Erich Hylla

Erich Hylla (born May 9, 1887 in Breslau ; † November 5, 1976 in Frankfurt am Main ) was a German educator , author and publicist . He dealt with work on pedagogical diagnostics, talent research and comparative educational science.

Life

Teacher training, studies and first professional steps

The craftsman's son Erich Hylla attended elementary school in his hometown, then a preparatory institute and then the teachers' seminar in Brieg , where he passed the first teacher examination in 1907. In the same year Hylla became a member of the German Teachers' Association .

From 1907 to 1909 Hylla worked as a primary school teacher at a rural school and in 1909 passed the second teacher examination. In 1909 he moved to Breslau , where he worked as a primary school teacher and continued his education in parallel. In several subjects he passed the secondary school teacher examination and studied psychology with William Stern . Here he experienced a form that was of great importance for his further professional and scientific life.

“The fruit of this study was the first German form of the Binet test , which he worked out with Bobertag. Hylla never let go of the work on test research. Many test series followed the first, and they were never an end in themselves, but all served the teacher's basic concern of recognizing talent and ensuring that the individual was educated according to his or her talent, especially during the 'transition from primary school to secondary school'. "

In 1914, Hylla moved to a secondary school in Berlin and passed the rector's examination in 1915. In 1919 he moved to Stettin as a high school principal , and from 1920 to 1922 he still studied pedagogy in Berlin. From 1921 to 1922 he was also a school councilor in Eberswalde .

School reformer during the Weimar period

Erich Hylla was appointed to the Prussian Ministry of Culture in 1922 , which was headed by Carl Heinrich Becker . His first work there was the creation of the "Guidelines for the preparation of curricula for the upper classes of elementary school". In addition to this work in the ministry, he was also an employee at the Central Institute for Education and Teaching and was active in the German Teachers' Association (DLV). He worked in its “Pedagogical Headquarters” and was a consultant for psychology in the editorial team of the “Deutsche Schule” magazine published by the DLV.

In 1926/27 the Prussian Ministry of Culture made it possible for him to study in the USA. Here he met Richard Thomas Alexander , the director of a college responsible for teacher training at Columbia University . It was his former assistant, John W. Taylor, who appointed Hylla as a specialist advisor on educational issues to the American military government in 1946. But this trip to the USA was also of great scientific importance for Hylla.

“Your study trip to the United States in 1926 was decisive for your intellectual development. In 1928 you introduced the German public to the development and results of educational research in the United States through your book Die Schule der Demokratie , an outline of the American educational system. In 1930 you published the basic work of the American educator John Dewey Democracy and Education in German translation. "

From 1930 on, Hylla was professor of psychology and education at the newly founded Pedagogical Academy Halle (Saale) , from 1931 Ministerialrat in the Prussian Ministry of Culture. He was a consultant for elementary schools, teacher training, relations with foreign schools. This activity was ended abruptly in 1933: Bernhard Rust , the new National Socialist minister, dismissed him for political unreliability.

Surviving in the time of Nazi rule

The biographical data about the time immediately after Hylla's discharge are poor. Hylla held a visiting professorship in comparative education at Columbia University between 1935 and 1937 and at Cornell University in 1938 . Frank H. Jonas sees in these visiting professorships a kind of key for Hylla's new beginning after 1945: “This experience was to pay off during the postwar years in the joint American and German efforts to modify some German educational practices and to give Americans a better understanding of these practices and problems. "

Hylla returned to Germany after her time at Cornell University . Nothing is known about the reasons, about his time before the visiting professorship it is only said that he was unemployed and that he retired from 1938 to 1945. Frank H. Jonas states: "The war prevented Mr. Hylla from returning to the United States in 1939." However, this leaves open whether there have been any corresponding offers for further stays in the USA, and also why Hylla will continue before a possible further guest professorship Germany traveled and was surprised there by the outbreak of war.

In 1944 Hylla was drafted into the army, but did not complete basic training, but was employed as an interpreter. In 1945 he was taken prisoner by the Americans in Bavaria.

New beginning 1945

After his release from captivity, he, "the Prussian Hylla, built up the local school system in Landsberg am Lech in 1945 and 1946 as a Bavarian school councilor". But already in 1946 his old friend from the American days, Richard Thomas Alexander, made him a specialist advisor in the education department of the US High Commissioner.

"As the educational systems began functioning along older lines, E&RA strength rose to forty officials by mid-1946. Because of its lowly status within the military government, E&RA was unable to attract a prominent American education expert to lead it. Military Governor Lucius D. Clay was, therefore, forced to appoint his unknown section chief, John W. Taylor, who had a doctorate in education from Columbia Teachers College. Taylor then enlisted his old mentor, Richard Thomas Alexander, as his adviser. Both were well acquainted with prewar German education. An outspoken critic of the traditional multitrack system, Alexander enlisted German reformers, such as the Prussian education expert Erich Hylla, in his cause. "

