Metropolitan Railway

The Metropolitan Railway , also known as the Met , was a predecessor of today's London Underground . It operated an extensive passenger and freight transport in the metropolitan area of the British capital London . Its first line opened on January 10, 1863 and ran from Paddington Station to Farringdon near the City of London . It was the first subway in the world.

The first line was extended at both ends, from which the Inner Circle was created by 1884 - a ring line around the city center operated together with the District Railway , which connected most of the terminal stations with one another. The Met reached Hammersmith in 1864 and Richmond in 1877 . From 1869, the north-western trunk line from Baker Street developed into the most important route . This led to the Middlesex countryside , where it stimulated the emergence of several new suburbs. It eventually reached to Verney Junction in Buckinghamshire , northeast of Oxford and more than 80 kilometers from central London. Ultimately, the Met was to become the heart of a railway network that would extend from Manchester and Liverpool via London and a tunnel under the English Channel to Paris ; however, these plans soon came to nothing.

In 1905, the Met introduced electrical operation and replaced the steam locomotives on most of its route network. However, steam trains operated individual sections outside London for decades. In contrast to other British railway companies, the Met had extensive properties. For this reason, property developments developed into an important business area. After the First World War, the Met marketed the newly emerging housing estates along its routes under the name Metro-land and praised them as a rural suburban idyll. On July 1, 1933, the Met went on together with the subways of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London and various tram and bus companies in the public company London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB).

Today, former routes and stations of the Metropolitan Railway are used by five lines of the London Underground ( Metropolitan Line , Circle Line , Hammersmith & City Line , Piccadilly Line and Jubilee Line ) as well as by the railway company Chiltern Railways .

history

From Paddington to the City of London (1853–1863)

Starting position

In the first half of the 19th century, the population of London increased two and a half times, and the urban area expanded significantly. The increasing unbundling of homes and workplaces meant that more and more people had to travel further. From the mid-1830s, railroad lines penetrated to the edge of the city center and within a quarter of a century eight terminal stations were built : London Bridge (1836), Waterloo (1848) and Victoria (1860) to the south, Shoreditch (1840) and Fenchurch Street ( to the east ) 1841), to the north Euston (1837) and King's Cross (1852), to the west Paddington (1838). Only Fenchurch Street was within the City of London , the capital's economic center. A large number of wagons , cabs and horse-drawn buses operated on the often narrow and winding road network , which severely impeded the flow of traffic. In addition, up to 200,000 people came daily to the City of London on foot.

The congested streets and the great distance to the train stations in the north and west led to several attempts to obtain the approval of parliament for the construction of new railway lines into the city. For example, in 1836 Robert Stephenson planned to extend the London and Birmingham Railway through a tunnel to the current location of the Savoy Hotel . In order to prevent apparently inevitable protests from local residents, a parliamentary commission came to the conclusion in 1846 that Parliament should not approve a project that provided for the construction of above-ground routes in the built-up central area.

This means that only underground railways remain as a possible solution to the traffic problems. A major sponsor of such projects was Charles Pearson . In 1845 he had proposed the construction of an atmospheric railway from the city to King's Cross station, which should run in an arcade just below street level. The Commission also rejected this proposal. In 1852 Pearson presented a new project, the construction of a central train station for several railway companies. This City Central Terminus was to be built near Farringdon on a site where a slum had recently existed and had been cleared. A link was also planned between Farringdon and King's Cross. Although the City of London supported the City Terminus Company (CTC) founded by Pearson, the rail companies were not interested. Joseph Paxton , who designed the Crystal Palace for the First World's Fair , proposed an above-ground atmospheric path called the Great Victorian Way in 1855 , which would be enclosed by a glass arcade along its entire length. The estimated cost of £ 34 million was astronomical and public funding was illusory given the laissez-faire attitude at the time . A similar project was the Crystal Way between St Paul's Cathedral and Oxford Circus, proposed by engineer William Moseley .

Establishment of the Metropolitan Railway

To connect the Great Western Railway 's Paddington station with King's Cross, the Bayswater, Paddington, and Holborn Bridge Railway Company was established. To this end, the company published a bill in the London Gazette in November 1852, and in January 1853 the boards of directors designated John Fowler as engineer at their first meeting . Charles Pearson was neither a director nor a major shareholder of the company, but he used his political influence to promote the project and secure its funding.

After successful lobbying , the company secured parliamentary approval in the summer of 1853 and renamed the North Metropolitan Railway (NMR). When Parliament rejected the CTC's proposal, it meant that NMR would not be able to reach the City of London via its King's Cross-Farringdon link. With Pearson's approval, the NMR took over the CTC and then submitted a new draft in November 1853. Compared to the original project, the line was to be extended south from Farringdon to the General Post Office and connected directly to the Great Western Railway (GWR) station in the west . The NMR also sought permission to build connections to the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) at Euston and the Great Northern Railway (GNR) at King's Cross - the latter using winches and elevators. With the submission of the bill, the company renamed itself Metropolitan Railway (Met for short). After detailed parliamentary deliberations, the Royal Assent was given on August 7, 1854, whereby the law known as the North Metropolitan Railway Act became legally binding.

The cost of construction was estimated at £ 1 million . The Met struggled to raise capital because of the Crimean War . In the meantime, she introduced two new bills in parliament to extend deadlines. A law to build a direct link to the GNR at King's Cross received royal approval in July 1855. Planning changes required the passing of the Metropolitan (Great Northern Branch and Amendment) Act 1860 and the Great Northern & Metropolitan Junction Railway Act 1864. Although the GWR promised to contribute £ 175,000 and the GNR promised to pay a similar amount, was At the end of 1857, not enough capital had been raised to begin construction. To reduce costs, the direct connection to the GWR station at the western end and the section south of Farringdon were eliminated. In 1858, Pearson negotiated an agreement between the Met and the City of London Corporation : the Met bought land on Farringdon Road for £ 179,000, while the corporation bought shares for £ 200,000. Parliament approved the route changes in August 1859, which meant that funding for the commitments made by the Met was finally secured. Other well-known shareholders were the building contractors Samuel Morton Peto and Thomas Brassey , who were hoping for lucrative contracts. The new company was headquartered at 17 Duke Street in Westminster , the former home of Isambard Kingdom Brunel .

Construction of the first line

There were concerns that buildings along the route could sink due to washouts and vibrations, and that thousands of people would receive financial compensation for the loss of their homes during construction. The radical Scottish preacher John Cumming explicitly warned of the consequences of the Metropolitan Railway: "The imminent end of the world would be accelerated by the construction of underground railways that dig into the hell regions and thereby disturb the devil." Nevertheless, construction began in May 1860. The The route between Paddington and King's Cross was mainly built using the cut- and- cover method , followed by a 666 meter long tunnel under Mount Pleasant, a small hill. The route then followed the River Fleet next to Farringdon Road in an open cut to near the new Smithfield meat market .

The cut was 33.5 feet (10.2 m) wide and had brick retaining walls that supported an elliptical brick arch or iron girders with a span of 28.5 feet (8.69 m). The tunnels in the stations were wider to leave space for the platforms . Workers known as navvies carried out most of the excavation work, but a simple conveyor system was also used to lift the earth out of the trench. The excavated material was dumped on a fallow site in Fulham , where the Stamford Bridge stadium was built around 15 years later (since 1905 the home of Chelsea FC ). The tunnel provided space for two tracks , six feet (1.83 m) apart. Three - rail tracks were laid for the use of standard-gauge GNR trains (1435 mm) and wide-gauge GWR trains (2140 mm).

Several accidents delayed the construction work. In May 1860, a GNR train did not stop in King's Cross station in time and fell into the construction pit of the Metropolitan Railway. There was enormous damage, but no fatalities. In the same year, a boiler bang from a construction train killed the driver and his assistant. A construction pit on Euston Road collapsed in May 1861, causing considerable damage to neighboring buildings. After a heavy rain shower in June 1862, the wall of the underground River Fleet burst and flooded large parts of the construction site. Workers on the Metropolitan Railway and the Metropolitan Board of Works managed to divert the water into the Thames . The incident caused construction delay of several months and an additional cost of £ 300,000. The first test drives on sections of the route took place in November 1861. The first trip over the entire route was carried out in May 1862; Among the invited guests was the then Treasury Secretary William Ewart Gladstone . The total construction cost was £ 1.3 million.

