Simon of Trento

Simon von Trient (regional German variants also Simmele von Trient; Simmerl von Trient, Italian variants Simone da Trento, beato / san Simonino, * around 1472 in Trient ; † March 26, 1475 ibid) was a member of the Roman Catholic Church as Martyr adored child who is said to have fallen victim to a ritual murder of Jews . His case is one of the most famous and long - lived anti - Judaist ritual murder legends . It was only finally rejected by the local bishop in 1965.

The torture process of 1475 against the Jews imprisoned as perpetrators served the operators around Prince Bishop Johannes Hinderbach as a basis and justification for pogroms against the Jews . 14 of the Jews arrested were executed, and several died as a result of the conditions of detention and torture. Several other ritual murder legends and sacrificial cults were created as a result of this fall.

Sources

Compared to other medieval ritual murder trials, the sources of the Trento Trial are very extensive. A total of eleven, partly complete, partly partial copies (eight of them contemporary) of the trial files have been preserved. In its appendix, Po-chia Hsia gives a source-critical overview of all trial files, eight of which are in Trento and one each in New York , Vienna and Vatican City . Wolfgang Treue strongly criticizes this representation, since several translation errors of the sources can be found in it. It should be noted here that these are not immediate transcripts, but that they were later made on the basis of direct trial transcripts and that they primarily reflect the point of view of the judges. The Trento archives and libraries also contain narrative and legal works and sources on cultivating cult in Trento (letters, notes, accounting books about donations in favor of Simon of Trient, wills, protocols about the miracles performed). Mainly the State Archives (Archivio di Statio di Trento (AST)), but also the Biblioteca Comunale di Trento (BCT), the Archivio del Capitolo del Duomo (ACDT) and the Archivio Arcivescovile (AAVT). Treue collected sources (letters, testaments, chronicles and literary sources) from relevant northern Italian cities ( Brescia , Mantua , Padua , Vicenza and Verona ) in order to reconstruct the diplomatic consequences of the process and Simon's cult outside of Trento. The history of reception can be grasped with increasing distance using chronicles and the narrative literature. In addition to the archival holdings, there are paintings and sculptures in churches, private houses and museums in Trento and the other cities.

The Trento Jewish Trial

course

On March 24, 1475, Simon's father, the master tanner Andreas Unverdorben and a member of the German minority in Trient, the Bishop of Trient, Johannes IV. Hinderbach, filed a missing person report for his son, who had disappeared the day before and had been sought unsuccessfully. This referred him to the Podestà of the city, Giovanni de Salis. Initially, an accident, more precisely falling and drowning in the tannery in Via del Fossato, now Via del Simonino, was suspected. This was obvious, because as a tanner, Andreas lived in the immediate vicinity of the river. On the same day, however, due to a rumor of ritual murder in the city, Andreas asked the Podestà to search the three houses of the Ashkenazi Jewish community, which numbered around thirty . The subsequent house search was unsuccessful, but shortly afterwards, members of the Samuel household, the Jewish community leader and pawnbroker , found Simon's body on March 26th ( Easter Sunday ). This was in a ditch under Samuel's house (on the site of the later Palazzo Salvadori, corner of Vicolo dell'Adige / Via Manci), which led to the river Adige . The Jewish community immediately informed the authorities. The next morning, during the initial examination carried out by the Podestà and the city governor Jakob v. Spaur (as the representative of Duke Sigismund as Count of Tyrol) the corpse bleed two of the numerous wounds in the presence of five Jews. In addition to inconsistencies in the statements about finding the dead, this was interpreted as an indication of guilt, which is why eight male members of the community (including the directors of the three Jewish households: Samuel from Nuremberg, Tobias from Magdeburg and Engel or Angelo from Verona) were immediately arrested and were imprisoned in the Torre Vanga .

Shortly afterwards, a medical report was obtained from the episcopal personal physician Giovanni Mattia Tiberino , the Trento physician Arcangelo Balduini and the surgeon Cristoforo de Fatis de Terlaco. The body had abrasions and puncture-sized punctures. The (Christian) doctors assumed a different cause of death than drowning, since the body contained little water. She interpreted the abrasions as shaving wounds inflicted with a knife, the stab wounds could have been inflicted by needle pricks. From the conclusions it can be seen that the thesis of ritual murder is already laid out in the reports. The medical reports were all the more important because they did not have the value of a simple testimony, but were considered a judgment. This led to the arrest of ten more members of the Jewish community on March 27. Witness statements obtained in the course of the investigation further incriminated the Jews. One testimony by an imprisoned thief was not very significant, and all other testimony was made by people who were all indebted to the Jews. According to medieval legal doctrine, the testimony of witnesses could therefore not be regarded as evidence, but at most as evidence that allowed the judges to imprison the Jews and continue to prosecute them.

