Panic of 1907

The Panic of 1907, also known as the 1907 Bankers' Panic, was a financial crisis that occurred in the United States when the stock market fell close to 50% in January from its peak in the previous year. At the time, the economy was in a recession and there were numerous runs on banks and trust companies. The panic's primary cause was a retraction of liquidity by a number of banks in New York City that quickly spread across the nation, leading to the closures of both state and local banks and businesses. The 1907 panic was the fourth experienced in the United States in 34 years.

The crisis occurred after an attempt by Otto Heinze to corner the market in United Copper failed in October, 1906. When the bid failed, banks that had loaned money for the scheme experienced a number of runs which spread to affiliated banks and trusts, leading a week later to the downfall of the Knickerbocker Trust Company. With the collapse of New York's third largest trust company, fear spread throughout the city's trusts as regional banks pulled deposits from New York, and nationwide as people withdrew their deposits from regional banks.

At the time, the United States had no central bank to inject liquidity. The panic would have deepened further if not for the intervention of J.P. Morgan, who convinced other New York bankers to provide a backstop. By November the contagion had largely stopped, yet a small crisis emerged when it emerged that a large brokerage firm had borrowed heavily with the stock of Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TC&I) as collateral. Collapse of the firm's stock price was averted by an emergency takeover approved by anti-trust crusading president Theodore Roosevelt. The following year, Senator Nelson W. Aldrich established and chaired a commission to investigate the crisis and propose future solutions, leading to the creation of the Federal Reserve System.

Economic conditions

When U.S. President Andrew Jackson abolished the Second Bank of the United States, the U.S. was without a central bank, and the money supply in New York City fluctuated with the country's annual agricultural cycle. Each autumn money flowed out of the city as harvests were purchased and -- in an effort to attract money back -- interest rates were raised. Foreign investors then sent their money to New York to take advantage of the higher rates.[1] In January 1906, the Dow Jones Industrial Average hit a high of 103 and began a modest correction. The U.S. economy had been particularly unstable since the April 1906 earthquake which devastated San Francisco, prompting an even greater flood of money from New York to San Francisco to aid reconstruction. A further stress on the money supply occurred in late 1906, when the Bank of England raised its rates and more funds remained in London than expected.[2] From their peak in January, stock prices declined 18% by July 1906.

By late September, stocks had recovered about half of their losses. Between September 1906 and March 1907, the stock market slid, losing 7.7% of its capitalization[3] Then, from March 9 to March 26, stocks fell another 9.8%.[4] (This March collapse is sometimes referred to as a "rich man's panic"[5]) The economy remained volatile through the summer. A number of shocks hit the system: the stock of Union Pacific -- among the most common stocks used as collateral -- fell 50 points; that June an offering of New York City bonds failed; in July the copper market collapsed; in August the Standard Oil Company was faced with a $29 million fine for antitrust violations.[6] In the first nine months of 1907, stocks were off a total of 24.4%.[7]

On July 27, The Commercial & Financial Chronicle noted that "the market keeps unstable... no sooner are these signs of new life in evidence than something like a suggestion of a new outflow of gold to Paris sends a tremble all through the list, and the gain in values and hope is gone."[8] The fall season was always a vulnerable time for the banking system—combined with the roiled stock market, even a small shock could have grave repercussions.[9]

| Timeline of panic in New York City[10] | |

|---|---|

| Monday, Oct. 14 |

Otto Heinze begins purchasing to corner the stock of United Copper. |

| Wednesday, Oct. 16 |

Heinze's corner fails spectacularly. Heinze's brokerage house, Gross & Kleeberg is forced to close. This is the date traditionally cited as when the corner failed. |

| Thursday, Oct. 17 |

The Exchange suspends Otto Heinze and Company. The State Savings Bank of Butte, Montana, owned by Augustus Heinze announces it is insolvent. Augustus is forced to resign from Mercantile National Bank. Runs begin at Augustus' and his associate's Charles W. Morse's banks. |

| Sunday, Oct. 20 |

The New York Clearing House forces Augustus and Morse to resign from all their banking interests. |

