Liverpool Street. In this way, the area of the Broad Street station could be profitably released for office use. In 1985, British Rail signed an agreement with the construction company Rosehaugh Stanhope and the following year began the implementation of the Broadgate urban development with the demolition of Broad Street.

Work in the track area included building a short link to the North London Line . This enabled trains that had previously hit Broad Street to run to Liverpool Street. The station was rebuilt with a cross platform and received two new entrances, plus a new bus station on the southwest corner. By 1991, the Broadgate office district was built with 330,000 square meters of floor space on the site of the former Broad Street station and above the tracks of Liverpool Street station. The proceeds from the Broadgate project were used to finance the modernization of Liverpool Street. Queen Elizabeth II officially opened the converted station on December 5, 1991.

Further development (since 1991)

In 1991 an additional entrance was built on the east side of Bishopsgate, with an underpass under the street. Liverpool Street has been a "sister station" of Amsterdam Centraal since December 1993 , as evidenced by a plaque near the entrance to the underground station. On April 24, 1993 in Bishopsgate exploded a car bomb of the Provisional Irish Republican Army . Property damage to the amount of 250,000 pounds occurred at the station, especially in the area of the glass roof. Two days after the attack, the station could be put back into operation.

During drilling for the Crossrail project in August 2013, a 17th-century cemetery was uncovered just a few meters below the surface of Liverpool Street. The New Churchyard on the site of what was then Bethlem Royal Hospital contained the remains of several hundred people from all walks of life, including plague victims, convicts and unidentified corpses. Further excavations in 2015 revealed that over 3,000 people had been buried there.

In 2015, TfL Rail took over the suburban traffic between Liverpool Street and Shenfield from Abellio Greater Anglia , as a preliminary operation for Crossrail. Responsibility for the Lea Valley Lines from Liverpool Street to Enfield Town, Cheshunt and Chingford was transferred to London Overground in the same year .

Subway

business

Liverpool Street is the sixth busiest station on the London Underground . Under the station, subway tunnels cross on two levels. The platforms of the Circle Line , the Hammersmith & City Line and the Metropolitan Line , which belong to the sub-paving type, are located on the upper level . The lower level is reserved for the Central Line , which was built in the form of a tube track . The underground station is not barrier-free.

history

Liverpool Street station had been planned from the outset in such a way that a transition to the rapidly expanding London Underground network could be created. The Metropolitan Railway , the predecessor of today's Metropolitan Line, ran for the first time from Moorgate to Liverpool Street on February 1, 1875 , initially going into the station concourse to turn around. For this purpose, the trains used a tight connecting curve with a radius of only 70 meters and a steep gradient. On July 12, 1875, the Metropolitan Railway took its own underground station into operation, which was named Bishopsgate. In addition to the two side platforms 1 and 2, head platform 3 existed until 1994 for trains ending here from the west. On November 1, 1909, the subway station was renamed Liverpool Street.

On July 28, 1912, the Central London Railway (now the Central Line) reached Liverpool Street Underground Station from the bank . The low-lying platforms 4 and 5 formed the eastern terminus for over three decades. Moore vacuum tubes, which were over three times brighter than the incandescent bulbs common at the time, were used for lighting. During the German Air Force attacks on Great Britain in World War II (also known as The Blitz ), the underground station was one of the main places of refuge. After particularly violent attacks in the East End on November 7, 1940, many people flocked here and the staff opened the gates for the first time without asking for tickets. For the remainder of the war, the station proved to be the most practical shelter for the local population.

As part of the New Works Program , the Central Line was extended east to Stratford on December 4, 1946 . As a result, there were capacity bottlenecks in the station, which is why a new counter hall was built by 1951. During the July 7, 2005 terrorist attacks , assassin Shehzad Tanweer detonated a bomb on a Circle Line subway train that had just left the station for Aldgate . Seven people were killed.

Crossrail

From December 2019 Liverpool Street will be connected to the Crossrail line, a S-Bahn-like rail link through central London. Trains will run west via Paddington to Reading and Heathrow Airport and east to Abbey Wood and Shenfield . An additional barrier-free counter hall is currently under construction in the Broadgate office district southwest of the station. A pedestrian link linked to the platforms will lead to the ticket hall of Moorgate station , where there will be transfer options to the Northern Line and Northern City Line .

The TfL Rail- operated suburban trains between Shenfield and Liverpool Street will be routed west of Stratford into the new tunnel, while the timetable on the Great Eastern Main Line will be significantly increased. When Crossrail is fully operational, platform 18 in the main concourse of Liverpool Street Station will be closed to make way for the extension of platforms 16 and 17 to accommodate longer trains.

literature

- Alan A. Jackson: London's Terms . David & Charles, London 1984, ISBN 0-330-02747-6 .

