West end (novel)

Westend is the title of a 1992 novel by the German writer Martin Mosebach .

Course of action

As the title suggests, the action takes place in Frankfurt's Westend, which was built around the turn of the century, and focuses on Schubert and Mendelssohnstraße in the vicinity of the neo-Gothic Christ Church . Here are the fictional villas of the Labonté and Has families as the centers of the two contrasting narrative strands that repeatedly intersect with the grandchildren Alfred and Lilly. Its eighteen-year history, from the end of the post-war period, around 1950, to the impending dawn of 1968 is told in seven parts, generally chronologically with a focus on individual stages. The protagonists' memories are inserted. Together with the retrospectives, this creates a picture of the changes in the bourgeois urban area in the course of the 20th century. as well as its residents.

prehistory

Labonté family

The delicatessen and luxury food store "Wwe", which Alfred's great-grandfather Friedrich gave his children. Labonté «is sold after the early death of his son Wilhelm. The family's lawyer invested the assets for the heirs, who continued to live in the small villa built in 1897 on Schubertstrasse, with which the founder's unmarried daughters, Matilde (Tildchen), born in 1905, and Mi, ran a middle-class household with a cook , Miss Emig, finance and also maintain their unemployed nephew Alfred and his wife Stephanie.

After a number of unfortunate war and post-war experiences, Alfred finds himself in a difficult situation with no prospects: A broken school education, his deployment as a soldier, the stay in the camp as a defeated and beaten prisoner of war, "an inept [] and inglorious [] role [...] in the black market era ”, his“ inability to continue to work ”and his restless,“ brooding plan-making ”is followed by an unstable phase of life in changing relationships due to the“ surge of jealousy and hatred ”. On a sudden whim, he marries the uprooted Stephanie (Steffi) who, after separating from her family from Bohemia-Moravia, ended up in a reform home. "It [seems] to him as if he could join forces with the little plant for mutual benefit, as if they were both children of a forgotten, defenseless people who have found each other abroad and now the hopeless superiority of the society in which they are are guilty, easier to bear. ”His expectation is not fulfilled, to this“ next to him all to himself as in a bubble ”indifferent in the“ powerless flight of the moths ”and timeless in an unregulated daily routine to penetrate and enter from it To receive “echo”.

Has family

Compared to the Labontés, the Has family has a success story, which, however, already contains the story of failure. Ms. Has manages the assets inherited from her parents Olenschläger, including a a collection of paintings from the Kronberg School of Painting . She invests her money widely in real estate, some of which, like the family house on Mendelsohnstrasse, were destroyed by bombing in 1945, and with foresight in shares in a Swiss watch factory. Since her husband, a notary, is getting old early, her nephew Friedrich Olenschläger, called Fred, becomes her employee. Her son Eduard, just at the age of 24 Dr. doctorate in economics, went to Geneva as a volunteer two months before the start of the war and bought Degenerate Art removed from German museums at low cost as an investment in Basel : three pictures by Kirchner and a Klee . In this context he got to know the art dealer Guggisheim and the upscale style of dressing.

In 1945 the "Olenschläger property and property management" was founded, which should benefit from the reconstruction of the destroyed city. After his mother's death, Fred continued to run the business as guardian, and Eduard only as a partner, because he was concerned that the son would not be able to handle the property economically.

After his return from Switzerland, Eduard Has has big plans: When looking at the remains of his parents' house, “his mind's eyes are on the future. For him, the rubble [...] means nothing more than a building site, and this building site seemed too small for his project. ”Even as a“ follower of tradition, one always has to weigh anew what is dead and discarded and what deserves, to be passed on to the next generation. ”He does not want a reconstruction, but a new building for himself, but Fred, who practices the Frankfurt merchant virtue of“ not letting his own wealth shine through ”, is planning a six-story apartment building and only leaves it to his cousin the top floor. Eduard, on the other hand, prefers to demonstrate wealth and cosmopolitanism and drives a red Chevrolet , despite Fred's opposition.

In a conversation with Guggisheim about the pictures he had deposited in Switzerland, Guggisheim won him over to the idea of building up an Expressionism collection with his help . Has is also interested in his exotic wife, who is unhappy in her childless marriage. Guggisheim gives Dorothée and his customers the opportunity to get to know each other as a third party during a vacation trip. In the following years Dorothée travels back and forth between Basel and Frankfurt. When she becomes pregnant, however, her husband is not ready to take on the role of father, and she marries Has, who recognizes this development as an agreement among cultured people, which makes it possible to remain on friendly terms with the art dealer and collection advisor.

The service staff is also characteristic of the social image of the bourgeois Westend. In addition to Mrs. Emig, it is represented by the caretaker Mr. and the cleaning lady Scharnhorst, who came to Frankfurt from Silesia during the war , is instructed in the Has house and makes herself useful there. When a bomb fell on the roof of the building during an air raid, it climbed up with the help of the caretaker and removed the source of the fire. For this heroic deed, she rewards the owner with a certificate of residence in the basement, which she cannot use for long, as the house burns down soon afterwards. A year later, she quartered on the rubble property. In the meantime, she is housed in a former allotment area, which is used as a collection point for the scrap metal removed from the rubble. There she lived for a while with the scrap dealer Kalkofen. After his sudden disappearance, she returns to Mendelsohnstrasse with her baby Kurt and earns her living doing cleaning work.

Main story

First part: The Main

Alfred Labonté leaves the house on a rainy day in April to go canoeing on the Main . On the way he meets Eduard Has and talks to him about the impending birth of their children. In a faded-in review, you learn about their rivalry as young people. While Alfred dominated the reputation of the young people because of his unconventional behavior as a strong member of a gang and his sexual experiences, the situation was reversed in the post-war period. He and his sad wife lead a disordered life with no independent income. Eduard, on the other hand, expanded his lifestyle through his stay in Switzerland during the war and brought a suitable elegant partner to Frankfurt. Alfred becomes aware of his own situation through the contrast. He's disappearing from town. Since you can find his boat at a lock, the police assume that he capsized and drowned in the river. Six weeks later, he was arrested in a stolen car near Hanover . At the end of May, his wife Steffi dies giving birth to her son. The lawyer Dr. Paul Stahr settles the case: Alfred is settled with 70,000 marks, waives further rights and gives his son Alfred up for adoption by Mi and Tildchen. In the same year Dorothée gives birth to a daughter, Lilly. The childhood phase of the two is told in a very condensed way. While Alfred, the new life of the great aunts, is modestly cared for in the old villa according to her principles, Lilly experiences the tension between overheating and hypothermia in the upbringing of her father and mother.

