John Marshall Harlan

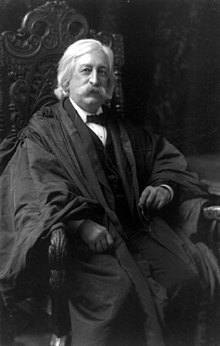

John Marshall Harlan (* 1. June 1833 in Boyle County , Kentucky ; † 14. October 1911 in Washington, DC ) was an American lawyer and from 1877 until his death judge at the Supreme Court of the United States . He was appointed to succeed David Davis as the 44th judge in the history of the court and was one of the first constitutional judges in the United States to obtain a law degree. In contrast to most of his predecessors and colleagues, his legal education was not based, as was customary at the time, on a mere apprenticeship in a law firm.

He was best known through the controversial decision of the Court of Justice in May 1896 in the Plessy v. Ferguson , with whom the Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation legislation in the southern states was constitutional. Harlan, himself a former slave owner, was the only judge to reject the 7-to-1 ruling. In his minority opinion , he predicted that the judgment would go down in court history as a shame. The principle of " Separate but equal " based on the judgment , which defined the legal and social basis for racial segregation in the following decades, was adopted in 1954 by the decision of Brown v. Board of Education repealed.

Harlan's 34-year tenure is one of the longest in Supreme Court history. It was characteristic of his work as a judge that he took a different position than the majority of his colleagues in around a quarter of the statements made in the judgments. He is one of a number of judges in the history of the court who are called great dissenter due to their opinion, which often differs from the majority of judges , and is considered one of the most outstanding constitutional judges in the history of the United States.

Life

Family and education

John Marshall Harlan was born on June 1, 1833 into a family of the so-called planter aristocracy. Her ancestors had arrived in Delaware as Quakers in 1687 . The Harlans owned extensive estates and around half a dozen slaves for household chores and maintenance of the surrounding gardens. A number of family members had held influential positions in the politics of the colonies and later US states throughout the family's history. His father, James Harlan, was a lawyer and a member of the United States Congress for two terms . He later worked in Kentucky as a politician in various offices, including as Attorney General . His mother, Eliza Shannon Davenport, came from a local farming family. In 1822 his parents married. They named their sixth of nine children after John Marshall , a prominent former presiding judge on the Supreme Court.

Harlan first attended a private academy in Frankfort , Kentucky, as there were no state schools in his home state at the time. He then studied until 1850 at Center College in Danville . On the side, he worked on legal literature in his father's legal practice. He received his law degree from Transylvania University in Lexington in 1852. At the time, a university education was not a requirement for a job as a lawyer or judge, as the law schools referred to as law schools were just emerging. Rather, the training of lawyers usually took place through an apprenticeship in the office of a practicing lawyer. Harlan was admitted to the bar a year after graduating. From 1854 to 1856 he worked as a lawyer in his father's practice in Frankfort. In 1856 he married Malvina French Shanklin, together they had three sons and three daughters.

Professional and political career

Like his father, he was initially a member of the Whig Party . The Whigs' views of a strong central government also shaped his later legal positions. After the dissolution of the party, he was active in several other parties, including the Know-nothings . Despite these multiple changes, his position on slavery at the time was clear: he supported it unreservedly and saw a possible abolition as a violation of private property rights. In 1858 he was elected a judge in Franklin County , Kentucky , and served in that office until 1861. In 1859 he ran for a seat in the United States House of Representatives , but narrowly lost the election. Two years later he moved to Louisville and started a law practice there with a partner.

With the onset of the civil war in 1861 he volunteered to serve in the army of the Union , and rose during the war to the brevet of colonel on. On the one hand, he continued to support slavery unreservedly , but through his service to the north he was primarily committed to preserving the Union. In the conflict between these two positions, there were probably two main reasons for his support for the northern states. On the one hand, he saw the preservation of the Union in its existing form as essential for the future of his home state Kentucky and that of the other states. On the other hand, at least at the beginning of the war, he assumed that slavery would continue to exist after the war. He had initially announced his retirement in the event that President Abraham Lincoln signed the Declaration on the Abolition of Slavery . After the announcement of the proclamation in September 1863, however, he initially remained in the service, although he described the declaration as "unconstitutional and null and void". He did not leave the army to take care of his family until several months later, after his father died. For a short time he took over his father's office in Frankfort.

