Equal Protection Clause (United States)

The Equal Protection Clause is a clause in the text of the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution . The clause, which came into force in 1868, provides that "no state [...] may deny anyone [...] within its jurisdiction the same protection under the law".

A major motivation for this clause was to confirm the equality provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 . They guaranteed that all citizens would have the guaranteed right to equal protection under the law. As a whole, the Fourteenth Amendment marked a major shift in American constitutionalism by adding far more constitutional restrictions to the states than they did before the Civil War .

The meaning of the equality clause is controversial and inspired the well-known phrase Equal Justice under Law . This clause was the basis for the decision of the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). This helped to eradicate racial segregation . It also created the basis for numerous other decisions aimed at preventing discrimination against members of different groups.

While the equality clause itself only applies to state and local actors, the Supreme Court in Bolling v. Sharpe (1954) decided that the Due Process Clause of the 5th Amendment to the Constitution nevertheless sets up various equivalent protection requirements for the US federal government through reverse incorporation .

text

The Equal Protection Clause can be found at the end of Section 1 of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws . [Emphasis not in the original] "

“All those born or naturalized in the United States and subject to its governance are citizens of the United States and the state in which they are resident. No state should enact or implement laws that limit the privileges and freedoms of citizens of the United States, and no state should take away anyone's life, liberty, or property, except through due process, under the law, nor deny anyone within their territory the same protection of the law. "

history

From the declaration of independence to the civil war

The concept of legal equality had been entrenched in America since the Declaration of Independence, it did not mean that equality was part of everyday life or legal practice. Before the amendments during Reconstruction , which included the Equal Protection Clause , were passed, there was a variety of resistance to black rights in America. Black people were considered inferior and until the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified it was legal to keep them as slaves. Even free blacks had no legal rights after one of the most notorious Supreme Court rulings of all time. He claimed that blacks in America had no constitutional rights to invoke in society or in court. Prior to this decision, there was nothing that theoretically prevented free black Americans from accessing their legal rights. In the decision of Dred Scott v. Sandford's 1857 Supreme Court, however, set a precedent whereby blacks, free or enslaved, had no legal rights within America.

In retrospect, many historians see this court decision as a point of no return that put the United States on the road to civil war. This later led to the ratification of the Reconstruction constitutional amendments, under which the Equal Protection Clause is located. Before and during the Civil War, the southern states banned public speaking from union-friendly citizens, opponents of slavery, and northerners in general because the Bill of Rights did not apply to the states . During the Civil War, many of the southern states revoked and banned whites from citizenship; in fact, they were thereby expropriated.

Shortly after the Union's victory in the American Civil War , the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was introduced and passed in accordance with Article V of the United States Constitution , which was then ratified by the states in 1865 and abolished slavery. As a result, many former Confederate States in America issued so-called Black Codes after the war , which severely restricted the rights of blacks to own property (land and numerous forms of driving ) and to conclude contracts. Such codes also imposed harsher criminal penalties for blacks than for whites.

Because of the inequality imposed by the Black Codes , the Republican-controlled Congress passed the Civil Rights Act 1866 . The law stipulated that all persons born in the United States be citizens (contrary to the Supreme Court decision of Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) ) and required that "citizens of all races and colors [...] be full and equal Share in the benefits of laws and procedures on the safety of people and property, as whites [already] do. "

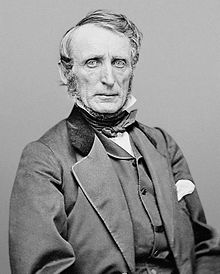

President Andrew Johnson vetoed the Civil Rights Act 1866 over concerns about whether Congress had the constitutional authority to make the law . These doubts were a factor in the fact that Congress would become involved in drafting and debating the future Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In addition, Congress wanted to protect white unionists who were personally and legally attacked in the former confederation. The effort was led by radical Republicans from both Houses of Congress, including John Bingham , Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens . The most influential of these men was John Bingham; he was the lead author and author of the Equal Protection Clause.

The southern states were against the Civil Rights Act. In 1865, however, Congress exercised its power under Article I, Section 5, Clause 1 of the Constitution to be "the Judge of the ... Qualifications of its own Members". He expelled the southerners from Congress, stating that their states, which had rebelled against the Union, could not elect members to Congress. It was this fact - the fact that the fourteenth amendment was passed by a “ rump legislature ” - that allowed Congress to pass the fourteenth amendment. The adoption of the amendment by the former Confederate States was imposed as a condition for their re-entry into the Union.

Adoption in Congress

Since the return to originalist interpretations of the constitution, what the constitutionalists intended when ratifying the reconstruction changes has been disputed. The 13th Amendment did away with slavery. To what extent he protected other rights was unclear. After the 13th Amendment, the South began adopting black codes : these were restrictive laws designed to keep black Americans in a position of inferiority. The 14th Amendment was passed by Republicans in response to the proliferation of black codes . Its adoption was irregular in many ways. At first there were several states that rejected the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. However, after new governments were formed there after the reconstruction , they accepted the addition. There were also two states, Ohio and New Jersey, which approved the amendment and later passed resolutions that repealed that amendment. Cancellation of the adoption by the two states was deemed inadmissible, and both Ohio and New Jersey were added to the list of states that were ratifying the constitutional amendment.

Numerous historians argue that the 14th Amendment was not originally intended to give citizens far-reaching political and social rights, but merely to consolidate the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act 1866 . While it is agreed that this was a major reason for ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment, many historians take a broader view. Accordingly, the Fourteenth Amendment was always intended to ensure equal rights for all people in the United States. Charles Sumner relied on this argument when he used the 14th Amendment as the basis for extending the rights of black Americans. Although the Equal Protection Clause is one of the most cited ideas in legal theory, little attention was paid to it when the 14th Amendment was passed.Instead, the main tenet of the Fourteenth Amendment at the time of its ratification was the Privileges and Immunities Clause . This clause was intended to protect the "prerogatives and freedoms" of all citizens, which now also included blacks. The scope of this clause was considerably restricted after the Slaughterhouse Cases . In these it was stated that the prerogatives and freedoms of a citizen were only guaranteed at the federal level and that it was an overstretching of the clause to impose this standard on the states. Even in this hesitant decision, the court still recognized the context in which the Amendment was passed: it found that knowing the grievances and injustices that the 14th Amendment was intended to address is key to understanding its implications and legal consequences its ratio. With the restriction of the Privileges and Immunities Clause , the legal arguments to protect the rights of black Americans became more complex. As a result, the view turned to the equal protection clause .