From the beginning, the torture was not used to find out the truth, but to obtain confirmation of the ritual murder. This was achieved by insisting on key words such as “blood”, “martyrdom” and “hatred of Christians” and asking suggestive questions that already indicated the desired answer. The judge often included the expected confession in his question, which the defendant then only had to confirm. If the statements of the accused did not correspond to the preconceived notions of the judges, they first threatened with torture and then used the torture instruments until the accused gave the desired confessions. As a result, all of the main defendants submitted a largely identical version of the alleged ritual: Tobias, who was the only one allowed to leave his house during the Kartage while exercising his profession as a doctor , would have kidnapped Simon and hidden him. At Easter itself the torture and killing of the child would have taken place. In front of the synagogue in Samuels' house, he would have tied the neck of the child, who was being held on his knees on a chair by old Mosè, with a cloth so that his wailing could not be heard. Then Mosè would have cut the boy's jaw with pliers. Samuel and Tobias would have done the same, taking care to collect the child's blood in a bowl. All those present would then have stabbed the child with needles and cursed the Christians . Then the child would have incised the shin and at the same time a circumcision would have been carried out by old Moses. Here Simon was almost half dead and was only held upright in the chair by the arms crossed by the men. After Simon was again stabbed with needles and the curses were repeated against the Christians, he died after a total of half an hour of torture. The rite would have served to procure Christian blood for the Jews: to prepare the matzos and, mixed with wine, to bless the table during the Easter rite as a reminder of the ten plagues in Egypt, to heal wounds and to gain a beautiful complexion to protect women from premature births and miscarriages, and finally to counteract the stench that characterizes all Jews.

The forced confessions resulted in a total of 14 Jewish men being sentenced to death in June 1475 and January 1476. Through their decision to convert to Christianity, four death row inmates acquired the right to a “more humane” execution, that is, death by hanging rather than by burning. Moses, "the old man", died before the execution - probably under conditions of imprisonment and torture. The property was confiscated from all of them. The women of the Jewish community were initially placed under house arrest, but from October 1475 they were also interrogated under torture. According to their confession, they were also supposed to be cremated, but were pardoned and released from prison in January 1477 after their conversion (religion) to Christians. At least two of the women died in detention and torture. All remaining members of the Jewish community were expelled from the city.

The legality of the process carried out in Trento was controversial from the start and was interrupted several times. Nevertheless, on June 1, 1478, Hinderbach finally received confirmation from the Vatican for the formal correctness of the process.

Involved princes and rulers

Given the controversial nature of the Trent process, the attitude of the neighboring territorial princes was of great importance. Trento was a spiritual imperial principality , Hinderbach was prince-bishop . According to Italian law, the city was administered by an annually changing Podestà. As the sovereign of Tyrol, Duke Sigismund of Austria had a right of control and the bailiwick of Trento and wanted to expand this, together with other claims he had perceived, to a state sovereignty . According to Loyalty, he not only claimed it, but already owned it “not de jure but de facto”. In the Trent trial, which was therefore a domestic political matter for him, he initially sided with the accused. On his orders, the proceedings were suspended from April 21 to June 5, 1475. The bishop, mindful of his sovereignty, was little impressed by the rules and only followed the instructions in places. At the same time he tried in his correspondence with the Duke to convince him of the legality of the Trento trial. This shows how important the Duke's consent was to the Trent party. When he encountered unexpected resistance in Trento, he changed his mind and agreed to the process. However, there is no evidence of any personal admiration for Simons. Loyalty therefore describes the Duke's policy as determined by “pragmatism and opportunism”.

The behavior of the powerful neighbor of Trent, Venice, was also determined by a realpolitik, which aimed neither to endanger the security of the Venetian Jews nor to snub the supporters of the Trent process too much. From an initial condemnation of the trial in April 1475, which u. a. was determined by concern about its own trade and the important Jewish credits, the opinion of the Venetian government turned twice before, from April 1476, at least no public position was taken on the Trent Trial. For the advocates of the process, this meant that Venice had no allies, but with the growing number of supporters for the process, at least no real opponent had to be feared.

Other northern Italian territorial princes such as those from Urbino , Mantua, Genoa and Milan , in contrast to their immediate neighbors Venice and Tyrol , apparently saw no need to comment publicly on the process. They could not be influenced as far as possible, both internally and externally, but this - as the example of the pilgrimage of the ruling house from Mantua shows - did not stand in the way of Simon's private veneration.

Overall, none of the princes listed here reacted with direct measures against the Jews in their territories. On the other hand, there was no government that stood up for the Jews in Trento. They were essentially pragmatic. According to Loyalty, the absence of opposition on the part of the princes was an important prerequisite for the recognition of the Trent process. The emperor's complete silence was another. In this case, the latter probably followed the opinion of Duke Sigismund. He was not only a close relative, but also an important ally for a stable situation in the south of the empire. Emperor Friedrich should not have been interested in tensions with him.