In the following years he devoted himself to his career again and was from 1863 to 1867 Attorney General of the State of Kentucky. In 1866, in this capacity, he brought an indictment of violation of the Kentucky Slave Code against John M. Palmer , who, as a general of the Northern States troops, had recruited male slaves to enable them and their families to go free. After the end of his tenure, he moved back to Louisville to practice as a lawyer. From 1870 onwards, his friend Benjamin H. Bristow , who probably had a great influence on Harlan's later rejection of slavery, was his partner in the law firm for a short time. After the entry into force of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution , which officially abolished slavery in 1865, he released the slaves in his own household into freedom in December 1865. Nonetheless, he continued to reject the 13th Amendment to the Constitution and the abolition of slavery.

After the influence and importance of the Whigs had declined significantly from around 1860 and Harlan had lost his re-election as Kentucky Attorney General in 1867, he was faced with a decision between the Democrats and the Republicans for his further political career . Since the Democrats at that time, contrary to Harlan's own views, demanded a strengthening of the powers of the individual states, he joined the Republican Party in 1868 and remained a member until his death. In accordance with the attitude of his party, he became a bitter opponent of slavery in the following years and in 1871 called it the "highest form of arbitrary rule that ever existed on this earth", the Ku Klux Klan he called the "enemy of all order". He commented on the fundamental change in his views with the words

"Let it be said that I am right rather than consistent."

"I'd rather be on the right side than consistent."

In 1871 and 1875 he ran for his party as governor of his home state, but lost the election in both cases.

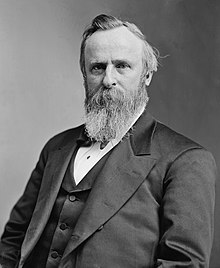

Appointment to the Supreme Court Judge

On November 29, 1877 he was confirmed by the Senate to succeed David Davis as Supreme Court Justice and sworn in on December 10 of the same year. Davis had previously resigned from his judicial office due to his election to the Senate. In the presidential election in the Republican Party a year earlier, Harlan initially supported the nomination of his friend Benjamin Bristow, a representative of the party's reform wing. When Bristow could not prevail in the first four ballots, Harlan convinced almost all of Bristow's supporters among the delegates to vote for Rutherford B. Hayes . This then won the primaries in the seventh ballot with a result of 384 to 351 votes against his competitor James G. Blaine from the moderate wing. In addition to the votes of Bristow's supporters, the supporters of Oliver Morton , a senator from the important state of Indiana and radical supporter of the reintegration of the southern states into the Union, known as Reconstruction , were also decisive in the election. In return for the election of Hayes they were offered a high legal office for Harlan.

When Hayes, who was elected president a short time later, had to fill a judge's post at the Supreme Court in the spring of 1877, Bristow was already too controversial in his own party to be nominated. Hayes then recalled the merits of Harlan in his own election as well as the agreement with Morton's supporters a year earlier. In addition, Harlan came from the southern United States and was thus considered a suitable candidate to please the southern wing of both Republicans and Democrats . Hayes was also interested in maintaining his own reputation as a reformer within the Republican Party. All of this led him to propose Harlan as a candidate for office on October 16, 1877. Initial doubts in the Senate focused on several issues. On the one hand, there was resistance from some senators who feared an over-representation of the judicial district, which was already represented by two judges and to which Kentucky belonged. A number of Republican senators, regardless of Harlan's identity, also saw an opportunity to inflict defeat on President Hayes. There were also doubts about the motivation and sincerity of his change of heart regarding slavery and his early withdrawal from the Northern Army during the Civil War. Harlan responded to these criticisms in several letters to the Senate and was finally confirmed in a joint vote on a total of 17 candidates who were nominated for various offices.

During his tenure, he saw three different presiding judges on the Supreme Court. From 1874 to 1888, Morrison Remick Waite presided over the court. Contrary to Harlan's views, Waite was generally in favor of restricting the powers of the federal government, especially in decisions on amendments to the constitution from the time of the Reconstruction. Melville Weston Fuller served as presiding judge from 1888 to 1910 . Under his leadership, the tendency towards the de facto withdrawal of the legal regulations on equality and equality, which had begun with the end of the Reconstruction, continued. The final year of Harlan's tenure falls during the time of the court under the leadership of Edward Douglass White , presiding judge from 1910 to 1921. Like Harlan, White was a former slave owner, but unlike Harlan, he served in the Army during the Civil War committed to the southern states.