More than one version of the clause was considered during the debate in Congress. The first version:

"The Congress shall have power to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper to secure ... to all persons in the several states equal protection in the rights of life, liberty, and property."

Bingham said about this version: "It confers upon Congress power to see to it that the protection given by the laws of the States shall be equal in respect to life and liberty and property to all persons." The main opponent of the first version was Congressman Robert S. Hale of New York, despite Bingham's public assurances that "under no possible interpretation can it ever be made to operate in the State of New York while she occupies her present proud position." Hale eventually voted for the final version. When Senator Jacob Howard presented this final version, he said:

“It prohibits the hanging of a black man for a crime for which the white man is not to be hanged. It protects the black man in his fundamental rights as a citizen with the same shield which it throws over the white man. Ought not the time to be now passed when one measure of justice is to be meted out to a member of one caste while another and a different measure is meted out to the member of another caste, both castes being alike citizens of the United States, both bound to obey the same laws, to sustain the burdens of the same Government, and both equally responsible to justice and to God for the deeds done in the body? "

The 39th Congress of the United States introduced the Fourteenth Amendment on June 13, 1866. One difference between the original and the final version of the clause was that the final version spoke not only of "equal protection" but of "the equal protection of the laws". John Bingham said on this in January 1867: "No State may deny to any person the equal protection of the laws, including all the limitations for personal protection of every article and section of the Constitution ..." By July 9, 1868 three passed Quarter of states (28 out of 37) have the amendment. At this point the Equal Protection Clause became applicable law.

Early story after ratification

In a speech on March 31, 1871, Bingham said that the clause meant that no state could deny anyone "the equal protection of the Constitution of the United States ... [or] any of the rights which it guarantees to all men", nor could withhold "any right secured to him either by the laws and treaties of the United States or of such State. At that time the meaning of equality varied from one state to another."

Four of the original thirteen states never passed a law banning multiracial marriage , and many other states were divided on this issue as they rebuilt. In 1872 the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that the state prohibition of mixed marriage violated the "cardinal principle" of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Equal Protection Clause . Almost a hundred years would pass before the US Supreme Court resolved the Alabama ( Burns v. State ) case in the Loving v. Virginia followed. In Burns , the Alabama Supreme Court ruled:

"Marriage is a civil contract, and that character alone is dealt with by the municipal law. The same right to make a contract as is enjoyed by white citizens, means the right to make any contract which a white citizen may make. The law intended to destroy the distinctions of race and color in respect to the rights secured by it. "

In the field of public schooling, no state actually required separate schools for blacks in the era of Reconstruction . However, some states (e.g. New York) left it to the local districts to set up schools that were considered separate but equal . In contrast, Iowa and Massachusetts had outright banned segregated schools since the 1850s.

Likewise, some states were more favorable than others for the legal status of women; New York, for example, has given women full property, parental and widow rights, but not the right to vote, since 1860. No state or territory allowed women to vote in the United States when the Equal Protection Clause came into effect in 1868. In contrast, African-American men had full voting rights in five states at the time.

Gilded Age and the Plessy Decision

In the United States, 1877 marked the end of reconstruction and the beginning of the Gilded Age . The first really groundbreaking decision of the Supreme Court on the same protection was the decision of Strauder v. West Virginia (1880).

A black man convicted of murder by an all-white jury opposed law in West Virginia that banned blacks from participating in juries. The exclusion of blacks from the jury, so the court, was a denial of equal protection for black defendants, since the jury "drawn from a panel from which the State has expressly excluded every man of [the defendant's] race." At the same time, the Court explicitly allowed sexism and other forms of discrimination, saying that states "may confine the selection to males, to freeholders, to citizens, to persons within certain ages, or to persons having educational qualifications. We do not believe the Fourteenth Amendment was ever intended to prohibit this. ... Its aim was against discrimination because of race or color. "

The next major post-war case was the Civil Rights Cases (1883), which examined the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The law stipulated that all persons should have "full and equal enjoyment of ... inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement". In its reasoning, the court explained the " state action doctrine ", according to which the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause only apply to actions carried out by the state or otherwise "sanctioned in some way". Banning black people from attending theater performances or staying in inns was "simply a private wrong". The judges of the Supreme Court of the United States of America, John Marshall Harlan , wrote a dissenting opinion, saying "I can not resist the conclusion did the substance and spirit of the recent amendments of the Constitution have been sacrificed by a subtle and ingenious verbal criticism." Harlan went on to argue that since (1) "public conveyances on land and water" use public roads, and (2) innkeepers have "a quasi-public employment" , and (3) "places of public amusement" to be allowed under the laws of the states, the exclusion of blacks from the use of these services is an act sanctioned by the state.

Years later, Judge Stanley Matthews wrote the judgment of the Court in Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886). In it, the word "person" from the section of the 14th Amendment to the US Supreme Court has been given the widest possible meaning:

"These provisions are universal in their application to all persons within the territorial jurisdiction, without regard to any differences of race, of color, or of nationality, and the equal protection of the laws is a pledge of the protection of equal laws."

Thus, the clause would not be limited to discriminating against African Americans, but would also extend to other races, skin colors, and nationalities, such as (in this case) legal aliens in the United States who are Chinese citizens.

In his most controversial Gilded Age interpretation of the Equal Protection Clause, Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Supreme Court upheld a Jim Crow Act of Louisiana, which prescribed segregation of blacks and whites on railroad tracks and required separate carriages for members of both races. The Court, through Judge Henry B. Brown , ruled that the Equal Protection Clause was intended to defend equality in civil rights , but not equality in social institutions. All that was required of the law was therefore reasonableness , and the Louisiana Railroad Act abundantly met that requirement, for it was based on "the established usages, customs and traditions of the people." Judge Harlan issued a minority vote. "Every one knows," he wrote,

“That the statute in question had its origin in the purpose, not so much to exclude white persons from railroad cars occupied by blacks, as to exclude colored people from coaches occupied by or assigned to white persons ... [I] n view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens in this country. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. "

Such an "arbitrary separation" according to race, according to Harlan, is "a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution." Harlan's philosophy of constitutional color blindness would ultimately continue to prevail, especially after World War II.

It was also during the Gilded Age that a Supreme Court ruling contained a headnote from John C. Bancroft, a former president of the railroad company. Bancroft, who served as the reporter of the rulings of the United States Supreme Court , pointed out that companies are "persons" while the actual court ruling itself avoided certain statements about the Equal Protection Clause that apply to companies. However, the legal concept of corporate personhood precedes the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the clause was used to abolish many of the laws governing corporations. However, since the New Deal , such overrides have become rare.