Opening and first years of operation

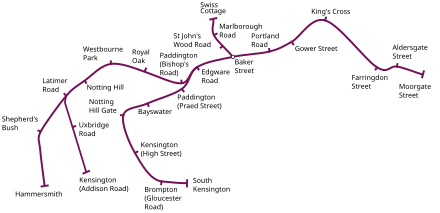

On December 22, 1862, the Board of Trade carried out the construction inspection of the line and recommended various changes to the railway signals. The last test drives took place on January 5, 1863. The official opening took place on January 9, 1863; it consisted of a short ceremonial sightseeing tour and a large banquet for around 700 shareholders and guests in Farringdon. Charles Pearson did not live to see the completion of the project; he had died almost four months earlier. The newspaper The Times , which had very critically appraise the project for a long time, has now turned out enthusiastically and wrote: "The Metropolitan Railway ... has become a great success. The line can be seen as a great technical triumph of our time. ”Scheduled operations began on January 10, a Saturday morning. The 6.0 km long route comprised seven stations: Paddington (Bishop's Road) (now Paddington ), Edgware Road , Baker Street , Portland Road (now Great Portland Street ), Gower Street (now Euston Square ), King's Cross (now King's Cross St. Pancras ) and Farringdon Street (now Farringdon ).

The railway turned out to be a great success. 38,000 passengers were counted on the opening day; additional GNR trains had to be used to relieve the burden. In the first twelve months, 9.5 million passengers used the train; this number rose to 12 million in the second year of operation. The first timetable stipulated a journey time of 18 minutes. Trains ran every 15 minutes during the day, every 10 minutes during rush hour, and every 20 minutes in the morning and evening. The Met was the first British railway company to offer workers' trains. Before 6 a.m., two trains ran in both directions at a discounted rate: With the single ticket, which was only valid on these trains in the morning, any train could be used for the return journey on the same day.

In the first few months, the Met used wide-gauge rolling stock from the GWR. Soon after the opening, there were disagreements between the two companies about the need for timetable consolidation. The GWR viewed the Metropolitan Railway merely as an extension of their Great Western Main Line into the City of London; She was skeptical of a purely inner-city operation and shared use by other companies. Finally, in July 1863, it announced that it would remove all of its rolling stock from the line within two months. After hectic negotiations, the Met's board of directors succeeded in renting standard-gauge rolling stock from GNR in August and continuing operations. The GWR sold its shares at a profit in October 1863, while the Met began to acquire its own steam locomotives and wagons in 1864 .

In the expectation that smokeless locomotives would be used, the line had been built with little ventilation and a long uninterrupted tunnel between Edgware Road and King's Cross. The condensation locomotives used turned out to be far less effective than assumed. Contemporary reports often described journeys in loud trains through dark, steam- and smoke-filled tunnels. The Met repeatedly denied that this was harmful to passengers. She even claimed that her employees were the healthiest railroad workers in the country and that the smoke had healing properties for asthmatic and bronchial ailments. Still, the Met improved ventilation by adding an extra opening between Gower Street and King's Cross and removing the glass roofs in the stations. As the problem persisted in the 1890s, a conflict arose between the Met and local authorities: the former wanted more openings to be built, the latter argued that this would frighten horses and reduce the value of surrounding land. A Board of Trade report published in 1897 recommended that additional openings be approved. However, due to electrification, it was no longer built.

Extensions and inner ring line (1863–1884)

Farringdon – Moorgate and the City Widened Lines

When the connections to the GWR and GNR were under construction and further connections to the Midland Railway (MR) and the London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LC&DR) were planned, the Met requested parliamentary permits in 1861 and 1864 for an additional pair of tracks between King's Cross and Farringdon and to build a four-track extension east to Moorgate . The Met claimed two tracks for itself, while the other two, as Widened Lines or City Widened Lines ("extended lines") designated tracks were mainly intended for use by other railway companies. Parliament approved these plans through the passing of the Metropolitan Railway Act 1861 and the Metropolitan Railway (Finsbury Circus Extension) Act 1861 , both of which came into force on July 25, 1864.

On October 1, 1863, two short single-track tunnels were opened at King's Cross to connect the GNR main line to the Met, whereupon suburban GNR trains ran to Farringdon. From the same day GWR trains ran from Farringdon to Windsor ; thus the GWR was present again at the Met after the temporary withdrawal in August 1863. Jointly operated trains of the LC&DR and the GNR used the Snow Hill Tunnel from January 1, 1866 , which began at the Blackfriars Railway Bridge and led north under the Smithfield Meat Market Hall to Farringdon. A few days earlier, on December 23, 1865, the extension to Moorgate was opened and from March 1, 1865 all four tracks of the extension were available. The second pair of tracks between King's Cross and Farringdon was first used by a GNR freight train on January 27, 1868. The branch to the Midland Main Line was in operation from July 13, 1868, three months before the opening of the St Pancras terminus of the MR. The last element of the Widened Lines was the commissioning of a connecting curve north of the Snow Hill Tunnel on September 1, 1871, creating a track triangle that allowed LC&DR to run trains to Moorgate.

Hammersmith & City Railway

In November 1860, the Met and GWR supported a bill to Parliament calling for the construction of a line known as the Hammersmith, Paddington and City Junction Railway . It was to branch off the Great Western Main Line a mile west of Paddington Station and open up the developing suburbs of Shepherd's Bush and Hammersmith , with a connection to the West London Railway (WLR) at Latimer Road. Parliament approved the project on July 22, 1861 as the Hammersmith and City Railway (H&CR) . The 3.9 km long and built on a 6.1 m high viaduct through a largely undeveloped area was opened on June 13, 1864. Broad-gauge GWR trains running from Farringdon opened up the stations of Notting Hill (now Ladbroke Grove ), Shepherd's Bush (replaced by what is now Shepherd's Bush Market in 1914 ) and Hammersmith . The connection to the WLR at Kensington station (Addison Road), today Kensington (Olympia) , followed just under three weeks later on July 1st. The operation was carried out by a car that was attached or detached in Notting Hill.

According to an agreement with the GWR, the Met operated standard gauge trains to Hammersmith and the GWR broad gauge trains to Kensington (Addison Road) from 1864. From 1867 the H&CR was jointly owned by both companies, after which the GWR also began to operate standard gauge trains. In 1869, the broad gauge tracks on the H&CR and the Metropolitan trunk line were removed. Parallel to the Great Western Main Line, two additional tracks for trains to Hammersmith went into operation between Westbourne Park and Paddington in 1871. In 1878 the branch at Westbourne Park at the same level was replaced by a flyover structure . In August 1872, the GWR extended its Addison Road connection via the District Railway to Earl's Court and Mansion House . This service, known as the middle circle , remained in place until January 1905, with trains only running to and from Earl's Court from July 1, 1900. Over the years, additional stations were added due to the denser development.

From October 1, 1877 to December 31, 1906, some trains on the H&CR continued to run on the London and South Western Railway (L & SWR) to Richmond . For this purpose they used the Hammersmith station (Grove Road) not far from the Hammersmith terminus.

Construction of the inner circle

The success of the Metropolitan Railway sparked a wave of motions to Parliament to build new rail lines in London in 1863, with many of the 259 projects submitted showing similar routes. In order to consider the best proposals, the House of Lords set up a special commission which published a report in July 1863. He recommended the construction of an inner circle , which should connect almost all terminal stations with each other. As a result, various projects were presented with a view to the parliamentary session in 1864, which more or less corresponded to the recommendation. A joint commission of members from both chambers of parliament set out to review the options. In November 1863, The Times reported that around 30 projects had been shortlisted, many of which were submitted "on the fly and without much consideration for construction costs or operational feasibility."

