Burgus Visegrád-Lepence

| Burgus Visegrád-Lepence (Burgus Solva 23, Burgus Solva 35) |

|

|---|---|

| limes | Pannonian Limes |

| section | 3 |

| Dating (occupancy) | valentine |

| Type | Burgus |

| size | Core work: approx. 18.30 × 18.30 m |

| Construction | stone |

| State of preservation | Building remains secured under a temporary protective roof |

| place | Visegrád |

| Geographical location | 47 ° 45 ′ 57.8 " N , 18 ° 57 ′ 12.8" E |

| height | 108 m |

| Previous | Small fort Visegrád-Gizellamajor (southwest) |

| Subsequently | Visegrád-Sibrik Castle - Pone Navata (northeast) |

The Burgus Visegrád-Lepence is a small Roman military site , which was responsible for the control of a section of the Pannonian Danube Limes as well as for the regulated traffic on the adjacent military and trade route. After a watchtower (Burgus Solva 23) already known for the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD, a new, particularly massive Burgus (Burgus Solva 35) was built near it in the late 4th century AD . The border line, secured in its most extensive expansion phase with a dense network of further military stations, secured the Pannonian provinces on the opposite bank of the river, where the Germanic tribe of the Quadi settled. The excavated and secured remains of the Burgus are located near the Danube in the southwest of the historical center of the city of Visegrád, about 1.5 kilometers away, in Pest County in northern Hungary .

location

Both the mid-imperial watchtower and the Burgus were built as part of the close-knit security system on the lower slope on the Danube Bend . The traffic on the river and along the Limes Road could be observed from the two offset locations. The borderland on the opposite bank, controlled by Roman patrols , was also in the field of vision of the small military stations. In an emergency, the soldiers on duty there could send optical signals to the nearest larger garrisons. The extensive development of the border fortifications in this area, which was carried out at great expense, was due to the serious threat to Pannonia from the quadrupeds living on the opposite bank, which often appeared as a relentless opponent of Rome. Opposite the discovery sites at Visegrád-Lepence, on the north-western bank of the Danube, there is a large headland which, as a mighty spur of the surrounding hill country, bears the Sankt-Michaels-Berg, which the stream pressed into a narrow valley has to flow around in a wide arc. The southern and eastern shores of the Danube is directly behind the accreting find site loess terraces and the rising there Pilisgebirge , one from the Miozän derived Andesitformation limited. Short foothills of the mountains almost reach the narrow strip of alluvial land of the river. Due to the geological conditions, the rock material in the Pilis Mountains consists of volcanic weathered debris, finer and coarser andesite tuff , which is covered in some places by layers of loess and fine-grained tuff. Soil mechanical investigations indicated various river bed shifts in the floodplain of the Danube.

Research history

The exploration of the building remains on the right bank of the Lepence brook, which flows from the Pilis Mountains through the municipality of the city of Visegrád, was initiated by the preparatory work of the archaeologist Sándor Soproni (1926–1995). He suspected a Roman watchtower for this area. The first scientific excavations had become necessary in the course of an archaeological prospecting when extensive preparatory work for the construction of a Danube step seriously endangered the existence of the monuments along the river. During emergency excavations between 1986 and 1988, traces of settlement from the late Neolithic , the early Chalcolithic and the Late Bronze Age were recorded. In addition, a first Roman grave from the early principate came to light (grave 120 of the associated cremation cemetery) and traces of a settlement from the early and middle imperial period were found. The early medieval settlement by the Magyars included the remnants of free-standing ovens from the Arpad era . There was also a pit house next to it . A burial ground, which was located between the Burgus and the area of today's thermal baths, also belongs to the early Arpad settlement. The excavation of the late Roman Burgus finally took place between 1992 and 1997. There, too, an early árpáden period burial was found that was disturbed by modern road construction. After the excavations, the area under investigation between today's highway and the Danube was partially flooded and partially raised by filling. All excavations were carried out under the direction of archaeologists Dániel Gróh and Péter Gróf . The excavated northwestern part of the late antique Burgus was preserved for posterity in a preserved state.