The two strands of the family touch again when Lilly and Alfred attend the same class. Their one-sided friendship goes back to the time when he “lived under the spell of the» Knight of Cronberg when he moved to the Holy Land «.” And dreamed himself and the blonde girl into the picture []. "Right from the start, [] he assigned Lilly to another world." This is confirmed for him every day when she, who does not get along with class work as well as he does, is brought to elementary school in her father's red car and from there again is picked up and "[e] r is afraid of meeting Lilly in everyday life, because he feels [] that she then [is] not quite herself." Accordingly, the Has daughter plays in the fairy tale play before graduation from elementary school My Rautendelein the main role, but he is not, as he imagined, the knight, but a hare who once speaks to the princess: "Is your hair made of real gold?" Alfred will ask himself this question again and again over the next eight years. But Lilly noticed him for the first time when she found out during rehearsals that he was a Labonté.

Second part: the quake

This part tells about the next five years. A small earth tremor that caused a pipe crack in a house belonging to Olenschläger's administration on Schubertstrasse resulted in a decisive upheaval in Eduard Has's private life. During Dorothée and Lilly's vacation in Askona, in the apartment of the new tenant Etelka, who was deported by her husband, he investigates water damage with an emphasis on the first syllable, lime kiln, and this is how the woman with the artful hair bun looks and speaks impressed that he starts a relationship with her. For them, the generous Dr. Has the Redeemer from her simple life and a gift from a noble world into which she dreams of ascending to take Dorothée's place. On the other hand, the cleaning lady Scharnhorst is worried about the arrival of the lime kiln woman, who already believed she had covered her tracks because she did not want to share her son with his father, and is now justified in fear that the junk goods dealer might now abandon his in her neighborhood more often visit first wife and discover Kurt.

Third part: the house

The main topics are the new town planning, the change in the Westend and the conception of the apartment on the upper floors of the new Eduards and Dorothées building.

Has commissioned an old friend, the Viennese architect Szépregyi, with the design and construction supervision. He tells him and Dorothée his philosophy of "functional beauty". It becomes clear that he has “an egoism of such burned-out innocence” “that one involuntarily takes away from him that there is no more burning topic in the wide world than the principles and works of Carl Szépregyi.” So he unfolds increasingly to family friend and confidante Cari and invites them to his house in the mountain forest in Styria . Has spends with his mistress a few days, while Dorothée with Lilly and Guggisheim the Biennale of Venice travel.

The parallel plot follows the almost sixteen-year-old Alfred during his nightly exploration of the brothel district that was created by the dissolution of the old residential units, during his conversations with Etelka, whom he admired in the traditional knife shop Rötzel and in the Cafe der Tierfreunde , where she gave him, Mr. Alfred from the Neighbor house, describes her life's woes and vividly tells him what Has told her about Dorothée, Cari and Lilly. When incorporated are authorial information and Alfred's thoughts about the classmate Lilly, in the café Feuerbach writes off his homework because they preferred the work of straight-A students.

Fourth part: love

Has is at the height of the development of his double life. The relationship with Etelka receives a new financial foundation. When Kalkhofen notices that he has found a successor, he negotiates with Has about the rent payments and threatens a divorce. Has fears that Etelka's independence will put him under pressure and responds to the junk dealer’s demand that he be the beneficiary of the maintenance of his beloved, because he is satisfied with the situation of knowing his mistress is legally bound and does not think about leaving his representative woman separate.

The new apartment is being completed. The proud client discussed in detail the hanging of the pictures with Guggisheim and Szépregyi. The inauguration of the Great Gallery becomes a social event. Only Lilly criticizes the atmosphere in her study, in which one cannot concentrate. While Dorothée blames her daughter's learning behavior rather than a room for her bad grades, Szépregyi shows understanding for the high school student, sets up a study theory and offers to bring Lilly to Styria to regenerate.

Lilly is impressed by the radical modernity of Szépregyi's architecture, which exerts a fascination on her that Alfred cannot counter: “How richly orchestrated her soul [is] in truth, he [drives] her - such childlike mockery [Alfred's] for Despite - especially from Szépregyi. He opens [] her eyes to what she has always suspected [], and [proves] to her at the same time how meaningful such insights [are], because it [depends] on them whether the closet is on the right or left [... ] [stands] As deep as Szépregyi [penetrates] into dreams and hidden thoughts, one has [] to believe that he intends to create fairy, dramatic and lyrical rooms of almost absurd privacy. [...] and Lilly tells [] him her dreams ”. In his channel of the “moral-aesthetic cleaning work”, she judges the residents of elegant rooms with antiques and flower pictures as “noble skewers”.

Lilly receives tutoring from Alfred to improve her school performance. The two also visit each other in their parents' homes, which represent the tension in the question of structural Westend development and influence their children accordingly. While Alfred is urged by the aunts to collect signatures for the preservation of the Christ Church, Lilly describes this as backward zeal. But when the girl attentively looks at the picture of the knight in the Labontés stairwell, he feels the “premonition of future common ground”. The opaqueness of her feelings becomes clear when visiting the new Has apartment. She describes him to Szépregyi as her boyfriend and Alfred “is amazed [] at how much she [exaggerates] his role. He doesn't feel that he is so firmly anchored in this family circle [...] His relationship with Lilly [is], as you know, marked by a thousand uncertainties. "She shows herself in front of her parents and the guest who is keenly observing the supposed young rival so familiar with Alfred as never before that he hopes to meet her one day. But apparently Lilly only wants to challenge the man she admires, because the following night she visits him in his room.

The scenes in the fourth part illustrate the situation of the protagonists metaphorically: Has is at the height of its development before the already looming crash. The family is tanning high above the roofs of the neighboring houses on the sun terrace of the apartment styled by their friend Szépregyi. From here, in summer, the roofs of the old, not worth preserving villas, hidden behind chestnut leaves, in which the Labontés and the Etelka, who is in Has's mind, live, are not visible. In this backdrop of appearances and secrets, Lilly tried out her attractiveness as Lolita with the reform architect of the Frankfurt modern era, without being noticed by her father , by strategically using her school and tutoring friend, who was in love with her, in her game, while Has treated Alfred with benevolent neighborly interest whose falling family line, the grandfathers were still at eye level, can be reconstructed.

Part five: the night

The previous structures are becoming fragile. The protagonists get into development crises and look for new orientations.