The papal commissioner versus the Trent judge

In addition to the secular rulers, Pope Sixtus IV also became aware of the Trent Trial. It is no longer possible to reconstruct exactly how this took place, but apparently a number of Jews and some princes who were concerned about riots in their own territories turned to the Pope. It was also unclear whether the ecclesiastical inquisition law instead of the secular court was responsible for the matter. The Pope sent a papal commissioner to Trento, the Dominican Giovanni Battista dei Giudici, Bishop of Ventimiglia . Dei Giudici, a Dominican who was beyond any doubt of sympathy for Jews because of his sermons, was supposed to examine the legality of the proceedings. Hinderbach felt this - not untypical for a bishop in the late Middle Ages - as an erosion of his authority. Accordingly, the commissar encountered a hostile mood when he arrived in Trento on September 2, 1475. The Podestà refused to give him access to the trial files because they were not yet available in an authentic form. Although he was promised to submit it after four days, it took 17 days before he was first inspected. He was also not allowed to speak to the detainees. (He nevertheless got into conversation with the convert Wolfgang, who was temporarily released.) If he tried to hire people to establish communication between him and the imprisoned Jews from Trento, they would face severe penalties (up to the death penalty).

Dei Giudici realized that it would be impossible for him to carry out his task on the ground in Trento. After he came to the conclusion that the Jews were innocent and that Simon was not a martyr, he moved to the Venetian city of Rovereto , which was safe from the influence of Johannes Hinderbach , and made it the seat of his own court. Its main goal was to save the Jews who were still imprisoned. From the beginning of October he summoned the Podestà of Trento, the bishop and the cathedral chapter several times to court in Rovereto. He also sent a copy of papal letters, which gave him full power over every person of every class in Trent and forbade sermons on the cult of Simon in the name of the Pope. He also recalled several times a monitorium of the Pope, which ordered the lifting of the detention of Jews who were still imprisoned. Several times in his letters he threatens excommunication and other church punishments.

The people addressed in Trento reacted to the summons, decrees and threats by affirming that the Holy See did not have jurisdiction over the judiciary in Trento and by appealing to the Pope against the Commissioner's actions. He could be bribed by the Jews and, moreover, he could not be a competent judge in distant Rovereto. The torture also continued. These reactions show that the Commissioner made little impression with his demands. Nevertheless, Bishop Hinderbach was aware that his aim of providing evidence that the alleged crime of ritual murder by Jews in Trent was not an isolated case was in contradiction to the traditional position of the papacy. This had always defended the Jews against such accusations. Therefore, a lot of work has been done by Bishop Hinderbach to build up a collection of previous ritual murder cases and to get the accused to confess previous ritual murder cases. Dei Giudici had to realize that action was not possible from Rovereto either. His problem was that he lacked the means to carry out his assignment in practice. Although he was endowed with extensive powers from Rome, these had only limited influence on the events on site. He therefore left the city at the end of 1475 with a witness whom he had been able to interrogate and his trial protocols for Rome.

Given the contradictions between the Trent judgments and the results of the commissioner, the Pope appointed a cardinals commission to investigate the case in Rome. The representatives sent by Hinderbach to Rome, who increasingly promoted the Trento version, were decisive for the process of reaching a verdict. In addition, the conversion of confessing Jewish women in January 1477 was effective. They then called off their procurators who had represented their cause, officially admitted complicity in the alleged ritual murder and declared the conviction of their men to be justified. This event was not unexpected, but once again underlined the Trento point of view and left the Roman cardinals - even if they hadn't tended to do so before - hardly any prospect of a resolution directed against Trent's interests. In 1477 the commission completed its work. She confirmed the formal correctness of the procedure. The people of Trent were only able to achieve half a success with the verdict, however, as Simon was neither beatified nor recognized the guilt of the Jews. Dei Giudici became increasingly isolated during the Commission's investigations. He temporarily lost his seat in the Curia Society and had to take up work outside of Rome.

The perspective of the Jews

The main source for the Trent Trial are the trial files. These reflect the perspective of the inquisitors - especially the Podestàs and Bishop Hinderbach. A “voice” of the Jews can only be partially reconstructed in them. During the first interrogation, the Jewish prisoners are not tortured, but can only express their impressions. In this first stage of the process, before the torture, they were most likely to deliver their version of the events. Most of them came from (German) areas in which the belief in Jewish ritual murders was widespread (more than south of the Alps) and apparently knew what they could be accused of. It was precisely the fear of a ritual murder charge that led to the decision to voluntarily report the discovery of the body to the Podestà immediately when they found it in the moat under Samuel's house. The defendants initially believed in an accident that killed Simon. In view of the location and injuries to the corpse on the penis (which can be associated with circumcision), they soon suspected an attack on their community. In the case files, the defendants reproduce suspicions about possible culprits. In this context, Vitalis, a servant of Samuel, sued Johannes Schweizer. He was enemies with Samuel and therefore hid the corpse at the canal entrance of his opponent out of vengeance. Schweizer knew how to produce an alibi and in turn denounced Roper Schneider ("Judenschneider", "Schneider Jüd"), a friend of the Samuels family. They were released after a short term of two to three weeks.