Between Plessy and Brown

In Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (1938), it was about Lloyd Gaines , a black student at Lincoln University of Missouri , one of the traditionally black colleges in Missouri . He applied for law school admission to the all-white University of Missouri . Since Lincoln did not have a law school, he was denied admission because of his race alone. The Supreme Court ruled, using the Plessy Principle, that a state that offers legal education to whites but not to blacks violated the Equal Protection Clause .

In Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) showed the court an increased willingness to view racial discrimination as unconstitutional. The Shelley case concerned a privately signed contract that banned the people of the Negro or Mongolian race from living on a certain piece of land. The court appeared to be against the spirit, if not the exact wording, of the Civil Rights Cases , stating that a discriminatory private contract itself could not violate the Equal Protection Clause , but judicial enforcement of such a contract could; after all, so the reasoning of the Supreme Court, the courts are part of the state.

The accompanying cases decided in 1950 by Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents paved the way for a number of school integration cases. In McLaurin , the University of Oklahoma had accepted the African American McLaurin, but restricted his activities there: he had to sit separately from the rest of the students in the classrooms and the library and could only eat at one specific table in the cafeteria. A unanimous court through the Chief Justice of the United States Fred M. Vinson said that Oklahoma had withheld McLaurin the equal protection of the laws :

"There is a vast difference — a constitutional difference — between restrictions imposed by the state which prohibit the intellectual commingling of students, and the refusal of individuals to commingle where the state presents no such bar."

The current situation, Vinson said, was the previous one. In Sweatt , the court considered the constitutionality of the Texas state system of law schools , which trained blacks and whites in separate institutions. The court (again by Chief Justice Vinson and again unanimously) declared such a school system to be unconstitutional - not because it separated students, but because the separate institutions were not the same . They lack "substantial equality in the educational opportunities" offered to their students.

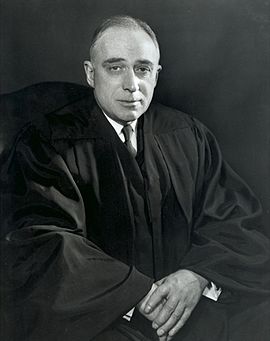

All of these cases, as well as the aforementioned Brown decision, were negotiated by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People . It was Charles Hamilton Houston , a Harvard Law School graduate and law professor at Howard University , who began advocating racial discrimination in federal courts in the 1930s. Thurgood Marshall , a former Houston student and future United States Solicitor General and Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court , joined him. Both men were undoubtedly exceptionally gifted lawyers. Most of their success was due to their ability to select suitable cases for judicial challenge.

Brown and the aftermath

In 1954, the contextualization of the Equal Protection Clause would change forever. The Supreme Court itself recognized the gravity of Brown v. Board on. He also recognized that a non-unanimous decision would pose a threat to the role of the Supreme Court and even to the country. By the time Earl Warren became Chief Justice in 1953, Brown had already come before the court. When Vinson was still Chief Justice, there had been a preliminary vote on the case at a conference of all nine judges. At that point the court was divided. The majority of judges voted that the school separation would not violate the equal treatment clause. However, through persuasion and flattery - he had been a hugely successful Republican Party politician before joining the court - Warren was able to convince all eight associate judges to agree and declare segregation in schools unconstitutional. In that judgment, Warren wrote:

“To separate [children in grade and high schools] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone ... We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. "

Warren advised other judges, such as Robert H. Jackson , not to publish concurring opinions ; Jackson's draft, which appeared much later (1988), contained the following statement: "Constitutions are easier amended than social customs, and even the North never fully conformed its racial practices to its professions". The Court reopened the discussion on how to implement the decision. The Brown II decision, adopted in 1954, concluded that the problems identified in the previous opinion were local and that the same was true of their solutions. The court therefore transferred jurisdiction to the local school boards and trial courts that originally tried the cases. ( Brown was actually a merger of four different cases from four different states). The trial courts and local authorities were told that they should desegregate "with all due speed".

Partly because of this enigmatic formulation, but mostly because of the self-proclaimed massive resistance in the South to the desegregation decision, racial integration did not begin until the mid-1960s, and then only to a minor extent. In fact, much of the integration in the 1960s came in response not to Brown but to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Supreme Court intervened several times in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but its next big desegregation decision came in only in Green v. School Board of New Kent County (1968) met in which Judge William J. Brennan , who wrote for a unanimous court, rejected a freedom of choice school plan as inadequate. This was an important decision; freedom-of-choice plans were common responses to the decision in Brown . According to these plans, parents could choose whether they wanted to send their children to a formerly white or a formerly black school. However, whites almost never chose to attend schools with traditionally black identities, and blacks rarely attended schools with white identities.

In response to Green , many southern boroughs replaced freedom of choice with geographic-based school plans; as residential segregation was widespread, little integration was achieved. In 1971 the court approved desegregation busing in the Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education as a remedy against segregation; three years later, however, in the case of Milliken v. Bradley (1974) overturned a minor court ruling requiring the transportation of students between school districts rather than just within one district. Basically, Milliken put an end to the Supreme Court's rulings on lifting segregation in schools; however, until the 1990s many federal courts remained involved in cases aimed at lifting segregation in schools; many had started as early as the 1950s and 1960s.

The limitation of busing in Milliken v. Bradley is one of several reasons cited to explain the inadequate educational equity in the United States. According to various left-liberal authors, the election of Richard Nixon in 1968 meant that the executive branch no longer stood behind the constitutional obligations of the court. In addition, the Court itself ruled in the San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez (1973) that the Equal Protection Clause allows a state - but does not oblige it - to provide equal funding for all students within the state. The decision of the court in Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925) allowed families to de-register from public schools in spite of "inequality in economic resources that made the option of private schools available to some and not to others", as Martha Minow put it.

American public school systems, especially in the major metropolitan areas, are still largely de facto segregated. Be it because of Brown, be it because of the actions of Congress, be it because of social changes: The percentage of black students who attend mostly black school districts declined somewhat until the early 1980s. After that, this percentage began to rise again. By the end of the 1990s, the proportion of black students in the school districts, which were mostly attended by minorities, had roughly returned to the level of the late 1960s. In Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 (2007) the court found that if a school system was racially disadvantaged by the government on the basis of social factors other than racism, the state was not as free to integrate schools as if it were itself responsible for the racial imbalance. This is particularly evident in the charter school system, where parents can choose which school their children attend; based on the services offered by this school and the needs of the child. It seems that race continues to be a factor in the choice of charter school .