| Monday, Oct. 21 |

Charles T. Barney is forced to resign from the Knickerbocker Trust Company because of his ties to Morse and Heinze. The National Bank of Commerce says it will no longer serve as clearing house. |

| Tuesday, Oct. 22 |

A bank run forces the Knickerbocker to suspend operations. |

| Wednesday, Oct. 23 |

J.P. Morgan persuades other trust company presidents to provide liquidity to the Trust Company of America, staving off its collapse. |

| Thursday, Oct. 24 |

Treasury Secretary George Cortelyou agrees to deposit Federal money in New York banks. Morgan persuades bank presidents to provide $23 million to the New York Stock Exchange to prevent an early closure. |

| Friday Oct. 25 |

Crisis is again narrowly averted at the Exchange. |

| Sunday, Oct. 27 |

The City of New York tells Morgan associate George Perkins that if they cannot raise $20–30 million by November 1, the city will be insolvent. |

| Tuesday, Oct. 29 |

Morgan purchased $30 million in city bonds, discreetly averting bankruptcy for the city. |

| Saturday, Nov. 2 |

Moore & Schley, a major brokerage, nears collapse because its loans were backed by the Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Company (TC&I), a stock whose value is uncertain. A proposal is made for U.S. Steel to purchase TC&I. |

| Sunday, Nov. 3 |

A plan is finalized for U.S. Steel to takeover TC&I. |

| Monday, Nov. 4 |

President Theodore Roosevelt approves U.S. Steel's takeover of TC&I, despite anticompetitive concerns. |

| Tuesday, Nov. 5 |

Markets are closed for Election Day. |

| Wednesday, Nov. 6 |

U.S. Steel completes takeover of TC&I. Markets begin to recover. Destabilizing runs at the trust companies do not begin again. |

Panic

Cornering copper

The 1907 panic began with a stock manipulation scheme to corner the market in F. Augustus Heinze's United Copper. Heinze had made a fortune as a copper magnate in Butte, Montana, and in 1906 moved to New York City, where he formed a close relationship with a notorious Wall Street banker Charles W. Morse. Morse had once successfully cornered New York City's ice market, and together with Heinze gained control of many banks—the pair served on at least six national banks, 10 state banks, five trust companies and four insurance firms.[11]

Augustus's brother, Otto, devised the scheme to corner United Copper, believing that the Heinze family already controlled a majority of the company. However, a significant number of the Heinze's shares had been borrowed, and Otto believed that many of these had been loaned to investors who hoped the stock price would drop, and they could thus replace the shares cheaply, pocketing the difference in a technique known as short selling. Otto proposed a scheme called a "bear squeeze", whereby the Heinzes would aggressively purchase as many remaining shares as possible, and then force the short sellers to pay for their borrowed shares. The aggressive purchasing would drive up the prices, he believed and, unable to find shares elsewhere, the short sellers would have no option but to turn to the Heinzes, who could then name their price.[12]

To finance the scheme, Otto, Augustus and Charles Morse met with Charles T. Barney, president of the city's third largest trust, the Knickerbocker Trust Company. Barney had provided financing for previous Morse schemes. Morse, however, cautioned Otto that he needed much more money than he had to attempt the squeeze and Barney declined to provide funding.[13] Otto decided to attempt the corner anyway. On Monday, October 14 he began aggressively purchasing shares of United Copper, which rose in one day to $52 per share from $39 per share. On Tuesday, he issued the call for short-sellers to give back the borrowed stock. Share prices rose to nearly $60, but the short-sellers were able to find plenty of United Copper shares from sources other than the Heinzes. Otto had misread the market, and the share price of United Copper began to collapse.[14]

The stock closed at $30 on Tuesday and fell to $10 by Wednesday. Otto Heinze was ruined. The stock of United Copper was traded outside the hall of the New York Stock Exchange literally "on the curb" (this curb market would later become the American Stock Exchange). After the crash, The Wall Street Journal reported, "Never has there been such wild scenes on the Curb, so say the oldest veterans of the outside market."[15]

Contagion spreads

The failure of the attempt at a corner left Otto unable to meet his obligations and drove his brokerage house, Gross & Kleeberg, into bankruptcy. On Thursday October 17, the New York Stock Exchange suspended Otto's trading privileges. As a result the State Savings Bank of Butte Montana (owned by F. Augustus Heinze) announced its insolvency. The bank had held United Copper stock as collateral for some of its lending and had been a correspondent bank for the Mercantile National Bank in New York City; of which F. Augustus Heinze was then president.

