Loving v. Virginia

| Loving v. Virginia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Negotiated April 10, 1967 |

||||

| Decided June 12, 1967 |

||||

|

||||

| facts | ||||

| Appeal for a criminal sentence against a couple for a so-called "multiracial" marriage | ||||

| decision | ||||

| The ban on marriage between whites and non-whites is a violation of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. | ||||

| occupation | ||||

|

||||

| Positions | ||||

|

||||

| Applied Law | ||||

| United States Constitution , 14th Amendment ; Virginia State Racial Integrity Act of 1924 (Sections 20–58, 20–59) |

Loving v (ersus) Virginia ("Loving v Virginia") is a ruling by the United States Supreme Court that repealed a Virginia law in 1967 that prohibited so-called "multiracial" marriages between white and non-white partners . The trial came on the case of Richard and Mildred Loving , who had been convicted of their marriage in Washington, DC under a law in force in Virginia since 1924 , because Richard was considered white , while Mildred was of African-American and Native American ancestry . The ruling by the Supreme Court in favor of the couple, which was unanimous, marked the legal end of all skin color- based restrictions on marriage and is therefore considered a landmark decision in the history of the court and a milestone in the American civil rights movement .

Facts of the case

Richard Perry Loving, a white man born in 1933, and Mildred Delores Jeter , six years his junior , of both African American and Native American ancestors, had married in Washington, DC in June 1958 . In her home state of Virginia , the Racial Integrity Act , passed in 1924, prohibited marriages between whites and non-whites:

Punishment for marriage. —If any white person intermarry with a colored person, or any colored person intermarry with a white person, he shall be guilty of a felony and shall be punished by confinement in the penitentiary for not less than one nor more than five years.

After their return to Virginia, they were arrested by three police officers in the bed of their house in the morning of July 1958 and charged with violating this law, which, according to Section 20-58, also prohibited “multiracial” marriages outside the state for residents of Virginia if the Spouses subsequently returned to Virginia. The marriage certificate hung in the couple's bedroom became prosecution evidence in this regard . Until the trial, both lived separately with their parents. For the offense they were charged with, they faced a prison sentence of between one and five years under sections 20-59 of the Code of Virginia (1950) .

Judgments of the lower courts

In January 1959, Richard and Mildred Loving pleaded guilty to the Caroline County District Court and sentenced them to one year in prison. The sentence was suspended by agreement , provided that the married couple would leave the state of Virginia and not enter Virginia together for at least 25 years. The responsible judge Leon Bazile justified his decision with the following statements, among other things:

“[...] God Almighty created the races, white, black, yellow, Malays and red, and he assigned them to different continents. And there is no reason for such marriages other than those brought about by his providence. The fact that he separated the races is evidence that he did not intend the races to mix. [...] "

As a result of the verdict, Richard and Mildred Loving moved to Washington DC, where both suffered from the physical separation from their families and their home, and Mildred Loving in particular could not endure the exclusion resulting from the verdict. On November 6, 1963, with the assistance of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), they filed a motion to have the sentence and sentence set aside in the appropriate district court. The basis was the principle of equal treatment contained in the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution . The motivation of Richard and Mildred Loving is expressed by a statement by Richard Loving, which has been passed down through the attorney Bernard Cohen, who was involved in the case for the ACLU:

"Mr. Cohen, tell the court that I love my wife and that it is just unfair that I cannot live with her in Virginia. "

The case reached the United States District Court for East Virginia, after the District Court rejected the motion to set aside the sentence and the sentence , which referred the case to the Virginia State Supreme Court of Appeals. This confirmed both the conviction and the law on which it was based on March 7, 1966. The court rejected the existence of a violation of the principle of equal treatment on the grounds that both partners had received the same sentence. In the period between the filing of the motion and the Supreme Court acceptance of the case, both the Presbyterian and Roman Catholic Churches in the United States and the Unitarian Universalist Association announced their support for the repeal of all existing laws against "multiracial" marriage . After the Supreme Court ruled to hear the case on December 12, 1966, the Maryland state ban was lifted before the verdict was announced.