Applicability to the US Federal Government

According to its text, the clause only restricts state governments. However, the due process clause of the fifth constitutional amendment , since Bolling v. Sharpe (1954), interpreted as imposing some of the same restrictions on the federal government:

"Though the Fifth Amendment does not contain an equal protection clause, as does the Fourteenth Amendment which applies only to the States, the concepts of equal protection and due process are not mutually exclusive."

In Lawrence v. Texas (2003) the Supreme Court added:

"Equality of treatment and the due process right to demand respect for conduct protected by the substantive guarantee of liberty are linked in important respects, and a decision on the latter point advances both interests"

Some academic voices have suggested that the court's decision regarding Bolling should have been made for other reasons. For example, Michael W. McConnell argues that Congress never "required that the District of Columbia schools be segregated by race". According to this view, the racial segregation of schools in Washington DC was unauthorized and therefore unconstitutional.

Graduated exam and groups

Despite Brown's undoubted importance, much of modern equal protection jurisprudence has emerged from other cases, although there is no consensus as to which other cases these are. Many academic voices hold that the opinion of Judge Harlan Stones in United States v. Carolene Products Co. (1938) included a footnote that marked a major turning point in equal protection jurisprudence , but this claim is controversial.

Whatever its exact origins, the basic idea of the modern interpretative approach is that more judicial control of alleged discrimination will be triggered when it concerns fundamental rights (e.g. the right to procreate). In a similar way, stronger judicial control is triggered if someone has been the victim of alleged discrimination precisely because he belongs to a suspect classification (e.g. to a single race). This modern doctrine was introduced in Skinner v. Oklahoma (1942) developed. It states that certain criminals should be deprived of their fundamental right to procreate:

"When the law lays an unequal hand on those who have committed intrinsically the same quality of offense and sterilizes one and not the other, it has made as invidious a discrimination as if it had selected a particular race or nationality for oppressive treatment."

Until 1976, the Supreme Court usually dealt with discrimination in such a way that it applied one of two possible standards of control: on the one hand, so-called strict scrutiny (if it was a question of a suspicious class or a fundamental right), or on the other hand, the much weaker rational basis review . Strict scrutiny means that a contested law must be narrowly tailored in order to serve a compelling interest and must not have a less restrictive alternative. In contrast, the rational basis scrutiny only requires that a contested law must be reasonably connected to a legitimate state interest.

In the case of Craig v. Boren , the Court added in 1976 an additional level of control, called intermediate scrutiny , to gender discrimination added. The court may have added other levels by now, such as: B. the so-called enhanced rational basis scrutiny.

All this is as tiered referred (stepped) verification. This has many critics, including Judge Thurgood Marshall , who advocated a "range of test standards in reviewing discrimination" rather than discrete levels. Judge John Paul Stevens argued for only one level of control as there was "only one equal protection clause ". The multi-stage strategy developed by the Court aims to reconcile the principle of equal protection with the fact that most laws necessarily discriminate in some way.

The choice of the standard of examination can decide the outcome of a case. The strict scrutiny standard is often described as "strict in theory and fatal in fact". In order to choose the right standard of examination, Judge Antonin Scalia asked the court to identify rights as fundamental or classes as suspect objectively, rather than relying on more subjective factors.

Discriminatory intent and unequal impact

Since inequalities can be caused either intentionally or unintentionally, the Supreme Court ruled that the Equal Protection Clause itself does not prohibit the government from pursuing policies that unintentionally create racial differences. Notwithstanding the fact that under other clauses of the constitution, Congress may have some power to combat unintended, unequal effects. This problem was addressed in the seminal Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp. (1977) discussed.

In this case, the plaintiff, a housing company, sued a city in the suburbs of Chicago that had refused to develop a property on which the plaintiff intended to build low-income, racially integrated housing. There was no clear evidence of racially discriminatory intent on the part of the Arlington Heights, Illinois Planning Commission . The result was racial , however , as the rejection allegedly prevented primarily African-Americans and Hispanics from moving in. Judge Lewis Powell , who wrote for the court, stated, "Proof of racially discriminatory intent or purpose is required to show a violation of the Equal Protection Clause." Unequal effects only have evidential value; in the absence of a "rigid" pattern, "impact [...] is not determinative." The result in "Arlington Heights" was similar to that in Washington v. Davis (1976) and was defended on the grounds that the Equal Protection Clause was not intended to guarantee equal outcomes , but rather equal opportunity ; if a legislature wants to correct unintended but racially disparate effects, it can do so through further legislation. It is possible for a discriminatory state to hide its true intent, and one possible solution is for different effects to be seen as stronger evidence of discriminatory intent. However, the debate is currently purely academic as the Supreme Court has not changed its basic approach as outlined in Arlington Heights .

An example of how this rule limits the powers of the Court of Justice under the Equal Protection Clause can be found in McClesky v. Kemp (1987). In this case, a black man was convicted of murdering a white police officer and sentenced to death in Georgia state. One study found that white killers were more likely to be sentenced to death than black killers. The court found that the defense had failed to demonstrate that such data demonstrated the required discriminatory intent of the Georgia legislature and executive.

Suffrage

The Supreme Court ruled in the Nixon v. Herndon (1927) that the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits refusal to vote on grounds of race . The first modern application of the Equal Protection Clause to the right to vote came in Baker v. Carr (1962), in which the Court ruled that the districts that sent representatives to the Tennessee state legislature were so misplaced (some MPs represented ten times as many residents as others) that they violated the Equal Protection Clause. It may seem counter-intuitive that the Equal Protection Clause should provide for equal voting rights ; after all, this appeared to obviate the need for the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution . Judge John M. Harlan (the grandson of former Judge Harlan) relies on this argument, as does the history of the Fourteenth Amendment legislation, in his dissent von Reynolds. Harlan cited the 1866 Congressional Debates to show that the authors did not intend to extend the Equal Protection Clause to include voting rights, and regarding the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendment, said:

If constitutional amendment was the only means by which all men and, later, women, could be guaranteed the right to vote at all, even for federal officers, how can it be that the far less obvious right to a particular kind of apportionment of state legislatures ... can be conferred by judicial construction of the Fourteenth Amendment? [Emphasis in the original.]

Harlan also relied on the fact that Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment "expressly recognizes the States' power to deny 'or in any way' abridge the right of their inhabitants to vote for 'the members of the [state] Legislature.'" Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment provides a specific federal response to such action by a state: reducing the representation of a state in Congress. The Supreme Court has instead held that the right to vote is a "fundamental right" on the same level as marriage ( Loving v. Virginia ); for any discrimination in fundamental rights to be constitutional, the court requires that legislation pass strict scrutiny . According to this theory, the jurisprudence on equal protection has been applied to the right to vote.