The imprisoned Jews had little influence on the interrogations during the trial. One option available to them was to confess in order to gain respite. Finally there was an option to convert, which only saved the lives of the Jewish women. Since the process was intended to prove from the start that ritual murders were generally committed by Jews (and not only in Trento), it increasingly affected the Jewish minority outside of Trento. They intervened in Innsbruck with Duke Sigismund and as procurators in Rome. Procurators also lived in Rovereto and were in close contact with the papal commissioner. Their goals were partly different from those of the commissioner. Both parties were convinced of the innocence of the Jews. While Dei Giudici's goal was to release the Jews who were still imprisoned, the procurators' primary concern was the rehabilitation of those who had already been convicted. Only with their innocence could the ritual murder thesis be refuted.

The cult of Simon of Trento

Miraculous activities and pilgrimages in the 15th century

Simon's cult developed rapidly in Trento. Already on March 31st, the first miracle caused by Simon was registered by a notary: A citizen of Trento had been cured of many years of blindness by touching the corpse. More healed people appeared in the next few days, soon the pilgrims from more distant regions ( Bozen , Brescia, Feltre , Mantua, Vicenza, Belluna and Padua, Venice, Ferrara , Parma , Bergamo and Friuli ) increased. The status of the people who made a pilgrimage to Simon varied greatly and encompassed all classes of the population. In addition to the 'common people', intellectuals, priests , notaries etc. a. to Simon. In the miracle reports, which cover the period from March 31, 1475 to August 13, 1476, 128 miracles were recorded. The miracles did not stop after that, but were no longer recorded in protocols (still preserved today). Quantitatively, traditional domains of the efficacy of saints such as healing illnesses and rescue from drowning dominate. Due to the high income from the donations in the form of votive offerings and the trade in devotional items , various expenses were covered: the new building of the church of S. Pietro including a separate chapel for Simon, the renovation of Samuel's house, expenses related to the Jewish trial and his There were discussions (e.g. diplomats posted to Rome). From the contributions, however, the renovation of the episcopal castle was paid for and the silver mines in Pergine supported, which have nothing to do with the Simon cult. Connections between episcopal financial needs and the Trent process have also been assumed several times.

literature

The trial was accompanied by unilateral judges from Trent, mainly Bishop Hinderbach. Aside from his own work, he made use of his relationships with famous preachers (e.g. Michel Ecarcano), as well as with lawyers, from whom he received advice on his writings, and with humanists , whose stories and poems were widely circulated. Conversely, many humanists saw the process as a suitable opportunity for their literary development and took the initiative.

The earliest account of the Trent Trial is the report of the episcopal personal physician and employed court humanist Giovanni Mattia Tiberino. The text was written in the form of a letter to Tiberino's hometown of Brescia shortly after the start of the trial (probably in May). It is provided with sophisticated rhetoric in a humanistic style and also provides a fluid and - in the spirit of the proponents of the process - overall presentation of the process. The typeface became a great success and the most important propaganda work for the Trent Trial: Within a short time it reached 15 editions in Italy and Germany. Copies of the letter were made and the images of the following period were also based on the course of events at Tiberino. The many writings that followed were often based on Tiberino's letter and additionally provided the author's own details on the process and / or anti-Jewish ideas. Another important work was the first ever printed work in Trento on September 6th: the story of the Christian child murdered in Trento. In terms of content, it is based on the Tiberino letter, but is different in its artistic representation. It consists of twelve woodcuts and 13 chapters that comment on the images. The author is anonymous, but probably due to his good knowledge of (also later) events in the process in the vicinity of the Bishop of Trento.

The Trent ritual murder trial was also mentioned in the emerging printed chronicles of the 15th century, which were mainly acquired by intellectuals and interested well-heeled laypeople, and in which the Jews are portrayed as convicted criminals. At the beginning of the 1480s, the series of more detailed works on the Trial of Trent was over for the time being - apart from a few stragglers in Germany.

iconography

The production of the pictorial representations of Simon of Trento was considerable in the 15th century from 1475 to the turn of the century. The medium of the picture reached all levels of the population. Iconographic representations - apart from the handicraft products such as votive offerings - were located in Trento along a "station path" that led Simon's pilgrims to various places dedicated to his cult: the Simon Chapel in S. Pietro with the resting place of the corpse, one Chapel in the former house of Samuel and one in the house where Simon was born. Only a few pictures from the 15th century can be found in the immediate vicinity of Trento. A much greater density can be found in the northern Italian areas of the province of Brescia and in the areas between Verona and Vicenza, where the Franciscan Observance in particular liked to include Simon's story in its iconographic program in the churches. Representations of Simons are rare in German-speaking countries.