At that time, Fritz Karsen was pushing ahead with planning a German research university in Berlin . His plans included an “institute for educational research” as an integral part. For Karsen, “the establishment of an institute for scientific pedagogy was [indispensable], as this subject area had hitherto been severely neglected in Germany. It would be the only new institute to be founded within the research university and it would have a relatively high budget of half a million RM, five to six professors and ten to twelve assistants. ”At the same time, Erich Hylla, who in late summer, developed astonishingly similar considerations In 1946 accompanied the Zook Commission on their journey through the American zone of occupation . In their report, based on the earlier Central Institute for Education and Teaching (see above) , he suggests “the establishment of a body for educational research and services”. His reason for this:

“The educational research at the German universities is now almost entirely limited to problems of the philosophy and theory of education. Questions of school administration, school maintenance, measurements and tests of school buildings and equipment, teacher training, curriculum design, even educational and child psychology are badly neglected. Pedagogical inventories are practically unknown. [..] The proposed institute should take up all these problems, serve as a 'clearing house', publish an educational bibliography and a monthly, collect material and make it available to educational or administrative offices in Germany and abroad, organize the exchange of teachers and students , Set up courses for foreign educators for German teachers and set up an educational library. In all of these things the United States could provide assistance through government agencies and voluntary organizations. In view of the current economic situation in Germany, it would be difficult to set up such an institute without such economic help. "

Erwin Stein, who had already taken part in the negotiations on the establishment of the German Research University as a representative of Hesse , got to know Hylla as an employee of the American military administration and remembered his saying that he was "jointly responsible for some things that happened and what didn't happen" . At the same time, Stein stated: In you I found an energetic sponsor for my plan, which was presented to the public in 1948, to create a university for educational science for international research, thanks to your support and the help of the United States, the state of Hesse and the city of Frankfurt am Main, the University for International Educational Research was established in Frankfurt am Main on November 16, 1950, and since October 25, 1951, it has been recognized as a foundation under public law that is independent of the state. What was more obvious to me than to appoint you as the director of this university and professor of educational psychology. The “obvious” for Stein took place in two steps. The first was Hylla's assignment to build the new college on November 16, 1950; the second his appointment as professor and director of the university - today DIPF | Leibniz Institute for Research and Information in Education - on May 16, 1952.

Hylla's ideas about educational research

Before going into the founding history of the University for International Educational Research in more detail, I should briefly outline what Hylla's ideas were for future educational research. In the essay, Tasks of Pedagogical Research , published in 1948, he specified the ideas that he had outlined in the report of the Zook Commission cited above . Again based on the educational research that has hitherto been neglected in Germany, which he also attaches to the fact that "among the many Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes [...] there was not one that would have served research in the field of education" , he pleads for concentration on the bare essentials, and for him that is educational factual research . His appraisal of her is bleak: “Here, of course, the situation is also the most difficult; for here the neglect has been greatest. In many cases, it has to be rebuilt from the ground up, because even before 1933 facilities that appear to be particularly important in this context, and which could at least be used as a starting point, were in some cases not available at all. ”Against this background, he describes five main areas, which should primarily be established as research priorities.

- The Comparative Education is the first area, the lack of which he complains in Germany and the establishment of which he now insists. "It requires a careful study of foreign education, especially of those countries whose overall cultural situation is somewhat comparable to ours, or whose educational ideas are of particular interest to us today for other reasons." For the neglect of this research area he makes - besides political difficulties during the Nazi era - primarily mental reasons responsible: “Thorough comparative examinations cannot only be carried out at the desk or in the library; they require personal, direct acquaintance with the educational system abroad, which can only be gained with some command of the language and on the spot. "

- Another very neglected area for Hylla is educational psychology . Against the background of his own training with William Stern and his collaboration with Otto Bobertag (see above), this area is particularly broad. He criticizes the lack and at the same time calls for the development of measuring instruments for talent and school management tests. “A measuring tracking of the development of the young person or the measuring, objective assessment of his achievements should form one of the essential bases for answering the question whether and to what extent certain teaching materials, teaching forms, school types are appropriate and useful. The fact that we lack all documents of this kind is one of the reasons for the sterility and the unscientific character of all our discussions on questions of school reform: They are disputes among interest groups who cannot convince each other and who do not want to be convinced. There is little hope of improvement as long as reliable, objective methods of establishing facts are not developed, applied, understood by the teaching staff and used to a certain extent, as is the case with e.g. B. is the case in the United States. "

- The next point whose scientific underexposure makes Hylla “is the design of the schoolwork itself: curriculum, teaching method, teaching. and learning aids . Our curricula have so far been created almost exclusively on the basis of official regulations. Even where the official bodies have sought the collaboration of broad circles, such as the teaching staff or even - which rarely happened - lay groups, in the end it was always tradition and theoretical discussions from which the curriculum grew. ”With the same radicalism he presents the traditional teaching methods and the materials used and calls for extensive factual investigations on the basis of calibrated test series.

