Dari-Persian

| Dari Persian فارسی دری |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Afghanistan | |

| speaker | 12.5 million native speakers [1] and a further 10 million second and foreign speakers | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | Afghanistan | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

fa |

|

| ISO 639 -2 | ( B ) per | ( T ) fas |

| ISO 639-3 |

prs |

|

Dari ( Persian دری Dari , DMG Darī , [dæˈɾiː]) or Dari-Persian (فارسی دری Farsi-ye Dari , DMG Fārsī-ye Darī , [fɒːɾsije dæˈɾiː]), colloquially mostly simply Farsi (فارسی, DMG Fārsī , 'Persian', [fɒːɾsiː]), is a political term for the standard variety of the Persian language in Afghanistan and is related to Iranian Persian like the Austrian standard German to the German standard German . It is based on the Kabul dialect . In the Afghan constitution, Dari-Persian is one of the two official languages. The second official language is Pashtun (Pashto) . Dari-Persian is the language of the Persian-language media in Afghanistan and is the lingua franca between the ethnic groups. Overall, 80% of the people in Afghanistan speak Persian. Therefore, Persian is the most widely spoken language in Afghanistan and the mother tongue of around 25 to 50% of the Afghan population, around 10–20 million in all. However, that is only 15–28% of the approximately 70 million native Persian speakers worldwide.

To distinguish the Afghan standard from the Iranian, the Afghan government officially named it Dari (literally: "the courtly") in 1964. This term was common in the early Middle Ages (9th – 10th centuries) for the court language of Persian rulers. Therefore it is also referred to as Afghan Persian in many Western sources .

The term Dari officially refers not only to the Kabul dialect, but also to all dialects of the Persian language that exist in Afghanistan such as B. Herati (cf. Herat ), Hazaragi , Badachschani (cf. Badachschan ) or Aimaqi . The main differences between Iranian Persian and Dari-Persian can be found in the vocabulary and in the phonology, but this is irrelevant for mutual intelligibility.

history

The Persian language developed from Middle Persian , the official religious and literary language of the Sassanian Empire (224–651 AD), through some grammatical innovations (especially the omission of the obliquus and ergative ) and the inclusion of many Arabic and some Parthian words . Middle Persian is in turn the successor language of Old Persian in the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BC). In historical usage, Dari first refers to the Middle Persian court language of the Sassanids and then to the language at the court of the Samanids (819-1005), which referred to the Sassanids when they made the early New Persian the court and official language ( Persian زبان دربارى, DMG zabān-i darbārī , 'language of the (princely) court', short formزبان درى, DMG zabān-i darī , also darī ).

Persian was one of the most important governmental and diplomatic languages in the Ottoman Empire , Iran , Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent until the middle of the 18th century . As a result, the strength of Persia against the industrialized nations of Europe (many of which practiced imperialist policies in the regions where Persian was spoken ) declined . In the course of the constitution of Iran and Afghanistan as nation states, these states established a standard variety of Persian as the official language of their state in the early 20th century. This was based on the educated linguistic usage of the capital, i.e. Tehran or Kabul. For Persian, which is common in Central Asia, the Soviet state developed a third standard variety, Tajik , based on the language used by Samarkand . With the creation of the Tajik ASSR in 1929, this language was given permanent territory.

The naming of the Afghan standard variety of Persian as Dari belongs in this process of nationalization of Persian.

Surname

The name Dari as the official and court language of the Samanid Empire was added to the Persian language from the 10th century and is widespread in Arabic (compare al-Estachri , al-Moqaddesi and Ibn Hauqal ) and Persian texts.

"Fārsī" (formerly "Pārsī") means "language of the Iranian province of Fārs (formerly Pārs , ancient Greek Persis )", the cradle of the Persian language at the time of the Achaemenid Empire . There are different opinions about the origin of the word Dari . The majority of scholars believe that dari refers to the Persian word dar or darbār (دربار), which means "court". The name has appeared in literature since the Samanid period in the 9th and 10th centuries, when Persian was elevated to the court and official language. With the term darī ("court language") the Samanids wanted to tie in with the formal language at the court of the pre-Islamic Persian Sassanid Empire , to which they also referred otherwise. The original name of the language, Pārsī , on the other hand, is given in a communication attributed to Ibn al-Muqaffa '(quoted by Ibn an-Nadim in his book Al-Fehrest ).