A new use of the equal protection doctrine came in Bush v. Gore (2000). It was about the controversial recount in Florida after the US presidential election in 2000 . There the Supreme Court ruled that the different standards of vote counting in Florida violated the equal protection clause . The Supreme Court used four of its decisions from the 1960s (one of which was Reynolds v. Sims ) to augment its judgment in the Bush v. Prop gore . This view was little controversial in the decision-making discussions, and within the court the proposal won the support of seven votes out of nine; Judges Souter and Breyer joined the majority of five - but only to determine that there was a violation of equal protection . The appeal chosen by the court, namely the suspension of a nationwide recount, was much more controversial.

Gender, disability and sexual orientation

Originally, the Fourteenth Amendment did not prohibit gender discrimination as much as other forms of discrimination. On the one hand, the second section of the constitutional amendment expressly prevented the states from interfering with the voting rights of "men", which made the amendment anathema to many women when it was passed in 1866. As feminists like Victoria Woodhull on the other hand pointed out, the word "person" in the Equal Protection Clause was apparently chosen deliberately instead of a masculine term.

In 1971 the US Supreme Court ruled Reed v. Reed , thereby expanding the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution to protect women from gender-based discrimination in situations where there is no rational basis for discrimination. This test measure was found in Craig v. Boren (1976) raised to intermediate scrutiny .

The Supreme Court has so far shown little inclination to extend the full suspect classification status (whereby a law categorized on this basis is subject to stronger judicial control) to groups other than racial minorities and religious groups. In City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, Inc. (1985), the court refused to make developmental disability a suspected classification . Judge Thurgood Marshall found in his partial concurrence, however, that the court examined the denial of approval for a group home for mentally disabled people by the city of Cleburne with a much higher level of control than would normally be associated with the rational basis test.

The judgment of the Court of Justice in the Romer v. Evans (1996) rejected a constitutional amendment in Colorado aimed at denying homosexuals "minority status, quota, protected status, or [a] right of discrimination". The court rejected the arguments of the minority vote as "implausible". This argues that the change would not deprive homosexuals of the general protection afforded to all others, but would merely prevent "special treatment of homosexuals". Similar to the City of Cleburne , the Romer decision appeared to require a significantly higher level of control than the nominally applied rational basis test.

In Lawrence v Texas (2003), on grounds of substantive due process , the court overturned a Texan law that outlawed homosexual sodomy . In the concurring opinion by Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, these argued that the Texas law by banning only "homosexual" sodomy and not "heterosexual" sodomy is not a review on rational basis under the Equal Protection Clause would stand; their vote quoted the City of Cleburne in a prominent place and was partly based on Romer. It is noteworthy that O'Connor's position did not pretend to use a level of scrutiny beyond rational basis , and the court did not extend suspect-class status to include sexual orientation .

After the courts conducted a rational review of classifications based on sexual orientation , it was argued that discrimination based on sex should be interpreted to include discrimination based on sexual orientation . In this case, intermediate scrutiny should apply to the rights of homosexuals. However, some authors disagree, arguing that "homophobia" is sociologically different from sexism and that it would therefore be an unacceptable legal shortcoming to treat it as such.

In 2013, the court overturned a part of the Federal Law for the Defense of Marriage ( Defense of Marriage Act ) in United States v. Windsor on. Since no federal law was in question, the Equal Protection Clause did not apply. However, the court applied similar principles, albeit in combination with principles of federalism. According to Erwin Chemerinsky, the court did not pretend to use a more stringent level of review than a rational basis review . The four dissenting judges argued that the drafters of the law were rational .

In 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 decision that the basic right to marry same-sex couples was guaranteed by both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, and required all states to be same-sex To permit couples to marry and to recognize same-sex marriages that have been effectively contracted in other jurisdictions.

Affirmative action (positive discrimination)

Affirmative action is the consideration of race, gender, or other factors in order to favor an underrepresented group or to redress past injustices inflicted on that group. People who belong to the group are treated against people who are not part of the group, e.g. B. in admission to training, recruitment, promotion, contracting and the like, preferred. Such an approach can be used as a tie-breaker when all other factors are not productive, or it can be achieved through racial quota , which assign a certain number of advantages to each group.

During the Reconstruction Era of the United States, Congress passed race-conscious programs primarily to aid newly released slaves who had been deprived of many personal benefits earlier in their lives. Such laws were passed by those who had also formulated the Equal Protection Clause , although this clause did not apply to federal law, but only to state law. Likewise, the Equal Protection Clause does not apply to private universities and other private companies that are free to take positive action, unless prohibited by federal or state law.

Several important affirmative action cases that were to come before the Supreme Court concerned government contractors such as Adarand Constructors v. Peña (1995) and City of Richmond v. JA Croson Co. (1989). But the most famous cases come from affirmative action on the part of public universities: Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), and two accompanying cases decided by the Supreme Court in 2003, Grutter v. Bollinger and Gratz v. Bollinger .

In Bakke , the court found that racial quota were unconstitutional, but that educational institutions can legally use race as one of many factors to consider in their university and college admissions process. In the Grutter and Gratz judgments , the court upheld both Bakke as a precedent and the University of Michigan Law School's admissions policy . In an obiter dictum , however, Judge O'Connor, who wrote for the court, said she expected that race preferences would no longer be necessary in 25 years . In Gratz , the court ruled Michigan's admission policy for undergraduates to be unconstitutional. It justified this by saying that in contrast to the admissions policy of the Law School, the race as one treated by many factors in a regulatory process that shuts off on each candidate, the procedure for undergraduates a scoring system used, the overly mechanistic was. In these affirmative-action cases, the Supreme Court used strict scrutiny , or at least claimed that it used strict scrutiny , as plaintiffs challenged affirmative-action over categorization by race . The Grutter admissions policy and the Harvard College admissions policy , praised by Judge Powell's Bakke statement , met these requirements because the court ruled that they were narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling interest in diversity . On the one hand, critics have argued - including Judge Clarence Thomas in his dissent with Grutter - that the test the court used in some cases is much less stringent than a true strict scrutiny, and that the court has not principally applied the law but biased politically. On the other hand, it is argued that the purpose of the Equal Protection Clause is to prevent the socio-political subordination of some groups to others, and not to prevent classification; because it does so, non-invasive classifications such as those used by positive action programs should not be scaled up.

Web links

- Original Meaning of Equal Protection of the Laws , Federalist Blog

- Equal Protection: An Overview , Cornell Law School

- Equal Protection , Heritage Guide to the Constitution

- Equal Protection (US law) , Encyclopædia Britannica

- Naderi, Siavash. " The Not So Definite Article ", Brown Political Review (November 16, 2012).