In the course of a digital cataloging of the Hungarian monuments and works of art, the Burgus was recorded in September 2012 using a terrestrial laser scanner ( Leica HDS7000). The digital documentation also included the building inscription recovered from the Burgus and the three heads of ancient sculptures found there.

Building history

Burgus Solva 23

- Watchtower

The late Roman Burgus was preceded by a medieval watchtower. Its remains were discovered in the course of an archaeological prospecting , when extensive preparatory work for the construction of a Danube step endangered the existence of the monuments along the river. The area examined from 1986 to 1987 lay in the floodplain of the Danube and was located north and northeast of the Lepence brook. Overall, the topsoil and younger colluvia as well as fluvial sediments were extracted over an area of around 2500 square meters. Around 100 meters from today's highway, remains of the Roman wall came out of the ground near the shore. The middle-imperial stone tower foundation, known in older literature as watchtower 1 of Visegrád-Lepence , was 5 × 5 meters. According to the excavators, the stone substructure was built for a wooden watchtower. Its foundation had a wall thickness of 0.60 meters and an inner space of 3.60 meters. The ground level access was on the opposite side of the tower to the south-east of the river. A circular moat was dug around the tower, which was only of shallow depth and exposed in front of the tower entrance. Trenches of this type on guard towers from the Middle Imperial period are today often not viewed as defensive obstacles due to their nature, but rather as weather-related drainage and eaves trenches that were used to keep the structure dry. Immediately in front of the entrance, a layer of stone was uncovered that had been part of a Roman course horizon. The found material of the tower showed a large number of Roman roof tiles bearing the stamp of the LEG II ADI ( Legio II Adiutrix ) stationed in Aquincum . The term ante quem can be placed in the time before 214 AD on the basis of this stamp. Another stop to the dating is a recovered coin from the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus (193–211), which was still as brilliant as an uncirculated.

- Cremation field

Southeast of the watchtower - at the northeastern end of the ancient settlement - a Roman age cremation cemetery was uncovered in a 25 to 30 meter long strip along the northwest flank of today's country road . In this area, the modern traffic connection largely coincides with the Roman road route. The archaeologists and their collaborators uncovered 120 graves that dated to the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD. With the help of the finds, the occupation of the burial ground could be dated between 150 and 240 AD. The coinage originated from the reigns of Emperor Mark Aurel (161-180) to Maximinus Thrax (235-238). The time of the Severians (193–235) can be seen as the main focus of use . The remains of weapons were also found in the graves.

- Settlement findings

The cultural layer belonging to the findings of the 2nd and 3rd centuries could be recorded from the right bank of the Lepence brook over a total area of around 100 x 250 meters. Overall, settlement findings were found on both sides of today's road No. 11. The strength of the found-leading strata could be measured at around two to 2.20 meters. There was no pre-Roman settlement continuity at this location. A sterile barrier layer of 0.20 to 0.30 meters existed between the Roman strata and the observed strata of the Late Bronze Age urn field culture from the Váler group. These older settlement remains could be observed at depths of 1.20 to three meters. Due to the time and financial constraints, there was no way to examine the area more thoroughly. There were plenty of terra sigillata fragments in the Roman finds , with goods from the Rheinzaben and Westerndorf factories clearly predominating.

Burgus Solva 35

| 3d ideal reconstruction of the Burgus |

|---|

| Reka LOVAS, Katalin TOLNAI |

|

Link to the picture |

Opposite the Visegrád-Lepence thermal baths, the previously unknown remains of the Burgus Solva 35 (watchtower 2 of Visegrád-Lepence) came to light for the first time during the expansion of road 11 at the beginning of the 1980s. Its foundations are now on the right bank of the Lepence brook and a third are located directly under the roadway on the Danube side of this street. During the construction work, they were partially destroyed by a new canal system and partially buried unexplored under the embankment that was then applied to the route. The archaeologists Gróf and Gróh only found out about the events in 1992, as the responsible museum had not been informed during the construction work. In the same year, the scientists made a search cut along the highway and came across the first remains of the wall. A first excavation was necessary due to the construction of a parking lot on the site planned for autumn 1994. In the following year and then until 1997, almost half of the exceptionally well-preserved structure was exposed. The inclined, modern filling of the embankment prevented further investigations.