- Another area for which he has so far lamented the lack of any scientific penetration is the area of school administration, school maintenance and school supervision . He states that “the entire concept of school administration is still in a very pre-academic stage of development” and demands: “Questions such as the breakdown of the school administration offices, their relationships to one another, the number of administrative levels, etc. were answered from the point of view of current practical expediency should be subjected to a scientific investigation as well as that of the school structure, the delimitation of the school districts, the design of school buildings, the school registry, the creation and management of personnel files, the teacher evaluation, etc. School administration and Teachable school supervision, a more efficient school administration will have to be created in Germany. "

- Hylla's fifth and final point for a carefully developed factual educational research is the field of school statistics . He calls for more meaningful surveys of social and school-related student data as well as data that provides decision-making aids in questions of the “reorganization of the school structure, the school types, teacher training, school maintenance, school fees, teaching and learning materials [..] But above all, there is It must be ensured that the school statistics work also has the opportunity to develop its concepts and methods theoretically and to train a trained young generation according to plan. "

Hylla pleads for the elimination of the misery he noted for the establishment of research centers to train skilled workers . At the time, however, he did not see these research centers as independent institutions; instead, despite his vehement criticism of the lack of practical application in university education, he favored research institutes at universities as the focal points of the educational faculties there. “There you would be able to make a significant contribution to the training of future teachers who are really trained in pedagogical science for the schools, but above all the additional training in the educational practice of already established men and women for leading positions in school supervision and school administration as well as the preliminary training of a substantial part of teacher trainers and future university teachers of pedagogy. The connection between research and teaching would naturally find the strengths in the students who could deal with and solve real-life and contemporary tasks of educational factual research in the preparation of their dissertations, examination papers or habilitation theses. "

Hylla does not fail to recognize the difficulties that stand in the way of the realization of his ideas, and as far as the material difficulties are concerned, he fully trusts the support of the Americans. He also suggests that younger German school-leavers who might be considered as junior lecturers should be sent to the USA for further training. On the other hand, however, he is aware that the development of educational factual research is only a partial task, because “this is only a partial task of a larger and more comprehensive one: the transformation of the German educational system from one to one through tradition and political ideology certain system into a living organ of a people's body that serves the needs of all ethnic groups equally, is geared to the present and the future, and which is only just beginning to transform itself into a democratic one and is to be won over for international work. Only in proportion with this transformation and the corresponding general transformation of the educational system can the sub-task dealt with here be promoted. It is only in connection with it that it has fundamental meaning and meaning. So we want to approach them with all our zeal, but at the same time arm ourselves against disappointments by keeping in mind from the outset that tasks of this size can hardly be solved faster than in a generation. "

When Hylla wrote this, he was still under the spell of the recommendations of the Zook Commission , on which he himself had worked and which aimed at a more democratic education system. One of the last directives of the Allied Control Council, which was issued as ACC No. 54 on June 25, 1947 in Berlin, was based on these recommendations. The directive concerned “Basic Principles for Democratization of Education in Germany” and, in the fourth out of 10 points, aimed at the introduction of a tiered instead of a structured education system. Democratization of the school system was the core idea and the German grammar school privilege was called into question. But as the example of the German Research University had already shown: There were good decisions on the American side, but they often fizzled out. So here too: “The directive of the control council and the report of the ZOOK commission were fought in Hesse, parts of Baden and Württemberg as well as in Bavaria, i.e. the four large areas of the American occupation zone, particularly with a view to questioning the high school privilege. The American military governor LUCIUS D. CLAY issued the order on January 10, 1947, to fundamentally change the education system in his area of responsibility. On August 9, 1948, the American military government ordered the introduction of a six-year elementary school for all children, but this was never implemented in Hesse, Bavaria or Baden-Württemberg. At this point the re-education failed even before it had really started. I related re-education to teaching materials, public media or the climate of opinion in the young Federal Republic, but not to the structure of the education system. "

Another question is whether the educational factual research propagated by Hylla , which very well refers to many deficits in German educational science, can contribute to rational decision-making to the extent that he hoped. The discussion about the unified school could be cited as counter-evidence as well as the discussion about the Hessian framework guidelines in the 1970s or the discussion about comprehensive schools that continues to this day . There has never been a lack of well-founded scientific arguments in these disputes, but they did not prevent "disputes among interest groups who cannot convince each other and who do not want to be convinced", as Hylla had already hoped above in connection with educational psychology . And another point: Hylla's pedagogical factual research, thoroughly thought through, would quickly lead to a “transparent school” under the conditions of today's technical possibilities - with the best prerequisites for “predictive educating”. How real such a risk is is shown by the presentation of the negative Big Brother Award to the Conference of Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs on October 20, 2006. This was done for their project to collect cross-national school statistics for pupils and teachers centrally and to collect personal data without the individual educational data To bind purposes and to protect against misuse and unauthorized access.

The University for International Educational Research

The founding process

The proximity of Fritz Karsen's ideas for an institute for scientific pedagogy within the framework of the German Research University, which he was instrumental in advancing, and Erich Hylla's sketch published in 1946 for the establishment of a position for pedagogical research and services was already mentioned above. That this is no coincidence can be inferred from the many overlaps in their two life paths: Both were committed school reformers during the Weimar period, they worked almost at the same time in the Prussian Ministry of Education, took turns during their study visits to the USA and both became theirs there After 1945 they were appointed to important positions in the reconstruction of the German education system. Both were also strongly impressed and influenced by the American education system and endeavored to "confront German pedagogy with the democratic approaches of pragmatism and to lead them on the path of empirical research, which particularly included international comparison". However, Karsen's importance in this context fades against the background of the fact that he returned to the USA in 1948 and thus no longer had any influence on German developments. This presumably gave rise to the somewhat narrowed view of Hylla, who was "a specialist advisor to the head of the education department of the US military governor for Germany and [..] in this function [was] responsible for the renewal of education. The aim of the structural policy was the introduction of a democratic comprehensive school for all children based on the model of the American elementary and high school, i.e. a clear break with the German educational tradition of selective schooling. In addition, the rapid democratization of the universities was declared a goal. "