Alfred now walks at night when he leaves the house in his father's tweed jacket that he left behind, “just go for it. He moves [] through the city like through a maze that hides a surprise in its midst.” He “looks for them Solitude and society at the same time ”. Toddi then takes him to the Bahnhofsviertel, for example in Ploog's beer parlors , "a significant expansion of Alfred's worldview". Here he meets a neighbor from across the street, Bundesbahnrat Rosendall. This will be his new nocturnal companion during the spa stays of his sick wife. Often he comes home drunk now, and the aunts fear that, like their nephew, whom he is increasingly resembling in appearance and in his "dreamy, juicy look", he will slip into a "stray". After the Has family left for the summer vacation in Austria to Széprecyi, Alfred continued his nightly strolling life. In the pub he finds warmth and closeness and comes across a familiar neighborhood: Rosendall and Etelka, comforting each other in their loneliness.

He is still biased towards Lilly when she, coming from the "cleaned zones" of Has's ambience, visits his aunts because he knows her opinion about the architectural style of the villa and its furnishings, but he is delighted that she is interested in Victor Müller's picture, his “youthful refuge”, also from a stylistic point of view and that she considers it the work of an Italian painter, and he now dares to attack Széprecyi's ideas and evaluations and calls him a show-off, after which she angrily leaves the house , but exactly at the time when the father's red car pulls up to pick it up: “She [is] an actress. Alfred [decides] to no longer pay attention to what she says [] but to what she [does]. "

Through a telephone conversation with Ms. Trumfeller, Dorothée learns that Eduard did not go to a meeting of the house and landowners' association in Cologne, but is in Schubertstrasse on property matters. She walks down this street and sees her husband with Etelka. She believes rightly that she has discovered his lover, who has been suspected for some time, but is not thinking of a separation: Since she is “certain” that she does not love Eduard Has, it means “no sacrifice […] for her by she [stays] with him. "She confides in Szépregyi, also tells of her strange dreams, and he becomes her interlocutor and psychoanalyst:" You hate Eduard as a man [...] you push him away, you hurt him in the core of his personality . "This interpretation of the background to the affair comforts her:" So it is herself who drove Has to Etelka []! […] I have him on my conscience […] She [stands] suddenly as the strong one, the unhindered one ”. Dorothée speaks to her husband about his relationship only when he is obviously suffering from Etelka's mood swings and even shows understanding for him when he willingly tells her about it. This brings the two closer together. After a long time they arrange a family vacation to Styria again, against the resistance of Etelka, who is not satisfied with her second role.

Part six: the money

Lilly and Alfred are now eighteen years old. The erosion of Has' position continues due to the changed situation on the real estate market and the interruption of his relationship with Etelka, while Dorothée reflects on her attitude towards Eduard and develops a new basis.

Vacationing together in Styria encourages both partners to think about their families through the distance. Dorothée secures her steadfast position vis-à-vis Etelka, although they speak little to one another. Has fantasized about an expansion based on the foundation of his marriage: In addition to Etelka, he is thinking of a second, younger lover. For the first time in a long time, the two of them spend the days together when their host takes Lilly with them on the hunt and she accompanies him on his trips to the office in Vienna. With this, "Szépregyi [...] as a comforter and mediator, as an entertainer and deputy has grown such an authority that Has now only found his father and husband's rights undermined" "[] [he] has to admit himself [...] in a self-tormenting manner that his friend Szépregyi [is] the more attractive leading figure for very young girls than he, the heavy-thinking citizen offspring sitting in an armchair, while Szépregyi [...] has something that is rather embarrassing for his age as a scout. "

After returning from vacation Has expect two unpleasant truths: The bubble Westend and the bad planning of the administration suggests itself: The assets of the administration is in houses that are to be declared a national monument and therefore achieve a meager return in terms of the rental price.

Ms. Scharnhorst reports in detail about Etelka's vacation relationship with Rosendall. He is disappointed with this betrayal and no longer visits his lover, but spends his evenings at home, which Dorothée astonishes, but confirms her cautious approach. After her reflections on vacation, she developed a new attitude towards Eduard and now has "the suspicion that she actually loves her husband after eighteen years of marriage."

Seventh part: death

The Labonté and Has families dissolve in turbulent developments. At the end of the novel, Alfred and Lilly stay behind in cleared houses.

Alfred made a tutoring appointment with Lilly on a Saturday afternoon and realized too late that Tildchen's birthday was to be celebrated at this time. He does not want to miss his chance to intensify the friendship, especially since he thinks he sees encouraging signs of this, and goes to her without informing the aunts. When he comes home that evening, he learns of his aunt's stroke, from which she dies a week later, and blames himself for his negligence. After her sister's funeral, Mi first changes the daily routine and then loses interest in her, and as it turns out, it is actually more of Tildchen's, adopted child. Apart from Alfred Zimmer, she dissolves the household and with it the “cosmos of the sisters” and withdraws to a Kronberg old people's home. Alfred now learns that he has not only been the owner of the house on Schubertstrasse since he was born, but that he also had a small fortune from the rent payments made by his aunts during the eighteen years.

Fred Olenschläger tries to gain access to the Has Collection in order to become creditworthy again for the administration's enterprises. He puts Has under pressure by submitting the management's financial claims to him as a shareholder who has exceeded his due share, e.g. B. Expenses for his apartment, picture purchases, cars, rent relief for Etelka ... The secretary has accounted for all his private expenses, and he now learns that he carelessly signed papers, v. a. he has contractually agreed to assume the planning costs of Szépregyis if the buildings do not come about. This declaration, written for his apartment, has not been put into concrete terms, however, and Olenschläger is now also referring to his own grandiose bad planning of large real estate complexes.

When Labonté's household liquidated, Has, who hopes to acquire the knight's picture in order to donate it to the Städel Art Institute , remembers the atmosphere in his mother's house. This situation fits his stunned zest for life: “Without the grace of pain that distracts from fear [] he experiences the horrors of death, the inexorable slipping of a loved one. And while Etelka [sinks] in front of him, the world that he [leaves] also becomes alien to him. Dorothée's tact, the villainy of Fred's cousin, Szépregyi's betrayal, Lilly's coldness, the slipping away from the collection [get] something unreal. "

He met Kalkofen, who would have liked to have taken over the good furnishings and recycled them. After a three-month break, the latter brings him back together with Etelka after Rosendall, in Etelka's words "[e] in very bad, a very small one", has proven to be unreliable. Business-minded, he helps his wife out of financial difficulties by buying the jewelry that Has had given him at a reasonable price because of its practical value and giving it to Has at a new price as a reconciliation gift for resuming the relationship.

Dorothée's attitude towards Eduard has changed since her vacation in Styria. She puts herself in his situation and traces the emotional deficits of their relationship as he must feel them. From this compassion she develops a newly experienced love for him. But she remains careful. "On the one hand [drafts] the direction for her future coexistence with Has, on the other hand [] she expects a new blow." And this she receives when she is on her way to house no. 23 with foreboding sees a man who has not come home with Etelka huddled together in a taxi: "Never before has she felt so abandoned."