Proposals by the Met to extend the existing route from Paddington south to South Kensington and from Moorgate east to Tower Hill were approved by Parliament and received royal approval on July 19, 1864. In order to complete the ring line more quickly, the Commission supported the creation of a second company called the Metropolitan District Railway (commonly known as the District Railway ). To this end, on the same day she merged two projects that wanted to connect Kensington with the City of London on different routes. Initially, the District and the Met were closely linked and the intention was to merge the two companies soon. The Met's chairman and three other directors were on the District's board of directors, John Fowler was chief engineer of both companies, and work on all extensions was combined into a single construction contract. The District Railway was founded mainly to raise the required capital independently of the Met and thus to support the financial burden more broadly.

The western extension of the Met began just east of Paddington Station at the Praed Street junction and ran through the upscale neighborhoods of Bayswater , Notting Hill, and Kensington . The property values were higher here and, in contrast to the main route, the route did not follow the course of existing roads. Accordingly, the compensation payments were higher. At the address 23-24 Leinster Gardens a five-story false facade was built to hide the incision behind it. A 385 m long tunnel under Campden Hill was the only underground section. At the same time as the work on the Met, the District Railway was built. This also ran through affluent neighborhoods and the compensation payments were so high that the cost of the first section between South Kensington and Westminster was three million pounds - three times as much as the longer main line of the Met. The first section of the metropolitan extension to Brompton (Gloucester Road) (now Gloucester Road ) opened on October 1, 1868, with the Met operating a second station at Paddington Station. Almost three months later, on December 24, 1868, the Met continued eastward to the South Kensington community station . From there, the District opened its route to Westminster on the same day, which was extended to Blackfriars in 1870 .

Operations on the District Railway route were initially taken over by the Met's trains, which received 55 percent of gross income for a basic offer agreed in advance. The District had to pay for any additional trains it needed, so that its share of the revenue fell to around 40 percent over time. The accrued debt of the District meant that a merger was no longer attractive from the Met's point of view and was no longer pursued. In order to improve its financial situation, the District Railway decided not to renew the unfavorable company agreement. In view of the high construction costs, the District was not able to continue its route to Tower Hill as originally planned and was limited to a short extension from Blackfriars to Mansion House . After its opening on July 3, 1871, the District used its own rolling stock and both companies offered train connections between Moorgate and Mansion House on the as yet unfinished inner circle . The permits for the section east of Mansion House expired in the meantime.

In 1868 and 1869, the Met was the focus of criminal investigations when the judicial authorities accused the company of financial machinations. She'd paid out higher dividends than she could have afforded, and current expenses had been debited to the capital account. In 1870, the board of directors was found guilty of breach of trust and instructed to compensate the company. They all appealed and in 1874 they were able to obtain a much smaller amount. In order to regain the trust of the shareholders, they had all been replaced by October 1872. Edward Watkin , a member of the House of Commons and experienced manager who has served on the board of several other companies, has been appointed as the new chairman .

Due to the cost of the land acquisition, the extension of the Met east of Moorgate was slow, and in 1869 the Society had to ask parliament to extend its approval. Construction began in 1873, but when graves were found in the crypt of a Roman Catholic chapel, the contractor said he was struggling to keep the workers on site. The first section to the recently completed Liverpool Street terminus of the Great Eastern Railway (GER) opened on February 1, 1875. For a short time, when the Met station was still under construction, the trains ran over a 70 m long curve to the GER station. The Met station went into operation on July 12 of the same year and the connecting curve for regular trains was no longer necessary. As the route to Aldgate continued , workers came across hundreds of truckloads of ox horns six meters below the surface. A shuttle train initially ran from Bishopsgate station to the temporary terminus of Aldgate, which opened on November 18, 1876, and from December 4, all Met and District trains used this station.

Closing the gap and conflicts with the District Railway

The completion of the ring line was further delayed. Disappointed investors formed the Metropolitan Inner Circle Completion Railway Company in 1874 with the express purpose of completing the project. The society enjoyed the support of the District and received parliamentary approval on August 7, 1874. However, she did not succeed in raising the required capital and was granted an extension in 1876. In December 1877 negotiations between the Met and the District about closing the gap took place. The Met also expressed the wish to have access to the South Eastern Railway (SER) via the East London Railway (ELR) . In 1879, both companies received parliamentary approval for a connection to the ELR. The law known as the Metropolitan and District Railways (City Lines and Extensions) Act also ensured future cooperation by granting both companies access to the entire ring line.

On September 25, 1882, the Met extended its route from Aldgate to a temporary station at the Tower of London . In 1883 she commissioned the construction of two routes from Mansion House to Tower of London and from a junction north of Aldgate to Whitechapel . From October 1, 1884, Met and District trains ran on the " St Mary’s Curve" branching off just before Whitechapel to the ELR route, via which the SER's New Cross station could be reached. After an official opening ceremony on September 17 and a test run, the entire length of the ring line was opened to regular traffic on October 6, 1884. On the same day, the Met extended the trains coming from the H&CR via the ELR to New Cross. Initially, eight trains per hour ran on the ring line, which took 81 to 84 minutes to travel the 21 km long route. It proved impossible to keep this timetable, so in 1885 it was adapted to six trains every hour with a journey time of 70 minutes. The conductors were initially forbidden to take breaks during their shift, until in September 1885 they were guaranteed three breaks of 20 minutes each.

The fact that closing the gap in the ring line was delayed for so long was also due to the increasingly poor relationship between the Met and the District. The main reason for this was the appointment of James Staats Forbes as chairman of the district board in 1872 . Forbes also held the same role at LC&DR, which fought fierce competition with the Edward Watkin-led SER in south-east England. The hostility of both men led to the fact that in 1877 the agreement to close the gap in the ring line only came about after mediation by a neutral building contractor. Parts of the ring line were jointly owned by both companies, so that joint operation was essential. But just six days after the ring line was fully operational, an open conflict broke out: The Met closed the station at the Tower of London on October 12, 1884 after the District refused to sell tickets there. Due to poor coordination, Met and District trains often blocked each other and caused long delays. Both companies operated their own ticket offices and tried to steal passengers away from the competition with aggressive advertising campaigns.

Expansion to the northwest (1868–1899)

From Baker Street to Harrow

On April 13, 1868, the Metropolitan & St John's Wood Railway (M & SJWR) opened a single-track tunnel from Baker Street to Swiss Cottage . The intermediate stations at St John's Wood Road and Marlborough Road had switches and the Met ran the route with a shuttle train every 20 minutes. It built a connection to the ring line, but after 1869 there were no more continuous trains.

In the early 1870s, passenger numbers were low and the M & SJWR sought to extend the route to generate more traffic. Edward Watkin made this a priority as the construction costs would be lower than in the built-up area and the fares would be higher. In addition, the route would serve as a feeder to the ring line. In 1873 the M & SJWR received permission to build as far as Neasden in the middle of the Middlesex countryside . However, since the closest place was Harrow, it was decided to run the route up there; In 1874 the parliament granted the corresponding approval. In order to open up the grounds of the agricultural exhibition of the Royal Agricultural Society of England in Kilburn, a single-track line was first built to West Hampstead , which went into operation on June 30, 1879 (with a temporary platform on Finchley Road ). On August 2, 1880, the line was extended to Harrow . Two years later, the Met absorbed the M & SJWR and expanded the tunnel between Baker Street and Swiss Cottage to double lane.

In 1882 the Met relocated its depot from Edgware Road to Neasden. A locomotive works was added there in 1883, and a gas works in 1884. To accommodate over 100 workers who would move here from London, the Met built a railroad settlement with 100 rentable homes and ten shops. Two of these shops were used as classrooms and prayer rooms from 1883, and two years later the Methodists were given land to build a church and a school for 200 children.