As the quote at the end of the previous section shows, Erwin Stein also only refers to Hylla, although his draft for a law on teacher training in Hesse of December 1948 provides for the establishment of a "college for educational science and international educational research" which is explicitly located in the context of the "State Agreement on the Establishment of a German Research University in Berlin-Dahlem". As a representative of Hesse on the board of trustees of the German Research University and on the state council, he was also the direct negotiating partner of Karsen from January 1947, who sat opposite him as "Chief, Higher Education and Teacher Training" in the OMGUS's Education and Cultural Relations department . In this context, Karsen's considerations for an institute for scientific pedagogy can hardly have remained hidden from him.

With the American William L. Wrinkle there is another person who is of great importance for the founding phase of the College for International Educational Research .

"Before coming to Germany, Dr. Wrinkle had been professor of secondary education and director of the campus experimental high school at the State College of Education at Greeley in Colorado, having served that institution for 23 years. Through his experience in administering educational programs in Germany, Dr. Wrinkle arrived independently at the same conclusions about educational research in Germany as were entertained by Mr. Hylla. "

Hylla and Wrinkle met in Frankfurt in 1947, where Wrinkle was stationed as "chief of the secondary education section in the Public Education Branch, OMGUS, and now HICOG's educational affairs adviser".

"THIS MEETING brought reality to the old dream, now shared by both men, resulting in the association which was to gain the necessary support from German and American sources for the creating of the Institute for International Educational Research. The development of the idea of a graduate school of this type in Germany could never have proceeded to its present successful conclusion without the close cooperation and teamwork of these two educators. [..] Professors Hylla and Wrinkle, sensing official German interest in such an institution, approached Dr. Stein in Wiesbaden. As a result, the Society for Educational Research and Advanced Studies in Education was organized, with Dr. Stein as president and Mr. Hylla as executive secretary. This society, which was composed of Hessian educational leaders interested in this movement, sponsored the Institute. "

The quote refers to another actor in the founding process of the university: the “Society for Educational Research and Advanced Studies in Education”, in German “Society for educational factual research and advanced educational studies e. V. ”, which is now known as the“ Society for the Promotion of Educational Research e. V. (GFPF) ”. This company was founded on March 27, 1950 in Wiesbaden. Its founding members included government directors and ministerial directors, but above all Erwin Stein, Erich Hylla and Franz Hilker , who founded the "Pedagogical Workplace" in Wiesbaden in 1947 as a pedagogical documentation center. At the founding meeting of the company, Erwin Stein was elected President and Erich Hylla was introduced to the management. The company's articles of association state:

"The purpose of the company is to maintain and promote pedagogical factual research and its utilization for all areas of education, including school supervision and school administration, in particular for the pedagogical further training of teachers of all types of schools."

It is obvious that this purpose of the association is very close to what Hylla has described as the task of educational research , and for how this purpose of the association is to be achieved the bonds with him cannot be overlooked. One point is particularly striking: "Promotion of the establishment and work of an institute for educational factual research and for the further training of teachers in this field." Behind this formulation hides a departure from Hylla's earlier ideas, in which he still worked for research institutes Universities as the focal points of the pedagogical faculties there. Hylla justified this about-face in his contribution "A College for International Research", which he held on November 16, 1950 at the founding event for the College for International Educational Research . He first repeats his criticism of university educational research and then continues:

“A supplement on the side that I would like to call pedagogical factual research seems to me urgently necessary. The pedagogical institutes or universities , which serve almost exclusively the preparatory training of elementary school teachers and vocational school teachers, can also pay little attention to research due to lack of time and money and due to their overload with teaching tasks. "

He adds a further argument to this need for an institute of its own, owing to the inability of the traditional universities and the practical constraints to which teacher training institutions are subject, the need to teach educational research. “In this sense, the institute will also be a school for educational research and thus, in the true sense of the word, a university.” With this last point, Hylla again approaches Fritz Karsen's basic ideas for the German Research University, where educational research would have an important role should play.

In 1952, Hylla describes the founding act of the institute, which was now established as a university of its own, as follows in the university's first brochure:

“The establishment of the university took place on November 16, 1950. It was initially sponsored by a group of Hessian schoolmen interested in educational research, which in the spring of 1950 established itself as a 'Society for educational factual research and advanced educational studies' in Wiesbaden with Dr. Stein had constituted as president and the author as managing director. At the request of the Society, the Hessian Cabinet agreed to maintain the university as a permanent establishment and to grant an amount of 200,000 DM each for the first two years in which considerable Amenkan funds were still available or prospective for its operation . In March 1951, a preparatory department of the university was set up in Frankfurt, and work on restoring and redesigning the building in Schloßstraße could begin in the summer. "

The establishment of the "University for International Educational Research", from which the German Institute for International Educational Research (DIPF) later emerged, was thus completed. The DIPF is now a member of the Leibniz Association and is available as Blue List Institute in the tradition of state agreements on the Königsteiner country agreements attributed to the German Research Academy . Wrinkle also recalls this line of tradition, citing his diary entry from August 19, 1949 on the occasion of Erwin Stein's 65th birthday: “Spent nuch time today talking with Prof. Hylla about an Institute for Educational Research, Stein's proposal, Fritz Karsen's plan, Etc."