- Core plant

The Burgus Solva 35, which is still around 1.80 to 2.20 meters high, was only 40 meters away from the Burgus Solva 23. The core plant had a circumference of around 18.30 × 18.30 meters and a wall thickness of 1.60 to 1.66 meters. The masonry was listed as an opus incertum made of rubble stones. The Roman craftsmen carefully spread the mortar between the stone joints and then smoothed it. In this way they achieved a decorative wall structure. The corners of the core work were reinforced with cuboid cut stones. A slightly protruding substructure formed the architectural conclusion to the running horizon at that time. As with similar structures, for example at Burgus Leányfalu , the excavators uncovered four rectangular stone pillars in its interior, which were once built as additional supports for the rising floors and the roof. The foundation trench 1.30 meters deep on the masonry had almost vertical walls. The foundations anchored there were built on a bed of fine-grain fluvial gravel several centimeters thick . The foundations were even 1.50 meters deep on the stone pillars. The masonry was also carefully plastered on the surfaces of the invisible foundation walls. The investigation of the foundations also enabled a stratigraphic profile recording of the layers cut through during the Burgus building. Here the older Roman and prehistoric anthropogenic strata could be revealed . It turned out that when the northern pillar was erected, a previous furnace was destroyed. Above the stove was a fragment of terra sigillata and a grooved pearl in the profile. Findings were also secured on the inside of the southern foundation trench. There was a grayish-brown cohesive layer over the ground and a black stripe burned through it. The archaeologists uncovered a red-burned area 1.10 to 1.20 meters in size in this area. A regular 0.60 × 0.60 meter pit that was 0.40 meters deep also came to light. It contained burnt wood scraps and iron slag . The burned-out layer contained a few fragments of terra sigillata and other ceramic remains from the early Imperial period.

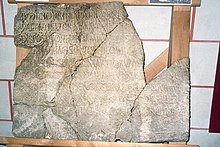

At the entrance facing the Danube, which was two meters wide, the threshold stone of the door, consisting of two parts, could still be uncovered in situ . Significant signs of use can still be seen on the threshold stone. Next to the entrance was a broken, datable building inscription from 371, three limestone heads from the 4th century and two lion figures. The heads broken off at the necks may have belonged to busts or statues. The most important portrait is that of a stately lady with earrings, reused as a spoiler , which was subsequently and roughly reworked. Obviously, the face should be given a masculine character. The head was then walled in in such a way that layers of mortar remained on the crown, chin and ears. This not only made the female hairstyle unrecognizable, but probably also the earrings. As later research turned out, the woman's head belonged to a full-figure grave sculpture from Aquincum that was made between 200 and 300 AD. The makeover was supposed to turn the head into a portrait of the emperor. Of the lion figures, one seated sculpture is almost undamaged, the other heavily destroyed. Remnants of red paint were found on the muzzle of the well-preserved specimen. It appeared to the excavators as if the building inscription belonging to the Burgus, which was discovered in 1997 two meters away in front of the entrance to the core work, as well as the figures had been hastily and subsequently added. The fall of the tower, possibly at the end of the 4th century, is attested by fire rubble. This homogeneous layer of rubble filled the entire interior of the core plant. Hardly any datable material was found in the Burgus. The excavators were surprised by the almost complete lack of ceramic products. The finds included two coins from the reign of Emperor Constantius II (337–361). also bronze coins from the 360s to 370s. In addition to a fragmented brick stamp of Terentius dux , several stamps of the subsequent Frigeridus dux could also be recovered from the rubble of Burgus .

- Enclosing wall and moat

The 0.80 to one meter thick enclosure wall was 6.40 meters from the southwest wall of the core plant. In contrast to the actual Burgus, this wall was built negligently. The remains of the entrance to the inner courtyard were visible on the western corner of the surrounding wall. This was 2.80 meters wide. As the light foundations on this gate suggest, it was probably particularly secured by a wooden construction on the inside. Around 15 to 15.50 meters from the southeast wall of the core plant, a profile cut was made through a gravel, stony stream bed layer. In this layer, a small section of the Spitz trench that once surrounded the structure was revealed.