From Harrow to Buckinghamshire

In 1868 the Duke of Buckingham had opened the Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway (A&BR), a 20.5 km single-track line from Aylesbury to Verney Junction station on the existing Oxford – Bletchley line . Relations with the LNWR, which operated the Oxford – Bletchley route, were poor, which is why the A&BR sought cooperation with the Metropolitan Railway. She had permission to build a line between Aylesbury and Rickmansworth . The Duke of Buckingham and Watkin agreed to extend the route to Harrow, where they would meet the Met. Parliament gave the appropriate approval in 1874 and Watkin was a member of the A&BR Board of Directors from 1875. The money to finance the project could not be raised and the permit expired, which is why the Met had to ask Parliament for new permits for a railway line between Harrow and Aylesbury in 1880 and 1881.

After some delay (caused by financing problems), the Harrow- Pinner section was opened on May 25, 1885 . From September 1, 1887, trains ran hourly from Baker Street to Northwood and Rickmansworth. The next stage was the commissioning of the section from Rickmansworth via Chalfont & Latimer to Chesham on July 8, 1889. On July 1, 1891, the Met took over the A&BR. The last missing section from Chalfont & Latimer via Amersham and Stoke Mandeville to Aylesbury went into operation on September 1, 1892, initially with a temporary station of the Met in Aylesbury. In 1894 the Met and the GWR opened a community station in Aylesbury. On the section between Aylesbury and Verney Junction, the bridges were too weak for the Met's locomotives. As the GWR refused to provide suitable rolling stock, locomotives had to be temporarily borrowed from the LNWR. The Met expanded the route taken over from the A&BR to double-track and mainline standard, as well as renewing the stations. This made it possible for the company to offer continuous trains from Baker Street to Verney Junction from January 1, 1897.

From Quainton Road station north of Aylesbury, the Duke of Buckingham had the Brill Tramway built at his own expense in 1871 , a 10.5 km long light rail . It was initially operated as a horse-drawn tram and switched to steam operation a year later. An extension to Oxford was planned several times, but never came about. The Met took over operations on the Brill Tramway on December 1, 1899 and rented the route for £ 600 annually. In 1903 she had the tracks re-laid and the stations rebuilt.

Broken visions

With the expansion into the rural areas of the counties of Middlesex , Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire , Edward Watkin pursued the long-term vision of a main line , the heart of which would be the Metropolitan Railway. In addition to serving as Chairman of the Board of the Met and SER, he was also Chairman of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR). He was also a member of the board of directors of the French railway company Compagnie des chemins de fer du Nord . Watkin sought a coherent railway network under his control, which should extend from Manchester and Liverpool via London and Calais to Paris . In 1872 he was a co-founder of the Submarine Railway Company , which began to carry out test bores with tunnel boring machines on both sides of the English Channel (in Dover and Sangatte ) in 1881 . Despite a public relations campaign aimed at attracting influential figures such as William Ewart Gladstone and the Archbishop of Canterbury to his side, the project had to be abandoned due to great political pressure when the Board of Trade ordered an immediate construction freeze in May 1882. In particular, General Garnet Wolseley saw the tunnel as a possible invasion route for French troops and therefore viewed it as a threat to national security.

Even if the Channel Tunnel had been built, it seems questionable that the Met would have been able to fulfill its intended role as a central link. The Met had long since developed into a predominantly inner-city mode of transport: in 1897, the section between Paddington and Farringdon was used by 528 passenger and 14 freight trains every day. With one train every three minutes on average, this route had reached its capacity limit.

In 1893 the Met opened Wembley Park Station . It initially served to develop the field of the Old Westminster Football Club , but after a short time numerous sports and leisure facilities as well as an exhibition center were built there. These were located on the site of a former country estate that the railway company had acquired in 1881. In order to generate even more excursion traffic, Watkin commissioned the construction of Watkin's Tower, named after him, in 1891 . The observation tower was to be 350 m high and clearly tower above the recently opened Eiffel Tower in Paris . The construction work dragged on and in 1895 the tower was only around 47 m high. It turned out that the tower would collapse due to the settlement if it was continued. The tower stump known as Watkin's Folly ("Watkins Madness") was finally demolished in 1907.

Relations with the Great Central Railway

After the failure of the Channel Tunnel project, Watkins still had the option of creating a new main line between London and the MS&LR network. The construction of a 159 km route was intended to link their route network in the Midlands with the Met immediately north of Aylesbury. There were considerations to use Baker Street as London's terminus, but around 1891/92 the MS&LR came to the conclusion, due to the lack of space, that a separate station with freight facilities, about half a kilometer west of it around Marylebone , would be more suitable. In 1893 the parliament passed a corresponding law. Watkin became seriously ill and had to give up all his offices in 1894. For a while after his resignation, relations between the two companies were strained.

In 1895 the MS&LR introduced a bill in parliament. He planned to build two additional tracks from Wembley to Canfield Place (near Finchley Road station ), on which their express trains would overtake the slow trains of the Met. After disagreement, both parties agreed that the tracks should be built by the Met, for the sole use of the MS&LR. When the Met rebuilt the bridges in the section between Wembley Park and Harrow on their behalf, they realized that a four-track section would be essential for future development, and laid additional tracks. The MS&LR requested exclusive use of two tracks. The company had the necessary authorization to join its Marylebone route to the ring line, but the Met made conditions difficult to meet. Since the MS&LR threatened to run out of money, they renounced this connection.

Because of the strained relationship, the MS&LR was dissatisfied with being entirely dependent on the Met for the London connection. Unlike their own route network in the north, south of Aylesbury there were several speed limits and long inclines. In 1898 the MS&LR and the GWR brought together a bill in parliament for the construction of the jointly operated Great Western and Great Central Joint Railway (GW & GCJR). Short connections from Grendon Underwood (north of Quainton Road) to Ashendon and from Northolt to Neasden were also planned. The Met filed a complaint claiming the bill was incompatible with the spirit and terms of the agreements it had made with MS&LR. The MS&LR was allowed to continue with their project, but the Met was awarded the right to compensation. A temporary agreement allowed the MS&LR to run four coal trains a day on the Met routes from July 26, 1898. The MS&LR wanted these trains to run on the GWR route between Aylesbury and Princes Risborough into London, but the Met countered that this was not part of the agreement. In the early morning hours of July 30, 1898, the Met in Quainton Road refused a train that was supposed to run on the GWR route, so that it had to turn north. In a subsequent court hearing, the Met was found to be right, as it was a temporary agreement.

In 1897 the MS&LR changed its name to Great Central Railway (GCR) to reflect its ambitions. On March 15, 1899, the Great Central Main Line between London Marylebone and Manchester Central was opened for passenger traffic. Negotiations between the GCR and the Met over the use of the section south of Quainton Road dragged on for several years until the two companies agreed in 1906 that the GCR would lease two tracks between Canfield Place and Harrow for 20,000 pounds annually . GCR and Met formed the joint venture Metropolitan and Great Central Joint Railway (M & GCJR), which leased the Harrow to Verney Junction line and the Brill branch line for £ 44,000 annually. In return, the GCR undertook to provide transport services on the route worth at least 45,000 pounds. Aylesbury station, which had been operated jointly by the GWR and the Met, was placed under the management of a committee of the GW & GCJR and the M & GCJR. The M & GCJC took over the management of the other stations and the route, but did not have its own rolling stock. For the first five years, the Met provided management, while the GCR was responsible for accounting, after which both companies changed roles every five years until 1926. The line was maintained by the Met south of milestone 28.5 (south of Great Missenden) and the GCR north of it. The Great Central Line was the 1969 Beeching cuts victim

Electrification (1900-1914)

development

At the beginning of the 20th century, the traditional steam-powered underground railways were increasingly competing with new electric tube railways in central London. The commissioning of the Central London Railway from Shepherd's Bush to the City of London with a flat tariff of two pence meant that the District and the Met together lost four million passengers between the second half of 1899 and the second half of 1900. The smoke-laden air in the tunnels was increasingly unpopular with passengers and electrification was the solution. The Met had already considered electrification in the 1880s, but this new type of traction was still in its infancy. An agreement with the district was also necessary because of the joint ownership of the ring line. A jointly procured test train with six carriages ran from May to November 1900 on the District section between High Street Kensington and Earl's Court . The test operation with passengers proved to be a success and in 1901 a tender followed . Based on the recommendation of a jointly set up committee, the Met and the District agreed on a three-phase AC system with overhead lines , an offer from the Hungarian manufacturer Ganz .