In addition to his work as a judge at the Supreme Court, Harlan taught constitutional law at an evening law school, which later became part of George Washington University , at whose law school he was also active as a professor from 1889.

Harlan's choices in various areas

Harlan's decisions in the relevant legal subject areas of his time cannot be assigned to any particular political or legal philosophy. He regarded the Supreme Court as the guardian of the constitution and revered James Madison , US President from 1809 to 1817, and former presiding judge John Marshall , whose decisions were authoritative for him. He attached great importance to the concept of stare decisis , the strict binding of the court to previous judgments. With regard to his constitutional views, he was considered a federalist as well as a strict constructionist , i.e. as a representative of a narrow and verbatim interpretation of the constitution, and made a name for himself above all for opinions that differed from the court majority. Although he was generally on good terms with fellow judges, he showed little interest in compromising judgment when a case touched his moral or political beliefs.

In one of his first decisions after his appeal to the court, Strauder v. West Virginia in 1880, it was about black equality. Harlan voted on this with the majority of the court, which, on the basis of the principle of equal treatment, declared a law of the state of West Virginia to be unconstitutional that bar blacks from an appeal to a jury in court cases. In the years after the end of the Reconstruction, however, the Supreme Court increasingly refrained from interpreting constitutional amendments 13 (1865), 14 (1868) and 15 (1870) in favor of the protection of the Afro-American minority on civil rights issues. Harlan opposed these decisions and wrote several eloquent minority opinions, in which he advocated equality and equality of the different population groups.

When the Supreme Court finally abolished the Civil Rights Act of 1875 in a joint decision on five civil rights cases in 1883 , Harlan was again the only dissent. He argued, among other things, that discrimination against blacks is a hallmark of slavery and that Congress should legally prohibit this discrimination, including for private individuals. He referred to passages in the 13th and 14th Amendment to the Constitution. In addition, he accused the majority of the courts in particular to undermine the constitutional amendments from the time of the Reconstruction. Even in his later years he usually voted against the majority of the court in such cases, for example in the 1908 decision of Berea College v. Commonwealth of Kentucky . In the ruling on the case, the Supreme Court ruled that Kentucky was constitutional to law that explicitly prohibited private schools and colleges from teaching white and black students or students in mixed classes.

While his decisions on civil rights cases and equality issues have generally been consistent, there are a few exceptions worth mentioning. In the unanimous decision on the Pace v. For example, Alabama in 1883 voted along with the court majority. He rejected the argument that a law in Alabama that punished extramarital sex between whites and blacks more severely than in non-mixed relationships would violate the 14th Amendment. In Cumming v. Richmond County's Board of Education in 1899, he drafted the majority opinion. That decision legalized a tax levied in Richmond County, Alabama, which was used solely to fund schools for white children. Although the court primarily put forward economic reasons for this decision and refused to have jurisdiction on the basis of constitutional principles, this case represented a de facto legalization of racial segregation in public schools.

In cases in the areas of tax law and labor and business law , other central issues of this period in the history of the United States, he ruled in favor of taxpayers and employees as well as of large companies. His reputation as a “judge of ordinary people”, which is sometimes attributed to him, therefore only partially corresponds to the actual profile of his decisions. In the case of Pollock v. In 1895, Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. , whose issue was the federal income tax base, disagreed with the court majority, whose decision was viewed by most Americans as a unilateral favor of large companies. The United States v. He was the only judge to reject EC Knight Co. , which in the same year led to a restriction of the federal government's ability to act against economic monopolies. In the case of Lochner v. New York in 1905, he contradicted the decision of the court majority, which ruled inadmissible a New York state law that restricted the working hours of workers in bakeries for health reasons. On the other hand, in 1908 he wrote the majority opinion in the Adair v. United States , where the court ruled unconstitutional a federal law prohibiting companies from firing workers solely on the basis of union membership . The majority of the judges saw in this law an inadmissible restriction of the freedom rights of employees and employers.

Harlan was in the context of the decision Hurtado v. California, in 1884, became the first judge to rule that the 14th Amendment included the Bill of Rights . According to this view, there is an obligation for the states to grant the fundamental rights formulated in the Bill of Rights to all people under their jurisdiction. This legal conception only prevailed in a series of rulings by the Supreme Court in the 1940s and 1950s. In today's jurisprudence, almost all civil rights formulated in the Bill of Rights and the constitutional amendments from the time of the civil war are subject to the 14th constitutional amendment, even if from a legal theoretical point of view not on the basis of Harlan's argumentation.