But already with Guggisheim's phone call, which happened to follow the shock, she sees her situation calmer and focuses on the futility of her efforts at the moment of greatest exertion. In her first husband she sees a kindred spirit who endures the hopelessness of life in a detached, cultivated demeanor. The next day, Guggisheim travels to Frankfurt to appreciate the Expressionism images on behalf of Olenschläger, which he needs as security for a bank loan. The Eduard and Dorothée Has Collection may have lost its appeal for the art dealer since its construction has been completed, but a quick auction would sell it below value and the removal of individual works could reduce the coherence and cohesion. Since he has come to an understanding with Dorothée that she will divorce Has and return to him, he represents the interests of the co-owner, withdraws the pictures from Fred's legal claim and leaves them in a depot for his former and presumably future wife to secure legal clarification. Dorothée writes in a letter to her daughter, in which she primarily recognizes "a hare" that she is "welcome at any time." But now she wants to "think of [herself] first."

Shortly after Guggisheim and Dorothée's departure, Szépegyi appears in the abandoned house with Lilly, and Alfred, who learns this from Toddi, now realizes that they have a relationship with each other, which he sees as a compensation for his family status, which he perceived as less due to the unworthy death of his father . In addition, the two “cosmos […] shattered” by the dissolution of apartments and families: “There is no longer any distance between them […] and this idea [emanates] a flowing, calm happiness.” In one of his canoe trips He is faced with a dead child floating in the river Main, who symbolizes himself in the situation he was exposed to by his father at the time, and who is carried away by a tidal wave "into the night of the water." Early the next morning, Lilly calls him, behind Alfred senses that their farewell hides a cry for help. He immediately rushes to her “with a firm step”, as would be expected from the Kronberg knight, to protect her from the loudly cursing Szépregyi, and at the same time experiences Kurt Scharnhorst's fight to replace his mother on the stairwell.

Literary classification

Westend is a three-generation novel of the “ Buddenbrooks ” type with its focus on the parent company and the subject of the decline of a family , however Mosebach contrasts two families in ascending and descending career lines. After The Bed and Before A Long Night , The Blood Beech Festival and The Moon and the Girl , Westend represents the second stage of the writer's Frankfurt pentalogy .

structure

The plot of the Frankfurt epic, like other novels by the author that focuses on the city, such as A Long Night , can be historically and geographically determined with information on the location and street of the West End: it is divided into seven parts and generally takes place chronologically from the end of the Post-war period, real estate speculation and large-scale, functional urban planning up to the time of new beginnings: the impending house occupations and student unrest. The incorporated reviews capture the first half of the 20th century, the emergence of this bourgeois residential area, and thematize the images of man and values in comparison.

In this context, the author draws a portrait of this district, its streets and houses, as the scene of a heterogeneous society with sad personal situations and fateful and social dependencies. The assignment of the characters is, in addition to many networks, organized in two personal relationship fields. In keeping with the sequence of the eighteen-year-old main story, which is oriented towards the young protagonists, there is an Alfred - Lilly line with the motif of the search for a father figure, which expands into the Alfred - Lilly - Szépregyi chain of three.

This topic correlates with the existential basic situation of suspension or deportation, illustrated in the dead newborn child that father and son Alfred find at the beginning and end of the novel, with reference to little Moses , whose basket has sunk, in contrast to his rescue depicted in 2. Book of Moses , 2.1-10, which corresponds to the adoption of little Alfred by his great aunts. In a similar way, Victor Müller's picture of the knight Hartmut von Cronberg's departure for the Holy Land symbolizes the separation from the family and the reorientation. The two motifs of suspension and parting from the first part recur at the end of the novel like a cycle: Both Steffi and Lilly are dependent on help without parental support. Formally, Alfred's decision-making situation in the seventh part is similar to that of his father. Both leave the family villa with determination: “Today or never.” However, they have different biographies and head towards opposite goals on their way. Correspondingly, in Alfred's dream, the dead Moses child dissolves in the running water and the image of the knight in the stairwell is removed and transported to the museum. The further development of the protagonists remains open in the novel.

A second chain of people, analyzed in the next section, is formed through one-sided love relationships with separation-connection cycles: Scharnhorst - Kalkofen - Etelka - Has - Dorothée - Guggisheim.

Narrative form

The authoritative narrator does not present the plot in strict chronology, individual events are presented from the perspective of the people involved and often communicated in conversations or thoughts, for example Has's reflection on his situation after the apartment inauguration, or in retrospect after the end of the action, such as the The weeping Etelka involuntarily moved into her apartment rented by Kalkofen in Schubertstrasse from the perspective of the observing neighbors: “From the Hoffmanns' window seat, a man's hand could still be seen on the woman's full arm, the owner of this hand seemed to be the woman gradually wanting to pull out of the car. "Kalkofen contract negotiations in the administration and the story of the tenant and lover Has' can be seen with the" penetrating bird of prey look "of the strict secretary Trumfeller as well as in Kalkofen and Etelka's assessment. The reader follows Szépregyi's nerve-wracking room proportions, to name a further example, with the eyes of the builder who is endowed with an “innate talent for being an artist” and therefore worried about the health of his architect friend.

Whole passages are performed in double breaks: For example, Etelka tells stories in the knife shop Rötzel and in the Café der Tierfreunde Alfred in sometimes grotesque melodramatic-operatic presentations, as if she had been there herself, about the Has family, Dorothée's trip to Venice and above all What particularly interests her listener, about Lilly, i.e. episodes that she learned from her lover or from Szépregyi. The reader is informed about details of her affair with the married neighbor Rosendall through the report that the cleaning lady eagerly gives to her new landlord Has after his return from vacation, because she feels obliged to him after moving into the basement. For comparison, some of these experiences can also be experienced from a different point of view, e.g. B. Lilly's evaluation of the Venice-Styria trip with her mother or the lonely Etelka visits to a pub. People like the architect are sometimes controversially portrayed: by Alfred as an "old, skinny man" with tired eyes, by Lilly as a master, artist, hunter, soul researcher, tennis player ... In this way the narrator illuminates the characters, and at the same time their observers, in their various roles: Has in the assessment of the caretaker Herr, the cleaning lady Scharnhorst, Etelkas, Dorothées or the secretary Trumfeller. This creates a multi-perspective mosaic image.