In 1902 the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) took control of the District. This holding was headed by the American financier Charles Tyson Yerkes , who, based on his experience in the USA , preferred a direct current system with a conductor rail , similar to the City and South London Railway and the Central London Railway. After arbitration by the Board of Trade , an agreement was reached on direct current with two busbars. Both companies wanted to use both railcars and electric locomotives . In December 1904, the Met in Neasden put a coal-fired power station with an installed capacity of 10.5 MW into operation. This generated an electrical voltage of 11 kV at 33.3 Hz, which was converted to 600 V in five substations .

In the meantime, the District had begun building a line from Ealing to South Harrow , and had permission to extend it to Uxbridge . In 1899, the District was in financial difficulties, whereupon the Met offered a rescue package: They would build a branch line from Harrow to Rayners Lane and take over the line to Uxbridge. The District would be granted the right to allow up to three trains to run on it every hour. In the same year the parliament passed a corresponding law and in September 1902 the construction of the 12.1 km long branch line began. This required 28 bridges and a 2.4 km long viaduct with 71 arches at Harrow. During construction, the Met decided to electrify the Uxbridge branch line, along with the Baker Street to Harrow line, the ring line, and joint GWR and H&CR lines. The Met opened the line to Uxbridge on June 30, 1904, initially using steam-powered trains. Because of the still low building density, intermediate stations were only added in the following years.

Electrical operation

Electric railcars operated from January 1, 1905, until March 20, all local trains between Baker Street and Harrow were electrically powered. On July 1, 1905, the Met and District multiple units started operating on the ring line, but on the same day a Met multiple unit overturned the positive pole line on the District section. It turned out that the pantograph attached to the Met trains was incompatible with the District power rails. The Met trains were then withdrawn and adjusted. When electrical operation could be fully started on September 24, 1905, the travel time for the entire ring line was reduced from 70 to 50 minutes.

The GWR built a 6 MW power station at Park Royal and electrified the line between Paddington and Hammersmith and the branch line from Latimer Road to Kensington (Addison Road). On November 5, 1906, she began electrical operations on the H&CR with rolling stock that she owned together with the Met. That same year, the Met ceased operations on the East London Railway and their trains temporarily turned at Whitechapel Station in the District. From December 31, 1906, electric trains on the H&CR only ran to Hammersmith, the short connection to the L & SWR tracks in the direction of Richmond was then used by GWR steam railcars for a further four years .

The line northwest of Harrow towards Verney Junction had not been electrified. Trains from Baker Street were initially pulled by an electric locomotive and replaced by a steam locomotive on the way. From January 1, 1907, this change took place in Wembley Park station, from July 19, 1908 in Harrow. During the rush hour, the GWR continued to operate through trains to the City of London, with the steam locomotives in Paddington being disconnected and electric railcars being harnessed from January 1907. Through freight trains to the Smithfield meat market hall as well as individual excursion trains continued to use steam locomotives on the ring line. In 1908 the Met appointed Robert Selbie as managing director, a position he held until 1930. In 1912 the Baker Street station was rebuilt and now had four tracks with two central platforms. To cope with the increasing volume of traffic, the Met built further four-track sections: in 1913 from Finchley Road to Kilburn and in 1915 from Kilburn to Wembley Park. The section between Baker Street and Finchley Road remained two-lane, so that there was a bottleneck.

Reluctant cooperation with London Underground

In order to advertise travel on the London subway, the companies entered into a joint marketing agreement. In 1908, the Met joined this program, which included route network maps, joint advertising and continuous tickets. In the city center, the stations were given signage with the brand name U NDERGROUN D. Finally, the UERL controlled all underground trains with the exception of the Met and the Waterloo & City Line . She introduced station signs with red discs and blue bars (this logo is still used today in a modified form). The Met responded with its own station signs, composed of a red diamond and a blue bar. Further cooperation in the form of a management conference stalled when Robert Selbie withdrew in 1911. The Central London Railway had set the prices for annual subscriptions significantly lower than those on the competing routes of the Met without any consultation with the conference. Selbie rejected a proposed merger with the UERL; In November 1912, a press release made it clear that the Met's interests were primarily outside of London, in cooperation with long-distance railway companies and in freight transport.

East London Railway

After the Met and District withdrew from the East London Railway in 1906, the South Eastern Railway (SER), the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB & SCR) and the Great Eastern Railway carried out rail operations. Both the Met and the District wanted the line to be electrified, but did not want to bear all of the costs themselves. Negotiations took place between the companies involved and an agreement was reached in 1911. The line was to be electrified, with the UERL supplying the electricity and the Met carrying out the train operations. The corresponding approval of the parliament was available in 1912 and from March 31, after a six-and-a-half year interruption, there was again an underground service on the line. From New Cross and New Cross Gate , the train stations of SER and LB & SCR, the Met operated two trains per hour to South Kensington and eight shuttle trains to Shoreditch . The route, now known as the East London Line, remained an underground line until 2007, after which it was integrated into the London Overground S-Bahn network .

Great Northern & City Railway

In 1891 the civil engineer James Henry Greathead presented plans for a railway line between Finsbury Park and Moorgate . On this, trains of the Great Northern Railway (GNR) should run directly into the City of London without having to make a detour via King's Cross. The GNR was initially open to the plans, but the start of construction was delayed until 1898 and the railway company terminated the cooperation with the responsible Great Northern & City Railway (GN&CR). Despite this setback, the GN&CR built the line anyway, the tunnel being aligned with the usual clearance gauge of the British railways and thus much wider than the London tube railways. The largely underground line was opened on February 14, 1904, without a track connection to the GNR in Finsbury Park.

Concerned that the GNR could change its stance and use the GN&CR instead of the Widened Lines as before , the Met sought to acquire the direct connection. In 1912 she introduced a bill that would also allow her to connect the GN&CR with the Ring Line and the Waterloo & City Line. Parliament approved the takeover in 1913, but deleted the additional projects from the law after property owners in the city had appealed against them. In 1914, the Met and the GNR presented a joint bill that would have allowed a rail link to be built in Finsbury Park (which would have been the original plans of 1891). This time the North London Railway appealed and the initiators withdrew the draft.

First World War and "Metro-land" (1914–1932)

A few days after the outbreak of World War I , the Met was placed under the operational supervision of the Railway Executive Committee , a government agency. The Met had to cope with a significant drop in staff, as many employees had volunteered for the war. In 1915, the Met began using women as ticket sellers and conductors. During the war, the widened lines were of great strategic importance as a connection for troop transports and freight trains between the railway lines in the north and the ports on the English Channel . In the four years of the war, 26,047 military trains used the widened lines, which transported over 254,000 tons of material. Because of the tight curves, hospital trains with returning wounded could not use the route. The official supervision ended on August 15, 1921.

Development of "Metro-land"

Laws passed by parliament on the construction of railway lines allowed the companies to expropriate the planned route . Sometimes they bought larger pieces of land from the landowners than they actually needed to avoid the legal obstacles involved. After completing the route, the railway companies were obliged to sell back land that was not operationally necessary to the original owner within a certain period of time at the same price; these then benefited from an increase in value due to the better accessibility. The Met, on the other hand, found itself in a privileged position: it was the only British railway company to have achieved through clever lobbying in Parliament that it was not subject to any sales force. The land she was allowed to keep was initially administered by the Land Committee , which was made up of directors from the Met. In the 1880s, when the Met expanded beyond Swiss Cottage and built the railroad settlement in Neasden, they built roads and sewers in the Willesden Park Estate and sold the parceled land to contractors for a profit. A similar project followed in Cecil Park near Pinner, and after the failure of Watkins Tower, lots were also sold in Wembley Park .