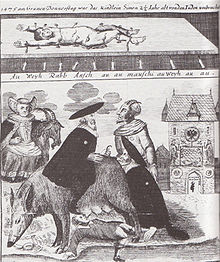

The first surviving representations of a passio - the story of Simon in a series of images - are the illustrations for the story of the Christian child murdered in Trento. Due to their early publication date and their distribution, the twelve woodcuts had a decisive influence on the further Simon iconography. Another picture cycle of 13 small woodcuts with the passio is contained in the translation of the Tiberino letter, published in Augsburg around 1476/1477, on the course of which as well as the woodcuts from Trent the representation is based. Few cycles of the passio can be found in frescoes and paintings that were very expensive. In 1478, Bartolomeo Sacchetto created frescoes for the new Simon Chapel in the former house of Samuels. Of these, only fragments of two paintings have survived today, on the one hand the consultation of the Jews among themselves and on the other hand the martyrdom can be recognized. Other surviving cycles consist of significantly fewer pictures such as four frescoes on the outer wall of the church of S. Andrea of Malegno in Val Camonica and in the church of S. Pietro of Brebbia . Cycles of the passio Simons are rather rare. More often, in iconography, depictions of Simon appear in a picture. In the first few years the martyrdom of Simon was preferred. This was done with the aim of portraying the crimes of the Jews as impressively as possible in order to underpin Simon's claim to veneration. The focus is mostly on Simon's martyrdom. Simon is held by Jews standing on a bench or he is sitting on Moses' lap. He is surrounded by several Jews who torture him in various ways. Attributes here are knife, tongs and awls for torture and a bowl that holds Simon's blood. This is sometimes alienated to a chalice based on the chalice for the blood of Christ. The earliest known version of the martyrdom scene contains the Trient pamphlet in its fourth illustration. Further representations of the martyrdom scene can be found in the Nuremberg Chronicle by Hartmann Schedel and the Augsburg Chronicle.

In addition, martyrdom (in Italy) was depicted in numerous frescoes. These were based on the illustrations from single-sheet prints . The single-sheet prints are all undated and without printer's note. Treue estimates the publication dates by comparing types to the period from 1475 to 1490. Four single-sheet prints each have survived from northern Italy and Germany. An Italian copperplate with the title Beato Simon martire dela Cita di Trento is unusual . The Jews are marked here with the round Jewish symbol , which, in contrast to other depictions, is not empty, but contains a miniature representation of a pig. Treue assesses this single-sheet print as “probably the earliest combination of ritual murder accusation and“ Judensau ”.” Finally, a polychrome wooden sculpture has been preserved that is now in the Diocesan Museum in Trento and was part of the main altar of the Church of S. Pietro. On this Simon's martyrdom was depicted as a counterpart to the martyrdom of the apostle Peter by arranging both side by side. (The martyrdom of Peter as well as sculptures of the Adoration of the Magi are no longer preserved.)

A type of illustration similar to the martyrdom scene is that of Simon victima, who shows Simon from a bird's eye view lying alone on a table surrounded by the instruments of torture. This form is already documented from the time of the trial, but remained rather rare. It is in some woodcuts, e.g. B. in some German Tiberino editions.

The type of illustration of Simon triumphans, of the risen Simons in an analogy to the risen Christ, largely replaced the other forms with the time lag to the event in Trent. Knowledge of martyrdom could be assumed to be known, instead the expression of glory became more important. This type was chosen so often because it could be best integrated into paintings that were not dedicated to Simon alone. In addition to the depiction of Simon triumphans, other saints appear in this way . He is represented several times together with Simon triumphans image 4 with the Virgin Mary - often in votive pictures. In the pictures, Simon is often naked. (The representation of the nude is important because it allows the wounds on the body to be shown.) Sometimes he wears a coat closed at the neck, and around his neck he usually wears the scarf that the Jews are said to have used to prevent him from screaming. In some pictures Simon holds the instruments of torture in his hands, in others the standard with the cross - this does not appear until around 1480, or the martyr's palm . The memory of the crime of the Jews is mostly limited to the reproduction of the instruments of torture. In some cases the Jews are directly integrated into the scene. In this type of representation, Simon stands on one or more of the defeated Jews.

16. – 20. century

After the cult's heyday in the years 1475 to around 1490, the cult of Simon of Trento experienced a phase of stagnation until around 1520, when it came to a standstill at the few local places of worship (Brescia, Padua, Venice). There are many reasons. First, the Austro-Venetian War in 1487 and later the War of the League of Cambrai in 1508 made pilgrimages risky. Second, interest in the Simon cult decreased. This is due on the one hand to the temporal distance to the former sensational story and on the other hand to the locality of the martyr, whose presence was primarily required at a central place of worship, which degraded all other places of worship to subordinate places. Thirdly, the decline in propaganda efforts - not least due to the death of Bishop Hinderbach in 1486 - was decisive.

This decline continued after 1520, which is why Treue writes of a phase of "regression" from the 1520s to the 1580s. Above all, the mismanagement and indifference within the cathedral chapter, which viewed Simon's cult as a pure source of income without bothering about the associated obligations, was decisive. The result was that revenues continued to decline. In spite of this, Simon von Trient was meanwhile an integral part of the knowledge base of numerous authors, by whom he is quoted in the most varied of literary genres - from marriage to crooks.

