Antonius Margaritha

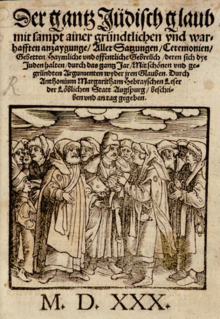

Antonius or Anthonius or Anton Margaritha (* around 1492 in Nuremberg , † in the spring of 1542 in Vienna ) was a Jewish convert whose work Der gantz Judisch Glaub represents a kind of “revelatory literature” with anti-Jewish objectives. It was used as a source for early modern anti-Jewish writings . Despite its polemical character, the whole is Jewish faithbut also a source for the everyday life of Jews in the early 16th century and is evaluated by historians in this sense. Margaritha's book contains the first translation of a Jewish prayer book into German.

Life

Family background

Anthonius Margaritha came from a rabbi family. His grandfather Jakob Margoles (Margolith) was the last chief rabbi of Nuremberg before the expulsion of the Jews from the city in 1499. He had previously worked as a rabbi in several southern German cities and was considered an expert on divorce law. As a rabbi, Jakob Margoles was also the contact person for contacts between Christians and the Jewish community. Johannes Reuchlin asked him if he could get him some Kabbalistic texts, but Margoles replied that they were not available in Nuremberg. After being expelled from Nuremberg, he became a rabbi in Regensburg , an office he held until his death in 1501. He was married twice and had three sons Isaac (d. 1525), Samuel (d. 1551) and Shalom Shachna (d. 1573), where Isaac and Samuel were probably children from their first marriage and the much younger Shalom Shachna a son from Jacob second marriage. While Samuel was succeeding his father as rabbi of Regensburg, the other two brothers moved to Prague , where, among other things , they dealt with the publication of the work on divorce law that their father had written.

Samuel Margaritha married Saidia Straubinger. His wife was a member of the long-established and wealthy Straubinger-Veiflin family in Regensburg. The couple lived in Nuremberg until 1499, and their son Anthonius was born there. His Jewish name is not known, but the consonants of his baptismal name Anthonius, N-Th-N, suggest the Hebrew names Nathan or Jonathan. Two brothers named Baruch and Moses Mordechai are known; Baruch served as Chasan in Regensburg and later in Italy, and Moses Mordechai became a rabbi in Cracow .

regensburg

Anthonius Margaritha's conversion was preceded by experiences he had made as a Jewish child and youth in Regensburg. This community was in economic decline in the 15th century and had lower tax revenues, which made its security situation increasingly precarious. The Regensburg city council issued anti-Jewish regulations, e.g. B. 1462 a prohibition for Christian midwives to assist a Jewish woman with childbirth. There were two ritual murder charges in the 1470s. A wandering Jew was arrested in Trento on charges of murdering a Christian child ( Simon von Trient ). He was baptized and accused several Regensburg Jews of having committed ritual murder a few years ago . Among them was Rabbi Eisik Stein, a relative of Saidia Straubinger. These people were arrested but eventually released for a large sum of money. In 1499 the Regensburg Jewish community complained to Duke Georg von Bayern-Landshut that Christian bakers refused to sell them bread and that their children were in need. Georg caused the city council to stop this behavior by the bakers. The sources are largely silent on how the Jewish minority reacted to all of this harassment and threats; here Margaritha's work is an exception (albeit very partisan). Margaritha assumes a constant hostility: "In summa no Jew wants Keynem Christians." This contradicts the experiences of the Hebrew professor Johann Böschenstein , who was treated with respect in the Jewish community of Regensburg at the beginning of the 16th century.

The Regensburg Jewish community was, as in other cities, socially divided into two groups: on the one hand, the wealthy families, who almost alone bore the financial burdens that the Christian authorities imposed on the entire Jewish community and in return had limited legal security - on the other hand, the poor who, in the view of the Christian authorities, had no right of residence in the city and were at best tolerated there. Their share of the Jewish population is estimated for Erfurt and Nuremberg in 1485 at 25 to 50%. Some of them wandered from town to town and lived on the charity of their richer fellow believers. Conversions of Regensburg Jews to Christianity are known as early as the late 15th century. Then in 1500/01 Ascher Lemlein appeared in Venice and announced the imminent appearance of the Messiah ; the enthusiasm this sparked in German Jewish communities was followed by disappointment, and this crisis led to further conversions.