Therefore, today's Afghan-Persian name "Darī" should emphasize the long tradition of Persian in Afghanistan. Before it was introduced as the name of the national language of Afghanistan, “Dari” was a purely poetic term and was not used in everyday life. This has led to a name dispute. Many Persian speakers in Afghanistan prefer the name Fārsī (German Persian ) and say that the term Dari was imposed on them by the dominant Pashtun ethnic group in order to distance Afghans from their cultural, linguistic and historical ties to the Persian-speaking nations. These include Iran and Tajikistan.

The in Afghanistan spoken Dari language is not with another language in Iran to be confused that there Dari or Gabri is called. This is about the dialect of living in Iran Zoroastrians .

Geographical distribution

Dari is one of the two official languages of Afghanistan (the other is Pashtun ). In practice, however, it serves as the de facto lingua franca among the various ethnolinguistic groups.

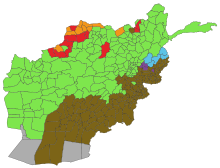

Dari is spoken by about 25-50% of the population of Afghanistan as their mother tongue, there are also other Persian dialects such as Hazaragi. Overall, 80% of the population of Afghanistan speak Persian . Tajiks , who make up about 27% of the population, are the main speakers. Hazara (9%) and Aimāiqen (4%) also speak Persian, but other dialects that are understandable for Dari speakers. In addition, many Pashtuns who live in Tajik and Hazaristan use Dari as their mother tongue. The World Factbook states that 80% of the Afghan population can speak the Dari language. Approximately 2.5 million Afghans in Iran and Afghans in Pakistan who are part of the Afghan diaspora speak Dari as one of their main languages. Migrants from Afghanistan in western countries also often speak Dari, Persian is one of the most important migrant languages in some German cities such as Hanover or Hamburg .

Dari dominates the northern, western and central regions of Afghanistan and is the common language in cities such as Mazar-i-Sharif , Herat , Fayzabad , Panjshir Province , Bamiyan and the Afghan capital Kabul , in which all ethnic groups to settle. Dari-speaking communities also exist in areas to the southwest and east of Pashtuns , such as the cities of Ghazni , Farah , Zaranj, Laschkar Gah , Kandahar, and Gardez .

Dialect continuum

The dialects of Dari, which are spoken in northern, central and eastern Afghanistan , for example in Kabul , Mazar-e Sharif and Herat , have different characteristics compared to Iranian Persian . The dialect of Dari spoken in western Afghanistan is hardly any different from the Iranian dialects. For example, the dialect of Herat shares vocabulary and phonology with Dari and Iranian Persian. Likewise, the Persian dialect in Eastern Iran, for example in Mashhad , is quite similar to the Afghan Herati dialect.

The Kabuli dialect has become the standard model of Dari in Afghanistan , as has the Tehrani dialect in relation to Persian in Iran . Radio Afghanistan has broadcast its Dari programs in Kabuli-Persian since the 1940s. Since 2003 the media, especially the private radio and television broadcasters, have been running their Dari programs with the Kabuli variant.

Differences between Iranian and Afghan Persian

There are phonological, lexical, and morphological differences between Afghan Persian and Iranian Persian. Apart from regional idioms, there are no significant differences in the written form.

Phonological differences

The main differences between standard Iranian Persian, based on the dialect of the capital Tehran , and standard Afghan Persian , based on the Kabul dialect, are:

- The so-called Majhul vowels , long Ē and Ō, coincide with long Ī and Ū in Iranian Persian, while they are still separated in Afghan-Persian. For example, the words "lion" and "milk" in Iranian Persian are both pronounced as shīr . In Afghan Persian, on the other hand, the lion is called shear and the milk is called shir . In Iran, the words zūd “fast” and zūr “force” both have a long U; in contrast, in Afghanistan these words are pronounced zūd and zōr .

- The diphthongs of the early classical Persian au and ai (as in “Haus” and “Mai”) have become ou and ey in Iranian Persian (as in English “low” and “day”), and that ou has always been in the last few decades more about an O. Dari, on the other hand, has preserved the old diphthongs. For example, is نوروز "Persian New Year" in Persian Iran as Nowruz and Afghan Persian as Nauroz pronounced and نخیر "NO (politely)" is nacheyr in Iran and nachair in Afghanistan.

- Short / i / and / u / are always lowered to [e] and [o] in Iranian Persian. This is not mandatory in Dari; there are both variants. When pronounced Iranian ou as O, it often coincides with the short O, while in Afghanistan it remains an Au.

