Toothworm

The toothworm is now a medical superstition . The mythical creature that lives in teeth has long been considered the cause of toothache and dental caries (as well as periodontitis and headaches). It is unclear whether the belief in this is based on an assumed "gnawing worm" (as a hypothetical explanation for the symptoms), on observations of encapsulated granulomas or the inflammatory changed tooth pulp (pulp dentis).

history

A Sumerian text (from around 5000 BC as Suddick and Harris falsely claimed in 1990) describes the toothworm as the cause of dental caries for the first time . When it came to dating, however, Suddick and Harris misinterpreted a publication by Hermann Prinz from 1945. If one follows Astrid Hubmann's dissertation, it can be seen that four sources, the oldest from around 1800 BC. BC dates to prove the belief in the toothworm. It is a sheet of Nippur .

A plaque discovered at Assur suggests that toothworm and toothache were treated differently, which might suggest an understanding of them as different diseases. From the library of the Assyrian king Assurbanipal (669-631 / 27 BC) comes the work of a Nabunadinirbu, which is entitled When a person has a toothache . Possibly it is a copy of a considerably older Babylonian text in which, in addition to the description of a treatment, a ritual incantation is of particular importance. In it the worm, probably a demon or an evil spirit, rejects the gifts of the highest god Anu, namely ripe figs , apricot and apple juice, and prefers the blood of the teeth. For treatment, emmer mixed beer, broken malt and sesame oil should be mixed and applied to the affected tooth. Basically, it was believed that rotten juices could give rise to worms anywhere in the body.

Also in ancient India (around 650), Egypt - here it is the Papyrus Anastasi IV, 13.7 (around 1400 or around 1200/1100 BC), Japan and China - there a sick tooth was a "worm tooth", But also among the Aztecs - there, for example, tobacco was put into the cavity - and the Maya , indications were found that the toothworm was the cause of tooth decay. The legend of the toothworm can also be found in the writings of Homer, and in the 14th century the surgeon Guy de Chauliac believed that worms caused tooth decay.

The main worm (Latin emigraneus ) thought to cause headaches was synonymous or related to the toothworm, which is sometimes divided into different (e.g. red, blue and gray) species.

The Compositiones medicamentorum by Scribonius Largus , the personal physician of Emperor Claudius , had a strong influence in the Old World . For treatment, he recommended smoking and rinsing, but also deposits and chewing agents as well as smoking with henbane seeds , which for this reason were called herba dentaria . He indicates that some worms are sometimes spit out during treatment. Since the henbane seeds, which got into the mouth with steam during smoking, begin to germinate, the white threads with a black head that could be seen in the process could be portrayed as "toothworms". So people continued to believe in the worm, but tried to accelerate the loss of diseased teeth by laying on worms. Pliny the Elder, however, did not believe in the existence of the toothworm, but in a similar healing effect.

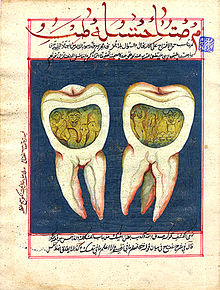

In the Arab world people believed in toothworms, referring to older traditions, as shown in the work of Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya ar-Razi , who viewed the relationship between body and soul as determined by the soul, as well as the works of Avicenna and Albucasis ' . 'Umar ad-Dimašqi, who taught in Damascus around 1200 , rejected the toothworm and, above all, the charlatanry that was driven by worms in his book The Chosen One about revealing the secrets and tearing the veil .

Around this time, Hildegard von Bingen also believed in worms, but recognized a lack of hygiene as the cause in her work Causae et curae . By rinsing with water, the livor , a deposit that could lay around the tooth and produce the dreaded worms, should be avoided. She recommended aloe and myrrh and coal smoke. Constantinus Africanus , who came to Salerno from Tunisia , made the local medical university famous in the early 11th century. He brought ancient knowledge and also the theory of humours to the north, but also confirmed the tooth worm.

From the time of the Enlightenment , the toothworm theory was largely assigned to the field of superstition by academic medicine. In 1728, Pierre Fauchard (in Le Chirurgien dentiste ) was one of the first dentists who did not see toothworms as the cause of tooth decay. It was not until the 19th century that various scientific theories about the development of tooth decay were developed. According to the chemoparasitären theory by Willoughby D. Miller (1890) were finally lactic acid bacteria until the 1960s regarded as the cause.

