Franz Stollwerck

Franz Stollwerck (born June 5, 1815 in Cologne ; † March 10, 1876 ibid) was a German industrialist whose group of chocolate products gained worldwide recognition. The family dynasty included his five sons, who continued to expand the company.

Career

Franz was born in Cologne in 1815 as the fourth son of the wool spinner Nikolaus Stollwerck (1787–1851) and the brewer's daughter Christina Boden (1784–1837). He grew up in his parents' house on Wallonengasse No. 53, a street that after 1813 again had the old (since 1268) name Löhrgasse and which was later given its current name as Agrippastraße.

Franz did an apprenticeship with the Cologne confectioner Franz Josef Kreuer and, following the old artisan tradition, set out early on to travel to foreign training centers. He attended the high schools of sugar confectionery production in Württemberg , Switzerland and finally in Paris, where the young Stollwerck learned his trade as a traveling companion. With knowledge and new skills he returned to Cologne around 1838.

On July 3, 1839, he married Anna Sophia Müller. The marriage resulted in 13 children, of which he initially took his three sons Albert Nicolaus (1840–1883), Peter-Josef (1842–1906) and Heinrich (1843–1915) into his company. They were later followed by Ludwig (1857–1922) and Carl Franz (1859–1932).

The trained baker and master confectioner Stollwerck founded a “shortbread bakery” in Cologne's Blindgasse 37 (today: Cäcilienstraße) in July 1839, whose product range he continuously expanded to include confectionery, Christmas tree hangings, marzipan and chocolates. Three years later he bought the property and house at Blindgasse 12, where he built his "confectionery and candy factory" on a 120 m² floor space. At first he did not become famous with these products, but from July 1843 with the production of cough drops. His sales success led to a legal dispute with the pharmacists who reserved the production of cough drops as medicines and remedies. After numerous trials, he obtained the ministerial decree of January 2, 1846, according to which "the confectioners of the entire Prussian state are not barred from making and selling caramels, sweets and other goods." The bestseller "Breast Sweets" made him so famous and wealthy, that people in the Rhineland spoke fondly of the "Camelle Napoleon". He advertised intensively in newspapers and medical journals and built up an extensive sales network. In 1845 Stollwerck already had 44 sales outlets in Germany; in January 1847 he received the title of "purveyor to the court of Prince Friedrich of Prussia". In December 1847 he founded the Café Royal ( Schildergasse 49), which sold its chocolate and confectionery, and on 1 April 1848, the course of the March Revolution in German cafe has been renamed. It was a mixture of a coffee shop, a pastry shop and a wine bar with a ballroom. However, his business went bad after that, because in May 1853 the Cologne commercial court confirmed his bankruptcy with "fallit". As early as 1856 he opened the “Königshalle” (2,400 seats; Bayenstrasse), the largest restaurant in Cologne.

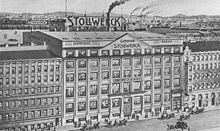

At the World Exhibition in Paris in 1855 he was the only German exhibitor to receive a medal for his breast sweets. In 1864 his sweets were so famous that they could be bought in 900 shops in German and many European cities. Chocolate production did not come to the fore until 1860. The chocolate was produced industrially in the factory at Hochstrasse 9a and 164 (later Hohe Strasse ), which was expanded in 1866 . In 1863 Franz Stollwerck offered the Königshalle to the city of Cologne for purchase, but the city council rejected the purchase in a secret meeting on September 24, 1863. In the rooms of the Ballhaus, candy and liqueur production was then taken up on a larger scale. After their technical or commercial training and a happy return from the German War of 1866, his five sons pressed for a share in his flourishing company. On December 16, 1868 a partnership agreement legalized the participation of the three sons Albert Nikolaus, Peter Joseph and Heinrich. Their participation led to the name being changed to "Franz Stollwerck & Söhne GmbH". The product range now comprised 375 types of chocolate. Immediately there were conflicts between the father and his sons. On May 7th, 1870, the oldest, Albert Nikolaus (called Nicolas) Stollwerck, left the company and founded the sugar processing factory “Steam, Sugar, Cutting, Glaze and Poudre Raffinade” in Corneliusstraße 12. Almost two years later he was followed by his Brothers Heinrich and Peter Joseph, and on January 1, 1872 the company "Gebrüder Stollwerck" was entered as a general partnership in the Cologne commercial register, which the younger brothers Ludwig and Carl also joined a few years later. The company headquarters were located at Brückenstrasse 12, while production was located on Corneliusstrasse and Annostrasse. The large factory on over 55,000 square meters was called "Kamelle-Dom" in Cologne. Shortly before his father's death in 1876, the two Stollwerck companies were merged into one, which had been operating under the name "Kaiserlich-Königliche Hof-Chocoladen-Fabrik Gebr. Stollwerck" since May 1, 1874. On November 29, 1887, the Stollwerck company was appointed purveyor to the Queen's court. The number of employees of the Stollwerck brothers rose from 325 employees (1876) to 2,000 in 1890.