- R. J. Campion: The Redevelopment of Liverpool Street Station . In: Urban Railways and the Civil Engineer: Conference Proceedings . Thomas Telford, London 1987, ISBN 978-0-7277-1337-7 .

- Denis Smith: London and the Thames Valley . In: Civil Engineering Heritage . Thomas Telford, London 2001, ISBN 0-7277-2876-8 .

- Michael C. Duffy: Electric Railways 1880-1990 . Institution of Engineering and Technology, London 2005, ISBN 0-85296-805-1 , pp. 73-75 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ COUNTS - 2016 - annual entries & exits. (Excel) (No longer available online.) Transport for London , 2017, formerly in the original ; accessed on April 1, 2018 (English). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Estimates of station usage, 2016/17 data. (Excel) Office of Rail and Road , 2017, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Waterloo quiet London's busiest station . In: Nick Pigott (Ed.): The Railway Magazine . tape 158 , no. 1334 . Mortons Media Group, Horncastle June 2012, p. 6 .

- ↑ Gothic style offices flanking the ramp, and the two western bays of the train shed, Liverpool Street station at. (No longer available online.) In: National heritage list of England. English Heritage , formerly in the original ; accessed on April 1, 2018 (English). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Signal Box: Liverpool Street London Underground. (No longer available online.) In: National heritage list of England. English Heritage, formerly in the original ; accessed on April 1, 2018 (English). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Jackson: London's Terms. P. 108.

- ^ A b New station for the Great Eastern. (PDF) (No longer available online.) The Engineer, October 27, 1865, p. 266 , archived from the original on March 4, 2016 ; accessed on April 21, 2018 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Liverpool Street Station, London. In: Network Rail Virtual Archive. Network Rail , July 2012, accessed July 28, 2014 .

- ^ A b John R. Kellett: The Impact of Railways on Victorian Cities . Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1969, ISBN 978-0-415-41813-3 , pp. 52 .

- ^ Ordnance Survey . 1: 5280, 1851; 1: 1056, 1875

- ^ A b c Architectural guide Liverpool Street. (PDF) (No longer available online.) Network Rail , archived from the original on February 21, 2014 ; accessed on July 29, 2014 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Jackson: London's Terms. P. 109.

- ^ Great Eastern Railway Company's new station at Liverpool Street. (PDF) (No longer available online.) The Engineer, June 11, 1875, p. 403 , archived from the original on September 24, 2015 ; accessed on April 21, 2018 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Campion: The Redevelopment of Liverpool Street Station. Pp. 97-98.

- ^ A b c d Smith: London and the Thames Valley. P. 177.

- ↑ Denis Smith: London and the Thames Valley , p. 176.

- ^ Kellett: The Impact of Railways on Victorian Cities , p. 64.

- ^ Campion: The Redevelopment of Liverpool Street Station. P. 98.

- ↑ Ben Weinreb, Christopher Hibbert, Julia Keay, John Keay: The London Encyclopedia . Pan MacMillan, London 2008, ISBN 978-1-4050-4924-5 , pp. 491 .

- ↑ The Enlargement of Liverpool Street Station, Great Eastern Railway. (PDF) (No longer available online.) The Engineer, June 8, 1894, pp. 494–495 , archived from the original on September 24, 2015 ; accessed on April 21, 2018 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Jackson: London's Terms. P. 114.

- ↑ a b c Jackson: London's Terms. P. 119.

- ↑ Justin D. Murphy: Military Aircraft, Origins to 1918: An Illustrated History of Their Impact . ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2005, ISBN 978-1-85109-488-2 .

- ^ Spotlights on history. The National Archives , accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Sir H. Wilson murdered. Shot on his doorstep. Two Irishmen captured. Running fight in London. The Times , June 23, 1922, p. 10.

- ^ Monument: Sir Henry Wilson at Liverpool Street Station. London Remembers, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ^ Monument: Fryatt at Liverpool Street Station. London Remembers, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Duffy: Electric Railways 1880-1990 . Pp. 73-75.

- ^ Michael Stratton, Barrie Tinder: Twentieth Century Industrial Archeology . E & FN Spon, London 2000, ISBN 0-419-24680-0 , pp. 163 .

- ↑ Jackson: London's Terms. P. 122.

- ↑ Jackson: London's Terms. P. 123.

