Ancient Egyptian judgment of the dead

The ancient Egyptian judgment of the dead (also " court of the underworld ") is a concept in the mythology of ancient Egypt . It consists of a tribunal of 42 judges of the dead who decide in the Amduat , Book of Gates and Book of the Dead which Ba souls are allowed to enter the underworld (Amduat) or which Ba souls are allowed to unite with their corpses (Book of Gates, Book of the Dead) .

The primary goal of a successful trial before the judgment of the dead was the transformation of the dead into a justified ancestral spirit and not, as is often assumed, the transition from the world of the living to the world of the dead. The physical purity of the dead was essential for this. The positive decision of the judgment of the dead documented the successful detachment of sins from the body of the dead. With the subsequent transfiguration it was possible for the dead to transfer to Sechet-iaru (“fields of rushes”) into the world of gods and to continue to exist with the gods.

historical development

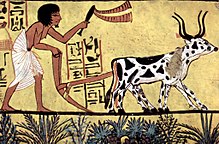

The idea of a judgment of the dead already emerged in the Old Kingdom and is attested in the pyramid texts in connection with the royal ascent into heaven . Before the royal ascension began, the ritual of embalming and mummification had to be performed. The associated removal of body fluids with accompanying transfiguration took place by additional dousing of the body with water, which was then placed on a structure similar to a water basin. The ancient Egyptians described this process as "crossing the lake". The divine judgment of the dead, which at that time could only be invoked by the king ( Pharaoh ), posed a danger, since a "request to review the deeds" resulted in a negative judgment in the event of the king's misconduct, which not only prevented the ascension into heaven, but also resulted in an eternal stay led in the "hidden realm of death". The idea of the judgment of the dead was thus initially limited to the king himself and his closest confidants.

Only in the course of the Middle Kingdom did the new theological concept of the third level ( Duat ) reunite with the body of the Ba soul, which appears mainly in the form of a bird, also in the private sphere after successful examination by the judgment of the dead, as the bearer of the immortal forces in the hereafter Dead, which was therefore to be preserved as a mummy. The idea of the afterlife was influenced by the world the Egyptians saw: a life-giving river, forming a wide, fertile delta in the north, surrounded by deserts in the west and east, places of death (the west, place of the setting sun, was synonymous for the realm of the dead). The soul initially had to endure a delicate journey through the underworld, constantly threatened by demons and other dangers, a concept that is widespread in many other religions, including Hinduism and Buddhism .

The judgment of the dead (also called “ Hall of Complete Truth ”), which was modified in the New Kingdom and before which every non-royal deceased had to appear, received canonical regulations and precise framework conditions for the first time . Whereas in the past the deceased could be charged with any offense during the judge of the dead, every ancient Egyptian now knew in advance what “charges” awaited him. Due to canonization, life before death could be adapted to the laws of the judgment of the dead. The judgment of the dead consisted of a tribunal headed by Osiris , an old chthonic god, of 42 judges of the dead (Gaugötter), who were also demonic and who decided which Ba souls were allowed to enter the afterlife . The basic idea was that every dead person in the hereafter would be freed from the "sins of life" before the judgment of the dead. In the event of failure, the deceased was threatened with staying in the keku-semau (darkness), which could not be reached by the life-giving rays of the night sun. In this respect, the judgment of the dead served as permission to receive the necessary transfiguration . The possession of the book of the dead already represented a magical protection against the endangerment of the judgment of the dead in order to pass the 82 negative confessions of guilt according to chapter 125 of the book of the dead . There, in two lists, all things are named, of which the dead must be acquitted in order to be able to make a successful reunion between the Ba soul and his corpse. Failure would result in a "second and final death". The " Book of the Temple ", which also contains similar negative confessions of guilt for priests, served as a direct forerunner of verse 125 . Joachim Friedrich Quack dates those priestly confessions to the Middle Kingdom.

