Second Thule expedition

The Second Thule Expedition Knud Rasmussen 1916-1918 the interdisciplinary study of North Greenland served between the St George's Fjord and the DeLong Fjord . The expedition achieved its scientific goals, but was overshadowed by the deaths of two participants, the Greenlander Hendrik Olsen, who did not return from a hunting trip, and the Swedish biologist Thorild Wulff , who died of hunger and exhaustion on the way back.

prehistory

In 1910 Knud Rasmussen founded the trading post "Thule" in Uummannaq near Cape York in North Greenland. He wanted to enable the polar skimos living in the region to continue their trade in skins on fair terms after the end of Robert Peary's regular presence for two decades . At the same time he wanted to use the station as a starting point for expeditions of an ethnographic and geographical nature, for the financing of which the profit generated was used.

The coastline of Greenland was almost completely known at that time. The last unexplored areas in the northeast of the island were mapped by the Danmark Expedition in the years 1906-1908. There was still some uncertainty in the north, where the coastlines of the fjords in what is now Knud-Rasmussen-Land were only roughly mapped and around Peary-Land , which was viewed as an island separated from Greenland by the hypothetical Peary Canal. Rasmussen decided to explore the area more closely in 1912 on his First Thule Expedition . He had to change his plans at short notice when it became known that Ejnar Mikkelsen and Iver Iversen (1884–1968) were missing from the Alabama expedition in northeast Greenland. Rasmussen felt obliged to rush to the aid of the two.

Relying entirely on the travel techniques of the polar skimos, he crossed the ice sheet with Peter Freuchen , his partner in the operation of the Thule station, as well as the Greenlanders Uvdloriaq and Inukitsoq, and searched in vain for the missing in the area of the Danmark and Independence Fjords . The expedition discovered that the Peary Canal does not exist and that Peary Land is part of Greenland, but there was no time to explore the fjords on the north coast. An attempt to make up for this in 1914 had to be stopped after the expedition leader Freuchen was injured when he fell into a crevasse . Rasmussen had not given up on the project and put it into practice from 1916 with the Second Thule Expedition.

Expedition destination

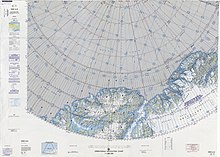

The aim of the interdisciplinary expedition was to explore and map the coastal areas in northern Greenland between the Saint George Fjord and the De Long Fjord. One focus was the search for traces of settlement of prehistoric Eskimos. Rasmussen hoped that this would provide information about the route on which the ancestors of today's Inuit had settled in Greenland. In addition, geological investigations should be the focus. It was also planned to keep a careful meteorological diary and to create botanical and zoological collections.

Attendees

Knud Rasmussen originally intended to carry out the expedition with Peter Freuchen as cartographer and the geologist Lauge Koch , who had been recommended to him by Hans Peder Steensby . But he changed his plans when he met the Swedish botanist Thorild Wulff, who eventually took Freuchen's place. Koch then also took over the cartographic work. The main expedition in 1917 had the following seven participants:

- Knud Rasmussen, ethnographer and expedition leader,

- Lauge Koch, geologist and cartographer,

- Thorild Wulff, botanist,

- Hendrik Olsen (1884–1917), West Greenlander who had already participated in the Danmark expedition,

- Ajako, Nasaitsordluarsuk and Inukitsoq, dog sled drivers and hunters.

Rasmussen insisted that everyone except the leader had the same position during the expedition, so that there were no differences in rank between the Europeans and the Greenlanders.

Preparation, equipment and funding

During his expedition, Rasmussen again largely relied on the techniques of the polar skimos, supplemented by rifles, ammunition, Primus stoves , petroleum and tools. The provisions brought with them, especially narwhal and walrus meat , which were bought in the various settlements of the Polareskimos, were measured in such a way that they would last two months or for the way there to the Nordenskjöld Fjord. For the return trip, only 130 pounds of pemmican were earmarked for the dogs. Rasmussen insisted on being able to feed men and dogs by hunting seals and especially musk oxen . He was aware of the risks of such an approach. However, the large ice-free areas marked on the American maps of the area to be visited gave him the confidence that the concept would work. During the first stages of the journey, additional sledges should accompany the expedition and gradually turn around, the last at Thank God Harbor. The seven men would then move on with six sledges, in front of which 72 dogs would be harnessed. The funds required came from the profits of the Thule station.