- The short / a / tends more to Ä ([æ]) in Iran than in Afghanistan.

- In Iran, the letter W (و) is pronounced as a voiced labiodental fricative [v] (as in French vivre ). In contrast, Afghan Persian retains the (classic) bilabial pronunciation [w]. [v] is an allophone of / f / before voiced consonants in Afghan Persian. In some cases it appears as a variation of / b / together with [β].

- The very common so-called “not pronounced h” (pers. He-ye ġair malfūẓ ) at the end of the word (ه-) is pronounced as -e in Iran and -a in Afghanistan. Hence the Afghan city of Maimana in Iran is called Meymaneh .

However, Iranian television exerts a certain influence on the pronunciation, especially in western Afghanistan, so that the pronunciation in Herat is shifting in favor of the Iranian standard.

Lexical differences

First of all, there are locally different words for a number of terms, similar to "apricot" and "apricot" in German and Austrian. A shoe is called in Iranکفش, DMG kafš and in Afghanistan asپاپوش, DMG denotes pāpōš , and means “to deal with something” in Iranچیزی را تمام کردن, DMG čīz-ī rā tamām kardan (literally: “to finish something”), and in Afghanistanاز چیزی خالص شدن, DMG az čīz-ē ḫāliṣ šudan (literally: "to become free from a thing")

In Iran in 1935 a language academy was established under the name Academy for Persian Language and Literature ( Persian فرهنگستان زبان و ادب فارسی, DMG Farhangestān-e zabān wa adab-e fārsī ), which regulates Iranian Persian. Among other things, she tries to replace foreign words with Persian. This process continues to this day. In contrast, Afghan Persian was not regulated in Afghanistan, but much more energy was put into the further development of Pashto . Hence “student” in Iranian is Persian todayدانشجو, DMG dānešǧū , literally: " Seeker of knowledge", while in Afghanistan one continues to use the Arabic wordمحصل, DMG muḥaṣṣil used.

Older European foreign words tend to come from French in Iran and from English in Afghanistan due to the proximity of British India. For example, the socket is called in Iranپریز, DMG perīz (from French prize ), but in Afghanistanساکت, DMG sāket (from English socket ). Also the name “Germany” in Iran becomes Persian آلمان, DMG Ālmān , derived from the French “Allemagne”, whereas the same country is in Afghanistanجرمنى, DMG Ǧermanī (from English "Germany") is named.

The Dari language has a rich and colorful tradition of proverbs that deeply reflect Afghan culture and relationships, as demonstrated by U.S. Navy Captain Edward Zellem in his bilingual books on Afghan Dari proverbs collected in Afghanistan.

See also

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ The World Factbook. October 15, 2013, accessed December 30, 2019 .

- ^ Afghanistan. Accessed December 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Kirill Nourzhanov, Christian Bleuer: Tajikistan: A Political and Social History . ANU E Press, 2013, ISBN 978-1-925021-16-5 ( google.de [accessed December 30, 2019]).

- ↑ According to Ibn al-Muqaffā, Pārsī was the language spoken by priests, scholars, and the like; it is the language of the Fars . This language relates to Middle Persian. Regarding Dari , however, he also says: “It is the language from [the city] Madā'en. (the Sassanid capital, Ctesiphon ). It is spoken of by those who are at the king's court. [Your name] is associated with your presence at court. Among the languages for the people of Khorasan and in the east, the language of the people of Balkh is predominant. ”Quoted from DARĪ - Encyclopaedia Iranica. Accessed December 30, 2019 .

- ^ Dari language, alphabet and pronunciation. Accessed December 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Structural data of the city districts and city districts | Statistics office of the state capital Hanover | City and region statistics | Elections & Statistics | Politics | Living in the Hanover Region | Hannover.de | Home - hannover.de. Accessed December 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Dari - Persian. Accessed December 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Dari - Encyclopaedia Iranica. Accessed December 30, 2019 .

- ^ Persian Language. Accessed December 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Vrež Ḫāčāṭūrī-Pārsādānīyān: Farhang-e Fārsī-Darī, Darī-Fārsī; dar bar gīrande-ye tafāvothā-ye moujūd dar važegān-e Fārsī-ye emrūzī va Darī-ye mo'āṣer (Dictionary of Farsi-Dari and Dari-Farsi; list of the differences between the words in today's Farsi and contemporary Dari) , Tehran 1385 h.š. = 2006/7, p. 104

- ↑ Ibid., P. 99.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 35.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 17.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 3.