Individual evidence

- ↑ http://www.verfassungen.net/us/verf87-i.htm

- ↑ Antieau, Chester James: Equal Protection Clause outside the . In: California Law Review . tape 40 , no. 3 , 1952, pp. 362-377 , doi : 10.2307 / 3477928 , JSTOR : 3477928 ( online ).

- ↑ a b Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 US 393 (1856) (en) . In: Justia Law .

- ^ Dred Scott, 150 Years Ago . In: The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education . No. 55 , 2007, p. 19 , JSTOR : 25073625 .

- ^ Swisher, Carl Brent: Dred Scott One Hundred Years After . In: The Journal of Politics . tape 19 , no. 2 , 1957, p. 167-183 , doi : 10.2307 / 2127194 , JSTOR : 2127194 .

- ↑ For details on the establishment and adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, see generally Eric Foner: Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 . Harper & Row, New York 1988, ISBN 978-0-06-091453-0 . , and Paul Brest et al: Processes of Constitutional Decisionmaking . Aspen Law & Business, Gaithersburg 2000, ISBN 978-0-7355-1250-4 , pp. 241-242 .

- ↑ See Brest et al. (2000), pp. 242-46.

- ↑ Rosen, Jeffrey. The Supreme Court: The Personalities and Rivalries That Defined America , p. 79 (MacMillan 2007).

- ↑ Newman, Roger. The Constitution and its Amendments , Vol. 4, p. 8 (Macmillan 1999).

- ↑ Hardy, David. "Original Popular Understanding of the 14th Amendment As Reflected in the Print Media of 1866-68," Whittier Law Review, Vol. 30, pp. 695 (2008-2009).

- ↑ See Foner (1988), passim. See also Bruce A. Ackerman: We the People, Volume 2: Transformations . Belknap Press, Cambridge 2000, ISBN 978-0-674-00397-2 , pp. 99-252 .

- ^ A b Zuckert, Michael P .: Completing the Constitution: The Fourteenth Amendment and Constitutional Rights . In: Publius . tape 22 , no. 2 , 1992, p. 69-91 , doi : 10.2307 / 3330348 , JSTOR : 3330348 .

- ↑ a b Coleman v. Miller, 307 U.S. 433 (1939) (en) . In: Justia Law .

- ↑ a b c Perry, Michael J .: Modern Equal Protection: A Conceptualization and Appraisal . In: Columbia Law Review . tape 79 , no. 6 , 1979, pp. 1023-1084 , doi : 10.2307 / 1121988 , JSTOR : 1121988 .

- ^ A b Boyd, William M .: The Second Emancipation . In: Phylon . tape 16 , no. 1 , 1955, pp. 77-86 , doi : 10.2307 / 272626 , JSTOR : 272626 .

- ^ Sumner, Charles, and Daniel Murray Pamphlet Collection. . Washington: S. & RO Polkinhorn, Printers, 1874. PDF. https://www.loc.gov/item/12005313/.

- ↑ Frank, John P .; Munro, Robert F .: The Original Understanding of "Equal Protection of the Laws" . In: Columbia Law Review . tape 50 , no. 2 , 1950, p. 131-169 , doi : 10.2307 / 1118709 , JSTOR : 1118709 ( online ).

- ^ George W. Baltzell: Constitution of the United States - We the People. In: constitutionus.com. Retrieved November 10, 2018 (American English).

- ^ Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 US 36 (1872) (en) . In: Justia Law .

- ↑ a b Kelly, Alfred. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: Clio and the Court: An Illicit Love Affair ) ", The Supreme Court Review at p. 148 (1965) reprinted in The Supreme Court in and of the Stream of Power (Kermit Hall ed. , Psychology Press 2000).

- ↑ Bickel, Alexander . " The Original Understanding and the Segregation Decision, " Harvard Law Review , Vol. 69, pp. 35-37 (1955). Bingham spoke on February 27, 1866. See transcript .

- ^ Curtis, Michael. " Resurrecting the Privileges or Immunities Clause and Revising the Slaughter-House Cases Without Exhuming Lochner: Individual Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment ", Boston College Law Review , Vol. 38 (1997).

- ↑ Glidden, William. Congress and the Fourteenth Amendment: Enforcing Liberty and Equality in the States , p. 79 (Lexington Books 2013).

- ↑ Steve Mount: Ratification of Constitutional Amendments. January 2007, accessed February 24, 2007 .

- ↑ Flack, Horace. The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment , p. 232 (Johns Hopkins Press, 1908). For Bingham's full speech, see Appendix to the Congressional Globe, 42d Congress, 1st Sess. , p. 83 (March 31, 1871).

- ↑ requires citation

- ↑ Wallenstein, Peter. Tell the Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage, and Law - An American History , p. 253 (Palgrave Macmillan, Jan 17, 2004). The four of the original thirteen states are New Hampshire, Connecticut, New Jersey and New York. Id.

- ↑ Pascoe, Peggy. What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America , p. 58 (Oxford U. Press 2009).

- ↑ Calabresi, Steven and Matthews, Andrea. "Originalism and Loving v. Virginia", Brigham Young University Law Review (2012).

- ↑ Foner, Eric . Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 , pp. 321-322 (HarperCollins 2002).

- ↑ Bickel, Alexander . " The Original Understanding and the Segregation Decision, " Harvard Law Review , Vol. 69, pp. 35-37 (1955).

- ^ Finkelman, Paul. " Rehearsal for Reconstruction: Antebellum Origins of the Fourteenth Amendment, " in The Facts of Reconstruction: Essays in Honor of John Hope Franklin , p. 19 (Eric Anderson and Alfred A. Moss, eds., LSU Press, 1991).

- ↑ Woloch, Nancy. Women and the American Experience , p. 185 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984).

- ↑ Wayne, Stephen. Is This Any Way to Run a Democratic Election? , p. 27 (CQ PRESS 2013).

- ↑ McInerney, Daniel. A Traveller's History of the USA , p. 212 (Interlink Books, 2001).

- ↑ Kerber, Linda. No Constitutional Right to Be Ladies: Women and the Obligations of Citizenship , p. 133 (Macmillan, 1999).

- ↑ Yick Wo v. Hopkins , 118 U.S. 356 (1886).

- ↑ Annotation 18 - Fourteenth Amendment: Section 1 - Rights Guaranteed: Equal Protection of the Laws: Scope and application state action . FindLaw for Legal Professionals - Law & Legal Information by FindLaw, a Thomson Reuters business. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ For a summary of Plessy's social, political, and historical background , see C. Vann Woodward: The Strange Career of Jim Crow . Oxford University Press, New York 2001, ISBN 978-0-19-514690-5 , pp. 6, 69-70 .

