Rhine-Maasland

Rhein-Maasländisch (Dutch: Maas-Rijnlands ), also Rheinmaasländisch , has gained great importance in the Rhine-Maas triangle since the 12th century as a regional written language for medieval literature (mine novels), legal texts and chronicles, for which the Designation German Dutch (Dutch Duits Nederlands ) came up. Rhein-Maaslandisch is the counterpart to IJsselländisch , the language variant of German-Dutch that was native to the Overijssel region and was based on dialects of Lower Saxony .

Nevertheless, it can be observed that both variants were in a narrow dialect and written language continuum, which were almost identical on both sides of the dialect border (Westphalian or unit plural line). In the late 19th century, the originally apolitical-linguistic term "German-Dutch" was politicized by the national movement and used in the Pan- Germanic sense.

After 1945 it became common within Dutch and German studies to cover the area previously known as “German Dutch” with the terms “ North Lower Franconian ”, “ South Lower Franconian ” and “ Ostbergisch ” as well as “East Dutch” . After 1992, the terms Rhine-Maasland and IJsselländisch came up, thus avoiding the controversial question of whether the so-called writing languages of the Middle Ages and early modern times were “ Dutch ” or “ German ” on the part of German and Dutch studies .

origin

The term "Rhein-Maaslandisch" was introduced in 1992 by the Germanist Arend Mihm , analogous to "Ijsselländisch" , in order to have neutral and ideologically unaffected technical terms for the German and Dutch dialects of the border areas. These quickly gained acceptance within linguistics, so that it is now customary to use them in modern German and Dutch studies. However, some authors such as Claus Jürgen Hutterer (Die Germanischen Sprachen) and Werner König (dtv-Atlas zur deutschen Sprache) do not name this form of language until today, but deal with it under the chapter " Middle Dutch ", which is basically not wrong. Today, the south-eastern dialects of Lower Franconia , which are located in the Rhine-Maas triangle, are treated under the term "Rhine-Maasland" .

Geographical distribution area

Three isoglosses are used as the border lines of the Rhine-Maasland in Dutch and German studies : in the west the Diest-Nijmegen line or “houden-hold line”, in the south-east the Benrather line or “maken-making line” and in the north-east the Rhine-IJssel line or the unitary plural line . The former delimits the Rhine-Maasland dialects from the Brabant dialects , the latter from the Ripuarian and the latter from the Westphalian dialects . In the south it is bounded by the Germanic-Romance language border from Walloon .

Written language and dialects

To prevent mistakes: When Meuse-Rhenish is a pure writing ( written language ) to a firm language or a lingua franca of upscale items for decrees, regulations and official correspondence. This applied in the eastern Lower Franconian language area, but had to be distinguished from the spoken dialects of the Lower Rhine region. As well as the scripts written in “Official German” today, there were regional and local Lower Franconian dialects in the Middle Ages in addition to the written language, which in the late Middle Ages developed into the similar dialects on both sides of the German-Dutch border in modern times.

Replacement of Latin

Rhine-Maaslandish gradually replaced Latin, which had been used primarily for enactments until then. In the absence of spelling and grammatical rules, the spelling of place to place and from writer to writer varied; the same town clerks changed their spellings over time, which z. B. the linguist Georg Cornelissen described in his book "Little Lower Rhine Language History" using examples from cities in the region.

While in the Geldrisch-Klevian area - due to historical regional borders after the reorganization of the empire by Emperor Charles V - the written language tended to be more similar to today's Dutch , the influence of " Ripuarian " spreading from the electoral Cologne was noticeable in the areas further south .

Text examples

The following excerpts show the “proximity” of the Rhine-Maasland language to today's Dutch and to the Platt spoken on the German Lower Rhine :

- From an alliance letter dated 1364 from the Count of Kleve to the Dukes of Brabant, Jülich and the city of Aachen (available in the public state archive in Düsseldorf):

- At dyn gheswaren des verbunts the hertoghen van Brabant, van Guilighe and the stat van Aken onsen gůeden vrynden. Wi Greve van Cleve begheren u teweten, gůede vrynde, op uwen letter in the ghii ons scryvet van den verbonde, dat uwe heren die .. hertoghen van ... Brabant end van Guiligh, dye stat van Aicken end die ridderscaff ghemaickt hebben omme noytsaken (Necessary matters) wille van alrehande unmitigated, those in the lands gheschien, end mede van heren Walraven onsen neve, heren van Borne, dat her Walraven, onse neve, in langhen tiiden by ons niet gheweest en is, but soe wovere he by ons queme (came), we would like to report end onderwiisen nae onsen, dat he bescheit neme end gheve van onsen lieven here the hertoghe van Brabant. Voert guede vrynde want ghii scryvet van alrehande misdedighen invited the onthalden neither end worth in the land, en is ons nyet kůndich; kůnd wi the fact that the ingress would be af vernemen, of uytgheghaen, that soude wi like to na onsen so besceidelich iin doen, dat ghiit with gůede nemen soudt. Oeck soe siin wi van daer baven vast aenghetast end ghebrant, daer wi but the waerlich nyet monkey enweten, van wylken steden of sloeten ons dat gheschiet sii. Got bewaer u guede vrynde altoys. Contr. tot Cleve op den Goedesdach na sent Lucien dagh.