Supreme Court decision

The history of the Supreme Court up until the Loving v. Virginia is not yet directly concerned with the constitutionality of "multiracial" marriage laws. In the case of Pace v. Alabama , which concerned a ban on sexual intercourse between whites and non-whites in the state of Alabama , the majority of the courts had reached a decision in 1883 that such a ban would not violate the principle of equal treatment, since both partners involved would receive the same punishment. Another potentially pertinent case involving the annulment of a marriage between a white man and a partially black woman under an Arizona state law resulting from an inheritance dispute was not accepted for decision by the Supreme Court in 1942 been.

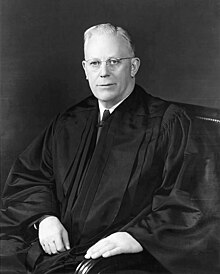

In the case of Loving v. Virginia , chaired by Judge Earl Warren, presided over by a unanimous decision, overturned Richard and Mildred Loving's conviction and declared the Virginia State's underlying Racial Integrity Act to be unconstitutional. Following the ACLU's request, it recognized in the law a violation of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, both according to the ACLU's argument based on the principle of equal treatment and, furthermore, on the basis of the principle of legal certainty . The judges wrote, among other things, in their decision, written by Earl Warren:

“[...] Getting married is one of the fundamental civil rights of people, fundamental to our existence and our continued existence. [...] Denial of this right on such an intolerable basis as the racial characteristics contained in this law, a classification that directly contradicts the principle of equal treatment in the 14th Amendment, certainly constitutes an unlawful denial of freedoms for the citizens of the state. The 14th Amendment requires that freedom to get married not be restricted by hurtful racial discrimination. According to our constitution, the freedom to marry or not to marry someone of another race rests with the individual and cannot be restricted by the state. [...] "

The court rejected the argument that the Virginia ban on “multiracial” marriages would not violate the principle of equal treatment because both partners involved receive the same punishment. It also emphasized the need for the establishment of a law resulting from the 14th Amendment, expressly stating that laws against marriages between whites and non-whites are racist and were passed in order to preserve the superiority of whites :

“[...] There is obviously no overriding purpose that justifies this classification, regardless of hurtful racial discrimination. The fact that Virginia only prohibits multiracial marriages involving white people shows that the racial classification is based on its own justification, as a measure to maintain white supremacy. [...] "

In a special vote in favor of the majority of the court, Judge Potter Stewart referred explicitly to his three years earlier in the McLaughlin v. Florida expressed the view that "no law of a state can be constitutional which makes the criminality of an act dependent on the race of the agent".

Effects of the judgment

According to civil rights activists, the ruling of the Supreme Court removed one of the last remaining legal restrictions from the era of slavery in the United States and accelerated the then existing trend towards increasing social acceptance of marriages and unions between people of different skin colors and origins . In 2008, around four decades after the decision, there were around 4.3 million such marriages in the United States, according to the United States Census Bureau . The ruling was also seen as completing the process of racial segregation abolished by the Supreme Court in 1954 in the Brown v. Board of Education had started.

In addition, the decision fundamentally influenced the understanding of marriage and family in American society, as it legally recognized the inviolability of marriage. The Racial Integrity Act , the prohibition of "multiracial" marriages no longer applied by the court decision, was completely overridden by the Virginia State Parliament in 1975. Legal regulations in 15 other states that were comparable to this law were subsequently amended by Loving v. Virginia also abolished or no longer enforced. However, it was not until 2000 that the last law against "multiracial" marriages was formally repealed in Alabama .

Richard and Mildred Loving moved back to Virginia after the verdict. Their marriage resulted in two sons and a daughter. Richard Loving was killed in a traffic accident in June 1975 at the age of 41 in which a drunk driver rammed the vehicle in which he and his wife were driving. Mildred Loving died in May 2008 at a pneumonia . About a year before her death, on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of Loving v. Virginia on her understanding of the personal and social significance of the decision:

“[...] When my husband Richard and I got married in Washington DC in 1958, we did not do this to send a political message or to start an argument. […] My generation was deeply divided over something that should have been so clear and correct. […] But I've lived long enough to see big changes. The fears and prejudices of the older generation are a thing of the past, and today's young people have realized that someone who loves someone has a right to marry. Surrounded by wonderful children and grandchildren, not a day goes by without thinking of Richard and our love, our right to marry and how much it meant to me to have the freedom to marry the person I love, even if others believed , he would be the wrong person for me. I believe that all Americans regardless of race, gender, or sexual orientation should have equal freedom to marry. […] I am still not a politically active person, but I am proud that Richards and my name designate a court ruling that can help strengthen the love, devotion, fairness and family that so many people, blacks, have and strive for whites, young and old, homosexuals and heterosexuals, in their lives. [...] "

In addition to its importance for the end of racial segregation, the decision of Loving v. Virginia and the underlying reasoning with the principle of equal treatment of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution also discussed in the debate about the legalization of same-sex marriages in the USA. However, the New York Court of Appeals , the highest court in New York State , decided in July 2006 in the decision of Hernandez v. Robles refused. The reason given by the court included the fact that the historical development of slavery and the civil rights movement would be fundamentally different from the historical and social background of efforts to permit same-sex marriages and that the judges of the Supreme Court in the decision of Loving v. Virginia would have recognized the right to marriage as fundamental, particularly because of its relationship to human reproduction . However, this was confirmed by the Supreme Court in the Obergefell v. Hodges decided differently in 2015, in which the right of same-sex couples to marry with reference to Loving v. Virginia narrowly confirmed it.

reception

About the couple's life story, a television film was made in 1996 under the title Mr. & Mrs. Loving , in which Timothy Hutton played the role of Richard Loving and Mildred Loving was portrayed by Lela Rochon .

The 2011 documentary The Loving Story was directed by Nancy Buirski .

In 2016, director Jeff Nichols filmed the case again under the title Loving . Joel Edgerton took on the role of Richard Loving and Ruth Negga that of Mildred Loving. The film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival 2016 .

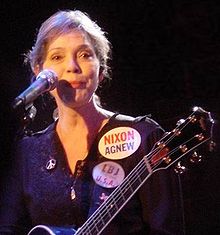

On the 2009 album The Loving Kind by the American country and folk singer Nanci Griffith , the title song addresses the judgment and fate of Richard and Mildred Loving.

June 12, the day of judgment in 1967, is celebrated annually by various organizations under the name Loving Day as a commemorative and public holiday.

literature

Primary literature:

- Philip B. Kurland and Gerhard Casper (Eds.): Landmark Briefs and Arguments of the Supreme Court of the United States: Constitutional Law . tape LXIV . Arlington 1975, p. 687-1007 .

Secondary literature:

- Karen Alonso: Loving v. Virginia: Interracial Marriage (Landmark Supreme Court Cases). Enslow Publishers, Berkeley Heights 2000, ISBN 0-7660-1338-3 .

- Peter Wallenstein: Tell the Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage, and Law - An American History. Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2004, ISBN 1-4039-6408-4 .

- Susan Dudley Gold: Loving v. Virginia: Lifting the Ban Against Interracial Marriage (Supreme Court Milestones). Marshall Cavendish Benchmark, New York 2007, ISBN 0-7614-2586-1 .

- Phyl Newbeck: Virginia Hasn't Always Been for Lovers: Interracial Marriage Bans and the Case of Richard and Mildred Loving. Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale 2008, ISBN 0-8093-2857-7 .

- Walter Wadlington: The Loving Case: Virginia's Anti-Miscegenation Statute in Historical Perspective . In: Virginia Law Review . tape 62 , no. 7 . Virginia Law Review Association, 1966, ISSN 0042-6601 , pp. 1189-1223 .

- Robert A. Pratt: A Historical Assessment and Personal Narrative of Loving v. Virginia . In: Howard Law Journal . tape 41 , no. 2 . Howard University School of Law, 1998, ISSN 0018-6813 , pp. 229-244 .

- Robert J. Sickels: Race, Marriage and the Law . University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque 1972, ISBN 978-0-8263-0256-4 .

- Werner Sollors (Ed.): Interracialism: Black-White Intermarriage in American History, Literature, and Law . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, ISBN 978-0-19-512857-4 .

- Joanna L. Grossman and John DeWitt Gregory: The Legacy of Loving . In: Howard Law Journal . tape 51 , no. 1 . Howard University School of Law, 2007, ISSN 0018-6813 , pp. 15-52 .