In 1912 Robert Selbie came to the conclusion that more professionalism was required when selling land and proposed the establishment of a separate company to develop new settlements along the railway lines instead of the Land Committee . The First World War delayed these plans for years. The Met was concerned that Parliament might reconsider its exclusive legal situation and sought legal advice. An expert opinion revealed that the right of ownership to the land was undisputed, but that the Met was not authorized to develop it itself. When a building boom began to emerge in 1919, the Metropolitan Railway Country Estates Limited (MRCE) was founded, with all the directors of the Met including one exception. The MRCE developed the housing developments Kingsbury Garden Village near Neasden, Wembley Park, Cecil Park and Grange Estate near Pinner, Cedars Estate near Rickmansworth and Harrow Garden Village.

The term Metro-land was created by the marketing department of the Met in 1915 when they gave the previously published Guide to the Extension Line the new name Metro-land . This travel guide with a high proportion of advertisements cost two pence and presented the region served by the Met. It was aimed at visitors, hikers and cyclists, but especially at potential home buyers. The travel guide, which was published annually until 1932, extolled the advantages of "good air in the Chilterns ", sometimes using extremely flowery language. A comfortable life in a modern house in the middle of a beautiful landscape, with a fast train connection to central London was advertised. The suburban settlements that arose along the Met largely corresponded to the ideal of the garden city propagated by Ebenezer Howard and mainly attracted middle-class families . Within a few decades, the population in the region served by the Met multiplied.

The Met was also involved in the real estate business in the city center. The best-known example is Chiltern Court , which opened in 1929 , is a large apartment building that was built over Baker Street Station. It included numerous shops and luxury apartments with three to ten rooms. Prominent residents such as the writers Arnold Bennett and HG Wells or the artist Edward McKnight Kauffer created an additional advertising effect. The architect was Charles Walter Clark , who was also responsible for the planning of several new station buildings in the outer part of "Metro-land" during this period.

Further infrastructure improvements

The introduction of more powerful electric locomotives in 1923 made it necessary to increase the installed capacity in the Neasden power station to 35 MW. From January 5, 1925, electric trains ran beyond Harrow to Rickmansworth . This made it possible to switch to steam operation there. The British Empire Exhibition took place in 1924 and 1925 . To cope with the expected crowds, the Met rebuilt Wembley Park station ; it received a new central platform, from where a covered pedestrian bridge led to the exhibition area. A national sports arena, the Wembley Stadium with a capacity of 125,000 spectators, was built at the former location of Watkins Tower . The stadium opened on April 28, 1923 with the FA Cup Final between the Bolton Wanderers and West Ham United . Before the game began, there were chaotic scenes when far more people streamed into the stadium than capacity allowed. In the 1926 edition of Metro-land, the Met boasted that it carried over 152,000 passengers to Wembley Park that day.

Although Watford had had a station on the West Coast Main Line since 1837 , the local trade association had approached the Met in 1895 with a proposal for a route via Stanmore to Watford. Together with the district administration, she approached the Met again in 1904 to discuss a shorter branch route from Rickmansworth and Moor Park . In 1906 a possible route was measured and six years later the Met and the GCR jointly introduced a bill for a branch route to the city center. A planned dam through the middle of Cassiobury Park encountered local resistance, so the route to a terminus immediately south of the park was shortened. The revised law came into force on August 7, 1912, but the outbreak of war in 1914 delayed the start of construction by years. After the end of the war, the Trade Facilitation Act passed in 1921 guaranteed government financial guarantees for major projects. Benefiting from this, construction work could begin in 1922. The Met opened the branch on November 2, 1925. Multiple units ran via Moor Park and Baker Street to Liverpool Street, steam trains of the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER), which had replaced the GCR in 1923, to Marylebone. The Met also operated a shuttle train on a connecting curve to Rickmansworth.

In 1924/1925, the Met replaced the same-level junction north of Harrow with a 370 m long flyover structure to separate the trains on the main line and the Uxbridge branch line. In 1927 the Met made another attempt to extend the Watford branch line through Cassiobury Park into the city center. She acquired a property on central Watford High Street with the intention of converting it into a station building. Plans for a tunnel under the park proved controversial and the Met abandoned the plans. More than 90 years later, the Croxley Rail Link is supposed to be a connection between Rickmansworth and Watford, albeit on a different route.

A bottleneck remained at Finchley Road , where the express and local railroad tracks met. In 1925, the Met presented a project for two new tunnels that branch off northwest of Kilburn & Brondesbury and lead to Baker Street via Edgware Road . The project was not pursued after the Ministry of Transport revised its regulation on “Requirements for Passenger Lines”. These required emergency exits at the ends of the train in deep-lying tunnel tubes, but the rolling stock used north of Harrow did not meet these requirements. Edgware Road station had been rebuilt with four platforms and had train destination indicators showing destinations such as Uxbridge and Verney Junction.

In 1929 construction began on a branch line from Wembley Park to Stanmore to open up the new Canons Park residential area. The government again guaranteed the funding. The project also included upgrading to four lanes between Wembley Park and Harrow. The branch line was opened on December 9, 1932 and was thus the last major project of the Met as an independent company.

Transition to the London Passenger Transport Board (1933)

The development of metro-land properties near their routes made up a significant portion of the revenue. The Met was always able to distribute a dividend to its shareholders, even if the amount was often subject to fluctuations. The financial statements of the early years should be treated with caution, but towards the end of the 19th century the dividend was 5%. It continued to decline from 1900 as electric trams and the Central London Railway stole the Met's passengers. In 1907/08 it reached a low of 0.5%. When passengers increased their use of the Met again after electrification, it rose to 2% in the years 1911 to 1913. The outbreak of the First World War halved it to 1%, and in 1921 the better business performance allowed a dividend of 2.25%. . Due to the post-war building boom, it rose to 5% by 1924/25. The general strike of 1926, which particularly affected the transport sector, caused the dividend to be reduced to 3%; this rose again to 4% by 1929.

In 1913, the Met had rejected a merger proposed by the UERL and stubbornly remained on its independent course under the leadership of Robert Selbie. The Railways Act 1921 , which came into force in 1923, led to the merger of over 120 railway companies into four companies. In the drafting phase, the Met was also included in the list of companies to be merged, but Parliament ultimately decided not to merge the London Undergrounds.

When proposals for standardizing public transport in London came on the agenda in 1930, the Met argued that it should have the same status as the four major rail companies. It is also incompatible with the UERL subways because of the freight traffic. The government, however, put the Met on the same level as the District, as they jointly operated the ring line. A draft law was published on March 13th, which initially aimed mainly at coordinating the small, independent bus companies. The Met feared this was just the first step towards the forced merger and invested £ 11,000 to lobby against it. The draft law survived a change of government in 1931. When the new government suggested that the Met remain independent if it gave up its operating rights on the ring line, the company declined to respond. The board of directors set about negotiating compensation for the shareholders, especially as the number of passengers declined due to the effects of the global economic crisis . In 1932, the last full year of its independence, the Met paid a dividend of 1 5⁄8%. On July 1, 1933, the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) was founded as a public company, in which the Met, the other subways as well as tram and bus companies were absorbed. Met shareholders received LPTB shares valued at £ 19.7 million in compensation.

Aftermath

In the unified London public transport system of the LPTB, which appeared under the brand name London Transport , the Metropolitan Railway became the Metropolitan Line . The LPTB closed the Brill branch on November 30, 1935, and the section between Quainton Road and Verney Junction on July 4, 1936. While the LPTB concentrated on electrical operation, LNER carried out the remaining steam operation and freight traffic on its behalf. In 1936 the Metropolitan Line was extended from Whitechapel to Barking , parallel to the District Line . The New Works Program , adopted in 1935, triggered extensive construction work. One element of this investment program was the construction of new tunnels and stations on the Bakerloo Line between Baker Street and Finchley Road. They began operating on November 20, 1939, making it possible to transfer local traffic to Wembley Park and on the Stanmore branch line to the Bakerloo Line. The branch line, in turn, was transferred to the new Jubilee Line in 1979 . In the London Underground network, the Great Northern and City Railway (now known as the Northern City Line ) remained isolated and operated as a section of the Northern Line until British Rail took it over in 1976 and integrated it into the national rail network.