F. Augustus Heinze's affiliation with the corner and the insolvent State Savings Bank was too much for the board of the Mercantile. Although they forced him to resign before that lunch time,[16] by then it was too late. As news spread of the collapse, depositors rushed en masse to withdraw money from the Mercantile National Bank. The Mercantile had enough capital to withstand a few days withdrawals, but when depositors began to pull cash from the banks of the Heinzes' associate Charles W. Morse, runs occurred at both the Morse's National Bank of North America and the New Amsterdam National. Afraid of the impact the tainted reputations of Augustus Heinze and Morse could have on the banking system, the New York Clearing House (a consortium of the city's banks) forced Morse and Heinze to resign all banking interests.[17] By the weekend after the failed corner, there was not yet systemic panic. Funds were withdrawn from Heinze-associated banks, only to be deposited with other banks in the city.[18]

Panic strikes the trusts

At the time, trust companies were booming; in the decade before 1907, their assets had grown by 244 percent. During the same period, national bank assets grew by 97 percent, while state banks in New York grew by 82 percent.[19] The leaders of the high-flying trusts were mainly prominent members of New York's financial and social circles. One of the most respected was Charles T. Barney, whose father-in-law William Collins Whitney was a famous financier, while his Knickerbocker Trust Company was the third largest such fund in New York.[20]

Because of past association with Charles W. Morse and F. Augustus Heinze, on Monday Oct. 21, the board of the Knickerbocker asked that Barney resign (depositors may have first begun to pull deposits from the Knickerbocker on October 18, prompting the concern[21]). That day, the National Bank of Commerce announced it would not serve as clearing house for the Knickerbocker. On October 22, the Knickerbocker faced a classic bank run. From the bank's opening, the crowd grew. As The New York Times reported, "as fast as a depositor went out of the place ten people and more came asking for their money [and the police] were asked to send some men to keep order."[22] In less than three hours, $8 million was withdrawn from the Knickerbocker. Shortly after noon it was forced to suspend operations.[23]

As news spread, other banks and trust companies were reluctant to lend out any money. The interest rates on loans to brokers at the stock exchange soared and, with brokers unable to get money, stock prices fell to a seven year low not seen since December of 1900.[24] The panic quickly spread to two other large trusts, Trust Company of America and Lincoln Trust Company. By Thursday, October 24, a chain of failures littered the street: Twelfth Ward Bank, Empire City Savings Bank, Hamilton Bank of New York, First National Bank of Brooklyn, International Trust Company of New York, Williamsburg Trust Company of Brooklyn, Borough Bank of Brooklyn, Jenkins Trust Company of Brooklyn and the Union Trust Company of Providence.[25]

Enter J.P. Morgan

When the chaos began to shake the confidence of New York's banks, the city's most famous banker was out of town. J.P. Morgan, president of the eponymous J.P. Morgan & Co., was attending a church convention in Richmond, Virginia. Morgan was not only by far the city's wealthiest and most-connected banker, but had experience with crisis from when he helped rescue the U.S. Treasury itself during the Panic of 1893. As news of the crisis gathered, Morgan returned to Wall Street from his convention late on the night of Saturday October 19. The following morning, the library of Morgan's brownstone at Madison Avenue and 36th St. had become a revolving door of New York City bank and trust company presidents arriving to share information about (and seek help surviving) the impending crisis.[26][27]

Morgan and his associates had examined the books of the Knickerbocker Trust, but decided it was insolvent and did not intervene to stop the run. Its failure triggered runs on even healthy trusts, prompting Morgan to take charge of the rescue operation. On the afternoon of Tuesday, October 22, the president of the Trust Company of America asked Morgan for assistance. That evening Morgan conferred with George F. Baker, the president of First National Bank, James Stillman of the National City Bank of New York (the ancestor of Citibank), and the United States Secretary of the Treasury, George B. Cortelyou. Cortelyou said that he was ready to deposit government money in the banks to help shore up their deposits. After an overnight audit of the Trust Company of America’s books showed the institution to be sound, on Wednesday afternoon Morgan declared, “This is the place to stop the trouble, then."[28]