- Building inscription

The Burgus was built by the Legio I Martia, which was set up during the reign of Emperor Diocletian (284–305) . The uncovered building inscription made of amphibole andesite, in which the carved letters still had red color, dates from the year 371 and reads:

Iudicio principali ddd (ominorum) nnn (ostrorum) Val [e] ntiniani Valentis

et Gratiani rrincipum maximorum dispositione {m}

etiam inlustris viri utriusque militiae magistri eouiti

comitis Foscianus p (rae) p [ae] legion] (osiorum)

una cum militibus sibi creditis h [unc bur] gum a fundentis

et construxit et ad sum (m) [am man] um operis

consulatu {s} Gratiano Augus [t] o to e [t Pr] obo viro cla / rissimo fecit pervenire

The text contains two typographical errors. Thus rrincipum correctly dissolves into principum and eouiti becomes equiti . Since the next watchtower at Visegrád quarry has an inscription from the year 372 and - in contrast to Burgus Solva 35 - exclusive stamps of Frigeridus were found there, the two Duces Terentius and Frigeridus are expected to change office in 371.

The remains of the foundations of the Burgus, which is located near a parking lot, have been restored, conserved and given a protective roof. The area is largely secured with a chain link fence.

Limes course between the Visegrád-Lepence castle and the Visegrád-Sibrik fort

| Route! Name / place | Description / condition | |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | Visegrád quarry (Burgus Solva 24) |

The following, freely accessible Burgus 24 (also known as watchtower 22), near a quarry south of Visegrád (Visegrád-Kőbánya), is also located behind the Danube bank road. The inside 8.90 × 8.90 meter stone tower foundation with its average 1.05 meter thick walls was extensively excavated after a test excavation in October 1955 to 1957 and preserved for the public in 1960. Its remains of Opus incertum on 1.25 to 1.35 meters thick foundation walls had first come to light a few years earlier in the course of an orchard planting. The building had a 1.80 meter wide entrance on the northeast side facing away from the Danube. A 1.30 meter long swelling stone was preserved here. A stone stove had been installed in the northeast corner of the tower interior. In addition, it was possible to uncover a rectangular support pillar that was subsequently built on the Roman running horizon, which once helped to support the floors and the heavy roof. A thin layer of rubble and fire was found on this massive central pillar. This led the excavators to conclude that the tower burned down again or damaged shortly after its completion - perhaps during the Quadruple incursion of 374 - but was immediately repaired afterwards. At a distance of 6.60 meters from the tower, a 4.50 meter wide and 1.87 meter deep trench was found. Immediately after the search excavation began, the first fragments of a 90 × 101.5 centimeter and 12.5 centimeter thick limestone inscription panel, which also came from the Legio I Martia and after the, were found in the rubble between the Burgus entrance and the eastern corner this structure was erected in 372. A total of 10 fragments could still be recovered, the upper right half has been lost to this day. In the text itself, the last four lines and the middle letters were missing in two lines. The reconstruction of the inscription was based on a similar copy from Esztergom , the content of which was only known from a work by the humanist Antonio Bonfini (around 1434–1503), who lived in the 16th century . Some typical late Roman linguistic peculiarities are also noticeable in relation to the content. The lost Eztergom tablet dates from the year 371 and was therefore erected at the same time as the inscription that came to light on Burgus Solva 35 between 1991 and 1994. Both finds show that at least the section between Estergom and Visegrád-Lepence could have been built within a year. In addition to Valentinian's coins, there were also several brick stamps from Dux Frigeridus as well as the stamps TEMP VR LXG ( L egio X G emina ) and TEMP VRS . TEMP VRS type stamps , which belong to the Valentine period, were also found at tower point 15 near Pilismarót-Duna melléke dűlő. Iudicio principali ddd (ominorum) nnn (ostrorum) [Valentiniani] |

| 3 | Visegrád Ferry (Burgus Solva 25) | The next 11 × 11 meter Burgus 25, also located behind the Danube road and close to the outflow of the Apát-kúti brook in Visegrád, has only been partially preserved. Its remains, examined in 1963, can be viewed in the underpass to the Danube ferry. |

| 3 | Visegrád-Sibrik (Pone Navata) | To the north-east of the last burgus are the remains of the Visegrád – Sibrik castle, which can be visited on a hill . |

Lost property

Important material from the excavations near Lepence is now in the Salomon Tower Museum , a branch of the Mátyás Király Múzeum in Visegrád. Among other things, a 1: 1 partial reconstruction of the entrance to Burgus Visegrád-Lepence, the two building inscriptions and small finds can be viewed there.