The institutionalization of the university

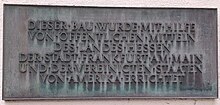

At the badly damaged building in Schloßstr. 29 in Frankfurt-Bockenheim, which Hylla already mentioned above, the war damage was repaired in 1951/1952 and the building was prepared for the institute's purposes. Frank H. Jonas describes the related work and expenses:

"Heinrich Seliger, Frankfurt city superintendent of schools, assisted the group [Stein, Hylla, Wrinkle] in search of a building. The city donated a bomb-damaged, five-story building, with an adjoining gymnasium, which had formerly been an elementary school. At the time the building and site were valued at DM 1,200,000 ($ 285,600). The State of Hesse agreed to maintain the Institute permanently and to date has made two appropriations totaling DM 400,000 ($ 95,200) for operating expenses. IN AUGUST, 1950, a grant of DM 800,000 ($ 190,400) was made from the HICOG Special Projects Fund for the reconstruction and adaption of the building and in January, 1951, another grant of DM 336,000 ($ 79,968) was made for operations and equipment. Later, as building costs rose, the city of Frankfurt donated DM 150,000 ($ 35,700), matched by a like further amount from the HICOG Special Projects Fund. Had not an old building been reconstructed, the building costs would have been three times as high. In November, 1951, a HICOG grant of DM 177,000 ($ 42,126) was approved for equipment and operations.

The building, now fully equipped, is a monument to joint American and German efforts to encourage research in specific educational fields that have been neglected and undeveloped, not only because of a totalitarian regime and a devastating war, which sealed off Germany from the rest of the Western world for more than a decade, but also because of the resistance of traditional outlooks and procedures the physical properties of the new institution are modern and complete. "

In addition to the necessary lecture halls, library, work and administration rooms, the building also contained 28 apartments for students and some apartments for professors. The former gymnasium has been transformed into an auditorium with around 240 seats. Compared to most universities, the new university was “not a state institution, but an independent, legally responsible foundation under public law. Its headquarters are in Frankfurt am Main. Like all foundations under public law, it is under state supervision, which is led by the Hessian Minister for Education and Popular Education, but is limited to monitoring compliance with laws, other legal provisions and the statutes. Freedom of research and teaching, which of course does not release the university from loyalty to the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, is expressly guaranteed in the statutes. ”The purpose of the foundation was to promote international educational research.

The organs of the university were the board of directors and a board of trustees, “which should give general guidelines for the work of the university, determine the budget, monitor its observance and approve proposals of the board about the appointment of members of the research and teaching body. [..] The board includes the director of the university as chairman, the president of the board of trustees as a deputy, as well as the treasurer and the secretary of the board of trustees. He is responsible for the general administration of the university. ”In contrast to state universities, the director was appointed for an indefinite period. The composition of the teaching staff and their qualifications corresponded to university standards.

The special character of the new university manifests itself above all in the description of those who are to study at it:

“As a student, according to the statutes, the university will accept teachers of all types of schools for at least one year, as well as officials and employees of the school administration - including women of course - after completing their vocational training and sufficient practical experience. In principle, the university entrance qualification is required for students. In accordance with the primary tasks of the university - to maintain pedagogical research - this course will primarily consist of conducting research work under suitable supervision. Of course, this does not exclude that lectures are also heard and exercises carried out that are suitable for promoting this research work. A formal diploma was not provided for the graduates: “A final exam, a diploma or the like is not considered. An examination would not correspond to the type of work planned. Work that emerges from the university's research should be published in a suitable manner under the name of its author. '"

This target group should “be given leave of absence from their departments, if necessary, leaving their salary unchanged, and receive a monthly allowance from the funds available to the university, from which the modest costs for living space in the university building and the additional costs for the Can essentially cover livelihoods outside of their place of residence. "

The areas of work described in the prospectus correspond to what has been postulated earlier, based on Hylla's above-cited article Tasks in educational research . Nevertheless, it is interesting to note what is already being presented as ongoing and planned work by Hylla at this early stage:

“The small office is busy with the preparatory work, especially with the construction of the library, the problems of building the house and the procurement of the equipment. Nevertheless, a number of scientific works are already underway. Among them is the publication of a presentation of the youth education system in ten important countries in Western Europe, for which an excellent expert from each country made a contribution after a contribution by Dr. WL Wrinkle and the author provided a carefully crafted, uniform plan. Some German adaptations of valuable foreign books on educational psychology are already in print. We hope that the university will be able to distribute a considerable number of these books to educational institutes, university and study seminars, teacher training centers, teachers' working groups and similar institutions on request against reimbursement of packaging and shipping costs. [..] The development of a test program for schools has already started. In August last year, an invitation conference was held by West German test authors to find out what work is in progress in this area and what the university could do to promote it. In January, Professor Dr. Victor Noll, Lansing, Michigan, with input from Dr. W. Glassey, Croydon, England, and Professor Dr. Meili , Bern, carried out a two-week working group for test research. If conditions permit, a four-week study group on educational psychology abroad will take place in August, in which numerous European and American experts will take part, and which is primarily intended for representatives of educational psychology at West German universities, colleges of education and similar institutes . We hope that the university will be able to cover the living expenses of the teachers and the participants. "

