City and South London Railway

The City and South London Railway (C & SLR) was a predecessor of today's London Underground , the underground railway of the British capital London . The first section of the route is the oldest underground railway in the world built in deep, drilled tubes and the first to be operated electrically . After its opening in 1890, it served six stations between the City of London and Stockwell over a length of 5.1 km , including crossing under the Thames .

The small diameter of the two single-lane tunnels limited the size of the cars. Due to the lack of windows, these were referred to as padded cells (" rubber cells "). The route was lengthened several times at both ends and finally reached a length of 21.7 km. It led from Camden Town north of the city center to Morden (at that time still in the county of Surrey ) and had 22 stations.

Although the C & SLR was heavily used, the company faced financial difficulties due to low fares and high construction costs. In 1913 she was part of the Underground Group . In the 1920s, extensive modifications were made to accommodate larger trains and to connect the line with the other underground lines. In 1933, the C & SLR and the other railways of the Underground Group came into public ownership. Today the route forms part of the Northern Line .

founding

On November 27, 1883, the London Gazette reported that a private initiative for the construction of the City of London & Southwark Subway would be presented to the British Parliament (by law, Parliament had to approve all privately financed rail projects). The initiator and engineer of the planned railway line was James Henry Greathead , who built the Tower Subway in 1869/70 and used the tunnel construction with shield jacking and cast iron segments planned for the CL&SS . The route was to begin at Elephant & Castle in Southwark , cross under the Thames and lead to King William Street in the City of London . The rails should be in two individual tubes 10 feet 2 inches (3.1 m) in diameter. The bill received Royal Assent on July 28, 1884, and became the City of London and Southwark Subway Act, 1884 .

Section 5 of the Act stated:

- The works authorized by this Act are as follows: -

- A subway commencing… near… Short Street at the… junction… with Newington Butts and terminating at King William Street…

- The subway shall consist of two tubes for separate up and down traffic and shall be approached by means of staircases and by hydraulic lifts.

(“The works authorized by this Act are the following: An underground railway starting ... at ... Short Street at the ... intersection ... with Newington Butts and ending on King William Street ... The underground railway shall consist of two tubes for separate traffic north and north to the south, accessible by stairs and hydraulic lifts. ")

In November 1886, five months after construction began, another private initiative was submitted to Parliament to extend the Elephant & Castle tunnels further south to Kennington and Stockwell . It came into effect on July 12, 1887 as the City of London and Southwark Subway (Kennington Extensions, & c.) Act, 1887 . The tunnels in this section were slightly larger than 10 feet 6 inches (3.2 m) in diameter. Before the railway line was opened, parliament passed another law that allowed it to be extended to Clapham Common . It was published on July 25, 1890 as the City and South London Railway Act, 1890 and also included the company's name change to City & South London Railway .

Drive and infrastructure

Like the Tower Subway, the C & SLR was originally intended to be pulled through the tube by means of a steel cable, similar to a funicular . A stationary machine that generated a constant speed should serve as the drive. Section 5 of the 1884 Act stated:

- The traffic of the subway shall be worked by… the system of the Patent Cable Tramway Corporation Limited or by such means other than steam locomotives as the Board of Trade may approve from time to time.

- ("Traffic on this subway is to be handled by ... the system of Patent Cable Tramway Corporation Limited or in any manner the Board of Trade may approve over time, excluding steam locomotives.")

The cables should be attached to the cable by clips. The clamps, in turn, should be opened and closed in the stations so that the trolleys can be detached and attached again. This should allow the cable to run uninterrupted and a station stop should not interfere with other trains on the route that use the same cable. The approved tunnel extensions showed the technical limits of the cable drive. Before a solution could be found, the cable company shut down. Due to the small diameter of the tunnels, the use of steam-powered trains was not possible, and the law explicitly excluded this possibility. The solution to the problem was the supply of electrical energy via a conductor rail under the train.

Although this type of drive had been tested in the previous decade and also introduced on a few short routes, the City & South London Railway was the first major rail company in the world to use electric drive. Electric locomotives from Mather & Platt were used on the route, which ran at a voltage of 500 volts and were able to pull several cars. At Stockwell a workshop and a power station were built on the surface. The route was initially accessed via a 2.8% steep tunnel that is now walled up. The rolling stock was pulled to the surface with a steam-powered chain winch until 1905, after which a hydraulic lift was used. The cars only drove to the workshop for general overhauls; they were parked in the tunnel. Due to the poor performance of the generators and the unreliability of the electrical energy at that time, the stations were lit with gas lamps.