The narrator not only reproduces the actions and thoughts of the people, but also explains and comments on them. He feels sorry for little Alfred: "But they [his weed bouquets] deserve more attention than they [get] in their jar on the kitchen window sill at Miss Emig's, because they [reveal] a very independent taste." He is guessing from: “Dorothée would have been surprised if she had read Guggisheim's thoughts.” Similar to an oral communication situation, the reader receives additional information, or a figure is protected: “But now you also have to say what Eduard Has, inside everything [is] prepared for a suicidal uprising, so under a spell. "or:" For the sake of justice, however, it must be stated that the actual hateful performance, as one probably suspects [], primarily [falls] on the Scharnhorst . "We can also fall back on an initiated we-community:" We know that on his return to Frankfurt, looking at the ruins of the house [...] of a New building [is] obsessed. "He wants to" experience himself creatively [...] ". The same applies to wisdom: "If we take seriously that everyone is capable of almost anything, we can hardly get around to outlining a cohesive character image that does a good job in everyday life." But the narrator occasionally admits not knowing the wishes of his characters completely. "Nobody can know what hopes Eduard Has has attached to the idea [] of spending six weeks in the presence of his daughter, but that he must see himself as deceived in this [] [is] obvious." Sometimes he also does not correct when his protagonists tell the untruth and leave the research to the reader, for example when Has Dorothée and Guggisheim want to appear younger and suggest a wrong year of birth.

Ironic distance

Ironic descriptions and comments prevent too strong empathy or even identification with individual people: “Etelka [is] basically gifted to hate and [lapses] under the lovelessness of Kalkofen into a quiet, whimpering weeping, rather than clenching her fists However, she always takes care [] to protect the skin around her eyes, and after a while ends the state of despair [] by [washing] her hair and toweling it dry [] as if it were the only one and the most important deed that still matters in her life. ”However, the narrator's attitude is not evenly distributed, the heroes of the novel, Aunt Tildchen and Alfred, are largely spared or the gentle irony is combined with obvious sympathy. Eduard Has's educational methods are different: “The paragraphs of this agreement [departure and collection of the daughter] were firstly that she could do what she wanted without giving any explanations, and secondly that he would take her to her appointments by car and pick it up whenever he feels like it. So Lilly [drives] up at some point in the big red car, kisses [] her father in front of her friends with the obedience of the jeune fille de bonne famille, who knows how to add a gentle religious note to tenderness, and [becomes] deep in the Picked up again at night, an effort that [earned her the reputation of being old-fashioned] without dampening her urge to move in the least. "

Historical background

An examination of the political history of the Hitler dictatorship and its crimes, and this is typical of the post-war period, does not take place, and the authorial narrator leaves it at references to paintings from Jewish possession or real estate belonging to owners who at some point disappeared. The characters are concerned with themselves, they lament their lost homeland and bombed houses, the soldiers who have not returned home, and concentrate on building a new city. This is how they come to terms with the past: demolition of the ruins, displacement, new concepts without historical traces.

Tradition or a new concept

Since the 1950s, the new business-like architectural style has been gaining ground in the Westend . During renovations, the turrets with the ornaments are removed. Art historians and state conservators declare “the architecture of the whole district to be worthless and ready to be demolished” and the progressive politicians are guided by the utopias of the new urban planners after the First World War . These prospects lead to a trade in old houses and land that is taking on feverish forms. The properties are either vacant or are rented cheaply during the transition period, e.g. B to Greek and Croatian workers or brothel operators. As a result, many long-time residents move away and offer their houses for sale: "The decay, its abandonment and neglect [combine] with the movement of sums, as if one suspects treasures buried in the bought-up front gardens." Protests of the population against the unscrupulous Speculations , which escalated into the Frankfurt house-to-house war in the 1970s , triggered pressure on the politicians and the quarter was placed under a preservation order, with the requirement to preserve the facade. Now the market is dead and house prices are falling rapidly.

The author distributes the different views on the new building to the protagonists of both families:

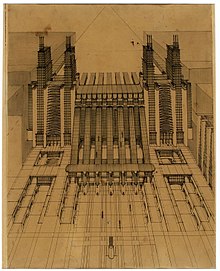

Fred Olenschläger - The urban planner

In the Olenschläger property management, Fred consistently represents the gigantic ideas. At the end of the First World War he “got to know the utopias of the new urban planners [...] drawings of cubic towers that border ten-lane streets with incessantly rolling cars, the glass bridges that connect the towers with each other high in the air and their moving walkways [transport] a never-ending crowd, the airports on the wide roofs, which could have taken in entire cities again, and he [can] never get rid of this inner image of an infinitely circling movement of crowds. "He plans to" roll up Schubertstrasse " and buys up old buildings with "backdrop architecture". “The planner lives in him, the real remodel of entire regions. [...] "Bauwurm" [...] there is no better word to name the secret unrest that [leaves] the old bachelor [...] awake in bed at night. […] Especially the Schubertstrasse [appears] before his eyes: no longer the street, but an elongated courtyard between glass, concrete-supported ships, which are connected with numerous bridges, a city within the city, with its own connection to the public Traffic system, with escalators moving against each other, pneumatic tube systems, thousands of people who [bring] typewriters to a steady rattle, a termite den in which it never has to be night []. "

Has is not the driving force in this development, but he is supporting it. In his search for a profile as a modern, cosmopolitan person, he discovers another form in the new architectural style that also corresponds to Dorothée's personality. In concrete terms, however, he does not care much about the planning of the administration, leaving the commercial decision on property acquisition to Fred and the accounting to the secretary Roswitha Trumfeller, who works with his cousin. He signs unconcerned while his thoughts linger on new acquisitions for his collection or ventures with Etelka.

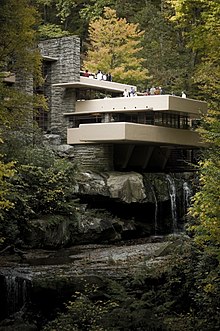

Carl Szépregyi - The new functional beauty

The Viennese architect Carl Szépregyi provides the philosophy for the new functional beauty of Frankfurt. He plans the buildings "from the inside out" in order to "read off the inner functions on the facade". He found his patron in Eduard Has, who commissioned him to build his apartment. Here he can demonstrate the "representation and function" of sober room design, different levels connected by metal stairs, spacious perspectives through open suites with whitewashed concrete walls and reflective black linoleum floors. The carefully proportioned, light-flooded rooms, the large and the small gallery, create the ambience for Has's painting collection, while the small kitchen expresses honest “functional [] beauty”. "Strictness and absoluteness in the implementation of his aesthetic plans" are his guidelines. In ironically described, self-tormenting detailed work, the architect tries to stage “living as a total work of art”. Eduard, Dorothée and above all Lilly are fascinated by his allegedly sensitive personality, who gathers their natural strength in the lonely landscape of Styria, and by his idea of removing everything that is left behind from the cityscape. To put it critically, metaphorically: “The departure that Szépregyi demands [] [sounds] violently like a tremor that [brings] entire streets to collapse. Above all, it [contains] for Alfred a threatening foretaste of Lilly's departure, which [seems] to be in preparation. "