According to Book of the Dead 125, the dead entered the court under the guidance of the jackal-headed god Anubis . The goddess Maat , symbolized as a feather, played a decisive role in the actual test and was actually an old, later personified symbol of harmony and justice. In the shape of a feather, when the heart of the dead was weighed, it formed the counterweight on the scales of justice in the funeral scene. In addition, her husband, the ibis-headed Thoth , lord of knowledge, writing and calculating as well as the patron god of officials, acted as the god of the dead and helper of the presiding Osiris as the recorder of the proceedings during the judgment of the dead. If heart and mate were in balance, the deceased had passed the test and was brought before the throne of Osiris by Horus , son of Osiris and patron god of Pharaoh, to receive his judgment there; but if the judgment was negative, after the Amarna period the heart was given up to the goddess Ammit for destruction. The correspondence of heart and mate did not automatically prove a correct lifestyle, but the ability of the deceased to allow himself to be "ritually cleansed of his evil deeds". It was not “innocence” that determined the judgment, but the ability to detach oneself from one's sins . The subjects of shamanism , prophetism and mysticism were unknown in connection with the judgment of the dead before the Greco-Roman times in ancient Egypt.

The judgment of the dead in relation to the king (Pharaoh)

Since the early dynastic period the king (Pharaoh) saw himself as the son of the heavenly deities; he was at the same time their agent, envoy, partner and successor. The latter equation refers to the reign of the gods who, according to ancient Egyptian mythology, previously ruled the earth . In the meantime, Egyptology rejected the concept that was held well beyond the middle of the 20th century, which equated the king with a deity, and based on the sources, redefined the role of the king in accordance with ancient Egyptian mythology. The special role identified the king as a “divine mediator”, who passed on the plans of the heavenly gods to the people and made sure that the “divine will” was implemented accordingly. After the death of the king (Pharaoh), he began his ascent into the heavens in order to be able to exercise his office there as a deified king "born again in association with other deities and ancestors ". The “ ritually activated divinity” with regard to the office of king at the coronation put the king in the role of the earthly representative of the gods. Associated with the deities handed over "their thrones, long years of rule, and the land of Egypt," so that the king with divine blessing the world order Maat maintains and protects against foreign conquerors. From the second millennium BC A text is known that was installed in numerous temples and describes the divine legitimation:

“Re instituted the King on the earth of the living forever and ever. [So he works] in judging people, in satisfying the gods, in letting the truth arise and in the annihilation of sin. He gives food to the gods, sacrifices to the transfigured. "

In all royal graves since the New Kingdom the vignette of the Book of the Dead verse 125, which illustrates the swaying of the heart , is missing . Associated with this, there are no images of Ammit as a “demonic corpse eater”. The reasons can be seen in the self-image of the king (Pharaoh), who carries and symbolizes the principle of mate . Therefore, the kings in their graves adapted the content of the texts to the Maat principle, in particular to the effect that the king did not have to make a “negative confession of guilt”. In contrast to the Book of the Dead 125, in the depictions of the royal tombs, the king's justification sequence was omitted . The judges of the dead generally acquitted him of personal misconduct on the basis of the Maat principle. Ammit is therefore shown in the royal tombs exclusively as a human goddess and thus functioned as the patron goddess of the deceased king. In one out of the grave of Tutankhamun originating inscription on a hippo -Bahre states: "The king is loved by her." The king (Pharaoh) saw himself as a personified Osiris and therefore did not have to answer before the judgment of the dead or appear before Osiris as a deceased. The correspondingly changed king inserts explain the self-image:

"The king sits down on the body of the groove [...] The king goes out and stops at the gateway to the west [...] The king walks through the gates to Re [...] He walks behind Re."

The judgment of the dead in relation to non-royal persons

After death, according to the ideas of the Egyptians, the Ba soul united in the duat with the body of the deceased. The concept of the afterlife was influenced by the world the Egyptians saw in life: a sandy-banked river flowing through a plain surrounded by mountains. For the newly arrived soul , there were terrifying obstacles such as dangerous lakes, islands and deserts, a lake of fire and a hill on which a head appeared when the soul approached it. There were also demons with names such as: "The backward looking man who comes out of the abyss". The demons tried to catch the soul with sticks, spears, bird traps and nets. The soul could only save itself if it knew the secret names of the demons that could be read in the Book of the Dead.

Egyptian coffin texts could therefore contain maps of the underworld and magic spells to help the dead in the realm of the dead to cope with the dangers. Such a coffin text also describes the fate of exposed enemies of the sun god Re : They were beheaded, dismembered, burned or thrown alive into a kettle of boiling water in the extermination site .