Sons

His five sons (Albert Nicolaus, Peter Joseph, Heinrich, Ludwig and Carl) were all involved in the chocolate business. Albert Nikolaus (born November 28, 1840 in Cologne, † April 4, 1883 in Jerusalem) was in charge of finances and organization in his father's factory. He also operated his own machine agencies, dealt with sugar wholesaling, the production of lump sugar, powdered sugar and icing sugar and the manufacture of Emser and Kissinger pastilles. He later received power of attorney and took over purchasing, costing, correspondence and general sales organization. He was the initiator and co-founder of the Association of German Chocolate Manufacturers and inventor of the first quality seal for chocolate.

Peter-Joseph (born March 22, 1842 in Cologne, † March 17, 1906 in Bonn) was initially a traveler for his father's company and then headed the detailed field service. Later he introduced a modern bookkeeping and accounting system and took over the management of finances and personnel.

Heinrich (born October 27, 1843 in Cologne, † May 9, 1915 in Cologne) completed his technical training against the express will of his father and with the financial support of his brother Albert Nikolaus. He took over the management of the new factory in Hohestrasse and constructed numerous new systems there. In 1872 he set up his own design department in the company, which already covered most of the company's own needs in 1875 and whose machines were sold worldwide. The ingenious technician and inventor, for example, doubled the production capacity of chocolate with his invention of the 5-roller mill patented in 1873. He fell victim to a classic industrial accident in 1915 when he got caught in a mixer he had invented and succumbed to his injuries.

Ludwig Stollwerck (born January 22, 1857 in Cologne, † March 12, 1922 in Cologne) was incorporated into the field service of the family business in 1879 by his brother Albert Nikolaus. He was very open to new developments that he could use to market the products. As early as 1879, he made his own showcases, display boxes and presentation aids available to resellers for shops, buffets and other locations, and set up the “Stollwerck boxes and cardboard factories” which produced hundreds of packaging forms. After Nikolaus Stollwerck died in an accident during a pilgrimage, he took over the management of sales in 1883. Inspired by a study trip to America, in 1887 he implemented the idea of filling vending machines with samples and chocolate. In 1893, 15,000 machines were installed in Germany, in 1894 there were 4,000 machines in New York alone. The origin of the vending machines in Germany goes back to Stollwerck. In 1895 he founded the company Deutsche Automaten-Gesellschaft Stollwerck & Co specifically for this purpose . The vending machine business in the chocolate sector was going well, because until 1914 the chocolate vending machines were the market leader in the USA. This encouraged Ludwig to conclude contracts with people outside the industry, for example with a French perfume company. Fragrance dispensing machines subsequently became very popular in Germany.

Ludwig Stollwerck was appointed chairman of the supervisory board of the German companies Diamant , Deutsche Zündholzfabrik and Deutsche Sunlight . In March 1896 he acquired the German license for the Cinématographe Lumière . On May 23, 1896, three short films were shown as German premieres in Cologne at Pentecost, because the Deutsche Automaten-Gesellschaft had acquired the exploitation rights for all of Germany. Just a few months later, over a million viewers had watched Stollwerck's Living Photographs . Ludwig remained loyal to the company until his death in 1922.

Carl (born November 6, 1859 in Cologne; † October 3, 1932 in Feldkirchen), the youngest of the brothers, lived and worked in the shadow of his brothers. Shortly after his marriage in 1885, at the request of his wife, he moved his residence from Cologne to the Giglberger Hof near Feldkirchen in Bavaria, which he expanded into the " Hohenfried " mansion . After the death of his brothers, he ran the company from 1922 together with his nephews Gustav (* May 7, 1872 in Cologne; † October 13, 1951 in Vienna), Franz (* May 20, 1877 in Cologne; † June 5, 1955 in Obertshausen), Fritz (born July 4, 1884 in Cologne; † December 6, 1959 in Bad Godesberg) and the directors Trimborn, Harnisch, Eppler and Lute.

The industrial group

With a contract dated December 16, 1868, the three eldest sons Albert Nikolaus (1840–1883), Peter Josef (1842–1906) and Heinrich (1843–1915) joined the father's company, which was renamed “Franz Stollwerck & Sons” .

In 1871 his five sons founded the Stollwerck brothers , which were entered in the Cologne commercial register on January 1, 1872. The company headquarters was moved to Brückenstraße 12, production was located in Cornelius- and Annostraße. While both companies cooperate externally, the disputes smoldered internally until the death of Franz Stollwerck in 1876. After that, the sons merge the two companies. They call the new company “Königl. Prussia. and Kaiserl. Oesterr. Hof-Chokoladefabrikanten Gebrüder Stollwerck ”and marketed their products with increasing success.

In addition to the main products, chocolate bars and cocoa powder, the factories produce a total of 375 chocolate products, 150 different types of chocolate, fruit and herb sweets, 80 types of cakes, as well as waffles, marzipan and many other confectionery products. The large factory on over 55,000 square meters is called "Kamelle-Dom" in Cologne. The brothers took over the sugar company from Nikolaus as well as the "Magazin der Emser Felsenquellen" and opened the first shop in the same year at Brückenstraße 12.