- From a "weather report" recorded in 1517 by Johann Wassenberch's Johanniter Chaplain in Duisburg:

- In the selven jair op den XVden (15th) dach yn den Aprijl, ende was doe des goedesdachs (derivation from Wodan's day = Wednesday) nae Paischen (derivation from “Passover” = Easter), van den goedesdach op den donredach (derivation von Donars Tag = Thursday) yn der Nacht, wastz soe calt, dat alle vruchten van allen boemen, van eyckelen, van noethen, van kyrssen, van proemen (plums), van appelen etc. neyt uytgescheyden (nothing except) vervroren end verorven ( frozen to death and spoiled), want sy stoenden yn oeren voellen blomen (full bloom). Item (all the while) all the vynstocken froze up end withered, off (or) sy burned were. End (and) dair schach great ruinous pity.

- There are documents handed down from the Herrlichkeit Hüls (district of Krefeld) from the 14th century onwards, but they differ from the spoken language , the local Hölsch Plott . Here is the extract from an inheritance in 1363 between the knights Matthias von Hüls and his brothers Geldolf and Johann:

- I Mathys van Hulß, Mr. Walravens Soen ... I announce and give all Luiden onder my seal ... that I with volcomenen Rade ind will miner maege ind gelken with Geldolp ind with Johan, minen Broederen ... so what could be the right ones my van minem Vader sturven sien ind hierna from miner Moder Frouwe Stynen van Hulß indignantly ind fall na oeren dode ...

Fonts used

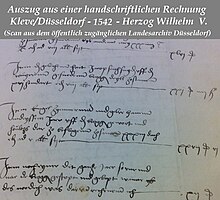

The handwritten documents (the modern in a personalized by each writer were written down Sütterlinschrift removed resembling) cursive . On old calculations it can also be found that up to the 16th century no "Arabic" numerals - which are in common use today - were used, but the old Roman numerals consisting of letters (letter sequences for numbers - the number "0" was unknown and only became through Adam Ries introduced). These Latin numbers appear to us today as handwritten "alienated" so that they, like the manuscripts themselves, are barely legible or understandable for inexperienced users.

The Textura font , as found in late medieval documents, was used for printed publications ; from the 16th century also the fracture similar to it .

Position within the Lower Franconian region

While Standard Dutch developed into national and written languages over several language levels ( Old Dutch , Middle Dutch and New Dutch ) and the Afrikaans derived from New Dutch , from the 18th century the Lower Franconian dialects receded in German territory in favor of Dutch . For a long time , the German Lower Rhine was considered a Dutch language area, although the authorities at the time (especially the Kingdom of Prussia ) tried to establish New High German as the sole written language .

"Niederrheinischer Sprachkampf"

With the establishment of New Dutch as a preliminary stage of today's Dutch (16th century), the former importance of Rhine-Maasland declined on the German Lower Rhine: On the one hand, it was given up in favor of Dutch, which mainly affected the former duchies of Kleve and Geldern . Second, it fell mainly on its southern borders under the influence of the language from Cologne spreading NHG : So that had Archdiocese of Cologne in 1544, a regional variant of the NHG as a lingua franca introduced. This soon showed its effects on the law firms in Moers, Duisburg and Wesel, among others. However, this "high German written language" could be used in some areas, e.g. B. in Geldrisches Oberquartier , due to the ties to the House of Habsburg, only very slowly. For a longer period of time, German and Dutch coexisted in some cities (including Geldern, Kleve, Wesel, Krefeld) and decrees were issued in both written languages.

From the 18th century, the linguistic separation between the (German) Lower Rhine and the (Dutch) Maas region was finally completed. The respective high-level and written languages went their separate ways. Spoken dialects, however, outlasted the new borders and persisted into modern times.

When the Lower Rhine became French in 1804, France introduced French and German as the official languages, which was not particularly popular with the population. With the help of the two large churches ( Roman Catholic and Reformed Church ), she began to adhere doggedly to Dutch, and in the following years it regained urban areas that it had lost to German. However, the Diocese of Münster (like the entire Archdiocese of Cologne ) pushed German, which put the Lower Rhine Catholics against the Archdiocese. Within the supporters of Dutch, two factions emerged which were identical to the denominational groups: The Catholics of the former duchies of Kleve, Geldern and Jülich favored a Flemish - Brabant variant , the Reformed a Brabant- Dutch variant. In 1813/15 the Kingdom of Prussia got its Rhenish territories back, introduced New High German as the sole official language in 1815/16 and established the Rhine Province there in 1822 .