As a run began on the Trust Company of America, Morgan worked with Stillman and Baker to liquidate the Trust's assets to allow the bank to pay depositors. The bank survived to the close of business, but Morgan knew that additional money would be needed to keep it solvent through the following day. That night he assembled the presidents of the other Trust Companies and held them in a meeting until they agreed to provide loans of $8.25 million to allow the Trust Company to stay open the next day.[29] The meeting ran until midnight, but on the Thursday morning Cortelyou deposited around $25 million into a number of New York banks.[30] John D. Rockefeller, the wealthiest man in America, deposited a further $10 million in Stillman's National City Bank.[31] Rockefeller's massive deposit left the National City Bank with the deepest reserves of any bank in the city. To instill public confidence, Rockefeller phoned Melville Stone, the manager of the Associated Press, and told him that he would pledge half of his wealth to maintain America's credit.[32]

Stock exchange nears collapse

Despite the infusion of cash, the banks of New York were reluctant to make the short-term loans they typically provided to facilitate daily stock trades. Unable to obtain these funds, prices on the exchange began to crash. At 1:30 p.m. Thursday October 24, Ransom Thomas, the president of the New York Stock Exchange, rushed to Morgan's offices to tell him that he would have to close the exchange early. Morgan was emphatic that an early close of the exchange would be catastrophic.[33][34]

Morgan summoned the presidents of the city's banks to his office. They started to arrive at 2 p.m.; Morgan informed them that as many as 50 stock exchange houses would fail unless $25 million was raised in 10 minutes. By 2:16 p.m., 14 bank presidents had pledged $23.6 million to keep the stock exchange afloat. The money reached the market at 2:30 p.m., in time to finish the day's trading, and by the 3 o'clock close $19 million had been loaned out. Disaster was averted. Morgan eschewed the press, but as he left his offices that night he made a statement to reporters: "If people will keep their money in the banks, everything will be all right."[35]

Friday, however, saw more panic on the exchange. Morgan again approached the bank presidents, but this time was only able to convince them to pledge $9.7 million. In order for this money to keep the exchange open, Morgan decided the money could not be used for margin sales. The volume of trading on Friday was 2/3 that of Thursday. The markets again narrowly made it to the closing bell.[36]

Crisis of confidence

|

|

|

|

| (Clockwise from top left) John D. Rockefeller, George B. Cortelyou, Lord Rothschild, and James Stillman. Some of the best known names on Wall Street issued positive statements to help restore confidence in the economy. | |

Morgan, Stillman, Baker and the other city bankers were unable to pool money indefinitely, while even the U.S. Treasury was low on funds. Public confidence needed to be restored, and on Friday evening the bankers formed two committees—one to persuade the clergy to calm their congregations on the Sunday, and second to explain to the press the various aspects of the financial rescue package. However, when Europe's most famous banker, Lord Rothschild, sent word of his "admiration and respect" for Morgan, his remark was represented by newspapers as just an idle boost.[37] In an attempt to gather confidence, the Treasury Secretary Cortelyou agreed that if he returned to Washington it would send a signal to Wall Street that the worst had passed.[38][39]

To ensure a free flow of funds on Monday, the New York Clearinghouse issued $100 million in loan certificates to be traded between banks to settle balances, allowing them to retain cash reserves for depositors.[40] Reassured both by the pastor and the newspapers, and with their balance sheets flushed with cash, a sense of order returned to New York that Monday.[41]

Unbeknown to the city, a new crisis was being averted in the background. On the Sunday, Morgan's associate, George Perkins, became aware that the City of New York required at least $20 million by November 1 unless it was to become bankrupt. The city tried to source money through a standard bond issue, but failed to gather enough finance in a then tight climate. On the Monday and again on the Tuesday, the New York Mayor George McClellan approached Morgan for assistance. In an effort to avoid the disastrous signal that a New York City bankruptcy would send, Morgan wrote a contract to purchase $30 million of city bonds.[42][43]