In the Council of Trent between 1545 and 1563, attempts were made to react to the Reformation and its effects by discussing new basic positions. The council briefly brought a larger crowd of pilgrims to S. Pietro and Simon's coffin, while cults in Trento were approaching their lowest point. Nevertheless, the Counter-Reformation piety was essential for the history of the Simon cult, because the promotion of the veneration of saints, which ensured a close relationship between the believers and “their” saint and thus also to the church, was very much in the interests of the Catholic Church. The official cult permission for Simon of Trient by Pope Sixtus V in 1588 should be seen in this context. With her Simon was allowed to be venerated as a blessed martyr. This officially confirmed a situation that in fact had existed for a long time.

The cult permit led to a stabilization of the cult, but the dimensions were initially limited. The actual renewal of the cult unfolded - following the general trends of the counter-Reformation veneration of saints - in the baroque 17th and 18th centuries. All of the cult sites were gradually redesigned and its presence in the city and its surroundings expanded through images. Simon's printed pictures - mostly of the Simon triumphans type - which served as devotional pictures and several mass foundations, testify to the renewed interest. In the literary field, a large number of sermons and narrative writings were printed in Italian, which testify to the revival of the cult. In the Tyrolean German-speaking area, despite the counter-Reformation movements, Simon von Trient would probably not have achieved widespread popularity without the cult of Anderl von Rinn , whose legend was written based on the events in Trento. In the 17th century a type of representation soon developed that showed the two martyr children side by side. In 1985 pageants in honor of Anderl von Rinn were held in the Tyrolean region, where boys were regularly costumed as Simon and Anderle.

In the 19th century both were used for anti-Jewish propaganda, as the writings of Pastor Joseph Deckert show. The publications resulted in a dispute between Deckert and Rabbi Josef Bloch, which was ultimately carried out in a court case, from which Bloch emerged victorious. (Dis) continuities of the cultural negotiations in the case are shown by an incident in the second half of the 20th century, when the alleged ritual murder was depicted on new glass paintings in the chapel of S. Pietro, which provoked violent protests, especially from the Jewish historian Gemma Volli . This incident prompted the Catholic Church to re-examine the trial files by the Dominican Eckert. The Congregation for Rites recognized in 1965 based on its results that there had been no ritual murder and regarded the cult as irrelevant. The beatification of Simon of Trent was repealed and the cult was prohibited.

research

In research, the Christian-Jewish relationship before the Trento Trial was long characterized as harmonious and the incitement of the Franciscan Minorite preacher Bernardino da Feltre was the trigger for the trial. This point of view is based on a biography of da Feltre, which was written around the 1520s. Its author, Bernardino Guslino, relied on the notes of the Secretary da Feltres. In recent research, this explanatory pattern has been criticized. Eckert sees da Feltre's sermons as one trigger of several. Treue comes to the conclusion that da Feltres' involvement in the object is very likely, but cannot be fully proven. Guslino's remarks would speak for a commitment. This referred to conversations about the Jews with Bishop Hinderbach, to da Feltres 'close relationship with the Podestà of Trient, who sought help from da Feltres' sermons in his jurisdiction, and to the sermons that da Feltre gave against the Jews in Trento. Nevertheless, it is too easy to portray Feltre as the sole trigger for the process and the interruption of the peaceful Christian-Jewish relationship. So z. For example, there are no contemporary documents on the role of Feltres in the Trento archives, which otherwise documented the Simon case in striking detail. Treue sees an essential (re) n factor in the meeting of two previously different lines of development: a German anti-Judaism , which had a long tradition and was represented by the German-born residents of Trento, met an expanding Italian one. For Quaglioni, this encounter represents a turning point in the history of Judaism and Christianity, which would usher in a more difficult social and legal situation for the Jews in the 15th century.

The Trento Trial is characterized by the fact that contemporaries argued violently about its course. The research justifies this with the geographical and political location of the city and the principality of Trento. Duke Sigismund intervened in the process in April 1475, which he could only legitimize through his claim to rule over the prince-bishopric. Pope Sixtus IV also decided to intervene - not a common occurrence. Although many popes had taken a stand against the accusations, none had intervened directly in a trial. This was made possible by the fact that Trento was a spiritual principality within the Italian sphere of influence. Loyalty gives several reasons for Dei Giudici's failure. First, the intervention was generally open to legal challenge, as the process was a secular procedure before the supreme court of a prince - the prince-bishop. Although it was potentially a crime against the Christian religion, the alleged perpetrators were not Christians, which is why it did not fall under ecclesiastical jurisdiction. Second, he would not have been able to use the authority given to him to seek secular help if necessary, because in Trento ecclesiastical and secular power were in one hand. No help was to be expected from the two territorial states Tyrol-Austria and Venice, between which Trento was located. The only really effective means would have been the excommunication and the related impeachment of Bishop Hinderbach by the Pope. However, this drastic measure would have met with protests and would also have required the consent of the emperor .