The first years in retrospect

"On April 1, 1953, the University for International Educational Research, Frankfurt / Main, started its work with three professors, two assistants and 20 student employees." This first academic year ended on March 18, 1954 with a meeting of the Students together with members of the research and teaching staff. Erich Hylla gave a speech on this occasion, in which he was very pessimistic about the social acceptance of education in the Federal Republic of Germany and the state of the educational system. He speaks of a permanent crisis for which the era of National Socialism alone cannot be held responsible, and asks:

“Why this plethora of conflicting and conflicting opinions, desires and goals? Why is it not possible, for example, to come to a school law in our country, which may not please everyone in its details, but which on the whole is approved by all parties - as was possible in England? Why can't we in Germany develop a school reform plan that meets with such general approval, such as the Swedish one that has been in place since 1950? "

He names four reasons for this:

- The missing or lost "belief in the effectiveness, perhaps, of conscious and planned education in general, but in any case of school education". This results in a largely lack of public interest in school, education and upbringing issues. (P. 52)

- "As a people and as individuals, we are not prepared to sacrifice an appropriate part of the national product, our national and also our individual income, for education." (P. 53)

- "We have little inclination to grant freedom for experiments , for practical testing of new ways and to approve the necessary funds." (Pp. 53–54)

- As the fourth cause, “which, by the way, has an effect not only in the educational field but also in other areas of life”, he states the fact “that the state is expanding its influence more and more, and that this influence is essentially leveling out. Also from others, e.g. B. on the ecclesiastical side recently referred to this development with justified concern. In part, it is connected with the fact that our pursuit of justice for all easily into such by egalitarianism degenerated that, for the field of education. B. the private initiative and the willingness to make personal expenditures, for example for private and better than average equipped schools, are not welcomed or even prevented because not all children can enjoy their advantages. "(Pp. 54-55)

It is difficult to understand this last point as pessimism. It clearly resonates with a criticism of social democratic educational policy. An understanding of the state is articulated, the closely aligned on liberal thought patterns and with the term egalitarianism sanctioned a criticism pattern that after the war against the comprehensive school was mobilized and sixty years later still against the comprehensive school .

Hylla asks himself what his four points have to do with the graduates of the first year of university and the task of the university. His answer: “Crucial. Pedagogical research can contribute significantly to clarifying the situation in the field of education, to unraveling confusion, to proving false generalizations from isolated experiences, such as those often arising from wishes and prejudices, as such, and to providing documents for factual decisions. In this way, it can help to overcome the four main causes (and perhaps also some others) set out above for the unpleasant and critical overall situation in our German education system. "(P. 55)

Just as he described above pedagogical-psychological tests as quasi-neutral instruments that automatically provide reliable knowledge, here, too, pedagogical research is described as apparently lacking in interest, which in itself produces “pure” truth. In Jürgen Habermas' definition, he is talking about a technical interest in knowledge that pretends to be disinterested and objective and thereby denies or does not reflect his own previous interest in knowledge. Already his fourth point of criticism already includes a massive prior knowledge-guiding interest that is legitimate, but therefore by no means “scientifically objective”.

Nonetheless, Hylla is certain that "the right direction has been taken" and that the university was able to present itself to its students "primarily not [as] a teaching institution, but [as] a research institute" (p. 56). His verdict on the work done so far is:

“'We have made a start.' That may seem like little. But when you keep in mind how new our company is, when you consider how many decades it has taken research in other more easily accessible areas, such as science and technology, biology and medicine, to develop To develop what it is today, we can also be content with it, if we can only assume that the first steps that we have taken have been taken in the right direction. (P. 58) "

Fourteen years later, on Erich Hylla's 80th birthday, Walter Schultze , who was appointed professor at the university in 1952 , looks back positively on the early years.

“At that time we were a small group, the university was an unknown institution, which at its opening conference enjoyed the best wishes of numerous representatives of national and international pedagogy, but was not considered by all to be a very strong and viable child. Today we look back on fourteen years of work and, despite all the bad prognoses, have developed into an institute that is not only known, but also recognized, within and outside of Germany, from kindergartens to colleges and universities. [..] What courage, but also what almost dreamlike security must have moved Professor Hylla at that time, at an age when other people have already retired, to tackle such a task again and with such a small group of active employees Not only to raise the claim of a scientific university and research institute, but also to realize it. "

Erich Hylla retired on March 31, 1956, but remained closely associated with the University for International Educational Research . He died on November 5, 1976 in Frankfurt am Main.

After his death, his daughter, Gudrun Hylla, donated the Erich Hylla Prize , endowed with 3,000 euros . The prize is awarded every three years by the German Institute for International Educational Research together with the Society for the Promotion of Educational Research to personalities or institutions who have made a contribution to education, science or upbringing in research or practice.