There were different planning variants for the tunnels: The planning of a large tunnel that would have included both directional tracks was no longer pursued at an early stage because it was not included in the law for the construction of the line and was found to be too expensive. It was also assumed that the stability of such a tunnel would have suffered from its size. Two variants were also planned for the execution of the twin tunnels. Either a two-story tunnel or two parallel tunnel tubes should have been created. Simultaneously with the decision in favor of the electric drive, the latter variant was chosen, whereby a two-story tunnel was built during the crossing under the Thames.

Construction and opening

As the first section, two tunnels were built under the Thames at different times. For the construction of the further route, two access shafts were set up at the Borough and Elephant and Castle stations , from where the tunnels were driven in both directions. The southernmost section reached the Stockwell terminus at a maximum speed of up to 24 m / week . The tunnel tubes were lined with seven-part cast iron rings and sealed with tarred hemp and cement. To prevent the ingress of water, high air pressure prevailed in the shafts during the construction.

The Prince of Wales , who later became King Edward VII , officially opened the first section of the line on November 4, 1890. Scheduled operations began on December 18, 1890. The trains ran from Stockwell to King William Street , with stops at The Oval , Kennington , Elephant & Castle and Borough stations .

At the beginning the trains consisted of the electric locomotive and three cars. The carriages, which could accommodate 32 passengers, had benches arranged lengthways. Sliding doors at both ends led to platforms where entry and exit took place. Society was of the opinion that there was nothing to see in a tunnel anyway. For this reason, the wagons had no windows, only small glass slits high above the seats. Door guards drove on the platforms, who were responsible for opening and closing the barriers and called out the station names.

Since the cars were very narrow and caused claustrophobia in some passengers ( up to 72 people were often in them during rush hour ), they soon received the reputation of being “sardine cans” or “padded cells”. In contrast to other railways, there were no carriage classes or paper tickets. Instead, a standard fare of two pence was charged at the access barriers, regardless of the distance traveled. Despite the cramped conditions and competition from trams and horse-drawn buses , over 5.1 million passengers traveled by train in the first year of operation in 1891. In order to cope with the rush, the company soon deployed additional trains.

Extensions to Clapham and Islington (1890–1901)

| City & South London Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shortly before the opening, the C & SLR announced its intention to submit another private initiative to parliament. A new route was planned from the northern endpoint King William Street towards Islington. Due to the unfavorable location and insufficient capacity of the King William Street station, the extension should not be connected directly to the existing tunnel. Rather, a pedestrian connection was planned to enable transfers between the separate lines. Parliament rejected the initiative as it requested a link to the existing line. In November 1891, the C & SLR published a revised version of their initiative. The company had recognized the disadvantages of the King William Street station and only one year after the opening was planning a new tunnel section to bypass the problematic northern section.

The tunnels were to branch off near Borough station and follow a new route that would connect to London Bridge station . You should then cross under the Thames east of London Bridge and lead through the City of London to The Angel in Islington. The joint commission of the lower and upper houses had to deal with numerous other subway projects, which is why the extension of the C & SLR was only approved on August 24, 1893. The law passed included another initiative from 1893 to build the extension south to Clapham.

The construction of the two approved extensions was delayed because the financing was not secured for the time being and the plans had to be changed in individual points. The C & SLR brought three further initiatives in order not to let the already granted permits expire and to obtain additional permits:

- November 23, 1894: The 1890 Act was extended and a new access tunnel to King William Street Station was approved. Approved as the City and South London Railway Act, 1895 on April 14, 1895.

- November 22, 1895: Extension of the law of 1893 and changes to the planned station bank. Approved as the City and South London Railway Act, 1896 on August 14, 1896.

- November 26, 1897: Deadline extension of the 1896 Act, construction of siding at Clapham Common and sale of King William Street Station and the access tunnel to the proposed (but ultimately never realized) City and Brixton Railway . Approved as the City and South London Railway Act, 1898 on May 23, 1898.