The expedition was only equipped with the most essential scientific instruments: a theodolite , three aneroid barometers , a boiling barometer for height measurements , a maximum and a minimum thermometer , various alcohol and mercury thermometers, an anemometer , a hygrometer and something for soaking and drying plants was needed.

Rasmussen, who had not had any academic training himself, sought contact with scientists before the trip. A scientific committee was founded, which consisted of the zoologist Hector Jungersen (1854-1917), the polar explorer Johan Peter Koch , the mineralogist Ove Balthasar Bøggild (1872-1956), the ethnographer Hans Peder Steensby and the botanist Carl Hansen Ostenfeld .

course

Melville Bay

Rasmussen and Koch left Copenhagen on April 1, 1916 on board the steamship Hans Egede . When they disembarked in Godthåb on April 18th, they realized that the weather conditions were difficult for a trip to North Greenland. A mild winter and an early spring ensured that there was neither solid winter ice nor open water. So the decision was made to postpone the expedition to the north coast of Greenland by a year and to take a more detailed land survey of the Melville Bay , which had only been roughly mapped until then . If you wanted to find favorable ice conditions there, time would hurry. Rasmussen, Koch and Tobias Gabrielsen (1878–1945) from Greenland, who had belonged to Johan Peter Koch's sled team on the Danmark expedition, traveled day and night by boat and dog sled. On June 4th, Kullorsuaq , the northernmost settlement in West Greenland, was reached. Melville Bay was explored from June 4th to 17th. Lauge Koch managed to map the entire 500 km long coastline. Meanwhile, Rasmussen examined the remains of earlier settlements and identified the ruins of more than 50 winter houses. He made detailed maps of the most important settlements.

Thule

From July 1st to October 1st, ruins of the Eskimos were found in the vicinity of the Thule trading post at Uummannaq . In addition to Rasmussen and Koch, Peter Freuchen was involved. A map with the remains of 60 houses as well as numerous graves, tent rings and meat pits was laid out. With George Comer , the Eislotsen the schooner George B. Cluett , who while trying to Crocker Land Expedition to pick from Etah in the home, in the North Star Bay has been frozen for two years, they dug a large midden of , a prehistoric rubbish heap. The bones found in it showed the importance of hunting bowhead whales for the people of the Thule culture , as it was later named after this site.

Another ship, the Danmark , came to Thule Station in the summer . This was also on the way to the Crocker Land Expedition, which was stuck in Etah . On board was the Swedish botanist Thorild Wulff, who strengthened the expedition team as a proven expert on the Arctic flora. In winter the expedition participants practiced sledding. Several trips led back to Melville Bay, where the work started in the spring was completed.

To the fjords on the north coast of Greenland

The expedition left Thule in two groups on April 5 and 6, 1917. Sleighs were rented and meat was bought in the residential areas along the way. Rasmussen had also ordered kamiks and mittens, which were now received. On April 9, the expedition set miz 27 carriages and 354 dogs in Neqi on. The next day she stopped in Etah at the house of the Crocker Land Expedition, which had to be extended to three days because a storm prevented her from continuing her journey.

Rasmussen followed the Nares Strait on the way there . On the wide ice foot at the edge of the Kane Basin , the sleds made good progress at first. On April 20, the 100 km wide front of the Humboldt Glacier was bypassed on the lake side on the way to Washington Land . On May 1, the men stood at the grave of Charles Francis Hall , who had died in 1871 after having advanced as far north as no one before him. Here Rasmussen sent back the last companions with the rock samples that Koch had collected up to then. The seven men were now making difficult progress, because ice pressings had pushed large floes onto the ice foot of the coast, so that it could usually not be navigated. On May 7th, the Saint George Fjord was crossed and Dragon Point was reached. The expedition had now arrived in its destination area.