- ↑ For a critical evaluation of Harlan see Chin, Gabriel J .: The Plessy Myth: Justice Harlan and the Chinese Cases . In: Iowa Law Review . tape 82 , 1996, ISSN 0021-0552 , pp. 151 .

- ↑ See Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad , 118 US 394 (1886). In the summary of the case, Bancroft wrote that the court stated that it did not need to hear arguments about whether the Equal Protection Clause protects companies because "we are all of the opinion that it does." Id. At 396. Chief Justice Morrison Waite announced in the Chamber that the Court would not hear arguments on the question of whether the corporate equality clause applies: "We are all of the opinion that it does." The background and developments from this statement are given in H. Graham, Everyman's Constitution - Historical Essays on the Fourteenth Amendment, the Conspiracy Theory, and American Constitutionalism (1968), chs. 9, 10, and pp. 566-84 treated. Judge Hugo Black , at Connecticut General Life Ins. Co. v. Johnson, 303 US 77, 85 (1938), and Judge William O. Douglas , in Wheeling Steel Corp. v. Glander, 337 US 562, 576 (1949) disagree that corporations constitute persons for purposes of equal protection.

- ↑ See Providence Bank v. Billings , 29 US 514 (1830), in which Chief Justice Marshall wrote: "The great object of an incorporation is to bestow the character and properties of individuality on a collective and changing body of men." Nevertheless, the concept of corporate personhood remains controversial. See Mayer, Carl J .: Personalizing the Impersonal: Corporations and the Bill of Rights . In: Hastings Law Journal . tape 41 , 1990, ISSN 0017-8322 , pp. 577 ( online ).

- ↑ See Currie, David P .: The Constitution in the Supreme Court: The New Deal, 1931-1940 . In: University of Chicago Law Review . tape 54 , no. 2 , 1987, pp. 504-555 , doi : 10.2307 / 1599798 , JSTOR : 1599798 ( online ).

- ↑ Feldman, Noah. Scorpions: The Battles and Triumphs of FDR's Great Supreme Court Justices , p. 145 (Hachette Digital 2010).

- ↑ See generally Aldon D. Morris: Origin of the Civil Rights Movements: Black Communities Organizing for Change . Free Press, New York 1986, ISBN 978-0-02-922130-3 .

- ↑ Karlan, Pamela S .: WHAT CAN BROWN DO FOR YOU ?: NEUTRAL PRINCIPLES AND THE STRUGGLE OVER THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE . In: Duke Law Journal . tape 58 , no. 6 , 2009, p. 1049-1069 , JSTOR : 20684748 .

- ↑ For a detailed history of the Brown case from start to finish, see Richard Kluger: Simple Justice . Vintage, New York 1977, ISBN 978-0-394-72255-9 ( online ).

- ↑ Shimsky, Mary Jane. "Hesitating Between Two Worlds": The Civil Rights Odyssey of Robert H. Jackson , p. 468 (ProQuest, 2007).

- ^ I Dissent: Great Opposing Opinions in Landmark Supreme Court Cases , pp. 133-151 (Mark Tushnet, ed. Beacon Press, 2008).

- ↑ For a comprehensive history of school segregation from Brown to Milliken , see Brest et al. (2000), pp. 768-794.

- ↑ For the history of American politics' engagement with the Supreme Court's obligation to desegregate (and vice versa), see Lucas A. Powe, Jr .: The Warren Court and American Politics . Belknap Press, Cambridge, MA 2001, ISBN 978-0-674-00683-6 . , and Nick Kotz: Judgment Days: Lyndon Baines Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Laws That Changed America . Houghton Mifflin, Boston 2004, ISBN 978-0-618-08825-6 ( online ). More on the debate summarized in the text can be found e.g. B. in Gerald N. Rosenberg: The Hollow Hope: Can Courts Bring About Social Change? University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1993, ISBN 978-0-226-72703-5 . , and Klarman, Michael J .: Brown , Racial Change, and the Civil Rights Movement . In: Virginia Law Review . tape 80 , no. 1 , 1994, p. 7-150 , doi : 10.2307 / 1073592 , JSTOR : 1073592 .

- ↑ Reynolds, Troy. "Education Finance Reform Litigation and Separation of Powers: Kentucky Makes Its Contribution," Kentucky Law Journal , Vol. 80 (1991): 309, 310.

- ↑ Minow, Martha . "Confronting the Seduction of Choice: Law, Education and American Pluralism," Yale Law Journal , Vol. 120, p. 814, 819-820 (2011) ( Pierce "entrenched the pattern of a two-tiered system of schooling, which sanctions private opt-outs from publicly run schools").

- ↑ For data and analysis see Orfield: Schools More Separate. (No longer available online.) In: Harvard University Civil Rights Project. July 2001, archived from the original on June 28, 2007 ; Retrieved July 16, 2008 .

- ^ Jacobs, Nicholas: Racial, Economic, and Linguistic Segregation: Analyzing Market Supports in the District of Columbia's Public Charter Schools. In: Education and Urban Society . tape 45 , no. 1 , August 8, 2011, p. 120-141 , doi : 10.1177 / 0013124511407317 ( online [accessed October 28, 2013]).

- ↑ FindLaw | Cases and Codes. In: Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. May 17, 1954, accessed August 13, 2012 .

- ↑ Lawrence v. Texas, 539 US 598 (2003), p. 2482

- ↑ Balkin, JM; Bruce A. Ackerman (2001). "Part II". What Brown v. Board of Education should have said: the nation's top legal experts rewrite America's landmark civil rights decision. et al. New York University Press. P. 168.

- ↑ 304 US 144, 152 n.4 (1938). For a theory of judicial review based on Stone's footnote, see Ely, John Hart (1981). Democracy and Distrust . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-19637-6 .

- ↑ Goldstein, Leslie. " Between the Tiers: The New (est) Equal Protection and Bush v. Gore, " University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law , Vol. 4, p. 372 (2002).

- ↑ Farber, Daniel and Frickey, Philip. " Is Carolene Products Dead - Reflections on Affirmative Action and the Dynamics of Civil Rights Legislation, " California Law Review , Vol. 79, p. 685 (1991). Farber and Frickey point out that "only Chief Justice Hughes, Justice Brandeis, and Justice Roberts joined Justice Stone's footnote", and in any case: "It is simply a myth ... that the process theory of footnote four in Carolene Products is, or ever has been, the primary justification for invalidating laws embodying prejudice against racial minorities. "

- ↑ Skinner v. Oklahoma , 316 US 535 (1942). Sometimes the " suspect classification " approach of modern doctrine is applied to Korematsu v. United States returned (1944). Korematsu , however, did not concern the Fourteenth Amendment and arose later than the Skinner Decision (which clearly stated that both the deprivation of fundamental rights and the oppression of a particular race or nationality were in question).