Resolution

Although calm was restored in New York by Saturday, November 2, a further crisis loomed. One of the exchange's largest brokerage firms, Moore & Schley, was heavily in debt and in danger of collapse. The firm had borrowed extensively, using stock from the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TC&I) as collateral. The troubles meant there was little demand on the market for TC&I, and not only would Moore & Schley be unable to repay their creditors if the loans were called in, but the market would be flooded with TC&I stock. Thus it was presumed bank failures would spread rapidly.[44]

The danger remained that if the following morning's exchange opened with Moore & Schley's fate still uncertain, fear would result in a massive crash. One obstacle remained: the anti-trust crusading President Theodore Roosevelt.[45] Morgan retained one ally that had not been tapped, the U.S. Steel Corporation, which he had helped form through the merger of the steel companies of Andrew Carnegie and Elbert Gary. U.S. Steel had no involvement in banking, but could acquire TC&I.[46] Morgan, Perkins, Baker, and Stillman, as well as U.S. Steel's Gary and Henry Clay Frick worked Saturday and Sunday arranging the terms and by Sunday night had a plan for acquisition.

Frick and Gary traveled on a midnight train to the White House to implore Roosevelt to allow, before 10 a.m., a company with a 60 percent market share—already the antithesis of his trust-busting efforts under the Sherman Antitrust Act—to make a massive acquisition. Roosevelt's personal secretary refused to see them, yet Frick and Gary convinced James Rudolph Garfield, the Secretary of the Interior, to bypass the secretary and allow them go directly to the president. With less than an hour before markets opened, Roosevelt and Secretary of State Elihu Root, began to review the proposed takeover and absorb the news of a potential crash if the merger was not approved.[47][48]

Roosevelt relented, and he later said of the meeting, "It was necessary for me to decide on the instant before the Stock Exchange opened, for the situation in New York was such that any hour might be vital. I do not believe that anyone could justly criticize me for saying that I would not feel like objecting to the purchase under those circumstances."[49] When news reached New York, confidence soared. The Commercial & Financial Chronicle reported that "the relief furnished by this transaction was instant and far-reaching."[50] The final crisis of the panic had been averted.[51]

Aftermath

The panic of 1907 arose during a lengthy economic contraction, measured by the National Bureau of Economic Research as beginning in May 1907 and lasting until June 1908.[52] Bruner & Carr 2007 cite a number of statistics quantifying the damage caused during the crisis and resulting recession. Industrial production dropped further than after any bank run to that date, and that year saw as a direct result the second highest volume of bankruptcies yet. Production fell by 11 percent, imports by 26 percent while unemployment rose to 8 percent from under 3 percent. Immigration dropped to 750,000 people in 1909 from 1.2 million people two years earlier.[53]

The realization of both the severity of the crisis and of the outsized role of J.P. Morgan gave renewed impetus to national discussion on banking reform.[54] In May 1908, Congress passed the Aldrich–Vreeland Act which established the National Monetary Commission to investigate the panic and to propose legislation to regulate banking.[55] Senator Nelson Aldrich (R–RI), the chairman of the National Monetary Commission, went to Europe for almost two years to study that continent's banking systems.

Central bank

A significant difference between European and the U.S. banking system was the apsence of a central bank in the United States. Through their central banks, European countries were able to extend the supply of money during periods cash reserves were low. The idea that the United States economy was made vulnerable without a central bank was not new. Early in 1907, Jacob Schiff of Kuhn, Loeb & Co. warned in a speech to the New York Chamber of Commerce that "unless we have a central bank with adequate control of credit resources, this country is going to undergo the most severe and far reaching money panic in its history."