Mi and Tildchen Labonté - traditional ways of life

As a contrast to Has' new building, the old Villa Labonté reflects the old days in the furniture. Images and forms of life preserved. In this home, Alfred is brought up with traditional structures and social forms and made aware of the upheavals in the environment. The great aunts teach their adopted child to distinguish linguistically precisely between “icebox” and “refrigerator”, “whore” and “woman who is being held out”. You give him education, z. B. Brecht's plays in the Frankfurt Schauspielhaus, in which, despite all the criticism of radicalism, they also discover a core of truth, or stylistics during the trip to Paris, where they want to sensitize Alfred: "What you see in Paris is all just imitation [...] In Paris there is 'no style of its own'. ”In the post-war discussion on new buildings, they take a pragmatic view: Today […] people openly admit that they no longer have a style and leave out everything that is imitated. That is not nice, but “a clean solution.” Your house and the furnishings, on the other hand, reflect the time of the rising middle class. They experienced the development of the Westend, moved into the “little villa with its Gothic ornaments and the weather vane” in Schubertstrasse as a new building (1897) and “had no ambitions, except one, namely to keep everything undamaged as it was handed over to them [ is]. "

Encouraged by his aunts, Alfred collects signatures against the plan to tear down the Christ Church, which was destroyed in the war, in order to build a “soup kitchen for students”. “In fact, he [cannot] imagine that Schubertstrasse would once again no longer run towards the large sky window of the Gothic arch. He [knows] what the world would look like if the quiet and yet tense, narrowing perspectives no longer flowed into this view of the otherworldly land. ”However, the aunts do not oblige their adoptive child to maintain the old facility. On the contrary: Before she moves out, Mi dissolves the household and gives Alfred, apart from his rooms, an empty house.

Analysis of personal relationships

A complicated dance of love between the protagonists, spanning generations and social classes, is incorporated into this process in a mixture of down-to-earth quality, for example with the cleaning lady or the scrap iron dealer digging through the rubble, market orientation and dreaming or the aesthetic aloofness of the art dealer, for whom a collection after its completion loses interest and is disbanded again. Most of the characters are looking for orientation and meaningfulness. In addition to the people in the chain of three Szépregyi - Lilly - Alfred already presented in other contexts, this is v. a. the series: Scharnhorst - Kalkofen - Etelka - Has - Dorothée - Guggisheim.

Scharnhorst

Even at the servant level, pragmatism is mixed with a loss of reality. On the one hand, the dwarfed cleaning lady Scharnhorst renounces "all of the well-read wisdom that citizens call education and with which they try to outdo each other, but [she appeals] exclusively to the experiences that eyes and ears [enable] her." on the other hand, she demands her right to live in the new house. Although in lucid hours she [sees] “the high degree of unreality” of her claim to a replacement for her apartment in the new building that was destroyed in the war, gives her the “[d] monthly letter to the“ administration ”[...] the strength of a powerful ritual. She feels [] her will when she [sends] such a letter, and she [grudges] her inflexibility. ”In some cases, she also achieves her goal, but only through Etelka's influence on Eduard Has, who lets her live in the basement in exchange for work . This ambivalence also determines her relationship with Kalkofen. Although he suddenly disappears and leaves her in the allotment house with no news, she is full of admiration for the strong man, who is not deterred by the material-oriented attitude of a scrap dealer even by the beauty of her successor Etelka: “He [is] a real man and can't be fooled by a pretty face. He [knows] women, [thinks] Scharnhorst with grim glee. He [knows] that one [is] just like the other. ”But she also knows the dangers. "Nothing can mislead her in her conviction that Kalkofen [is] a deity who [wants] to be worshiped from afar because she [burns] what [comes] close to her." Therefore she hides her child, however ultimately in vain, before the father.

Lime kiln

The dealer using the material requirements of the post-war period assembles his picture of reality as required. "Everything has to be put in order [...] I'll bring the boy into the yard, and you [Has] get along with Etelka again." Is his saying to organize a situation in his favor. When he has a new wife, he either goes into hiding, as with Scharnhorst, or shoves the former into an attic apartment on the grounds that “the woman needs air” and is interested in having a successor provide her. He appears to Has as his wife's understanding lawyer: “She says [] that she would have to suffer a lot from them. You did not respond to them, you would be opinionated and resentful. ”He discovered his fatherly love when he noticed that the strong son Kurt, who did not shy away from any physical work, was suitable for his business: as a pillar in the constantly suffering from failures“ Landsknechth heap his team ":" The boy belongs to me [...] big business awaits the boy. I have something to inherit. I've created values! ”Even the latent businessman in Eduard Has had to agree with the last statement.

Etelka

That the scrap dealer, based on Scharnhorst's characterization, married Etelka is astonishing at second glance. The 40-year-old wife of the scrap dealer impresses not only Has with her appearance. She is “as beautiful as a hairdresser”, as Herr Herr der Scharnhorst says, in full appreciation of her artfully tied hair knot. “When she [...] loosens the tightly twisted braid a little [], her back and shoulders [are] hidden in no time under floods of white-blonde, finely wavy curls. Etelka's hair [is] a fairytale splendor, and Alfred [...] loves [] her from afar for this hair from the very first day ”when she moves into Schubertstrasse 23.

But behind this surface is a dreamer. “Etelka has given little thought to the nature of the world so far. In the dark feeling of seeing the part of reality assigned to her, she [holds] to people who [concern] her directly and who [represent] the world for her. ”“ She occupies herself [] until she knows Has learns [], exclusively by exploring her life's misfortune. "" As a precious treasure of her character, she [possesses] an indestructible naivety that adds a poetry to her operatic appearance [] that makes this game succeed. "She has a great one narrative talent, to recite the story of her childhood with her aunt in Sopot , that of her sister, a singer with “wonderful love for Chopin ” or her tragedy with her “very passionate husband” before she said goodbye. According to her thoughts on the transmigration of souls, her sister was a lover of Chopin and the hangover of a singer by the name of Puccini was "actually [...] the creator of Madame Butterfly !" Her suffering as an outcast woman puts her in the limelight more melodramatically and not only draws Has in hers Bann, but also fifteen-year-old Alfred, addressed by her as Mr. Alfred, while shopping in the Rötzel household goods store. Following the pattern “a lady meets a gentleman and enters into a conversation with him”, she unfolds her story and then “suddenly emerges from her literary grief like from a small temple portal and [begins] to outline Kalkofen's meaning in impressive keywords. An organizer! An entrepreneur! An athlete! A business genius! A perfectionist! […] Alfred [it is] impossible in this description to recognize the rag collector to whom he sold the old newspapers as a little boy []. ”So Etelka is a“ gifted spokeswoman. This certainly does not mean the content of their speeches, on the contrary. Their volatility, their quarrels, their hints that one does not [understand], their imprecise memories and calendar wisdom distorted to the point of sweet or bitter [can] rob the listener's mind. It is rather her voice that captivates. ”In her attic room furnished with Capri souvenirs from Kalkofens warehouse, she unfolds her captivating, magical effect.