Half of the provisions that were carried with me had meanwhile been used up. A depot was formed from the rest so that it would be available for the return journey across the inland ice, because hunting would no longer be possible here. Only three daily rations were taken with them for the men and a single meal for the 70 dogs, which were in poor condition due to the exertion of the past weeks and the lack of luck in the hunt. Two sleds were also left behind. The primary goal was now a supply of fresh meat. Only then could the research work be started. After crossing the frozen Sherard Osborn Fjord, 19 musk oxen were shot on the Nares Land peninsula . The expedition pitched their camp here until May 17th to give the dogs their strength again. Meanwhile Koch and Inukitsoq explored the Victoria Fjord. On May 18, Rasmussen, Koch and Ajako returned to Dragon Point and mapped the Sherard Osborn Fjord. The other four moved on to Nordenskiöld Fjord to hunt there as a precaution.

Rasmussen's group only met the other expedition members at the mouth of the Nordenskiöld Fjord on May 30, held up by Koch's febrile illness. While Rasmussen, Koch and Ajako explored the fjord, the others moved on towards DeLong Fjord. The narrow coastal strips of Nordenskiöld Fjord consisted of bare rocks. The hinterland was glaciated. The lack of food meant that more and more dogs had to be slaughtered and fed to the others. On June 4, Rasmussen's group discovered a still unknown large fjord leading eastwards, which was named J. P. Koch Fjord. On 14./15. June the group moved further north. One day later we met the second group, who had already lost many dogs. The lack of game had turned them back before they reached DeLong Fjord. When it was possible to kill a seal and a number of small game, Rasmussen decided to continue the expedition by exploring the DeLong Fjord. This turned out to be a branched fjord system. From the mountain Thule Fjeld on the island Hanne Ø, about 10 kilometers within the DeLong Fjord, this was roughly measured and sketched on June 21. With that the expedition had done its job. The way back to Thule lay ahead of her.

The way back

The thaw that started now made the return journey very difficult. There was now wet snow on the sea ice, which increasingly turned into ice water. Although the men drove 12 to 18 hours a day, they only got 15 to 16 km each. Fortunately for her, the weather improved so that the sun could repeatedly dry the wet clothes. The meat supply remained critical. Even if the seal or muskox hunt was successful, the men could not over-load the sledges if they wanted to move forward. The meat had to be consumed on the spot. As of June 28, the two groups were reunited. At that time the expedition still owned 21 dogs. After crossing the Sherard Osborn Fjord, Rasmussen, Ajako and Inukitsoq drove their sledges across the sea ice to the edge of the Daniel Bruun Glacier, which was to be used to climb the ice sheet, and the others went overland to the same place and tried to hunt hares or musk ox. When Hendrik Olsen from Greenland did not arrive at the agreed meeting point, the others had to travel on after a four-day unsuccessful search for the missing person. In a stone man they left him a message stating which way they would take. The island on which he was last seen was named Hendrik Ø by Rasmussen .

The Daniel Bruun Glacier turned out to be a firn that was separated from the inland ice by two deep and snow-free valleys. Overcoming this cost the men a lot of energy and time. The ice sheet was not reached until August 10th. The last provisions were consumed on August 21, and the last dog was slaughtered on the 25th. That day, the expedition left the ice sheet near Cape Agassiz in the east of Inglefield Land . It was now 250 km to Etah. Above all Wulff, who already suffered from both malaria and syphilis , was not able to tackle the route immediately. It was decided that Rasmussen and Ajako would get help from Etah, while the other four would head to a lake near Cape Russell after a few days of rest. After only five days, on the evening of August 30th, Rasmussen came to Etah. The auxiliary sleds were packed the following day, and on September 1, six men with five dog sleds left the residence. They met Koch, Nasaitsordluarsuk and Inukitsoq on September 4th. At his own request, they had left the exhausted Wulff, who complained of heart and stomach pain and hardly ate anything from the hare shot, on August 29th.

After recovering from the hardships of the past few months, Rasmussen went to Thule to prepare for wintering. A first attempt by Ajako in September to get to Wulff failed because of the heavy autumn storms. In October Koch, Freuchen and Ajako returned to Cape Agassiz, but were unable to find and bury Wulff in the dwindling daylight and freshly fallen snow. Freuchen was convinced that he would have regretted his decision and tried to follow his comrades. The collections and diaries that were left behind were recovered.