The law passed in 1895 made it possible to rebuild the terminus at King William Street. The single-track station with a side platform was converted into a double-track system with a central platform in 1896 in order to temporarily remove the capacity bottlenecks. Almost four years later, on February 24, 1900, the station and the driveway were closed. The following day the northern extension with the stations London Bridge , Bank and Moorgate Street was opened . The southern extension with the stations Clapham Road and Clapham Common went into operation on June 3, 1900. Like the original Stockwell station and the rebuilt King William Street station, Clapham Road and Clapham Common had a central platform.

Construction progressed on the remaining section of the northern extension. The City and South London Railway Act, 1900 , passed on May 25, 1900, allowed the tunnel diameter at Angel Station to be widened to 30 feet (9.14 m). On November 17, 1901, the opening of the second part of the northern extension with the stations Old Street , City Road and Angel.

Extension to Euston (1901–1907)

Despite the technical innovations of the railway and the high demand, the C & SLR was not particularly profitable. The extensions built in quick succession, from which society expected a higher profit, were a great financial burden. The already low dividends continued to decline (2⅛% in 1898, 1⅞% in 1899 and 1¼% in 1900) and the company was accused of extravagance for abandoning the King William Street station. To circumvent the bad reputation problem and ease funding, the next initiative was brought before Parliament in November 1900 by a name separate company, the Islington and Euston Railway (I&ER), albeit in the person of Charles Mott had the same chairman. The planned route was to run from Angel Station (not yet completed) to King's Cross , St Pancras and Euston main stations. The I&ER initiative was just one of many projects brought in after the successful launch of the Central London Railway (CLR), which is why the committee of representatives from both Houses of Parliament needed more than a year to review the project.

It was not until 1902 that the bill could be dealt with in parliament. Resistance was offered by a competing underground company, the Metropolitan Railway (MR), which viewed the project as a threat to its own line between King's Cross and Moorgate. I&ER filed a petition requesting that the planned route be transferred to C & SLR if it was approved. The parliamentary committee overturned its earlier decision and rejected the proposal. In November 1902, the C & SLR submitted a similar initiative in their own name and at the same time requested the takeover of the concession of the now dissolved City and Brixton Railway (C&BR). A transfer to the planned, not yet built Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (CCE & HR) was planned under Euston station . The intent behind the acquisition of the C&BR concession was to build a new station under King William Street that would be connected to the C & SLR Station Bank and to the Monument Station of the Metropolitan District Railway (MDR). A third pair of tunnels should cross under the Thames, then run parallel to the C & SLR to Oval and finally lead to Brixton. This time Parliament approved the initiative, which became the City and South London Railway Act, 1903 , on August 11, 1903 . The rights of the former C&BR remained unused, but the extension from Angel was built quickly. From May 12, 1907 the trains ran to the stations King's Cross St. Pancras and Euston .

Cooperation and Consolidation (1907-1919)

Between 1890 and 1907, no fewer than seven new underground lines with more than 70 stations were built in the London area. There were also the Metropolitan Railway and the Metropolitan District Railway , which had been founded decades earlier. The individual companies competed with each other and were also in competition with electric trams and buses. In several cases, passenger estimates before the opening had proven too optimistic. The resulting lower income made it difficult for companies to repay the borrowed capital and distribute dividends to shareholders.

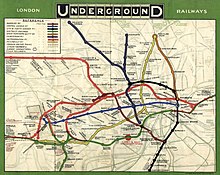

In an effort to work together to improve their tense situation, most of London's underground rail companies began to coordinate fares. In addition to the C & SLR, these were the Central London Railway , the Great Northern & City Railway and the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL, also known as Underground Group), which are owned by the Baker Street & Waterloo Railway (BS&WR), the Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway (GNP & BR), the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (CCE & HR) and the Metropolitan District Railway. From 1908 they began to market themselves together as "underground". The Metropolitan Railway and the Waterloo & City Railway (owned by the London and South Western Railway ) were not involved in this cooperation .

In 1912, the C & SLR introduced another private initiative in parliament and asked for the diameter of the tunnel tubes to be enlarged and to adapt it to the standard of the other underground lines. The enlarged tunnels should allow the use of larger and more modern trains. At the same time, the London Electric Railway (LER), a subsidiary of the Underground Group created in 1910 from the merger of BS&WR, GNP & BR and CCE & HR, brought in another initiative, which was the construction of a connection between the C & SLR station Euston and the CCE & HR station Camden Town provided. This connection was intended to enable CCE & HR trains to run on the C & SLR route and vice versa.