Plessy v. Ferguson

In May 1896, the Supreme Court ruled the Plessy v. Ferguson made one of the most controversial decisions in history. The subject of the case was the constitutionality of a law of the state of Louisiana that required separation between blacks and whites in different compartments on railroad trains. With the decision of the court, not only this special law, but also racial segregation in the southern states in general was declared constitutional and thus the doctrine of “ Separate but equal ” was established. The majority of the Court, led by Judge Henry Billings Brown , ruled that the separate provision of facilities for blacks and whites would not constitute inequality and that any resulting feeling of inferiority for blacks would not reflect social and societal realities.

Harlan was again the only deviator in this 7-to-1 decision. In his minority opinion, which served as an inspiration to civil rights activists of the following generations, he stated, among other things:

“[...] The white race sees itself as the dominant race in this country. And it is in terms of prestige, achievement, education, wealth, and power. I have no doubt that it will be forever if it remains true to its great heritage and adheres to the principles of constitutional freedoms. But from the point of view of this Constitution and before the eyes of the law, there is no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens in this country. There are no boxes here. Our constitution is blind to skin color, it neither knows nor tolerates classes between citizens. In terms of civil rights, all people are equal before the law. The weakest is equal to the strongest. The law sees people as human beings and does not consider their environment or skin color when it comes to their rights guaranteed by the highest law of this country. It is therefore regrettable that this High Court, the highest instance of the constitution of this country, has come to the conclusion that a federal state can regulate the use of civil rights by its citizens on the basis of race alone.

[…]

60 million whites are in no way endangered by the presence of eight million blacks. The destinies of the two races in this country are inextricably linked, and the interests of both call for a common government for all that does not allow the seeds of racial hatred to be planted with the approval of the law.

[...]

There is a race so different from our own that we are not allowing its members to become citizens of the United States. People belonging to this race are, with a few exceptions, completely excluded from this society. I mean the Chinese breed. But under the law in question, a Chinese can ride in the same compartment as a white citizen of the United States while black races citizens of Louisiana, many of whom have certainly risked their lives to maintain the Union, and who are entitled by law are to participate in the political life of the state and the nation, and who are not excluded by law or because of their race from any kind of public place, and who legally have all the rights that white citizens have, are declared criminals who are imprisoned can when they travel in a public railroad car manned by white-race citizens. [...] "

Harlan further argued that this law was a " badge of servitude " and would demean black people. He predicted that in the future the court's ruling would be viewed as a shame similar to that of Dred Scott v. Sandford :

"In my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott Case."

This judgment manifested slavery in 1857 and shifted the legal view to the benefit of the slave owners. The “Separate but equal” doctrine was finally adopted in 1954, 58 years after Plessy v. Ferguson , with the judgment in the Brown v. Board of Education repealed. The decision of Cumming v. Richmond County's Board of Education was thereby repealed.

Harlan's Plessy vote in the context of further decisions

Harlan's opinion in Plessy v. Ferguson made it clear on the one hand that he strictly took the view that the law would not allow racial segregation and that all people were fundamentally equal. Nonetheless, on the other hand, he attached great importance to the cultural identity of the white and black “races” and their maintenance, which is also reflected in some of his statements in Plessy v. Ferguson expressed:

“[...] Every real man has pride in his race, and under the appropriate conditions, when the rights of others, those of his equals before the law, are not affected, it is his privilege to express that pride and to exercise it on that basis act as he sees fit. [...] "

For him, equality and equality between whites and blacks was more a legal question, the answer of which he sought in the constitution, than a personal conviction. Although he did not reject a “mixing” between whites and blacks in unions and social activities, he was also not as open-minded towards it as most of his minority opinions might suggest. In this sense, in addition to his remarks on the superiority of the white "race" in Plessy v. Ferguson, for example, also made his decisions in Pace v. Alabama and Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education understand.