- ^ Ruth Rothenberg: Kindertransport statue unveiled. The Jewish Cronicle, September 19, 2003, archived from the original September 21, 2016 ; accessed on April 1, 2018 (English).

- ^ Rachel Fletcher: Kindertransport monument derailed at Liverpool Street. The Jewish Cronicle, December 8, 2005, archived from the original on November 10, 2016 ; accessed on April 1, 2018 (English).

- ↑ Kitsch with a political message. The daily newspaper , July 18, 2008, accessed on April 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Duffy: Railways 1880-1990. P. 271.

- ^ WR Powell: Metropolitan Essex since 1919: Suburban growth. British History Online, 1966, pp. 63-74 , accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ^ Campion: The Redevelopment of Liverpool Street Station. P. 99.

- ^ Campion: The Redevelopment of Liverpool Street Station. Pp. 98-99.

- ^ Robert Thorne: Liverpool Street Station . Academy Editions, London 1978, ISBN 0-85670-402-4 , pp. 7 .

- ^ Campion: The Redevelopment of Liverpool Street Station. Pp. 105-106.

- ^ Campion: The Redevelopment of Liverpool Street Station. P. 102.

- ^ Campion: The Redevelopment of Liverpool Street Station. Pp. 106-107.

- ^ Campion: The Redevelopment of Liverpool Street Station. Pp. 107-109.

- ^ Anthony Sutcliffe: London: An Architectural History . Yale University Press, New Haven 2006, ISBN 978-0-300-11006-7 , pp. 204-205 .

- ^ Campion: The Redevelopment of Liverpool Street Station. P. 97.

- ↑ Main line masterpiece. The Times , December 6, 1991, p. 4.

- ^ Gordon Biddle: Railways in the Landscape . Casemate Publishers, Philadelphia 2016, ISBN 978-1-4738-6237-1 , pp. 180 .

- ↑ The Bishopsgate Bomb: One bomb: pounds 1bn devastation: Man dead after City blast - Two more explosions late last night. The Independent , April 25, 1993, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Liverpool Street reopens. The Times , April 26, 1993, p. 2.

- ↑ Crossrail dig unearths ancient burial site under Liverpool Street station. Evening Standard , August 8, 2013, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Plague pit with 3,000 skeletons uncovered at new Liverpool Street station ticket hall. The Daily Telegraph , March 9, 2015, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ^ Gwyn Topham: Clean, reliable and integrated: all change for neglected rail services in London. The Guardian , May 29, 2015, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ^ Rachel Holdsworth: TfL Confirms Takeover Of West Anglia Rail Services. Londonist, August 19, 2015, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ^ Hammersmith & City Line. Clive's Underground Line Guides, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Misc. abandonedstatons.org, 1997, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Central Line. Clive's Underground Line Guides, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ^ David Long: The Little Book of the London Underground . The History Press, Stroud 2010, ISBN 978-0-7524-6236-3 , pp. 50 .

- ↑ David Bownes, Oliver Green, Sam Mullins: Underground: How The Tube Shaped London . Allen Lane, London 2012, ISBN 978-1-84614-462-2 , pp. 155-156 .

- ^ London Attacks: Liverpool Street. BBC News , 2005, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Liverpool Street station. Crossrail, 2018, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Dean Nicholas: Crossrail, As It May Appear On The Tube Map. Londonist, November 19, 2010, accessed April 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Anglia Route Study. (PDF) Network Rail , March 2016, p. 34 , archived from the original on January 1, 2017 ; accessed on April 1, 2018 (English).

| Previous station | National Rail | Next train station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| final destination |

Abellio Greater Anglia Great Eastern Main Line |

Stratford | ||

|

Abellio Greater Anglia West Anglia Main Line |

Tottenham Hale | |||

|

Abellio Greater Anglia Tottenham Hale Line |

Hackney Downs | |||

|

Abellio Greater Anglia Stansted Express |

Tottenham Hale | |||

|

c2c individual trains to the LTS line |

Stratford | |||

| Previous station | London Overground | Next train station | ||

| final destination | to Enfield & Cheshunt | Bethnal Green | ||

| to Chingford | ||||

| Previous station | Crossrail | Next train station | ||

| final destination | "Shenfield Metro" (until 2018) |

Stratford | ||

| Farringdon | Elizabeth Line (from 2018) |

Whitechapel | ||

| Previous station | London Underground | Next station | ||

| Bank | Central Line | Bethnal Green | ||

| Moor gate | Circle Line | Aldgate | ||

| Metropolitan Line | ||||

| Hammersmith & City Line | Aldgate East | |||

Coordinates: 51 ° 31 '7 " N , 0 ° 4' 51" W.