The only official language of the Rhine Province was German and the authorities began to take action against the use of Dutch. In 1827, for example, the use of Dutch was officially forbidden in the then administrative district of Münster and only permitted to a limited extent as the church language of the Old Reformed ( Grafschaft Bentheim ). But since the middle of the 19th century there has been a rich regional and local dialect literature - written according to the personal orthographic peculiarities of the respective scribe; In addition, the Lower Rhine dialects between Kleve and Düsseldorf were cultivated in dialect circles and plays. But around 1860 the " Germanization process " was considered complete, as Dutch had now been displaced with the exception of minimal remains. Nevertheless , the dialect literature flourished through the “ Low German Movement ”, the North German “language wing” of the Volkish movement , which also claimed the Dutch language area for itself. Today there are numerous small-scale and local dialects in the Rhine-Maas triangle ; It is not uncommon for dialect boundaries to cut through the urban areas that have been newly structured in the course of regional reorganization.

See also

- Dialects and languages in North Rhine-Westphalia

- Lower Rhine

- Kleverlandisch

- Limburgish

- Rheinberger Platt

literature

- Georg Cornelissen 1995: De dialecten in de Duits-Nederlandse Roerstreek - grensdialectologischer bekeken (= Mededelingen van de Vereniging voor Limburgse Dialect- en Naamkunde , No. 83). Hasselt; also in: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/corn022dial01_01/index.htm (March 18, 2007).

- Georg Cornelissen 2003: Small Lower Rhine Language History (1300-1900): a regional language history for the German-Dutch border area between Arnhem and Krefeld : met een Nederlandstalige inleiding. Geldern / Venray: Stichting Historie Peel-Maas-Niersgebied, ISBN 3-933969-37-9 .

- Michael Elmentaler, The history of writing in the Lower Rhine. Research project of the University of Duisburg, in: Language and Literature on the Lower Rhine , Series of the Niederrhein-Akademie Vol. 3, 15–34.

- Theodor Frings 1916: Middle Franconian-Lower Franconian studies I. The Ripuarian-Lower Franconian transition area. II. On the history of Lower Franconian in: Contributions to the history and language of German literature 41 (1916), 193–271 and 42, 177–248.

- Irmgard Hantsche 2004: Atlas on the history of the Lower Rhine (= series of publications by the Lower Rhine Academy 4). Bottrop / Essen: Peter Pomp. ISBN 3-89355-200-6 .

- Uwe Ludwig, Thomas Schilp (red.) 2004: Middle Ages on the Rhine and Maas. Contributions to the history of the Lower Rhine. Dieter Geuenich on his 60th birthday (= studies on the history and culture of Northwestern Europe 8). Münster / New York / Munich / Berlin: Waxmann, ISBN 3-8309-1380-X .

- Arend Mihm 1992: Language and History on the Lower Rhine, in: Yearbook of the Association for Low German Language Research , 88–122.

- Arend Mihm 2000: Rheinmaasländische Sprachgeschichte from 1500 to 1650, in: Jürgen Macha, Elmar Neuss, Robert Peters (red.): Rheinisch-Westfälische Sprachgeschichte . Cologne etc. (= Low German Studies 46), 139–164.

- Helmut Tervooren 2005: Van der Masen tot op den Rijn. A handbook on the history of vernacular medieval literature in the Rhine and Maas area . Geldern: Erich Schmidt ^, ISBN 3-503-07958-0 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Irmgard Hatsche: Atlas for the history of the Lower Rhine , series of publications by the Niederrhein Academy Volume 4, ISBN 3-89355-200-6 , p. 66

- ↑ cf. also the language map "Written dialects in Middle High German and Middle Dutch times", dtv atlas on the German language, p. 76

- ^ Georg Cornelissen: Small Lower Rhine Language History (1300-1900) , Verlag BOSS-Druck, Kleve 2003, ISBN 3-933969-37-9 , pp. 19-61

- ↑ Dieter Heimböckel: Language and Literature on the Lower Rhine , Series of publications of the Niederrhein Academy, Volume 3, ISBN 3-89355-185-9 , pp. 15–55

- ^ Stadtarchiv Düsseldorf, archive directory - Dukes of Kleve, Jülich, Berg - Appendix IV

- ^ Georg Cornelissen: Small Lower Rhine Language History (1300 - 1900) , Verlag BOSS-Druck, Kleve 2003, ISBN 3-933969-37-9 , p. 32

- ↑ Werner Mellen: Hüls - a chronicle . Verlag H. Kaltenmeier Sons, Krefeld-Hüls, 1998, ISBN 3-9804002-1-2 , p. 105 ff

- ↑ Georg Cornelissen: Little Lower Rhine Language History (1300 - 1900) , Verlag BOSS-Druck, Kleve 2003, ISBN 3-933969-37-9 , pp. 62–94

- ↑ Dieter Heimböckel: Language and Literature on the Lower Rhine , Series of publications by the Niederrhein Academy Volume 3, ISBN 3-89355-185-9 , pp. 15–55