- Peggy Pascoe: Lionizing Loving . In: What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2009, ISBN 978-0-19-509463-3 .

- Paul Lombardo: Miscegenation, Eugenics, and Racism: Historical Footnotes to Loving v. Virginia . In: UC Davis Law Review . tape 21 , no. 2 . UC Davis School of Law, 1988, ISSN 0197-4564 , p. 421-452 .

- Mark Strasser: Loving in the New Millennium: On Equal Protection and the Right to Marry . In: University of Chicago Law School Roundtable . tape 7 . The University of Chicago Law School, 2000, ISSN 1075-9166 , pp. 61-90 .

- Robert A. Destro: Introduction to Symposium, Law and the Politics of Marriage: Loving v. Virginia After 30 Years . In: Catholic University Law Review . tape 47 . CUA Law Review Association, 1998, ISSN 0008-8390 , p. 1222-1226 .

Audio documents

- Audio documents for the hearing at Oyez.org

- Peter Irons and Stephanie Guitton (Eds.): May It Please the Court. The Most Significant Oral Arguments Made Before the Supreme Court Since 1955 . New Press, New York 2007, ISBN 978-1-59558-090-0 (Includes a CD with recordings of the hearing).

Web links

- Loving v. Virginia , 388 US 1 (1967) Full Text of Judgment

- Loving v Virginia: Couple fighting for desegregation in one day

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d David Margolick: A Mixed Marriage's 25th Anniversary of Legality In: The New York Times . Edition of June 12, 1992, p. 20

- ↑ a b c Loving v. Virginia. 388 U.S. 1, 1967; Online at http://supreme.justia.com/us/388/1/index.html

- ^ A b Douglas Martin: Mildred Loving, Who Battled Ban on Mixed-Race Marriage, Dies at 68 In: The New York Times . Edition May 6, 2008

- ^ A b c John DeWitt Gregory, Joanna L. Grossman: The Legacy of Loving. In: Howard Law Journal. Issue 51 (1) / 2007. Howard University School of Law, pp. 15-52, ISSN 0018-6813

- ↑ Unitarian Universalist Association: 1966 Business Resolution: Consensus on Racial Justice ( Memento of September 4, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (English; accessed October 20, 2009)

- ↑ Pace v. Alabama. 106 U.S. 583,1883; Online at http://supreme.justia.com/us/106/583/index.html

- ^ A b c Peter Wallenstein: The Right to Marry: Loving v. Virginia. In: OAH Magazine of History. 9 (2 )/1995. Organization of American Historians, pp. 37-41, ISSN 0882-228X

- ↑ Mr. Justice Stewart, concurring. In: Loving v. Virginia. 388 U.S. 1, 1967; Online at http://supreme.justia.com/us/388/1/index.html

- ↑ Patricia Sullivan: Quiet Va. Wife Ended Interracial Marriage Ban In: The Washington Post . Edition May 6, 2008

- ↑ Bárbara C. Cruz Michael J. Berson: The American Melting Pot? Miscegenation Laws in the United States. In: OAH Magazine of History. 15 (4) / 2001. Organization of American Historians, pp. 80-84, ISSN 0882-228X

- ↑ Loving for All ( Memento of October 23, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) From a declaration by Mildred Loving on June 12, 2007 on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the decision of Loving v. Virginia ( PDF file , approx. 25 kB)

- ^ Billy Kluttz: Loving v. Virginia and Same Sex Marriage: Mapping the Intersections. In: Culture, Society and Praxis. 7 (2) / 2008. California State University, pp. 8-12, ISSN 1544-3159

- ↑ Hernandez v. Robles. 86-89 / 2006; Online at http://www.courts.state.ny.us/ctapps/decisions/jul06/86-89opn06.pdf ( PDF file , approx. 135 kB)

- ↑ Obergefell v. Hodges ; Online at http://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/14pdf/14-556_3204.pdf ( PDF file )

- ↑ Mr. & Mrs. Loving in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ Cannes Film Review: 'Loving' at variety.com, accessed May 15, 2016

- ↑ What is Loving Day? (English; accessed October 18, 2009)