Monument protection

The monuments of Hungary are protected under the Act No. LXIV of 2001 by being entered in the register of monuments. The Roman watchtowers and Burgi as well as all the other Limes facilities are archaeological sites according to § 3.1 of the nationally valuable cultural property. According to § 2.1, all finds are state property, regardless of where they are found. Violations of the export regulations are considered a criminal offense or a crime and are punished with imprisonment for up to three years.

literature

- Sandor Soproni: Burgus building inscription from the year 372 on the Pannonian Limes. In: Studies on the military borders of Rome, lectures at the 6th International Limes Congress in southern Germany. Böhlau, Cologne / Graz 1967, pp. 136–141.

- Sándor Soproni : New research on the Limes stretch between Esztergom and Visegrád. In: Roman frontier studies 1979. 12th International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies. BAR Oxford 1980, ISBN 0-86054-080-4 , pp. 671-679.

- Dániel Gróh: Építéstörténeti megjegyzések a limes Visegrád környéki védelmi rendszeréhez. Building history remarks on the defense system of the Limes in the vicinity of Visegrád. In: A kőkortól a középkorig. Edition G. Lőrinczy. Szeged 1994, pp. 239-244.

- Péter Gróf, Dániel Gróh: Late Roman watchtower and statues from Visegrád-Lepence. In: Folia Archaeologica. 47, 1999, pp. 103-116.

- Péter Gróf, Dániel Gróh: The watchtower of Visegrád-Lepence. In: Budapest régiségei. 34, 2001, pp. 117-121.

- Péter Gróf, Dániel Gróh, Zsolt Mráv : Sírépítményből átalakílott küszöbkő a Visegrád-Gizella majori későrómai erődből (threshold stone from the late Roman fort from the late Roman fort of Visegrád-Gizella majori. In: Folia archaeologica. 49/50, 2001/2002, pp. 247-261.

- Zsolt Visy: The ripa Pannonica in Hungary. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 2003, ISBN 963-05-7980-4 , p. 51.

- Zsolt Visy: Definition, Description and Mapping of Limes Samples. CE Project "Danube Limes - UNESCO World Heritage" 1CE079P4. Budapest 2010. pp. 18-19 (Burgus Solva 35), 20-21 (Burgus Solva 24).

- Róbert Fülöpp, Gergely Buzás: A Visegrád-lepencei római őrtorony felmérése és elméleti reconstrukciója. Archaeologia - Altum Castrum Online, Mátyás Király Múzeum, Visegrád, 2013

Remarks

- ↑ a b c d e f Péter Gróf, Dániel Gróh: Late Roman watchtower and statue find at Visegrád-Lepence. In: Folia Archaeologica. 47, 1999, pp. 103-116; here: p. 103.

- ↑ Péter Gróf : Árpád-kori szabadban levő kemencék Visegrád-Lepencén - Outdoor ovens from the Árpád era in Visegrád-Lepence . In: Piroska Biczó (ed.): Dunai Régészeti Közlemények . Budapest 1989, pp. 57-65.

- ↑ a b c d Péter Gróf, Dániel Gróh: Late Roman watchtower and statues found at Visegrád-Lepence. In: Folia Archaeologica. 47, 1999, pp. 103-116; here: p. 107.

- ↑ Róbert Fülöpp, Gergely Buzás: A Visegrád-lepencei római őrtorony felmérése és elméleti reconstruction. Archaeologia - Altum Castrum Online, Mátyás Király Múzeum, Visegrád, 2013, p. 2.

- ↑ a b c d Zsolt Visy: The ripa Pannonica in Hungary. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 2003, ISBN 963-05-7980-4 , p. 51.