Steam locomotives were used northwest of Rickmansworth until the early 1960s. On September 12, 1960, the section between Rickmansworth and Amersham was electrified, along with the branch line to Chesham . The last underground train pulled by a steam locomotive ran on September 9, 1961. The following day, British Rail took over operations on the last non-electrified section between Amersham and Aylesbury, using diesel multiple units. Since the privatization of British Rail in 1996, is on the railway line London-Aylesbury the railway company Chiltern Railways responsible. The Hammersmith – Barking route has been operated under the name Hammersmith & City Line since 1990 . The Metropolitan Line has since been limited to the Aldgate – Baker Street section and the adjacent north-western branches.

After the merger in 1933, the brand name "Metro-land" was quickly dropped. Writers like George Robert Sims or Evelyn Waugh as well as various interpreters of the Music Hall scene immortalized Metro-land in their works as early as the 1920s, so that the term stuck in the collective memory. John Betjeman brought the spirit of Metro-land to mind through poems like Middlesex and Baker Street Station Buffet , which appeared in the anthology A Few Late Chrysanthemums in 1954 . Betjeman achieved great public awareness through the documentary Metro-land , which the BBC first broadcast on February 26, 1973. In television series such as Mit Schirm, Charme und Melone , Simon Templar , Der Baron or Randall & Hopkirk , the stereotype of an apparent suburban idyll with dark secrets solidified. In 1980 Julian Barnes published the educational novel Metroland , in which the region plays an important role. Based on the novel, Philip Saville made the film of the same name in 1997, with Christian Bale and Emily Watson in the leading roles.

Freight transport

Freight traffic on the Met's network began on February 20, 1866, when the Great Northern Railway (GNR) ran regular freight trains via Farringdon to the London, Chatham & Dover Railway (LC&DR) network. From July 1868, the Midland Railway (MR) followed suit . In addition to the GNR and the MR, the Great Western Railway also built a freight shed in the Farringdon area; the connection was made via the widened lines . In contrast, the Met was initially limited to passenger traffic. This changed fundamentally with the construction of the trunk line northwest of Baker Street. In 1880 the Met secured the coal shipments of the Harrow District Gas Company . For this purpose, they used a siding that led from Finchley Road to a coal yard in Harrow. On the newly added sections of the main line, the Met equipped most of the stations with goods sheds and coal storage areas from the start. Goods destined for London were initially transshipped in Willesden, from where they were taken to their destinations by carts or trains of the MR. Later connections to the network of the Great Central Railway were added, in the north at Quainton Road, in the south at Neasden.

In 1909 the Met opened a goods shed on Vine Street near Farringdon Station; the two sidings were each seven cars long and enabled regular freight traffic to West Hampstead. The freight trains with a maximum of 14 cars were pulled by electric locomotives. The weight was limited to 254 tons in the city center and 229 tons on the way back. In 1910, 11,600 tons of goods were handled on Vine Street; this number increased to 25,500 tons by 1915. In 1913, the maximum capacity had already been exceeded, but after the First World War, truck transports played an increasingly important role, so that by the end of the 1920s the volume of goods handled had sunk to a manageable level.

Coal for the steam locomotives, the Neasden power station and the local gas works was brought in via Quainton Road. Other important goods were milk deliveries from the Aylesbury region to the London suburbs and food deliveries from the wholesaler Alfred Sutton & Son from Vine Street to Uxbridge. Fish deliveries to the Billingsgate market via Monument Station, operated jointly by the Met and the District , often caused complaints because the station entrances were in an "indescribably dirty condition". The District suggested a separate entrance for fish deliveries, but nothing happened. Traffic decreased noticeably when the GCR introduced road transport to Marylebone, but the fishing problem persisted until 1936. The LPTB gave the stench as the reason for stopping package transport on the trains on the ring line.

The Met initially commissioned private companies for road transport, but from 1919 it employed its own freight forwarders. In 1932, a year before the Met became part of the London Underground , the company had 544 freight cars. It transported 165,376 tons of coal, 2,517,980 tons of raw materials and 1,031,797 tons of goods.

Rolling stock

Steam locomotives

Concerns about smoke and steam in the tunnels led to the development of new types of steam locomotives. In 1861, before the opening of the first line, test drives took place with an experimental locomotive by John Fowler , nicknamed "Fowler's Ghost". It stored energy in heated bricks according to the heat storage principle, but was unsuccessful. For this reason the Met reached for the first passenger trains on broad-gauge locomotives of the Great Western Railway back of Daniel Gooch designed Tender - condensation locomotives the GWR Metropolitan class with the wheel arrangement 2-4-0. They were replaced by standard gauge locomotives of the Great Northern Railway until the Beyer-Peacock Met in Manchester received their own 4-4-0 locomotives. Its design is often attributed to the Met chief engineer John Fowler, but it is a further development of a Beyer locomotive that was built for the Spanish railway company Ferrocarril de Tudela a Bilbao . Fowler only specified the diameter of the drive wheel, the axle load and the ability to negotiate tight corners. In 1864, 18 of these locomotives were ordered, each with a name. In 1870 there were a total of 40 copies. In order to curb smoke development on the underground routes, coke was first burned, and from 1869 smokeless anthracite coal from Wales.

Between 1879 and 1885, the Met received 24 units of a modernized version of their previous locomotives. Originally they were painted light olive green with black and yellow stripes; the chimneys were clad with copper, the steam dome was made of polished brass . In 1885 the Met introduced a dark red paint. The color known as Midcared remained the standard color of the Met and was adopted by the London Passenger Transport Board as the line color of the Metropolitan Line in 1933 . When the Met classified its locomotives with letters in 1925, the first two series were given the designation A Class and B Class. During the construction of the M & SJWR northwest of Baker Street, those responsible were of the opinion that the locomotives would struggle on the incline, which is why in 1868 five locomotives were delivered to Worcester Engine Works with the wheel arrangement 0-6-0. However, it turned out that the A Class and B Class could pull trains with ease, which is why the Met sold the 0-6-0 to the Welsh Taff Vale Railway in 1873 and 1875 .

Additional locomotives were required for the expanding route network northwest of Baker Street. In 1891 the Met received four C Class (0-4-4) locomotives, a further development of the Q Class of the South Eastern Railway . In 1894 two D Class locomotives followed for trains between Aylesbury and Verney Junction. These were not provided with the condensation device that was required for the tunnel operation south of Finchley Road. In 1896 the Met built two E Class (0-4-4) locomotives in its Neasden depot and another in 1898 to replace the number 1 of the A Class, which had been damaged in an accident. Hawthorn, Leslie & Company built four more copies of the E Class in 1900/01. In 1901, four F Class (0-6-2) locomotives were added to cope with the increasing volume of goods traffic on the north-western trunk line, which differed slightly from the E Class. In 1897/98 the Met received two saddle tank locomotives (0-6-0), based on a standard design by Peckett and Sons. The Met gave them no classification and usually used them for shunting duties at Neasden and Harrow.

The electrification of the lines close to the center in 1905/06 made many of the locomotives superfluous. By 1907, 40 A Class and B Class locomotives had been sold or scrapped; by 1914, only 13 remained for shunting tasks, as work cars or for trains on the Brill Tramway . The Met needed more powerful locomotives for passenger and freight trains. In 1915 she received four G Class (0-6-4) locomotives from the Yorkshire Engine Company . Kerr, Stuart and Company delivered four H Class (4-4-4) locomotives in 1920/21, which reached a top speed of 121 km / h and were mainly used for express trains. For longer, faster and less frequent freight trains, the Met acquired six K Class locomotives (2-6-4) from Armstrong-Whitworth in 1925 ; these were conversions of locomotives with the 2-6-0 wheel arrangement that had been built in the Woolwich Arsenal after the First World War . The K Class was not allowed south of Finchley Road.