Erich Hylla honors

- 1956: Cross of Merit 1st Class of the Federal Republic of Germany

- 1956: Goethe badge (Hessian Ministry for Science and Art)

- 1959: Plaque of honor from the city of Frankfurt am Main

- 1967: Great Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

literature

- Bärbel Holtz (edit / ed.): The minutes of the Prussian State Ministry 1925–1938 / 38. Vol. 12 / II. (1925-1938) . Olms-Weidmann, Hildesheim 2004. ISBN 3-487-12704-0 ( Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences [Hrsg.]: Acta Borussica . New series .)

- Werner Correll and Fritz Süllwold (eds.): Research and education. Studies on problems in pedagogy and pedagogical psychology. Festschrift for the 80th birthday of Erich Hylla. Publishing house Ludwig Auer, Donauwörth, 1968.

- Erich Hylla on his 80th birthday , published by the German Institute for International Educational Research and the Society for the Promotion of Educational Research e. V. , Frankfurt am Main, 1967

- Bernd Frommelt and Marc Rittberger: GFPF & DIPF. Documentation of a cooperation since 1950 , materials for educational research, Volume 26, Frankfurt am Main, 2010, ISBN 978-3-923638-44-4 . The volume is available online at GFPF & DIPF. Documentation of a cooperation since 1950

- Uwe Wolfradt, Elfriede Billmann-Mahecha, Armin Stock (eds.): German-speaking psychologists 1933 - 1945. An encyclopedia of persons, supplemented by a text by Erich Stern , Springer, Wiesbaden, 2015, ISBN 978-3-658-01480-3

Web links

- Literature by and about Erich Hylla in the catalog of the German National Library

- Erich Hylla in the WorldCat Overview

- Frank H. Jonas: Educational Research in Germany

- Jürgen Oelkers: Script for the lecture Pragmatism , WS 2006/2007

- 60 years "Society for educational factual research and further educational studies" (today: GFPF)

- The Erich Hylla Prize

Individual evidence

- ↑ This and all other biographical information is, unless otherwise stated, the "biographical notes" in the appendix to Werner Correll and Fritz Süllwold (eds.): Research and Education. Studies on problems in pedagogy and pedagogical psychology. , Pp. 235-236.

- ↑ Karl Bungardt: Erich Hylla, teacher of teachers , in: Erich Hylla for his 80th birthday , p. 14

- ↑ Karl Bungardt: Erich Hylla, Lehrer der Lehrer , in: Erich Hylla zum 80th Birthday , p. 15. The Bobertag mentioned in the quote is Otto Ulrich Bobertag (* February 22nd, 1879 - † April 25th . 1934), a former research assistant to William Stern and later head of the test psychology department at the Central Institute for Education . He probably committed suicide out of fear of the Nazis. (Uwe Wolfradt: Bobertag, Otto . In: Uwe Wolfradt, Elfriede Billmann-Mahecha, Armin Stock (ed.): German-speaking psychologists 1933-1945 , pp. 40-41). Frank H. Jonas points out the importance of the tests adapted by Hylla and Bobertag, although he focuses on Hylla: “His Intelligence Testing, published in 1927, is still recognized as a standard work. Aptitude and achievement tests, developed in 1926 and 1932 in collaboration with Dr. Otto Bobertag. were republished in 1945 and subsequently used in 70,000 cases in the state of Hesse. "( Frank H. Jonas: Educational Research in Germany )

- ↑ For Richard Thomas Alexander see the article in the English Wikipedia: en: Richard Thomas Alexander .

- ^ "As the educational systems began functioning along older lines, E&RA strength rose to forty officials by mid-1946. Because of its lowly status within the military government, E&RA was unable to attract a prominent American education expert to lead it. Military Governor Lucius D. Clay was, therefore, forced to appoint his unknown section chief, John W. Taylor, who had a doctorate in education from Columbia Teachers College. Taylor then enlisted his old mentor, Richard Thomas Alexander, as his adviser. Both were well acquainted with prewar German education. An outspoken critic of the traditional multitrack system, Alexander enlisted German reformers, such as the Prussian education expert Erich Hylla, in his cause. "(Detlef Junker (ed.): The United States and Germany in the era of the Cold War , p 396.) The E&RA, the "Education and Religious Affairs Section", is a department of OMGUS that was headed by Taylor until spring 1947, then by Alexander. (Johannes Weyer: West German Sociology, 1945-1960. German Continuities and North American Influence , Duncker & Humblot, Berlin, 1984, ISBN 9783428056798 , p. 329) For this change from Taylor to Alexander see also: victims of circumstances , Der SPIEGEL, 14 March 1983.