On January 1, 1913, the C & SLR was taken over by LER. She paid three of the C & SLR for two of her own shares. The resulting discount reflected the tense situation of the older company (on the same day, LER also took over the Central London Railway through a share swap, the ratio here being 1: 1). Parliament upheld the two acquisitions on August 15, 1913 with the City and South London Railway Act, 1913 and the London Electric Railway Act, 1913 . The planned extensions and the tunnel widening could not be tackled for several years because of the First World War .

Reconstruction and linking (1919-1924)

In February 1919, a few months after the end of the war, the C & SLR submitted a new initiative requesting an extension of the 1913 law. The corresponding new law was passed on August 19, 1919 as the City and South London Railway Act, 1919 . Although the building permit was renewed in 1920, the subway companies were not able to finance the work. Construction costs had increased significantly during the war years and the income did not cover the cost of repaying the borrowed capital. This changed in 1921 with the entry into force of the Trade Facilities Act, 1921. which allowed the UK Treasury to provide loans for public works construction projects as a measure to reduce unemployment. Thanks to this support, construction work was able to start with a seven-year delay.

The tunnels were widened by removing various cast iron segments from each segment, excavating the required free space behind them and reinserting the segments with additional expansion elements. The northern section of the C & SLR between Euston and Moorgate was closed on August 8, 1922, but the remainder of the line remained in service as the work took place during the nightly shutdown. When a train tore down a temporary support beam on November 27, 1923, the tunnel was filled with earth. The line was initially operated in two sections, but closed completely on November 28, 1923.

The Euston – Moorgate section reopened on April 20, 1924, along with the newly constructed link to Camden Town. The rest of the route to Clapham Common followed on December 1, 1924. Simultaneously with the widening of the tunnels, the stations had been modernized with longer platforms, new tiles and new lettering on the surface. Some stations received escalators to replace the original elevators.

Extension after Murden (1922–1926)

In November 1922, the C & SLR submitted a new initiative. It was planned to extend Clapham Common south to Morden . From Morden, the route was supposed to lead to Sutton above ground . Parliament passed the law on August 2, 1923 as the City and South London Railway Act, 1923 . Three months later, however, the C & SLR agreed with the Southern Railway (SR) that Morden should be the terminus of the subway. The above-ground part, the Wimbledon and Sutton Railway , was carried out by the SR as a conventional railway line. A new workshop was built south of the Morden station, and the C & SLR did without a connection to the railway line (less than 200 meters were missing).

The construction of the extension turned out to be far more expensive than the extension of other lines, as the area on the selected route was already built up over a large area. As a result, a large part of the route had to run underground. Since it was not a paved road, these tunnels had to be deep underground, although they only followed the main road out of town - which was also due to the purchase of land from undercuts as the only alternative. The tunnel construction was not only a financial problem, but also a static one, as layers of gravel soaked through made it much more difficult. The latter problem could be countered by appropriate tunneling methods and ultimately the financing could also be secured.

The tunnels were built similarly to the older tunnel sections, albeit with a larger clearance profile . Almost all the station buildings designed by Charles Holden with their distinctive domes were built above the stations on street corners, for which the existing buildings had to be demolished. In contrast to those of other underground lines, the reception buildings were not adapted to the surrounding buildings and integrated into the rows of houses, but instead stood independently above the station entrances according to their own architecture. The terminus Morden included a spacious transfer station to the local bus routes. While there was mainly a change in the flow of passengers in the already built-up area, the expansion had a huge impact on the development of the area around the new end point: Before the line was developed, there were a few small farms in Morden , some time after the opening there was already a cinema complex and numerous houses on the edge of the original settlement area under construction.

The extension after Morden went into operation on September 13, 1926, with the intermediate stations Clapham South , Balham (only on December 6), Trinity Road (Tooting Bec) , Tooting Broadway , Colliers Wood and South Wimbledon . Also on September 13, 1926, the line Charing Cross (now Embankment) - Kennington was opened, with Kennington receiving a second central platform. Thus the once separate route networks of C & SLR and CCE & HR were linked at two points. Both routes were marked with the same color on the route maps, but retained their original names for the time being.