The same applies to his statements in Plessy v. Ferguson on the position of the Chinese in American society, which, together with his decision in the United States v. Wong Kim Ark and several other cases on the legal situation of Chinese immigrants in the United States probably also resulted from the belief in the social and societal superiority of the white "race". In United States v. Wong Kim Ark he had voted against the court majority in 1898 together with Melville Fuller. In a 6-to-2 decision in the case of Wong Kim Ark, who was born in San Francisco as the son of Chinese immigrants, the latter had ruled that the descendants of foreigners who were legally resident in the United States at the time the child was born are entitled to have American citizenship. Harlan supported Fuller's opinion, in which he rejected the interpretation of the 14th Amendment on which the decision was based. Fuller argued that American citizenship law no longer followed the territorial principle resulting from the tradition of English law , but rather that the principle of descent had prevailed in United States jurisprudence . Part of the rationale was strong cultural differences that Fuller and Harlan believed would prevent full assimilation of Chinese-born immigrants into American society.

Death and successor

Harlan had a robust physical constitution well into old age and was active in sports for many years in his spare time. It is said that at the age of 75, he took part in a baseball game between judges and lawyers. In addition, he is considered to be the first judge in the history of the court to be passionate about golf whenever and wherever the opportunity arose. During the session of the court, he was active almost every day at the Chevy Chase Club in Bethesda, Maryland , and among other things he cultivated his friendship with the future American President William Howard Taft during numerous rounds of golf. Anecdotes about his golf game, such as a round of 75 on his 75th birthday, were part of his image in the public eye and were regularly part of the nationwide reporting on his work until the end of his life.

After 34 years as a Supreme Court judge, he died unexpectedly and probably of pneumonia on October 14, 1911. He thus reached the fifth-longest term in the court's history and was still active in the court until five days before his death. The predominantly black-attended Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopalian Church in Washington DC, where he was one of the few whites to attend the funeral of the black writer Frederick Douglass in 1895 , held a memorial service in his honor. This began musically with the funeral march “Marcia funebre sulla morte d'un Eroe” (on the death of a hero), the third movement of the piano sonata No. 12 by Ludwig van Beethoven . His grave is in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington. Harlan's successor was Mahlon Pitney on March 18, 1912 .

In 2002, the memoirs of his wife, with whom he was married for more than 50 years, were published under the title "Some Memories of a long Life, 1854-1911" . The manuscript, which she wrote four years after his death, was kept unpublished in the Library of Congress for decades and discovered through research by Ruth Bader Ginsburg , a Supreme Court judge since 1993. At the request of his children, Harlan himself wrote a series of biographical essays shortly before his death, which in particular included memories of his experiences during the civil war and his political work.

Reception and aftermath

Possible reasons for his change of heart

There are several speculations as to the causes of the fundamental change in Harlan's view of slavery. For one, it is possible that he saw the move to the Republicans and their views as appropriate for his further political career. On the other hand, it also seems likely that his previous public support for slavery was also more in line with political calculations due to the mood in his home state of Kentucky than his actual stance. There are several pieces of evidence that suggest that his private opinion was much more liberal. His father, himself a slave owner, had already taken a paternalistic stance with regard to the treatment of slaves and abhorred the slave trade and brutal treatment of slaves.

Harlan's teachers at Center College and Transylvania University also likely influenced his opinion in favor of a more liberal stance, as did his wife, who, because of her upbringing in a liberal home, rejected slavery. Another, albeit speculative, aspect was his possible half-brother Robert James Harlan, who, as a slave, had been treated almost like a full member of the family. DNA tests carried out in 2001 with the offspring of Robert James Harlan and John Marshall Harlan showed only a low probability of a common father. Other surviving evidence such as the very light skin color of Robert James Harlan and the privileged treatment on the property of the John Marshall Harlans, including an appropriate education and training, speak for a possible relationship.

Harlan was appalled by the violence emanated from the Ku Klux Klan after the civil war. In addition, he had a close friendship with Benjamin Bristow for many years. He had been an active member of the Republican Party even before Harlan's change of heart and had campaigned, among other things, for the entry into force of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. As a public prosecutor from May 1866 to the end of 1869, Bristow passionately persecuted racist perpetrators. He probably also influenced the change in Harlan's attitude. It is also believed that Harlan's attitude to civil rights was influenced by the social principles of the Presbyterians , where he held the office of elder . While serving as a judge, he taught a Sunday school class at a Presbyterian church in Washington.