- ↑ Erwin Stein : Greetings , in: Erich Hylla zum 80th Birthday , p. 8. In 1927 Fritz Karsen was also granted a study visit to the USA, also at the invitation of Richard Thomas Alexander. Through his assistant at the time, the previously mentioned John Taylor, Karsen was appointed Chief, Higher Education and Teacher Training in the Education and Cultural Relations department of OMGUS in 1946 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Werth: The teaching of theory and practice at the Prussian Pedagogical Academies 1926-1933 - illustrated using the example of the Pedagogical Academy Halle / Saale (1930-1933) dipa, Frankfurt am Main, 1985, ISBN 978-3-7638-0805- 2

- ↑ a b c d Oelkers: Script for the lecture Pragmatismus , WS 2006/2007, p. 4-5 & p. 18ff. What Jürgen Oelkers claimed several times is clearly wrong: “HYLLA was dismissed from the Prussian civil service in 1933 and emigrated to the United States, where he held various visiting professorships. He returned immediately after the end of the war. "

- ↑ a b c d e Frank H. Jonas: Educational Research in Germany

- ↑ Uwe Wolfradt: Hylla, Erich . in: Uwe Wolfradt, Elfriede Billmann-Mahecha, Armin Stock (eds.): German-speaking psychologists 1933–1945 , pp. 204–205

- ↑ Erwin Stein (Richter) : Greetings , in: Erich Hylla for his 80th birthday , p. 9

- ↑ Erwin Stein (Richter) : Greetings , in: Erich Hylla for his 80th birthday , p. 9

- ↑ Detlef Junker (ed.): The United States and Germany in the era of the Cold War , p. 396. The E&RA, the "Education and Religious Affairs Section", is a department of the OMGUS that is open until spring 1947 was directed by Taylor, then by Alexander. Johannes Weyer: West German Sociology, 1945-1960. German continuities and North American influence , Duncker & Humblot, Berlin, 1984, ISBN 9783428056798 , p. 329

- ^ Gerd Radde: Fritz Karsen: a Berlin school reformer from the Weimar period . Berlin 1973. Extended new edition. With a report about Sonja Petra Karsen's father (= studies on educational reform, 37). Frankfurt a. M. [u. a.] 1999, ISBN 3-631-34896-7 , p. 211

- ^ Inga Meiser: Die Deutsche Forschungshochschule (1947-1953) , publications from the archive of the Max Planck Society, Volume 23, Berlin, 2013, ISBN 978-3-927579-27-9 . The study is the revised version of a dissertation submitted in 2010; it is available online at Inga Meiser: Die Deutsche Forschungshochschule , p. 40

- ↑ Bernd Frommelt and Marc Rittberger: GFPF & DIPF. Documentation of a cooperation since 1950 , p. 11

- ↑ Erwin Stein (Richter) : Greetings , in: Erich Hylla for his 80th birthday , pp. 9-10

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Erich Hylla: Tasks of educational research , in: Bernd Frommelt and Marc Rittberger: GFPF & DIPF. Documentation of a cooperation since 1950 , pp. 15–24

- ↑ Big Brother Awards 2006 - Ministers of Culture and the Interior cleared Spiegel Online from October 20, 2006

- ↑ Bernd Frommelt and Marc Rittberger: GFPF & DIPF , p. 13

- ↑ Franz Hilker was also the editor of the magazine Bildung und Erziehung , in which the announcements of the new university were to be published in the future.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Erich Hylla: The University for International Educational Research - The first institute prospectus (1952) ( Memento of the original dated November 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Bernd Frommelt and Marc Rittberger: GFPF & DIPF , pp. 25–26

- ↑ Bernd Frommelt and Marc Rittberger: GFPF & DIPF , p. 27

- ↑ Bernd Frommelt and Marc Rittberger: GFPF & DIPF , p. 27

- ↑ Bernd Frommelt and Marc Rittberger: GFPF & DIPF , p. 27

- ↑ Bernd Frommelt and Marc Rittberger: GFPF & DIPF , p. 39

- ↑ 60 years of "Society for educational factual research and advanced educational studies" (today: GFPF) ( Memento of the original from November 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , P. 1

- ↑ Bernd Frommelt and Marc Rittberger: GFPF & DIPF , p. 67

- ↑ Dr. Victor Noll: “Dr. Noll was a Professor in the Department of Counseling, Personnel Services and Educational Psychology from 1938 to 1966. Dr. Noll earned his BS from Pennsylvania State University in 1922. He worked as a high school science teacher for three years in Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania before earning his MA and Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota. Prior to joining the faculty at MSU, Dr. Noll worked as a research associate at Columbia University's Teachers College from 1932-1934 and as professor and head of the Psychology Department at Rhode Island State College from 1934-1938. "( Victor H. and Rachel P. Noll Scholarship )

- ↑ To Dr. W. Glassey only finds a note in WorldCat: W Glassey and EJ Weeks: The educational development of children. The teacher's guide to the keeping of school records , University of London Press, London ;, 1950 ( W. Glassey in WorlCat

- ↑ a b Walter Schultze : Erich Hylla for his 80th birthday , in: Erich Hylla for his 80th birthday , published by the German Institute for International Educational Research and the Society for the Promotion of Educational Research e. V. , Frankfurt am Main, 1967, pp. 21-24

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Erich Hylla: Completion of the first year of study , in: Bernd Frommelt and Marc Rittberger: GFPF & DIPF. Documentation of a cooperation since 1950 , materials for educational research, Volume 26, Frankfurt am Main, 2010, ISBN 978-3-923638-44-4 . The volume is available online at GFPF & DIPF. Documentation of a cooperation since 1950 , pp. 51–58.

- ↑ Compare this: No integrated comprehensive school in Niederrad, Frankfurter Rundschau from November 1, 2016

- ↑ Erich Hylla Prize

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hylla, Erich |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German educator |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 9, 1887 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Wroclaw |

| DATE OF DEATH | 5th November 1976 |

| Place of death | Frankfurt am Main |