Aldrich convened a secret conference with a number of the nation's leading financiers at the Jekyll Island Club, off the coast of Georgia, to discuss monetary policy and the banking system. In November 1910, Aldrich and A.P. Andrews (Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Department), Paul Warburg (a naturalized German representing Kuhn, Loeb & Co.), Frank A. Vanderlip (president of the National City Bank of New York), Henry P. Davison (senior partner of J. P. Morgan Company), Charles D. Norton (president of the Morgan-dominated First National Bank of New York), and Benjamin Strong (representing J. P. Morgan), produced a design for a "National Reserve Bank".[56]

Forbes magazine founder B. C. Forbes wrote several years later:

Picture a party of the nation’s greatest bankers stealing out of New York on a private railroad car under cover of darkness, stealthily riding hundreds of miles South, embarking on a mysterious launch, sneaking onto an island deserted by all but a few servants, living there a full week under such rigid secrecy that the names of not one of them was once mentioned, lest the servants learn the identity and disclose to the world this strangest, most secret expedition in the history of American finance. I am not romancing; I am giving to the world, for the first time, the real story of how the famous Aldrich currency report, the foundation of our new currency system, was written.[57]

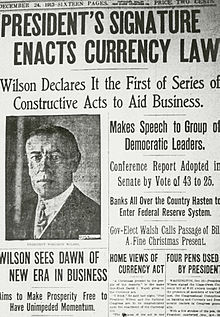

The final report of the National Monetary Commission was published on January 11, 1911. For nearly two years legislators debated the proposal and it was not until December 22, 1913, that Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act. President Woodrow Wilson signed the legislation immediately. The legislation was enacted on December 22, 1913, creating the Federal Reserve System.[58] Charles Hamlin became the Fed's first chairman, and none other than Morgan's deputy Benjamin Strong became president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the most important regional bank with a permanent seat on the Federal Open Market Committee.[58]

Pujo Committee

Although Morgan was briefly seen as a hero, wide fears concerning plutocracy and concentrated wealth soon eroded this perception. Not only had Morgan's bank survived but the Trust Companies that were a growing rival to traditional banks were badly damaged. Some anlysists believed that the panic had been engineered, either to punish Heinze's or as part of an elaborate plot for U.S. Steel to acquire TC&I. Although Morgan lost $21 million in the panic, and the significance of the role he played in staving worse disaster is not disputed, he became the focus of intense scrutiny and criticism.[59]

The chair of the House Committee on Banking and Currency, Representative Arsène Pujo, (D–La. 7th) convened a special committee to investigate a "money trust", the de facto monopoly of Morgan and New York's other most powerful bankers. The committee issues a scathing report of the banking community: finding that the officers of J.P. Morgan & Co. were on the boards of directors of 112 corporations with a market capitalization of $22.5 billion (with the total capitalization of the NYSE then estimated at $26.5 billion).[60]

Despite his ill health, J.P. Morgan testified before the Pujo Committee, facing several grueling days of questioning from Samuel Untermyer. Untermyer and Morgan's famous exchange about the fundamentally psychological nature of banking—that it is an industry built on trust—is oft quoted to this day:[61]

Untermyer: Is not commercial credit based primarily upon money or property?

Morgan: No, sir. The first thing is character.

Untermyer: Before money or property?

Morgan: Before money or anything else. Money cannot buy it… a man I do not trust could not get money from me on all the bonds in Christendom.[61]

Associates of Morgan blamed his continued physical decline on the hearings. In February he became very ill and on March 31, 1913—nine months before the "money trust" would be officially replaced as lender of last resort by the Federal Reserve—J.P. Morgan died.[61]

References

- ^ Tallman & Moen 1990, p. 3–4

- ^ Tallman & Moen 1990, p. 4

- ^ as measured by an index of all listed stocks, according to Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 19

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 20

- ^ Kindleberger 2005, p. 102

- ^ Kindleberger 2005, p. 102

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 32

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 31

- ^ Tallman & Moen 1990, p. 4

- ^ Distilled from Bruner & Carr 2007

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 38–40

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 43–44

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 45

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 47–48

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 49

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 51–55

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 61–62

- ^ Tallman & Moen 1990, p. 7

- ^ Moen & Tallman 1992, p. 612

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 68

- ^ Tallman & Moen 1990, p. 7

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 79

- ^ Tallman & Moen 1990, p. 7

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 85

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 101

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 83–86

- ^ Chernow 1990, p. 123

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 87–88

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 93

- ^ Tallman & Moen 1990, p. 8

- ^ Tallman & Moen 1990, p. 8

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 542–44

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 99

- ^ Chernow 1990, p. 125

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 100–01

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 102–03

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 103–07

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 108

- ^ Chernow 1990, p. 126

- ^ Tallman & Moen 1990, p. 9

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 111

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 111–12

- ^ Chernow 1990, p. 126

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 116

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 131

- ^ Tallman & Moen 1990, p. 8–9

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 132

- ^ Chernow 1990, p. 128–29

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 132

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 133

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 132–33

- ^ US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions, National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved on September 22, 2008.