As a result, the specific plaque hypothesis developed , followed by a paradigm shift that led to the ecological plaque hypothesis . Due to several pathogenic factors, the hard tissue of the tooth is destroyed in several stages.

The belief in the toothworm (as well as in non-tooth related causes of illnesses thought of as “worms”) persisted in folk medicine into the 20th century. Until the end of the 20th century, the belief in the toothworm as a cause of pain was preserved in rural areas of China and was exploited by many quacks. Three of these scams from 1985, 1987 and 1993 are reported from Taiwan.

literature

- Liselotte Buchheim: The oldest toothworm text - in Babylonian cuneiform. In: Dental communications. Volume 54, 1964, pp. 1014-1018.

- Werner E. Gerabek : The tooth worm. History of a popular medical belief. In: Dental practice. Volume 44, 1993, Nos. 5-7, pp. 162-165, 210-213 and 258-261.

- BR Townend: The story of the tooth-worm. In: Bulletin of the History of Medicine. Volume 15, 1944, pp. 37-58.

Web links

- The tooth worm: History of the Folk Healing Faith Dissertation (PDF; 3 MB)

- The Worm and the Toothache Translated by EA Speiser, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Related to the Old Testament, edited by JB Pritchard (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 100-101, (Engl.).

- Toothworm: 3D model in the culture portal bavarikon

Individual evidence

- ↑ Werner E. Gerabek: Toothworm. In: Werner E. Gerabek, Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil, Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 1524.

- ↑ History of Dentistry: Ancient Origins , (Eng.)

- ↑ Richard P. Suddick, Norman O. Harris: Historical perspectives of oral biology: a series. In: Critical reviews in oral biology and medicine. Volume 1, Number 2, 1990, pp. 135-151, here: p. 142 ISSN 1045-4411 . PMID 2129621 . on-line. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ Hermann Prinz: Dental Chronology - A Record of the More Important Historic Events in the Evolution of Dentistry. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia 1945, p. 7.

- ↑ Astrid Hubmann, The Toothworm. The history of a folk medicine belief dissertation, 2008, p. 17.

- ↑ It is said to be under the signature tablet 55547 in the British Museum in London (Arthur Bulleid: The Microbe Hunters , in: Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. Section of Odontology, 47, 1953, pp. 37-40, here: p . 39).

- ↑ Astrid Hubmann, The Toothworm. The history of a folk medicine belief dissertation, 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Werner E. Gerabek: Toothworm. In: Werner E. Gerabek u. a. (Ed.): Encyclopedia of medical history. 2005, p. 1524.

- ^ Jörg Riecke: The early history of medieval medical terminology in German. Volume 2: Dictionary. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York, p. 532. ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Werner E. Gerabek: Toothworm. 2005, p. 1524 a

- ↑ Astrid Hubmann, The Toothworm. The history of a folk healing belief Dissertation, 2008, p. 26. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ↑ Werner E. Gerabek: Toothworm. In: Encyclopedia of Medical History. Edited by Werner E. Gerabek, Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil and Wolfgang Wegner, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin and New York 2005, p. 1524

- ^ WD Miller (1853-1907): The Micro-Organisms of the Human Mouth (unaltered reprint of the work printed in Philadelphia in 1890). S. Karger: In: Journal for general microbiology. 14, 1974, pp. 84-84, doi: 10.1002 / jobm.19740140117 .

- ^ PD Marsh: Dental diseases - are these examples of ecological catastrophes? In: International journal of dental hygiene. Volume 4 Suppl 1, September 2006, pp. 3-10, ISSN 1601-5029 . doi: 10.1111 / j.1601-5037.2006.00195.x . PMID 16965527 .

- ↑ Elfriede Grabner: The "worm" as a cause of disease. South German and Southeast European contributions to general folk medicine. In: Journal for German Philology. Volume 81, 1962, pp. 224-240.

- ↑ Cf. also Gundolf Keil: The fight against the earwig according to the instructions of late medieval and early modern German pharmacopoeias. In: Journal for German Philology. Volume 79, 1960, pp. 176-200.

- ↑ Helmut Kobusch: The toothworm belief in German folk medicine of the last two centuries. Philosophical dissertation Frankfurt am Main 1955.

- ↑ TL Hsu, ME Ring: Driving out the 'toothworm' in today's China. In: Journal of the history of dentistry. Volume 46, Number 3, November 1998, pp. 111-115, ISSN 1089-6287 . PMID 10388453 .