The hostility of the Christian population of Regensburg against the Jewish community increased more and more and in 1519 resulted in the expulsion of the Jews from Regensburg. As early as 1518, the city council applied to Emperor Maximilian to expel all Jews from the city with the exception of 15 families, who were under special imperial protection. In response, the Jewish community complained to the emperor that the Regensburg bakers - again - refused to sell them bread. The emperor rejected the request of the city of Regensburg, but he died in January 1519, and during the interregnum that followed, the city council enforced the expulsion of 600 to 800 Regensburg Jews within a few days. The preacher Balthasar Hubmaier acted as agitator .

Moated castle

At the end of the work The whole Jewish faith , Margaritha dated his baptism and put it in relation to the publication of his book (1530): “Outgoing in the ninth jar of my Widergepurth / wöllische zu Wasserburgk happen.” Accordingly, he settled in Wasserburg am Inn in 1521/22 to baptize. His wife also took this step.

Anthonius Margaritha was called a Lutheran by Joseph von Rosheim , and his catchphrase use of the term "gospel" as well as individual phrases such as "Christian believers heart" suggest that he assigned himself to the Reformation movement for a time; at the end of his life as a Hebrew teacher at the University of Vienna, however, he was undoubtedly a member of the Roman Catholic Church.

augsburg

In 1530 he came to Augsburg , where he published Der gantz Judisch Glaub in the same year . Margaritha spent the time of the Reichstag , which took place in the same year, in prison. The reason for his stay in the dungeon cannot be clearly explained. A dispute with Josel von Rosheim , who was able to refute Margaritha's work in a public disputation , will have had a decisive influence . Only at the instigation of the Viennese bishop Johann Fabri was he released from prison and banished from Augsburg.

Leipzig

Expelled from Augsburg, Margaritha went to Leipzig. In 1531 two editions of a revised version of Der gantz Jewish Faith appeared here . The author describes himself as a Hebrew teacher at Leipzig University. Another book by Margaritha, which was written during his time in Leipzig, is only known by its title: Psalterium Hebraicum cum radicibus in margine . It is the Hebrew text of the Psalms with additions. In Leipzig, Margaritha Bernhard Ziegler taught Hebrew, who later became known as a theology professor and as a Hebraist. The account book from the Leipzig Easter Market in 1534 shows that Anthonius Margaritha left Leipzig the following year and that his family remained there in poverty.

Vienna

Margaritha tried to use the interest in the Hebrew language awakened by humanism and to secure his livelihood with an academic activity. In Vienna, a chair for Hebrew was established in 1533 as part of a university reform. Margaritha accepted a call to Vienna and initially left her wife and small children in Leipzig, where they had to rely on public support. The permanent position did little to improve Margaritha's precarious financial situation, since the university was late in paying his salary. It was criticized that he could not hold his classes in Latin. Margaritha was still in contact with his family of origin. She offered him to repent, return to Judaism and take up a well paid teaching position abroad.

plant

Margaritha's main work, The Whole Jewish Faith , is an early ethnography of Judaism, but from the polemical perspective of the convert. As the son of a rabbi, Margharita presented herself to Christian readers as a “competent revelator of Jewish secrets.” Margaritha was less interested in making his conversion plausible or converting other Jews through his book; its addressees were Christians who lived in the neighborhood of Jews, as well as Christians who said, "The Jews are good / the Jews keep ire law then we." Voices that express respect for Judaism are, however, in contemporary Christian Literature rare. An anonymous report by Andreas Osiander is most likely to reveal such a position.

Margharita impressed on his readers that dealing with Jews was dangerous for them. For example, he warned against consulting Jewish doctors, "henceforth a standard issue of Protestant fear of Jews in the early modern period."