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 141–42

- ^ Smith 2004, p. 99–100

- ^ Miron 1986, p. 130

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 143

- ^ Griffin 1998

- ^ a b Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 146

- ^ Strouse, Jean. "Here's How It's Done, Hank: A Parable From a Crisis of a Century Ago." The Washington Post (September 28, 2008), p. b1. Retrieved on September 30, 2008.

- ^ Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 148

- ^ a b c Bruner & Carr 2007, p. 182–83

Bibliography

- Bruner, Robert F.; Carr, Sean D. (2007), The Panic of 1907; Lessons Learned from the Market's Perfect Storm, Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0470152638

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - Calomiris, Charles W.; Gorton, Gary (1992), "The Origins of Banking Panics: Models, Facts and Bank regulation", in Hubbard, R. Glenn (ed.) (ed.), Financial Markets and Financial Crises, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

{{citation}}:|editor-first=has generic name (help) - Caporale, Tony; McKiernan, Barbara (1998), "Interest Rate Uncertainty and the Founding of the Federal Reserve", The Journal of Economic History, 58 (4): 1110–17 JSTOR: 2566853 (subscription required). Retrieved on September 17, 2008.

- Carosso, Vincent P. (1987), The Morgans: Private International Bankers, 1854-1913, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0674587294

- Chernow, Ron (1990), The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance, New York: Grove Press, ISBN 0802138292

- Chernow, Ron (1998), Titan : the life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., New York: Random House, ISBN 0679438084

- Fettig, David (ed) (1989), "F. Augustus Heinze and the Panic of 1907", The Region, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

{{citation}}:|first=has generic name (help). Retrieved on September 14, 2008 - Friedman, Milton (1963), A Monetary History of the United States: 1867-1960, Princeton: Princeton University Press

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Gorton, Gary, "Clearinghouses and the Origin of Central Banking in the United States", The Journal of Economic History, 45 (2): 277–283 JSTOR: 2121695 (subcription required). Retrieved on September 17, 2008.

- Gorton, Gary; Huang, Lixin (2006), "Bank panics and the endogeneity of central banking", Journal of Monetary Economics, 53 (7): 1613–1629, doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2005.05.015

- Griffin, G. Edward (1998), The Creature from Jekyll Island : A Second Look at the Federal Reserve, American Media, ISBN 0-912986-21-2

- Kindleberger, Charles P.; Aliber, Robert (2005), Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises (5th ed.), Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0471467144

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - Miron, Jeffrey A. (1986), "Financial Panics, the Seasonality of the Nominal Interest Rate, and the Founding of the Fed" (PDF), American Economic Review, 76 (1): 125–40

- Moen, Jon; Tallman, Ellis (1992), "The Bank Panic of 1907: The Role of the Trust Companies", The Journal of Economic History, 52 (3): 611–30. JSTOR: 2122887 (subcription required). Retrieved on September 17, 2008.

- Odell, Kerry A.; Weidenmier, Marc D. (2004), "Real Shock, Monetary Aftershock: The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and the Panic of 1907", The Journal of Economic History, 64 (4): 1002–1027, doi:10.1017/S0022050704043062

- Smith, B. Mark (2004), A History of the Global Stock Market; From Ancient Rome to Silicon Valley (2004 ed.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0226764044

- Sprague, Oliver M.W. (1908), "The American Crisis of 1907", The Economic Journal, 18: 353–72, doi:10.2307/2221551

- Tallman, Ellis W.; Moen, Jon (1990), "Lessons from the Panic of 1907" (PDF), Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Economic Review, 75: 2–13. Retrieved on September 14, 2008

External links

- Panic of 1907 on National Public Radio

- Account of the Panic by "The Daily Reckoning"

- Boston Federal Reserve Board account of the Panic

- Moen, Jon. Panic of 1907 EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. August 15, 2001.