Results

From a scientific point of view, the Second Thule Expedition was successful and yielded significant results. Melville Bay and most of the fjords on Greenland's north coast have been mapped. On the north coast 40 latitude observations, about 80 azimuth determinations and 40 longitude determinations were made. About 150 heights were determined trigonometrically. The result was that numerous corrections could be made to the rough maps of North Greenland that had been available up until then. The area turned out to be much more glaciated than expected - one reason for the expedition's mostly unsuccessful hunting. The discovery of the large J.P. Koch fjord was a surprise.

Koch collected numerous minerals and fossils and made a geological map of the areas visited. His most important result was the discovery that the Caledonian Mountains , which run from Ireland and Scotland via Norway and Spitsbergen , continue in northern Greenland - and thus west of the Atlantic.

Rasmussen found nine former settlements between Etah and the Humboldt Glacier and another north of the glacier on Benton Bay. He was able to identify the ruins of winter houses and measure some of them. Regular excavations were not possible because of the extreme cold in April. He also found a large number of tent rings, meat pits and fox traps made of stones (so-called uvdlisatit ). The ruins of the winter cottages on Benton Bay were the northernmost discovered by the expedition. Because no tent rings, fire places or other traces of earlier settlement could be identified north of it, Rasmussen concluded that the settlement of northeast Greenland could not have taken place over the northern tip of Greenland, but only over Cape Farvel in the south. That Rasmussen was wrong was only revealed by the findings of Eigil Knuth's Peary Land expeditions after the Second World War . They prove that both the Eskimos of the Thule culture (as well as those of the earlier Independence I and Independence II cultures) immigrated to Peary Land on the northern route. The Thule Eskimos probably migrated across the J. P. Koch Fjord, the Wandeltal and the Jørgen-Brønlund Fjord .

Wulff's zoological and botanical collections completed the botanical exploration of Greenland. They were edited by Carl Hansen Ostenfeld, who in 1924 wrote the 48-page article The Vegetation of the North-Coast of Greenland Based Upon the Late Dr in the journal Meddelelser om Grønland. Th. Wulff's Collections and Observations published. The mushrooms were worked by Jens Lind (1874–1939), the lichens by Bernt Lynge (1884–1942).

Aftermath

Of Rasmussen's seven Thule expeditions, only the second claimed human lives. The tragic death of Wulff resulted in a police investigation, in which Koch refused to give evidence. Unlike Rasmussen, he wanted a negotiation in Copenhagen, not in Greenland. He also demanded the establishment of a court of honor. That did not happen, but two of the most important polar explorers, Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld and Fridtjof Nansen , consulted and declared, in agreement with Rasmussen and Freuchen, that Koch had behaved perfectly. Nevertheless, the relationship between Koch and Rasmussen remained permanently disrupted. In the opinion of the French polar explorer Jean Malaurie , Koch Rasmussen added that he had come into a situation where he had to decide whether to leave Wulff behind or to die with him.

After two smaller undertakings, Rasmussen started the scientifically important Fifth Thule Expedition in 1921. While an ethnographic research team was working in the Inuit settlement area on Hudson Bay , he himself drove with two polar skimos along the north coast of Canada to Alaska . For Lauge Koch, the second Thule expedition was the start of a series of geological expeditions to Greenland. He soon returned to North Greenland as leader of the Danish Jubilee Expedition 1920–1923. He spent a total of 6 winters and 33 summers here, about a third of his life.

literature

- Knud Rasmussen: In the home of the polar people. The second Thule expedition 1916–1918 . FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1922 ( digitized ).

- Knud Rasmussen: The Second Thule Expedition to Northern Greenland, 1916-1918 . In: Geographical Review . Volume 8, No. 2, 1919, pp. 116-125. doi: 10.2307 / 207633 .

- Knud Rasmussen, CH Ostenfeld, Morton P. Porsild, Lauge Koch: Scientific Results of the Second Thule Expedition to Northern Greenland, 1916–1918 . In: Geographical Review . Volume 8, No. 3, 1919, pp. 180-187. doi: 10.2307 / 207406 .