Transfer to public ownership (1924–1933)

Despite the modernization of the C & SLR and improvements in other parts of the subway network, the individual companies continued to struggle to make a profit. Since the Underground Group had been owned by the highly profitable London General Omnibus Company (LGOC) since 1912 , it was able to use the profits of the bus company, which had an almost monopoly, to cross-subsidize the operation of the deficit subways. Due to the competition from numerous small bus companies at the beginning of the 1920s, LGOC's profits fell, which had a negative effect on the profitability of the entire Underground Group.

The Chairman of the Underground Group, Lord Ashfield , tried to convince the government to regulate local public transport in the London area. Several corresponding bills were drafted in the course of the 1920s. The main actors in the debate over the level of regulation were Lord Ashfield and Herbert Stanley Morrison , Labor MPs for London County Council (and later Foreign Secretary). Ashfield sought to protect the Underground Group from competition and to control the London County Council's tram network; Morrison, on the other hand, wanted to place the entire transport system under state control. After numerous unsuccessful attempts, at the end of 1930 a template was introduced that provided for the creation of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB). This public company was supposed to take control of the Underground Group, the Metropolitan Railway and all bus and tram lines in an area called the London Transport Passenger Area (roughly equivalent to today's Greater London with smaller adjacent areas). The LPTB was a compromise - public ownership, but not complete nationalization - and began operating on July 1, 1933. On that day the C & SLR and all other subway companies were liquidated .

→ For the history of the line after 1933, see Northern Line

Aftermath

The tunneling and electric propulsion technologies, first used by the C & SLR, influenced the development of subsequent subways in London. The C& SLR proved that an underground railroad could be built without purchasing expensive land to dig the just below ground tunnels for steam-powered trains. Instead, it was now possible to drill deep-seated tubes without affecting the conditions on the surface. The C & SLR thus served as a model for the construction of several additional underground railways in London - on a much larger scale than would have ever been possible with conventional construction. The smaller diameter and the lower position of the tunnel tubes brought some disadvantages - the size of the cars is limited and in summer the warm air cannot escape.

During the Second World War , the disused tunnels between Borough and King William Street stations were converted into air raid shelters . Entrances were on King William Street and six different locations south of the Thames (nine were planned). In the 1960s the tunnels were used to help vent the London Bridge station. All entrances (except at 9 London Bridge Street) were closed with concrete. Most of the six original C & SLR stations were rebuilt or later modernized as part of the renovation program in the 1920s. Only the Kennington station building was largely preserved in its original state, with the dome over the elevator shaft as the most striking part.

Rolling stock

In 1889 two prototypes of electric locomotives were built to test their operational capability. In locomotive 1 the motors were attached directly to the wheelset , in locomotive 2 the drive was via couplings. The clutch motor turned out to be too loud for the tunnels, so more locomotives were commissioned based on the first model, the design of which differed slightly. It was designed by Dr. Edward Hopkinson, they were built by Mather & Platt, the body came from Beyer-Peacock . The locomotives were relatively small because of the small tunnel diameter and only had four wheels. There was a door at either end of the cab, and the controls were on the side.

Each locomotive could pull three cars at a speed of 25 mph (40.2 km / h), but at full load they reached their limits on gradients. Braking was done with air brakes . At the beginning, the locomotives could not generate the compressed air themselves; it was pumped into containers at the Stockwell station. The locomotives were later equipped with compressors. A total of 49 locomotives were used: two came from Siemens , one built the C & SLR itself, and two were second-generation prototypes. Most of the locomotives, namely the 29 of the second generation, were built by Crompton & Co.

After the closure of the limited capacity King William Street station in 1900, the locomotives were able to pull four cars. Five-car trains were introduced in 1907. Trains with six carriages wrong during a few weeks to the temporary closure of the route in November 1923. Following the temporary widening of the tunnel diameter and the reopening came standardized railcar of the type 1923 tube stick used.

A locomotive (No. 13) and a first generation car have been preserved for posterity. These are on display in the London Transport Museum .

literature

- Antony Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes . Capital Transport, London 2005, ISBN 1-85414-293-3 .