In Trento, this interference resulted in increasing identification with the process and increased efforts to defend the process. In addition to the diplomacy of Trent and the meticulous collection of data from alleged ritual murder cases, these were propaganda efforts. The success of this "propaganda campaign, which is unique in the Middle Ages" can be explained by the commitment of the Franciscan Observance, the use of the newly created book printing and the great interest in anti-Jewish documents. In addition, the location of Trient is once again decisive for Simon's cult. Located on the important north-south travel route, news quickly spread in both directions, and pilgrims to Rome made stops in Trento.

Finally, Simon von Trient is assigned an important role model for other cases - Anderl von Rinn, Sebastiano von Portobuffolé, Lorenzino von Marostica - and his role in confirming the existence of alleged Jewish ritual murder practices. He thus acted as a constant mediator of an anti-Jewish legend.

swell

- Augsburg: anonymous chronicle of Augsburg history, Chron. D. German cities 22 (Augsburg 3).

- Calfurnio, Giovanni: Mors et apotheosis Simonis infantis novi martiris, approx. 1487.

- History of the Christian child murdered in Trient, Trient, Albert Kunne, 1475.

- Martyrdom of Simon, wooden sculpture, late 15th century, Museo Diocesano Tridentino, inv. 3016.

- Schedel, Hartmann: Liber Chronicarum, Nuremberg, Anton Koberger, 1493.

- Tiberino, Giovanni Mattia: Letter to the city of Brescia (Reatio de Simone puero tridentino), Augsburg, Kloster Sankt Ulrich u. Afra, 1475.

literature

- Rainer Erb : The ritual murder legend. From the beginning to the 20th century. In: Susanna Buttaroni, Stanislaw Musial (ed.): Ritualmord. Legends in European History. Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2003.

- Anna Esposito: The stereotype of the ritual murder in the trials in Trent and the veneration of the "Blessed" Simone. In: Susanna Buttaroni, Stanislaw Musiał (ed.): Ritualmord. Legends in European History. Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2003, pp. 131–172.

- Eberhard Kaus: Simon of Trient. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL), Volume 33, Nordhausen 2012, Sp. 1263–1267.

- Ronnie Po-chia Hsia: Trent 1475 - Stories of a Ritual Murder Trial. Yale University Press, New Haven / London 1992. ISBN 978-0300068726 ( online ).

- German: Trient 1475. History of a ritual murder trial. S. Fischer, Frankfurt 1997, ISBN 3-10-062422-X .

- Diego Quaglioni: The Inquisition Trial against the Jews of Trento (1475-1478). In: Susanna Buttaroni, Stanislaw Musiał (ed.): Ritualmord. Legends in European History. Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2003, pp. 85–130.

- Wolfgang Treue: The Trento Jewish Trial. Requirements - Processes - Effects (1475-1588). Research on the history of the Jews Series A, Volume 4, in the series of publications of the Society for Researching the History of the Jews (GEGJ), Verlag Hahnsche Buchhandlung, Hanover 1996, ISBN 3-7752-5613-X ( online ).

- Markus J. Wenninger : The instrumentalization of ritual murder accusations to justify the expulsion of Jews in the late Middle Ages. In: Susanna Buttaroni, Stanislaw Musial (ed.): Ritualmord. Legends in European History. Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2003.

- Laura Dal Pra: L'immagine di Simonino nell'arte trentina dal XV al XVIII secolo, in: Bellabarba, Marco; Rogger, Ignio (ed.) Il principe vescovo Johannes Hinderbach (1465-1486) fra tardo Medioevo e Umanesimo, Bologna 1992, pp. 445-482. (Laura Dal Pra examined the iconography of Simon of Trent with a historical approach.)

- fiction

- Alexander Lohner : The Jewess of Trento. Structure, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-7466-2025-2

Web links

- Simon von Trient in the complete catalog of incandescent prints (GW number SIMON)

- Simon of Trient in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- musical-life.net

- Italia Judaica (Italian)

Individual evidence

- ^ Ronnie Po-chia Hsia: Trient 1475. History of a ritual murder trial. New Haven / London 1992.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: Der Trienter Judenprozess , pp. 179-182.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Judicial Trial , p. 180.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Judicial Trial , p. 26.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Judicial Trial , p. 339 f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Judicial Trial , p. 28.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Judicial Trial , p. 78.

- ↑ Eberhard Kaus: Simon of Trient. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL), Volume 33, Nordhausen 2012, Sp. 1263

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 92.

- ↑ Quaglioni, Diego: The Inquisition against the Jews of Trent (1475-1478), in: Buttaroni, Susanna; Musial, Stanislaw (ed.): Ritual murder. Legends in European History, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2003, p. 105.

- ↑ Quaglioni, Diego: The Inquisition against the Jews of Trient, p. 105ff.

- ↑ Esposito, Anna: The stereotype of ritual murder in the Trento trials and the veneration of the "blessed" Simone, in: Buttaroni, Susanna; Musial, Stanislaw (ed.): Ritual murder. Legends in European History, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2003, p. 138

- ↑ Esposito, Anna: The stereotype of ritual murder in the trials in Trent and the veneration of the "blessed" Simone, p. 140.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 94.

- ↑ Esposito, Das Stereotype des Ritualmordes, pp. 141f.