Margaritha drew a very tendentious picture of the Jewish Sabbath:

- “After this, the Jews do nothing all day. If they need to heat up the house, light the lights, milk cows, etc., take a simple-minded poor Christian who does this for them. They fame for this, they imagine that they are masters and that the Christians are their servants, they speak, they still have the true rule and rule, since the Christians served them in all their work and they are idle. "

A popular argumentation pattern that is highly dangerous for Jews can also be found in Margaritha - Jews as secret allies of the distant military enemy:

- “The Jews are very happy when a war arises in Christianity, especially through the Turks. Then they continue to pray against all Christian authorities. They cannot deny that their curse is on the current Christian kingdoms and empires. "

Margharita pursued a political intention with this accusation: princes and emperors were supposed to deprive the Jews of legal security and protection in the Holy Roman Empire . He imagined that if the Jews lived in misery, they would give up their belief in election and then they would convert to Christianity. In the early days of the Reformation, many aspects of the previous social order were put to the test, and this brought Margaritha's anti-Jewish proposals particular attention.

The church historian Thomas Kaufmann notes that around 1530 a new view of Judaism prevailed: Now it was no longer about attempts at conversion or a reflection on why these failed. Christian writers presented Judaism as a threat; the fear of the “word magic” Jewish prayer practice took the place of the “blood magic” late medieval fear of Jews. In line with this paradigm shift, accusations of ritual murder and host sacrilege no longer played a role and were also not represented or rejected by Margaritha and contemporary converts. In contrast to earlier authors, Margaritha does not criticize individual Jewish prayer texts as anti-Christian, but rather the entire Jewish worship service as such is directed against Christianity.

Reception history

The whole Jewish faith was particularly received by Protestant theologians and was coarsened and polemically exaggerated. Up until the 18th century, a distorted picture of the Jewish religion and customs emerged, backed up by information from an insider, who Margaritha presented herself as. The following authors depend on Margaritha's work for their knowledge of Judaism:

- Martin Luther , Von den Jüden und iren Lügen (1543);

- Martin Bucer , Kassel Advice (1538);

- Marcus Lombardus;

- Johann Buxtorf , Juden Schul (1603);

- Johann Christoph Wagenseil ;

- Johann Jacob Schudt ;

- Johann Andreas Eisenmenger .

Fonts (selection)

- Antonius Margaritha: The whole Jewish faith with sampt a thorough and warhafften announcement of all statutes, ceremonies, prayers, hymnical and public customs, which are held by Jews, through the whole year. With beautiful and well-founded arguments, you wyder faith. By Anthonium Margaritham ... describe and given to day . Heinrich Stayner, Augsburg 1530.

- Anthonius Margaritha: The Hebrew tongues ... Lector, explanation how from the holy, 53rd Capittel, of the nemigist prophet Esaie greenery, tried that the verhaischen Moschiach (wellicher Christ is) already came, the Jews onf khainen were waiting to change should, To comfort all frumen Christians, ...; Also a khurtze verleychung Bayder Testament , Wienn jn Osterreych 1534 , digitized, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Munich.

literature

- Stephen G. Burnett: Distorted Mirrors: Antonius Margaritha, Johann Buxtorf the Elder and Christian Ethnographies of the Jews . In: Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 25, No. 2. (Summer, 1994), pp. 275-287.

- Maria Diemling: “Christian Ethnographies” on Jews and Judaism in the Early Modern Age: The Converts Victor von Carben and Anthonius Margaritha and their presentation of Jewish life and the Jewish religion (dissertation) University of Vienna 1999, Permalink University Library Vienna .

- Maria Diemling: Chonuko - "kirchweyhe". The convert Anthonius Margaritha wrote about the celebration of Hanukkah in 1530 . In: KALONYMOS. Contributions to German-Jewish history from the Salomon Ludwig Steinheim Institute , Volume 3, 2000, Issue 4. pp. 1–3 (PDF)

- Maria Diemling: Anthonius Margaritha and his "Der Gantz Judisch Glaub" . In: Dean Phillip Bell, Stephen G. Burnett (eds.): Jews, Judaism and the Reformation in Sixteenth-Century Germany (= Studies in Central European Histories). Boston-Leiden, Brill Academic Publishers, 2006, pp. 303-333.

- Maria Diemling: Border Crossing: Conversion from Judaism to Christianity in Vienna, 1500-2000 . In: Wiener Zeitschrift zur Geschichte der Neuzeit 7, 2 (2007), pp. 40–63.