The judgment of the dead in relation to ancient Egyptian astronomy

Both the deceased and the invisible Chatiu demons have to make the “negative confession of guilt” in front of the 42 adjunct judges of the Book of the Dead . This made the "solution" one of the funeral rites . The “negative admission of guilt” of the Chatiu demon is probably based on the necessary purity of the priest in charge, who was only able to perform the recitations in this way. In addition, priestly purity was a prerequisite for entering the temple. After the end of the service of a Phylene priest , a new purification was necessary before taking office. The priest's confession of purity as an access authorization is therefore probably directly related to the “decade solution”.

In the Book of the Dead, the solution is standardized under no. 158 in the “Saying for a golden collar ”: “Loosen me, look at me. I am one of those (Chatiu deans) who belong to the solution when they see Geb. ”Book of the dead entry 125 also points in the same direction:“ Relieve a man from sins. To see the face of the gods. ”In this regard, it is written on an ostraka :“ May you remove the corruption and show gentleness, one does what you have said. ”The desired“ solution ”is therefore the request of the deceased, how a temporarily dead dean to be reborn at the end of the 70 day funeral rites. In the book of breathing it is reported that the deceased was brought to a lake before being wrapped in mummy bandages to “relieve his evils” in order to perform the magical rites there.

literature

- Jan Assmann : Farewell to the dead: mourning rituals in a cultural comparison . Wallstein, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-89244-951-5 .

- Jan Assmann: Death and the afterlife in ancient Egypt. Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-49707-1 .

- Hans Bonnet : Article afterlife judgment. In: Hans Bonnet: Reallexikon der Ägyptischen Religionsgeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin 1952, pp. 334-341.

- Wolfgang Helck / Eberhard Otto : afterlife court. In: Small Lexicon of Egyptology. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-447-04027-0 , p. 134 f.

- Klaus Koch: History of the Egyptian Religion. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-17-009808-X .

- Siegfried Morenz : Right and Left in the Judgment of the Dead. In: Siegfried Morenz: Religion and History of Ancient Egypt. Collected Essays. Böhlau, Cologne / Vienna 1975, pp. 281–294.

- Richard H. Wilkinson : The world of the gods in ancient Egypt. Belief, power, mythology. Theiss, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-8062-1819-6 , p. 84.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Farewell to the dead: mourning rituals in a cultural comparison . Göttingen 2007, p. 320.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Death and Beyond in Ancient Egypt . Munich 2001, p. 42.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Ma'at. Justice and Immortality in Ancient Egypt. Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39039-0 , pp. 122-159.

- ↑ Susanne Bickel: The combination of worldview and state image. Aspects of Politics and Religion in Egypt. In: Reinhard Gregor Kratz, Hermann Spieckermann: Images of Gods, Images of God, Images of the World: Polytheism and Monotheism in the World of Antiquity. (= Research on the Old Testament. 2nd row, nos. 17-18). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2006, ISBN 3-16-148673-0 , pp. 82-84 and 87-88.

- ↑ Christine Seeber: Investigations into the representation of the judgment of the dead in ancient Egypt . In: Münchner Ägyptologische Studien (MÄS), No. 35 . Munich 1976, pp. 127-128.

- ↑ Friedrich Abitz: Pharao as God in the underworld books of the New Kingdom (= Orbis biblicus et orientalis. Vol. 146). University Press, Freiburg (CH); Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen (both) 1995, ISBN 978-3-7278-1040-4 , p. 193.

- ↑ Horst Beinlich, Mohamed Saleh: Corpus of the hieroglyphic inscriptions from the tomb of Tutankhamun: With concordance of the numbering systems of the "Journal d'entrée" of the Egyptian Museum Cairo, the handlist to Howard Carter's Catalog of objects in Tutankhamūns tomb and the exhibition number of the Cairo Egyptian Museum . Griffith Institute, Oxford 1989, ISBN 0-900416-53-X , p. 137.

- ↑ Edda Bresciani and a .: La tomba di Ciennehebu, capo del flotta del Re. Giardini, Pisa 1977, p. 83.