- ↑ Quaglioni, Das Inquisitionsverfahren, p. 91.

- ↑ Eberhard Kaus, Simon von Trient, Sp. 1265

- ↑ Eberhard Kaus, column 1266.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Judicial Trial , p. 204.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 91.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Judicial Trial , p. 205.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trienter Judenprocess and its consequences , Vienna 1995, pp. 95 and 205

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Judicial Process and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 206.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: Der Trienter Judenprozess and its consequences , Vienna 1995, pp. 206 to 209.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, pp. 210f.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 212.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 212f.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 86

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 95.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Judicial Trial , p. 86.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 96f.

- ↑ Quaglioni, Das Inquisitionsverfahren, pp. 97f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: Der Trienter Judenprozess , p. 203.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 97.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Judicial Trial , pp. 203f.

- ↑ Quaglioni, Das Inquisitionsverfahren, p. 98.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: Der Trienter Judenprozess , p. 144, p. 520.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 98.

- ↑ Quaglioni, Das Inquisitionsverfahren, p. 100.

- ↑ Esposito, Das Stereotype des Ritualmord, p. 132.

- ↑ Esposito, Das Stereotype des Ritualmord, p. 138.

- ↑ Esposito, Das Stereotype des Ritualmord, p. 135 .; Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 91f.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 92f.

- ↑ Eberhard Kaus, Simon von Trient, Sp. 1265.

- ↑ Esposito, Das Stereotype des Ritualmord, p. 136.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Judicial Trial , p. 126.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trienter Judenprocess and its consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 95; Wolfgang Treue: The Trento Jewish Trial , p. 205.

- ↑ Esposito, Das Stereotype des Ritualmord, p. 97.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: Der Trienter Judenprozess , pp. 231–248.

- ↑ ibid., P. 190.

- ↑ Esposito, Das Stereotype des Ritualmordes, p. 147.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: Der Trienter Judenprozess , p. 193.

- ^ Tiberino, Giovanni Mattia: Letter to the city of Brescia, Latin: Toledo, Archivo y biblioteca.

- ↑ ibid., P. 289, p. 293. For the composition of the letter and its detailed analysis, see ibid., P. 292f.

- ↑ see for an overview of the works ibid., P. 306ff.

- ↑ ibid., P. 295f .; Esposito, p. 149.

- ↑ u. a. the Nuremberg Chronicle of Schedel 1493, the anonymous Augsburger Chronik of 1546, and the Speiersche Chronik of 1476. see. for an overview of the chronicles, ibid., p. 339f.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 300.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 348.

- ↑ Ibid. Pp. 386-391.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 363.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 364ff.

- ^ Woodcut from: H. Schedel, Liber Chronicarum, Nürnberg, Anton Koberger, 1493, f 204v.

- ^ Wolfgang Treue: Der Trienter Judenprozess , pp. 367–371, p. 269.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Judicial Trial , p. 370f.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 367f.

- ↑ Wooden sculpture, late 15th century, Diocesan Museum of Trento.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 375.

- ↑ Strictly speaking, Simon has not yet been canonized, but he is venerated as such and his iconographic representation also makes a claim to it.

- ↑ Hans Klockner: Simon triumphans, wood relief, approx. 1495, Brixen, Diözesanmuseum.

- ↑ Ibid., SS 377-386.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 464f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Judicial Trial , p. 487.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 523.

- ↑ Ibid., Pp. 497-482.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 487ff. The bull is of particular importance because it is the first papal document in which one against Jews was recognized as appropriate. This set a fundamental precedent. Ibid., P. 490.

- ↑ ibid., P. 524.

- ↑ ibid., Pp. 497-509.

- ↑ ibid. Pp. 509-517; Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 99.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 516.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 100f.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and Its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 101.

- ↑ by Luca Ciamberlano, published by Pietro Stefanoni in 1607

- ↑ The so-called “Frankfurter Judensau” spread in single-sheet prints and copperplate engravings in the 17th century as an anti-Jewish disgrace; Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Jewish Trial , p. 375f.

- ↑ Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and its Consequences , Vienna 1995, pp. 88f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: Der Trienter Judenprozess , pp. 163–166.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: Der Trienter Judenprozess , p. 518.

- ↑ Quaglioni, Das Inquisitionsverfahren, p. 85.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: Der Trienter Judenprozess , p. 518ff .; Wenninger, Instrumentalization of Ritual Murder Accusations, p. 204.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: The Trient Judicial Trial , p. 518f.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Treue: Der Trienter Judenprozess , p. 521.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: Der Trienter Judenprozess , p. 524; Quaglioni, Das Inquisitionsverfahren, p. 85; Paul Willehad Eckert: The Trient Jewish Trial and its Consequences , Vienna 1995, p. 99; Esposito, Stereotype of Ritual Murder, p. 131.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Simon of Trento |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Simmele of Trento |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Child for whose death in 1475 Jews were held responsible as alleged ritual murderers |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1472 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Trent |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 26, 1475 |

| Place of death | Trent |