- Thomas Kaufmann: Religious and denominational conflicts in the neighborhood. Some observations on the 16th and 17th centuries . In: Georg Pfleiderer, Ekkehard W. Stegemann (Ed.): Religion and Respect (= Christianity and Culture . Volume 5). TVZ, Zurich 2006, pp. 139–172.

- Michael Thomson Walton: Anthonius Margaritha and the Jewish Faith: Jewish Life and Conversion in Sixteenth-Century Germany . Detroit 2012, ISBN 978-0-8143-3800-1 .

- Markus Thurau: The whole Jewish faith (Antonius Margaritha, 1530) . In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus. Anti-Semitism in Past and Present , Volume 8: Supplements and Register . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2015, pp. 207–209. ISBN 978-3-11-037932-7 .

- Peter von der Osten-Sacken : Martin Luther and the Jews. Newly examined on the basis of Antonius Margaritha's “The whole Jewish faith” (1530/31) . Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-17-017566-1 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Antonius Margaritha in the catalog of the German National Library

- Josef Mieses: The oldest printed German translation of the Jewish prayer book from 1530 and its author Anthonius Margaritha: a literary historical study (1916)

- Works by and about Antonius Margaritha in the JCS University Library Frankfurt am Main: Digital Collections Judaica

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michael Thomson Walton: Anthonius Margaritha and the Jewish Faith , Detroit 2012, pp. 1–5.

- ↑ Michael Thomson Walton: Anthonius Margaritha and the Jewish Faith , Detroit 2012, p. 6.

- ↑ Michael Thomson Walton: Anthonius Margaritha and the Jewish Faith , Detroit 2012, pp. 6-8.

- ↑ Michael Thomson Walton: Anthonius Margaritha and the Jewish Faith , Detroit 2012, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Michael Thomson Walton: Anthonius Margaritha and the Jewish Faith , Detroit 2012, p. 8.

- ↑ Michael Thomson Walton: Anthonius Margaritha and the Jewish Faith , Detroit 2012, p. 10 f.

- ^ Thomas Kaufmann: Denomination and Culture. Lutheran Protestantism in the second half of the Reformation century , Tübingen 2006, p. 120.

- ^ Maria Diemling: Grenzgängerum , 2007, p. 43.

- ^ Thomas Kaufmann: Denomination and Culture. Lutheran Protestantism in the second half of the Reformation century , Tübingen 2006, p. 120 f., Note 18.

- ↑ Anke Költsch: Jewish converts at the University of Leipzig in the pre-modern . In: Stephan Wendehorst (Hrsg.): Building blocks of a Jewish history of the University of Leipzig (= Leipzig contributions to Jewish history and culture . Volume 4). Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig 2006, p. 427–450, here p. 436–438.

- ↑ Maria Diemling: Grenzgängerum , 2007, p. 44.

- ↑ Maria Diemling: Chonuko - "kirch weyhe" , 2000, p. 1

- ↑ Markus Thurau: The whole Jewish faith (Antonius Margaritha, 1530) , Berlin / Boston 2015, p. 207.

- ^ Thomas Kaufmann: Denomination and Culture. Lutheran Protestantism in the second half of the Reformation century , Tübingen 2006, p. 121.

- ↑ Thomas Kaufmann: Religious and denominational conflicts in the neighborhood , Zurich 2006, p. 158.

- ^ Thomas Kaufmann: Denomination and Culture. Lutheran Protestantism in the second half of the Reformation century , Tübingen 2006, p. 125.

- ↑ Thomas Kaufmann: Religious and denominational conflicts in the neighborhood , Zurich 2006, p. 155.

- ^ Thomas Kaufmann: Denomination and Culture. Lutheran Protestantism in the second half of the Reformation century , Tübingen 2006, p. 126.

- ↑ Stephen G. Burnett: Distorted Mirrors , 1995, p. 286.

- ^ Thomas Kaufmann: Denomination and Culture. Lutheran Protestantism in the second half of the Reformation century , Tübingen 2006, p. 113.

- ↑ Markus Thurau: The whole Jewish faith (Antonius Margaritha, 1530) , Berlin / Boston 2015, p. 208.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Margaritha, Antonius |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Margaritha, Anthonius; Margaritha, Anton |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Jewish convert and Hebrew |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1492 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Nuremberg |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1542 |

| Place of death | Vienna |