Two steam locomotives have survived: A Class No. 23 is on display at the London Transport Museum , while E Class No. 1 can be seen in the Buckinghamshire Railway Center by the former Quainton Road station.

Wagons

When it opened, the Met did not have its own wagons, so those of the GWR and later the GNR were used. The GWR used four-axle compartment wagons made of teak . In 1864, the Met received its first own wagons, made by the Ashbury Railway Carriage and Iron Company, based on the GWR design, but normal instead of wide gauge. They had gas lighting - two lights in the first class compartments, one in the second and third class compartments. Initially, the wagons were equipped with wooden block brakes, which were operated by hand in the driver's compartments at both ends of the train and gave off a characteristic smell. From 1869, the brakes of all cars could be operated with a chain. The actuation of this chain brake was sometimes abrupt and caused injuries to some passengers, so that it was replaced by non-automatic suction air brakes by 1876 . In the 1890s, the Met tested mechanical station indicators in some of the wagons on the ring line, which were triggered by a wooden tab attached between the tracks. The system was unreliable and was not approved for widespread use.

In 1870 Oldbury built some four - wheeled close - coupled wagons with rigid axles. After several derailments had occurred in 1887, the Cravens Railway Carriage and Wagon Company developed a new type of wagon called the Jubilee Stock for the north-western trunk line. The four-wheeled wagons with a rigid wheelbase were 8.38 m long and had gas lighting and suction air brakes from the start, and later they were also given steam heating . Another series of the same wagon type followed in 1892, but was withdrawn from service by 1912. According to an instruction from the Board of Trade , all wagons and locomotives had suction air brakes until May 1893. On the occasion of the 150th anniversary in 2013, a Jubilee Stock first-class car was restored for use by nostalgic trains.

In 1898 Ashbury built the first bogie wagons , followed two years later by Cravens and the Met (self-made at the Neasden depot). The new wagons were characterized by greater ride comfort; in all three classes they had steam heating, automatic suction air brakes, electric lighting and padded seats. From 1906 onwards, the Met converted some of the Ashbury bogie cars into electric multiple units. Today the Bluebell Railway has four Ashbury carriages, while a fifth Neasden car is on display at the London Transport Museum.

The competitive situation with the Great Central Railway on the north-western trunk line moved the Met from 1910 to use more comfortable wagons of the Dreadnought Stock type. She had 92 of these wooden compartment cars built, equipped with pressurized gas lighting and steam heating. In 1917 electric lighting replaced gas lamps and in 1922 electric heaters were added to generate heat even when an electric locomotive pulled the train. Usually a train consisted of five, six or seven cars. Sanding shoes on the rearmost and foremost carriages were connected to each other and to the electric locomotive via a bus line in order to avoid losing contact. Two train formations had a Pullman car with space for 19 people, in which food was available for an extra charge. They were the only car with a toilet. The Vintage Carriages Trust now owns three dreadnought cars.

Electric locomotives

After electrification, compartment car trains pulled by electric locomotives ran from Baker Street on the outer suburban routes, with the electric locomotive being replaced by a steam locomotive at an intermediate stop. The Met ordered 20 bogie electric locomotives with two different types of electrical equipment from Metropolitan Amalgamated Carriage and Wagon. The first ten with Westinghouse controls were first used in 1906. These "camel hump" locomotives with a centrally located driver's cab weighed 50 tons and had four drive motors with an output of 215 hp (160 kW). The second series from 1907 in the " boxcar " design had a control from British Thomson-Houston and weighed 47 tons; it was replaced by the Westinghouse type in 1919.

In the early 1920s, the Met placed an order with Metropolitan Vickers to convert the 20 electric locomotives. When work began on the first locomotive, it turned out to be impractical and uneconomical. The Met changed its order and now wanted new locomotives using part of the original equipment. The new locomotives were built in 1922/23 and named after famous Londoners. They weighed 61.5 tons, had four engines with an output of 300 hp (220 kW); With an hourly output of 1200 hp (890 kW), a top speed of 105 km / h could be achieved. Two locomotives from Metropolitan Vickers have been preserved: No. 5 " John Hampden " is on display in the London Transport Museum, No. 12 " Sarah Siddons " is operational and is used on nostalgic trips.

Electric multiple units

The Met placed its first order for electric railcars with Metropolitan Amalgamated in 1902, more precisely for 50 sidecars and 20 motorized cars with Westinghouse equipment. These saloon cars were put together in six-car trains and offered seats in first and third class. On this occasion, the Met abolished second grade. Access was via lattice doors at the ends of the wagons and the wagons were modified so that they could run as three-man units outside of rush hour. The Met and GWR acquired 20 six-car trains with Thomson-Houston equipment for the jointly operated route of the Hammersmith & City Railway. In 1904 the Met ordered 36 more motorized cars and 62 sidecars. Problems with the Westinghouse equipment meant that the Met redeemed the option for 20 motorized cars and 40 sidecars, but insisted on Thomson Houston equipment and had even more powerful engines installed. The more powerfully motorized three-car trains were used on the ring line before 1918. The lattice doors on the above-ground routes were perceived as problematic, so that by 1907 all wagons received vestibules. From 1911, the cars used on the ring line were given additional sliding doors in the middle to accelerate boarding and alighting.

Some of the Ashbury bogie cars were converted into railcars from 1906 by equipping them with appropriate driver's cabs, control devices and motors. In 1910, the Met had two motorized cars with driver's cabs modified at both ends. They initially operated as shuttle trains between Uxbridge and South Harrow, from 1918 on the branch line to Kensington (Addison Road) and finally from 1925 to 1934 between Watford and Rickmansworth. In 1919 the Met ordered 23 motorized cars and 20 sidecars. These were saloon cars with sliding doors at both ends and in the middle. They operated on the ring line as well as on the ELR to New Cross. In 1921 another 20 motorized cars, 33 sidecars and six first-class control cars were added, each with three double sliding doors on each side and running on the ring line.

Metropolitan Carriage and Wagon and the Birmingham Railway Carriage and Wagon Company built railcars with compartments for use between central London and Watford and Rickmansworth, respectively, between 1927 and 1933. The first order was for motor vehicles only; one half had Westinghouse brakes, controls from Metro-Vickers and MV153 motors. They replaced the motor vehicles with bogie trailers. The other motor cars had the same engines, but used suction air brakes and were combined with converted dreadnought cars from 1920/23 to form "MV" units. In 1929 the Met ordered the “MW” series, consisting of 30 motor vehicles and 25 trailers similar to the MV units, but with Westinghouse brakes. Another MW series was ordered in 1931, this time from the Birmingham Railway Carriage and Wagon Company. They formed seven 8-car trains, while the rest were used to extend the MW trains of the first series to eight cars. These cars had WT545 engines from GEC ; contrary to expectations, they did not work smoothly with the MV153 motor vehicles. After the Met became part of the London Underground, the MV cars were fitted with Westinghouse brakes and the GEC engines were better tuned so that they could run together with MV153 motor cars. In 1938 nine 8 and ten 6 units with MW wagons were given the new designation T Stock. A 1904/05 trailer car is in the Acton depot of the London Transport Museum and the Spa Valley Railway has two T-stock cars.

literature

- Alan Jackson: London's Metropolitan Railway . David & Charles, Newton Abbot 1986, ISBN 0-7153-8839-8 .

- John R. Day, John Reed: The Story of London's Underground . Capital Transport, St Leonards on Sea 2008, ISBN 978-1-85414-316-7 .

- Stephen Halliday: Underground to Everywhere: London's Underground Railway in the Life of the Capital . Sutton Publishing, Stroud 2001, ISBN 0-7509-2585-X .

- Christian Wolmar : The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground was built and how it changed the city forever . Atlantic Books, London 2004, ISBN 1-84354-023-1 .