On his first long visit she immediately recognizes by its fine nature the origin of a prosperous world, to whose inner circle she would like to have access: “If you imagine Etelka Kalkofen as a soul floating in the air free of all fateful ties that only is looking for a place where she can materialize, so in her imagination there is no more inviting place than the one Dorothée [...] [occupies]. [...] Etelka [...] is always amazed the thought that this wrong-place life obviously belongs to the fate of Dorothée Has [] as it does to her own. [...] in everything that she suspects of the life of Dorothée Has in Mendelsonstrasse [], [...] [she] recognizes exactly what she longs for for herself []. "

She has time for Has, dreams of “sitting on Dorothée's sofa”, sees herself “wearing white every day” and always giving something to iron on and the donor of all these gifts, Dr. Has, namely, to stroke and caress when he [comes] home in the evening, in complete contrast to the cool Dorothée, who receives her husband by "like a cat [...] immediately [leaves] the room." "Etelka Kalkofen [on the other hand] [ is] a woman born to arouse expectations and at the same time equipped with everything to meet these expectations. "

Her relationship with Has, who often drives up in his red car and takes her to Wiesbaden with a new cloakroom, of course does not go undetected in the street, and Scharnhorst calls her a whore. Alfred's Aunt Mi is too simplistic, she differentiates from her nephew: “Frau Kalkofen is not a whore, but an endured woman” and thus affects Etelka's situation better, because it “worries [] […] the whole state of the irregular, the basically does not [correspond] to her own standards. ”But she has to come to terms with it because, despite her complaints, Has is not prepared to change his family situation and“ [s] he [feels] that he has sentenced her to an eternal wait and that he is stealing her life, namely her best years. "

Eduard Has

Eduard's double life with two different female characters reflects his ambivalent needs: on the one hand, he sees the Expressionist collection in open, light-flooded suites, in which his boyish-slender wife moves light-footedly elegantly in company as his life's work, and on the other hand, he loves Etelka's voluminous appearance in the cozy small attic rooms decorated with Capri compartments , gondolas and Chianti bottles .

As with his pictures, he has the attitude of a collector towards his women who wants to surround himself with the exquisite and thus to represent himself. After Dorothée, whose position as the wife and mother of Lilly is never up to him, showed himself to be an understanding wife to Etelka, he even thought of adding a second, younger mistress. Diplomatically, he comes to an agreement with the husbands of his mistresses who are willing to negotiate and who favor the arrangements. In his relationships he suffers from atmospheric disturbances. He seeks harmony and tries to compensate for the whims and weaknesses of women by generously giving them jewelry. For example, he wants to “see the possibility of ending Dorothée's disgruntlement by handing over a larger piece of jewelry.” Right from the start, he had a child-naive relationship with the financing of his projects; he apparently believed in the fairytale inexhaustibility of resources: “Dr. Has [...] wants [] to redeem funds, he [] has the trait of wanting to flow, whereby one has to think primarily of the Bayreuth and Salzburg Festival and the Expressionists, he [is] a baroque nature . ”In his complacency and egocentricity, he only realizes at the end that he has missed many developments and that he has long ceased to be the determining actor.

Dorothée

Her melancholy, already observable at Guggisheim, and a certain absent-mindedness, combined with a detachment, she also carried into her marriage to Eduard, which she decided to do when the art dealer, who had generously tolerated her relationship with Has until then, was unwilling to have her child take over.

Only when she meets her husband's lover Etelka does she reflect on the time when “she [...] [changed], like an animal does when the sounds of the wind [...] whisper that this is a good place . [...] Now retrospectively and under the influence of the newly acquired psychological interpretive skills, she would probably have seen the deeper reason for her move to Frankfurt in the paradox that Has was stranger to her than Guggisheim [...] the strangeness of Has left her unscathed and made coexistence possible , which for her did not have anything boring attached to it, but was an expression of her idea of naturalness. ”The narrator explains this line of thought and her decision to continue living with her husband despite her lover:“ Dorothée Has […] does not wish [] with anyone to exchange, and not because she would have been happy, but because, to put it philosophically, she cannot imagine human entities outside of her own. She did something with Has that doesn't satisfy her [], but it wasn't a mistake either. "

But Etelka's appearance causes a change in Dorothée. She is concerned about “the suspicion that she actually loves her husband after eighteen years of marriage.” Especially since their holiday in Styria together and Has's broken off of his affair, “something completely unexpected in Dorothée's nature has unfolded.” “You otherwise Such an indifferent relationship to time has given way to a fearful and at the same time happy alertness. The love for Eduard Has, which she discovered under such pain [], [has] become the main task of her life. "She no longer evades him," [s] he rather gladly and with friendly sadness sacrifices the pleasures of love loneliness when he unexpectedly comes into their company. ”The explanation for this is that Dorothée blames Has's“ unspeakable suffering ”, the petrification he was exposed to through her, that“ she pushed him back, probably without hurtful intent, but also without loving thoughts ”. In her sympathy, "as Eduard must have felt, [she] only needs to consider her own present condition."

When she discovers that her husband is resuming his relationship with Etelka, she is shocked. But shortly afterwards, after Guggisheim's call announcing his arrival, "[the] landscape that she overlooks [] [...] now lies in front of her in a different light." She sees in [her first husband] a soul mate, who already said goodbye to life and all hope during their marriage and therefore expelled them. In this attitude she now recognizes the wisdom of life, "[every joy], every higher beauty [can] only flourish in spheres in which people do not greedily attack one another." From this point of view "she experiences [] this love [ to Eduard] now more like a big lump that is tied on her back or perhaps even grown out of it [is] […] but […] is no longer in contact with Has himself and is therefore neither accepted nor rejected by him [can]. ”Her“ broken heart [] ”is the result of a development in the course of which she“ discovered new sensations in herself and did not shy away from the exertion of strength to develop appropriate behaviors […] her nature to turn inside out. But she overestimated her strength. ”She compares herself to a“ skinny boy ”who pulls a rickshaw with a“ stout, well-meaning European ”to the point of exhaustion, because he is afraid that the guest will get out otherwise dissatisfied, and finally notices that his car has long been empty, and "with one stroke [the] senselessness of [his] exertion" becomes aware. Consequently, she leaves the house in which everything, even her daughter, is "imbued with his [Has'] essence" and in which there is no room for her. She will separate from her husband and live again with Guggisheim, who feels the same way.