- Therkel Mathiassen: Knud Rasmussen's Sledge Expeditions and the Founding of the Thule Trading Station . In: Geografisk Tidsskrift . Volume 37, No. 1-2, 1934, pp. 16-29 (English).

- Knud Rasmussen: Report on the II. Thule-Expedition for the exploration of Greenland from Melville Bugt to De Long Fjord, 1916-1918 . In: Meddelelser om Grønland . Vol. 65, No. 14, 1927, pp. 1-180 (English).

Web links

- Film recordings of Thorild Wulff's Second Thule Expedition

Individual evidence

- ^ Knud Rasmussen: Report of the first Thule expedition 1912 . In: Meddelelser om Grønland . Volume 51, 1915, pp. 283-342, here p. 283 (English).

- ↑ Knud Rasmussen: In the home of the polar man. The second Thule expedition 1916–1918 , p. 2 .

- ↑ Knud Rasmussen: In the home of the polar man. The second Thule expedition 1916–1918 , p. 5 .

- ^ Knud Rasmussen: The Second Thule Expedition to Northern Greenland, 1916–1918 , p. 119 (English).

- ↑ Knud Rasmussen: In the home of the polar man. The second Thule expedition 1916–1918 , p. 4 .

- ↑ Knud Rasmussen: In the home of the polar man. The second Thule expedition 1916–1918 , p. 3 .

- ↑ Kalle Lekholm: Thorild Wulff . In: Vårt Göteborg on 2018-06-18, accessed April 17, 2020 (Swedish).

- ^ Peter Freuchen: Arctic Adventure. My Life in the Frozen North . Farrar & Rinehart, New York / Toronto 1935, p. 332 (English).

- ^ AK Higgins, Poul-Henrik Larsen, Jan C. Escher: På sporet af II. Thule ekspedition i Nordgrønland (PDF; 5.34 MB). In: Tidsskriftet Grønland . Volume 10, 1986, pp. 329-351 (Danish).

- ^ Knud Rasmussen, CH Ostenfeld, Morton P. Porsild, Lauge Koch: Scientific Results of the Second Thule Expedition to Northern Greenland, 1916–1918 , p. 186.

- ↑ Lauge Koch: Geological Observations . In: Knud Rasmussen: Greenland by the Polar Sea. The Story of the Thule Expedition from Melville Bay to Cape Morris Jessup . William Heinemann, London 1921, pp. 301-311, here pp. 305 f. (English)

- ^ Knud Rasmussen: The Routes of Eskimo Wanderings into Greenland . In: Knud Rasmussen: Greenland by the Polar Sea. The Story of the Thule Expedition from Melville Bay to Cape Morris Jessup . William Heinemann, London 1921, pp. 312–319 (English)

- ↑ Bjarne Grønnow, Jens Fog Jensen: The Northernmost Ruins of the Globe: Eigil Knuth's Archaeological Investigations in Peary Land and Adjacent Areas of High Arctic Greenland (= Meddelelser om Grønland , Man & Society , Volume 29). Danish Polar Center, Copenhagen 2003, ISBN 87-90369-65-3 ( oapen.org PDF; 10.1 MB)

- ↑ Jens Lind: Fungi collected on the north-coast of Greenland by the late Dr. Th. Wulff . In: Meddelelser om Grønland . Volume 64, 1924, pp. 289-304 (English).

- ↑ Bernt Lynge: Lichens collected on the north-coast of Greenland by the late Dr. Th. Wulff . In: Meddelelser om Grønland . Volume 64, 1923, pp. 281-288 (English).

- ^ Paul F. Hoffman: The Tooth of Time: Lauge Koch's Last Lecture . In: Geoscience Canada . Volume 40, 2013, pp. 242-255 (English).

- ↑ Jean Malaurie: Myth of the North Pole. 200 years of expedition history . National Geographic Germany, 2003, ISBN 3-936559-20-1 , p. 304

- ↑ Jean Malaurie: Myth of the North Pole. 200 years of expedition history . National Geographic Germany, 2003, ISBN 3-936559-20-1 , p. 306