Lifetime Achievement and Evaluation

Harlan went down as one of the most famous deviants in the history of the Supreme Court due to his frequent minority votes, with which he expressed his for the time liberal views against a conservative majority in the court. In the 1,161 statements that he gave in the course of his career in the court's decisions, he deviated from the majority opinion in 316, around one in four. At that time, the number of his minor opinions was only exceeded by Peter Vivian Daniel , who was a member of the court from 1841 to 1860. In 745 judgments, Harlan himself authored the opinion of the majority of the court and in 100 others a comment in favor of the majority. He was involved in more than half of all decisions from the founding of the court to his death and is considered to be one of the most active, articulate, professionally competent and independent judges in the history of the court.

Center College as his alma mater, as well as Bowdoin College , Princeton University and the University of Pennsylvania awarded him honorary doctorates . His grandson John Marshall Harlan II , who also served as constitutional judge from 1955 to 1971, was also known as a great dissenter . In contrast to Harlan, however, his grandson was a conservative deviator at the liberal court under the presiding judge Earl Warren . With regard to the inclusion of the Bill of Rights in the provisions of the 14th Amendment, for example, his grandson's opinion was the opposite of Harlan's opinion. With his vote on the decisions McLaughlin v. Florida (1964) and Loving v. Virginia (1967) also helped his grandson overturn the Harlan-backed judgment in the Pace v. Alabama involved.

After he was viewed by many of his fellow men as headstrong and difficult to predict during his lifetime, Harlan was considered an “eccentric exception” in the history of the court after his death until the late 1940s due to his decisions. Although he was said to go to bed with the Bible in one hand and the Constitution in the other, his golf clubs under his pillow, and that he attached religious importance to reverence for the Constitution, he generally grew stronger perceived as an ideologically motivated activist and less as a lawyer and almost completely ignored in historiography for around four decades after his death. Beginning with an article published in 1949, however, his perception and evaluation among American lawyers and historians changed to the point that he is now regarded as one of the most outstanding, controversial, and visionary constitutional judges in United States history.

In a 1970 survey titled “Rating Supreme Court Justices,” conducted by law professors Albert P. Blaustein of Rutgers University and Roy M. Mersky of the University of Texas , John Marshall Harlan was among the twelve Supreme Court judges of the involved 65 university teachers for legal or political science and history were rated the highest of five categories ( "great"). A number of the positions expressed in his minor opinions became part of legal practice in the United States through subsequent court decisions or as a result of legislation. His minority vote in Plessy v. Ferguson is considered the most important decision of his career and one of the few minority opinions in the history of the Court of Justice with far-reaching historical significance.

Of Thurgood Marshall , a prominent advocate for the civil rights movement and later 1967-1991 the first judge of African-American descent on the Supreme Court, is narrated that he during the trial on the case of v Brown. Board of Education by reading aloud some passages from Harlan's vote on Plessy v. Ferguson motivated. Harlan's statement “Our constitution is color-blind” - “Our constitution is blind to skin color” - became Thurgood Marshall's leitmotif of his commitment to civil rights.

Individual evidence

- ^ Albert P. Blaustein, Roy M. Mersky: Rating Supreme Court Justices. In: ABA Journal. 58/1972. American Bar Association, pp. 1183-1190, ISSN 0747-0088

-

↑ The biographical information comes from the following sources:

- Chronology of John Marshall Harlan. Available online at www.law.louisville.edu/library/collections/harlan/chronology

- Clare Cushman: Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies 1789–1995. 2nd edition. CQ Press, Washington DC 1996, pp. 216-220, ISBN 1-56802-126-7

- Louis Filler: John M. Harlan. In: Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel: The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers, New York 1995, pp. 627-642, ISBN 0-7910-1377-4

- ^ Alpheus Harlan: The History and Genealogy of the Harlan Family. Baltimore, Maryland 1914, reprinted 1987

- ↑ a b c d e Linda Przybyszewski: The Dissents of John Marshall Harlan I. In: Journal of Supreme Court History. 32 (2 )/2007. Supreme Court Historical Society, pp. 152-161, ISSN 1059-4329

- ↑ a b c d e f Charles Thompson: Harlan's Great Dissent. In: Kentucky Humanities. 1/1996, Kentucky Humanities Council, Lexington, Kentucky

- ^ A b Peter Scott Campbell: John Marshall Harlan's Political Memoir. In: Journal of Supreme Court History. 33 (3) / 2008. Supreme Court Historical Society, pp. 304-321, ISSN 1059-4329

- ↑ HarpWeek: Explore History - Elections - 1876 Hayes v. Tilden Overview online , Harper's Weekly