Guggisheim

Already at the first encounter with the "black-haired brownish girl", Guggisheim's exotic wife with Brazilian roots, born. Schlumberger y Silva, "but at least the father is Swiss", Has discovered, "that the dealer [has] managed to acquire a woman who fits into his environment of artistic lack of intent and accidental treasure [] as if she had created it herself." At the same time, he has “the feeling that she has a secret mourning that has nothing to do with Guggisheim and this exquisite studio [].” Her job is apparently to present the pictures to the customers. The dealer philosophizes to his guest about the South American women, as if he already suspected the interest of his future collector in his wife, they were “difficult to transplant. Time plays a completely different role for them than it does for us. These women have to take one bath every day. "

The Frankfurt resident's interest in the pictures and the art dealer's wife run almost parallel. Guggisheim apparently wants to win Has as a long-term customer and so hesitates to sell him “The Lady with the Black Hat”. He explains his idea of a collector and “the dealer he trusts” to him. The prerequisite for a collaboration is a concept that the dealer develops with “planning insight”. But the customer is not the dependent. “In truth, it is the dealer who wears the chains by linking his fate to the point of foolishness with an important collection.” Has and Guggisheim agree on such a cooperation in “mutual loyalty.” He provides the new collector with the desired painting in prospect, but he has to begin with Schmidt-Rottluff's "Two Boats in the Southern Harbor" to prove it. His rather secret advertisement for Dorothée leads almost simultaneously, surprisingly for Has, to the result he wanted, but hardly expected at the time. Guggisheim addresses the “foreign closeness - close strangeness” of the spouses and the apparently unfulfillable desire of his wife to have children. He explains: “We are like siblings […] we are made of the same cloth. We're so alike that we torment each other. But we will never leave each other. ”He suggests a trial week so that Dorothée can make the decision. Even after starting the relationship, she moves between Basel and Frankfurt for three months.

At the end of the novel, she returns to Switzerland. Comparable to the pictures, Dorothée has also grown in maturity for him [Guggisheim] after her “eighteen-year trip to Haus Has […] both socially […] and through the educational power of long-term misfortunes”. “He now feels like a pharaoh who, if he was looking for a bride of his own, was only allowed to look around among his sisters. Dorothée [is] such a sister. "

reception

In a newspaper interview with Martin Mosebach from 2007, the early history of reception is presented. Like other works published before the awarding of the Büchner Prize , the literary criticism hardly noticed Westend or criticized the language as the “mannered-mock narrative style of the penultimate turn of the century” and the author's attitude to tradition as “backwardness”. Similar evaluations can also be found in the later publications in the feature section that is split on this question.

Mosebach opposes this determination of the location, it is based on “misunderstandings”, he is not reactionary politically, but, in the sense of the Colombian philosopher and aphorist Nicolás Gómez Dávila , in a “belief in original sin, the imperfection of man, the impossibility To create paradise on earth ”, otherwise“ [re] actionary and revolutionary standpoints […] could touch ”, as with Büchner . He justifies his preoccupation with the fifties by saying that it was "artistically one of the most productive decades ever."

With increasing popularity, reviews increasingly appreciate the "Frankfurt Epic" as their main work, recognize the linguistic virtuosity of the author and praise Mosebach as perhaps the most important representative of the social novel , topics such as tradition and progress or people's search for cultural orientation in the Take up the context of our time and represent its position in the spectrum of German literature inappropriately.

The novel was selected for the 2019 reading festival Frankfurt reads a book .

literature

- Fliedl, Konstanze, Marina Rauchbacher, Joanna Wolf (eds.): Handbook of Art Quotes: Painting, Sculpture, Photography in German-Language Modernist Literature . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2011, Mosebach: p. 569.

References and comments

- ^ Mosebach, Martin: Westend . Munich 2004, p. 482. ISBN 978-3-423-13240-4 . This edition is quoted.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 482 f.

- ↑ Mosebach, pp. 11, 12.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 10.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 11.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 27.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 12.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 16.

- ↑ a b c Mosebach, p. 77.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 82.

- ↑ born ~ 1946, at least three years older than Alfred

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 224.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 220.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 226.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 242.

- ↑ a b c d Mosebach, p. 361.

- ↑ a b c Mosebach, p. 378.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 483.

- ↑ a b c Mosebach, p. 485.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 486.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 481.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 491.

- ↑ a b c d e f Mosebach, p. 517.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 559.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 539.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 554.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 555.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 600.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 597.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 648.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 670.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 809.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 755.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 760.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 770.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 777.

- ↑ a b c d Mosebach, p. 802.

- ↑ a b c Mosebach, p. 793.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 815.

- ↑ a b cf. Mosebach, p. 41.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 819.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 820.

- ^ Subtitle of the Thomas Mann novel

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 41.

- ↑ http://www.bildindex.de/htm

- ↑ http://www.europeana.eu/htm

- ↑ http://www.artothek.de/htm ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 9.

- ↑ cf. Mosebach, p. 495.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 74.

- ↑ a b c Mosebach, p. 424.

- ↑ Mosebach, pp. 350-375.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 489f.

- ↑ cf. Mosebach, p. 478.

- ↑ cf. Mosebach, p. 277.

- ↑ cf. Mosebach, p. 274.

- ↑ cf. Mosebach, p. 278.

- ↑ cf. Mosebach, p. 279.

- ↑ cf. Mosebach, p. 418.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 792.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 84.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 275.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 88.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 283.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 594.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 595.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 382.

- ↑ cf. Mosebach, p. 385.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 390.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 385.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 282.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 396.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 377.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 445.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 376.

- ↑ a b c Mosebach, p. 277.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 271.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 762.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 756.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 753.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 260.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 262.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 346.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 311.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 310.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 297.

- ↑ a b c Mosebach, p. 347.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 293 f.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 278.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 279.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 309.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 345.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 280.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 646.

- ↑ a b c Mosebach, p. 768.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 765.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 766.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 767.

- ↑ a b c Mosebach, p. 778.

- ↑ a b c d e f Mosebach, p. 779.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 109.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 110.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 113.

- ↑ Mosebach, p. 111.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 138.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 139.

- ↑ a b Mosebach, p. 157.

- ^ A b Volker Hage, Philipp Oehmke: "Reading is a laborious business". Interview with Martin Mosebach . In: Der Spiegel . No. 43 , 2007, p. 196-198 ( Online - Oct. 22, 2007 ).

- ↑ u. a. Ulrich Greiner and Ijoma Mangold in various Die Zeit articles