- ↑ a b c d e Péter Gróf, Dániel Gróh: Late Roman watchtower and statues found at Visegrád-Lepence. In: Folia Archaeologica. 47, 1999, pp. 103-116; here: p. 105.

- ↑ a b Péter Gróf, Dániel Gróh: Late Roman watchtower and statues found at Visegrád-Lepence. In: Folia Archaeologica. 47, 1999, pp. 103-116; here: p. 106.

- ↑ Fülöpp Róbert, Buzás Gergely; A Visegrád-lepencei római őrtorony felmérése és elméleti reconstruction. Archaeologia - Altum Castrum Online, Mátyás Király Múzeum, Visegrád, 2013, p. 5, fig. 4.

- ^ Péter Gróf, Dániel Gróh: Late Roman watchtower and statues found in Visegrád-Lepence. In: Folia Archaeologica. 47, 1999, pp. 103-116; here: p. 1112.

- ^ Péter Gróf, Dániel Gróh: Late Roman watchtower and statues found in Visegrád-Lepence. In: Folia Archaeologica. 47, 1999, pp. 103-116; here: p. 112.

- ^ Krisztina Szirmai: Imperial portraits in Aquincum . Exhibition catalog, 6th International Colloquium on Problems of Provincial Roman Art: 11. – 15. May 1999 Budapest-Aquincum, Budapest History Museum 1999, ISBN 963-7096-82-5 , pp. 70–71. See also: Woman in Tunica and Coat. The statue belonging to the head from Visegrád-Lepence, www.ubi-erat-lupa.org.

- ^ Péter Gróf, Dániel Gróh: Late Roman watchtower and statues found in Visegrád-Lepence. In: Folia Archaeologica. 47, 1999, p. 114.

- ^ Klaus Wachtel: Frigeridus dux. In: Chiron. 30, 2000, p. 913.

- ^ Dániel Gróh, Péter Gróf: Vízlépcsőrendszer és régészeti kutatás Nagymaros-Visegrád térségében. In: Magyar múzeumok 1995, 2. 1996, pp. 22–24 (in Hungarian); Klaus Wachtel: Frigeridus dux. In: Chiron. 30, 2000, pp. 905-914.

- ^ Péter Gróf, Dániel Gróh: Late Roman watchtower and statues found in Visegrád-Lepence. In: Folia Archaeologica. 47, 1999, pp. 103-116; here: p. 109.

- ↑ AE 3000, 1223 ; Building inscription of a Burgus , http://www.ubi-erat-lupa.org/ ; Epigraphic database Heidelberg

- ^ Sándor Soproni: The late Roman Limes between Esztergom and Szentendre. Akademiai Kiado, Budapest 1978, ISBN 963-05-1307-2 , pp. 51-55, Pl. 58,13, Pl. 66,1.

- ↑ Route = numbering follows Zsolt Visy: The Pannonian Limes in Hungary (Theiss 1988) and Zsolt Visy: The ripa Pannonica in Hungary (Akadémiai Kiadó 2003).

- ↑ Burgus Solva 24 at 47 ° 46 '32.53 " N , 18 ° 57' 57.53" O .

- ↑ CIL 03, 3653 .

- ^ Antonio Bonfini: Rerum Hungaricum , Posinii 1744, Dec. I Lib. 20

- ^ Sandor Soproni: Burgus building inscription from the year 372 on the Pannonian Limes. In: Studies on the military borders of Rome, lectures at the 6th International Limes Congress in southern Germany. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne-Graz 1967, pp. 136–141; here, pp. 138-139.

- ↑ Jenő Fitz (ed.): The Roman Limes in Hungary. Fejér Megyei Múzeumok Igazgatósága, 1976, p. 63.

- ^ Sándor Soproni: The late Roman Limes between Esztergom and Szentendre . Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1978, ISBN 963-05-1307-2 , p. 33.

- ^ Sándor Soproni: The late Roman Limes between Esztergom and Szentendre . Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1978, ISBN 963-05-1307-2 , p. 51.

- ↑ Kastell Visegrad Sibrik at 47 ° 47 '53.55 " N , 18 ° 58' 48.31" O .