- JE Connor: London's Disused Underground Stations . Capital Transport, London 1999, ISBN 1-85414-250-X .

- Douglas Rose: The London Underground, A Diagramatic History . Capital Transport, London 1999, ISBN 1-85414-219-4 .

- John R. Day, John Reed: The Story of London's Underground . Capital Transport, London 2008, ISBN 978-1-85414-316-7 .

- Christian Wolmar : The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground Was Built and How It Changed the City Forever . Atlantic Books, London 2005, ISBN 1-84354-023-1 .

- David Bownes: Underground-How the tube shaped London . Penguin Books, London 2012, ISBN 978-1-84614-462-2 .

- David Bennett: Metro - The History of the Subway . transpress Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-613-71262-8 .

Web links

- Literature by and about City and South London Railway in the WorldCat bibliographic database

- Clive's Underground Line Guides - Northern Line

- Description of King William Street station

References and comments

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 25291, HMSO, London, November 27, 1883, pp. 6066-6067 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ A b c Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 35.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 25382, HMSO, London, July 29, 1884, p. 3426 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 25649, HMSO, London, November 26, 1886, pp. 5866–5867 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 25721, HMSO, London, July 15, 1887, p. 3851 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 25995, HMSO, London, November 22, 1888, pp. 6361–6362 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 26074, HMSO, London, July 29, 1890, p. 4170 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 36.

- ^ A b Wolmar, The Subterranean Railway. P. 135.

- ^ Day, Reed: The Story of London's Underground. P. 44.

- ^ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. P. 134.

- ↑ Bennett: Metro. P. 22.

- ↑ Bennett: Metro. Pp. 22-23.

- ^ Day, Reed: The Story of London's Underground. P. 42.

- ^ London Railway Press: A station on the London electric light rail. In: Weekly of the Austrian Association of Engineers and Architects , year 1891, No. 3/1891 (XVI. Year), p. 27, center left. (Online at ANNO ). .

- ^ Exploring 20th century London

- ^ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. P. 321.

- ↑ a b c Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. Pp. 140-141.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 26109, HMSO, London, November 25, 1890, pp. 6519–6520 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 48.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 26226, HMSO, London, November 24, 1891, pp. 6349-6351 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 26435, HMSO, London, August 25, 1893, p. 4825 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 61.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 26625, HMSO, London, May 17, 1895, p. 2869 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 26769, HMSO, London, August 18, 1896, p. 4694 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 26970, HMSO, London, May 24, 1898, p. 3236 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ A b c Day, Reed: The Story of London's Underground. Pp. 46-47.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 86.

- ↑ Closed on August 8, 1922.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 95.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 96.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 111.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27422, HMSO, London, April 4, 1902, p. 2289 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 139.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27497, HMSO, London, November 21, 1902, pp. 7764-7767 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27588, HMSO, London, August 14, 1903, p. 5144 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ In the order of their opening these were: 1. C & SLR (1890), Waterloo & City Railway (1898), 3. Central London Railway (1900), Great Northern & City Railway (1904), Baker Street & Waterloo Railway (1906) , Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway (1906) and Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (1907).

- ^ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. P. 171.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. Pp. 282-283.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 28665, HMSO, London, November 22, 1912, pp. 8802–8805 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 28665, HMSO, London, November 22, 1912, pp. 8798-8801 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 28747, HMSO, London, August 19, 1913, p. 5931 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 31180, HMSO, London, February 14, 1919, pp. 2293–2296 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 31510, HMSO, London, August 19, 1919, p. 10472 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. Pp. 220-221.

- ^ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. Pp. 223-224.

- ^ Day, Reed: The Story of London's Underground. P. 94.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 32770, HMSO, London, November 24, 1922, pp. 8314–5315 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 32850, HMSO, London, August 3, 1923, p. 5322 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ a b Bowness: How the tube shaped London. Pp. 114-119.

- ^ Day, Reed: The Story of London's Underground. Pp. 96-97.

- ↑ Route map of the London Underground from 1926 ( Memento of the original from June 6, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. P. 204.

- ^ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. Pp. 259-262.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 33668, HMSO, London, August 3, 1923, pp. 7905-7907 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. P. 266.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 47.

- ↑ Connor: London's Disused Underground Stations. Pp. 10-13.