- ↑ Loren P. Beth: President Hayes Appoints a Justice. In: Supreme Court Historical Society 1989 Yearbook. The Supreme Court Historical Society, Washington DC 1989

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Henry J. Abraham: John Marshall Harlan: A Justice Neglected. In: Virginia Law Review. 41 (7) / 1955. Virginia Law Review Association, pp. 871-891, ISSN 0042-6601

- ^ Alan F. Westin: John Marshall Harlan and the Constitutional Rights of Negroes: The Transformation of a Southerner. In: Yale Law Journal. 66 (5) / 1957. The Yale Law Journal Company, Inc., pp. 637-710, ISSN 0044-0094

- ^ Howard Zinn : A People's History of the United States . Harper Perennial, New York 2005, ISBN 0-06-083865-5 , pp. 204/205

- ↑ C. Ellen Connally: Justice Harlan's "Great Betrayal"? A Reconsideration of Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education. In: Journal of Supreme Court History. 25 (1) / 2000. Blackwell Publishing, pp. 72-92, ISSN 1059-4329

- ↑ Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education. 175 U.S. 528,1899; Online at http://supreme.justia.com/us/175/528/case.html

- ↑ a b c German translation based on Plessy v. Ferguson. 163 U.S. 537,1896; Online at http://supreme.justia.com/us/163/537/case.html

- ↑ Gabriel J. Chin: The Plessy Myth: Justice Harlan and the Chinese Cases. In: Iowa Law Review. 82/1996. University of Iowa College of Law, pp. 151-182, ISSN 0021-0552

- ↑ US v. Wong Kim Ark. 169 U.S. 649,1898; Online at http://supreme.justia.com/us/169/649/case.html

- ^ A b Ross E. Davies: The Judicial and Ancient Game: James Wilson, John Marshall Harlan, and the Beginnings of Golf at the Supreme Court. In: Journal of Supreme Court History. 35 (2) / 2010. Supreme Court Historical Society, pp. 122-143, ISSN 1059-4329 (on John Marshall Harlan, specifically pp. 124-129)

- ↑ Louis Filler: John M. Harlan. In: Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel: The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers, New York 1995, pp. 627-642, ISBN 0-7910-1377-4

- ^ The Associated Press: DNA tests show no link between justice, ex-slave. In: The Courier-Journal. September 3, 2001, Louisville, Kentucky

- ^ A b G. Edward White: John Marshall Harlan I: The Precursor. In: American Journal of Legal History. 19 (1) / 1975. Temple University School of Law, pp. 1-21, ISSN 0002-9319

- ^ Richard F. Watt and Richard M. Orlikoff: The Coming Vindication of Mr. Justice Harlan. In: Illinois Law Review. 44/1949. University of Illinois College of Law, pp. 13-40, ISSN 0276-9948

- ↑ Rating Supreme Court Justices. In: Henry Julian Abraham: Justices, Presidents and Senators: A History of the US Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham 2007, ISBN 0-7425-5895-9 , pp. 373-376

literature

- Linda Przybyszewski: The Republic According to John Marshall Harlan. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1999, ISBN 0-8078-4789-5

- Loren P. Beth: John Marshall Harlan: The Last Whig Justice. University Press of Kentucky, Lexington 1992, ISBN 0-8131-1778-X

- Malvina Shanklin Harlan: Some Memories of a long Life, 1854-1911. Modern Library, New York 2002, ISBN 0-679-64262-5

- John Marshall Harlan. In: D. Grier Stephenson: The Waite Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2003, ISBN 1-57607-829-9 , pp. 110-117

- John Marshall Harlan. In: James W. Ely: The Fuller Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2003, ISBN 1-57607-714-4 , pp. 43-46

- John Marshall Harlan (1833-1911). In: Rebecca S. Shoemaker: The White Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2004, ISBN 1-57607-973-2 , pp. 35-40

Web links

- The Oyez Project - John M. Harlan (English)

- University of Louisville, Louis D. Brandeis School of Law Library - The John Marshall Harlan Collection Collection of documents from John M. Harlan (English)

- History of the Sixth Circuit - John Marshall Harlan Bibliography Collection of publications on Harlan

- Landmark Supreme Court Cases - Plessy v. Ferguson information on the case of Plessy v. Ferguson (English)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Harlan, John Marshall |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American federal judge |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 1, 1833 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Boyle County , Kentucky |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 14, 1911 |

| Place of death | Washington, DC |