- ↑ See United States v. Virginia (1996).

- ↑ a b Fleming, James. " There is Only One Equal Protection Clause: An Appreciation of Justice Stevens's Equal Protection Jurisprudence ", Fordham Law Review , Vol. 74, p. 2301, 2306 (2006).

- ↑ See Romer v. Evans , 517 US 620, 631 (1996): "the equal protection of the laws must coexist with the practical necessity that most legislation classifies for one purpose or another, with the resulting disadvantage to various groups or persons."

- ↑ Curry, James et al. Constitutional Government: The American Experience , p. 282 (Kendall Hunt 2003) (attributing the phrase to Gerald Gunther).

- ↑ Domino, John. Civil Rights & Liberties in the 21st Century , pp. 337-338 (Pearson 2009).

- ^ Don Herzog: Constitutional Rights: Two . In: Left2Right . It should be noted that the Court of Justice has placed significant limits on the congressional power of enforcement . See City of Boerne v. Flores (1997), Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama v. Garrett (2001), and United States v. Morrison (2000). The Court has also interpreted federal law as restricting states' powers to correct unequal effects. See Ricci v. DeStefano (2009).

- ↑ See Linda Hamilton Krieger: The Content of Our Categories: A Cognitive Bias Approach to Discrimination and Equal Protection Opportunity . In: Stanford Law Review . tape 47 , no. 6 , 1995, pp. 1161-1248 , doi : 10.2307 / 1229191 , JSTOR : 1229191 . , and Lawrence, Charles R., III: Reckoning with Unconscious Racism . In: Stanford Law Review . tape 39 , no. 2 , 1987, pp. 317-388 , doi : 10.2307 / 1228797 , JSTOR : 1228797 .

- ↑ Baldus, David C .; Pulaski, Charles; Woodworth, George: Comparative Review of Death Sentences: An Empirical Study of the Georgia Experience . In: Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology . tape 74 , no. 3 , 1983, p. 661-753 , doi : 10.2307 / 1143133 , JSTOR : 1143133 ( online ).

- ^ Van Alstyne, William. "The Fourteenth Amendment, the Right to Vote, and the Understanding of the Thirty-Ninth Congress," Supreme Court Review , p. 33 (1965).

- ↑ For the criticism and several justifications of the decision of the court, see Bush v. Gore : The Question of Legitimacy , edited by Bruce A. Ackerman: Bush v. Gore: the question of legitimacy . Yale University Press, New Haven 2002, ISBN 978-0-300-09379-7 . Another much-cited collection of articles is Cass Sunstein, Richard Allen Epstein: The Vote: Bush, Gore, and the Supreme Court . Chicago University Press, Chicago 2001, ISBN 978-0-226-21307-1 .

- ↑ Cullen-Dupont, Kathryn. Encyclopedia of Women's History in America , pp. 91-92 (Infobase Publishing, Jan 1, 2009).

- ↑ Hymowitz, Carol and Weissman, Michaele. A History of Women in America , p. 128 (Random House Digital, 2011).

- ^ " Reed v. Reed - Significance, Notable Trials and Court Cases - 1963 to 1972"

- ↑ Craig v. Boren , 429 U.S. 190 (1976).

- ↑ See Pettinga, Gayle Lynn: Rational Basis with Bite: Intermediate Scrutiny by Any Other Name . In: Indiana Law Journal . tape 62 , 1987, ISSN 0019-6665 , pp. 779 . ; Wadhwani, Neelum J .: Rational Reviews, Irrational Results . In: Texas Law Review . tape 84 , 2006, ISSN 0040-4411 , p. 801, 809-811 .

- ↑ Kuligowski, Monte. "Romer v. Evans: Judicial Judgment or Emotive Utterance ?," Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development , Vol. 12 (1996).

- ^ Joslin, Courtney: Equal Protection and Anti-Gay Legislation . In: Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review . tape 32 , 1997, ISSN 0017-8039 , pp. 225, 240 : "The Romer Court applied a more 'active,' Cleburne -like rational basis standard ..." ; Farrell, Robert C .: Successful Rational Basis Claims in the Supreme Court from the 1971 Term Through Romer v. Evans . In: Indiana Law Review . tape 32 , 1999, ISSN 0019-6665 , p. 357 .

- ^ See Koppelman, Andrew: Why Discrimination against Lesbians and Gay Men is Sex Discrimination . In: New York University Law Review . tape 69 , 1994, ISSN 0028-7881 , pp. 197 . ; see also Fricke v. Lynch , 491 F.Supp. 381, 388, fn. 6 (1980), vacated 627 F.2d 1088 [case decided on First Amendment free-speech grounds, but "This case can also be profitably analyzed under the Equal Protection Clause of the fourteenth amendment. In preventing Aaron Fricke from attending the senior reception , the school has afforded disparate treatment to a certain class of students those wishing to attend the reception with companions of the same sex. "]

- ↑ Gerstmann, Evan. Same Sex Marriage and the Constitution , p. 55 (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

- ↑ United States v. Windsor , No. 12-307, 2013 BL 169620, 118 FEP Cases 1417 (US June 26, 2013).

- ^ Affirmative Action . Stanford University. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- ↑ See Schnapper, Eric: Affirmative Action and the Legislative History of the Fourteenth Amendment . In: Virginia Law Review . tape 71 , no. 5 , 1985, pp. 753-798 , doi : 10.2307 / 1073012 , JSTOR : 1073012 ( online [PDF]).

- ↑ See Peter H. Schuck: Reflections on Grutter . (No longer available online.) In: Jurist. September 5, 2003, archived from the original on September 9, 2005 ; accessed on June 24, 2020 .

- ^ See Siegel, Reva B .: Equality Talk: Antisubordination and Anticlassification Values in Constitutional Struggles over Brown . In: Harvard Law Review . tape 117 , no. 5 , 2004, p. 1470-1547 , doi : 10.2307 / 4093259 , JSTOR : 4093259 ( online ). ; Stephen L. Carter: When Victims Happen to Be Black . In: Yale Law Journal . tape 97 , no. 3 , 1988, pp. 420-447 , doi : 10.2307 / 796412 , JSTOR : 796412 ( online ).