The capital available to the brothers amounted to about 72,500 thalers. The largest part came from dowries and private assets, 4,000 thalers were borrowed. In mid-May 1872, around 15,000 thalers were booked for buildings and facilities, 5,500 thalers for setting up the store, 6,000 thalers for supplies, 5,500 thalers for shipping materials, 4,500 thalers for raw material supplies, 4,000 thalers for the bonded warehouse, 5,000 thalers for customs deposits. The young company had outstanding balances of 30,500 thalers and 1,500 thalers in cash.

Their enthusiasm for innovation brought them numerous patents, such as for fizzy lemonade sugar or manufacturing processes for acorn cocoa (October 4, 1881) or the patent certificate for the steam roaster for cocoa from February 5, 1889.

The first "factory depot of the KuK Hofchocoladenfabrik Gebr. Stollwerck" was established in Vienna in 1873. The factory depot was later expanded into a branch. In 1877 Stollwerck opened the "Engrosniederlage Berlin", to which a detailed sales point was attached. Further branches followed with Berlin (1886), Pressburg / Bratislava (1896), London (1903), Stamford / USA (1905, expropriated 1918) and Kronstadt / Braşov in Transylvania (1922). In 1887 Ludwig Stollwerck had the first vending machines installed in Germany. From this a new sales channel developed in a few years, with which Stollwerck had already generated a fifth of sales in 1891.

One sensation after another followed. In 1888 reports went around the world about the “Stollwerck Chocolate Temple”, which Ludwig Stollwerck had built from 7,800 kg of chocolate for the international competition in Brussels. In 1889 Stollwerck reported the employment of 1,696 workers. In 1890, Stollwerck started production in the so-called "export factory", which was built specifically for the reimbursement of customs duties on exports. In 1891 the press reported on the complete electrification of the Cologne plant and the use of 600 incandescent and 40 arc lamps. In 1892 drive machines with a total of 650 hp were in operation at the Cologne plant. In 1893, Stollwerck produced the first enamel signs as "advertising posters using the icing process" at Schulze & Wehrmann in Elberfeld, the first industrial enamelling plant for advertising signs in Germany. In 1894 Ludwig Stollwerck and his US business partner John Volkmann founded their own machine production for the USA.

In 1895 Ludwig Stollwerck outsourced the machine business and founded the "Deutsche Automaten Gesellschaft" (DAG). In 1896 the Stollwerck-Verlag had produced more than 50 million collector's pictures . On March 26, 1896, Stollwerck acquired the German license for the cinematograph from the Lumière brothers in favor of his DAG, so that on April 20, 1896, the first German film screenings took place in Cologne (Augustinerplatz). In 1897 the New York Customs Office reported that Stollwerck alone produced more chocolate than all European countries combined. In 1898 Stollwerck opened one of the first vending machine restaurants in Germany. In 1899 Ludwig and Heinrich Stollwerck were awarded the title of imperial and royal purveyors to the court of Vienna . In 1900 there was a shortage of workers in Cologne, and Stollwerck built six residential buildings as an attraction, where well-earned Stollwerck workers found an apartment for a minimal rent. 1901 Ludwig Stollwerck provided the basis for the founding of the American Stollwerck Brothers Ltd .

The expansion required the conversion into an AG on July 17, 1902, which, however, did not go public until 1923. In addition to the bearer shares , a total of 5,000 preference shares at 1,000 marks were issued on July 17, 1902 , most of which were taken over by the house banks . This is how Deutsche Bank became a shareholder. 1903 brought Stollwerck with the collaboration of Thomas Alva Edison , the speaker of chocolate on the market, a phonograph with chocolate record. Was uneconomical as the export to England by constantly increasing tariffs, Ludwig Stollwerck decided in 1903 establishing the English factory Stollwerck Brothers Ltd . in London's Nile Street . As part of the modernization of the company, Peter Joseph Stollwerck and Ludwig Stollwerck founded "Kölnische Hausrenten AG" in 1904 to build the Stollwerckhaus in Hohe Strasse. The luxurious building had a shopping arcade for the first time in Germany and gave passers-by on the ground floor an insight into the ongoing chocolate production. From 1905 to 1907 Stollwerck built the new Stollwerck Brothers, Inc chocolate factory . in Stamford, USA. In 1906 "Alpia" was registered as a brand name. In 1907 the house banks forced Stollwerck to make a further capital increase, and a further 7,000 preference shares at 1,000 marks were issued. Ludwig Stollwerck was very concerned about the increasing influence of the banks on the company. In the same year he converted the “KuK Hofchocoladenfabrik Gebr. Stollwerck” in Preßburg into the “Gebrüder Stollwerck AG Preßburg” with a capital of three million crowns. Due to the increasing shortage of labor in Preßburg, Stollwerck decided in 1909 to set up another factory in Vienna, where 360 employees had found work by the outbreak of war. The Cologne family business had meanwhile become a company with global renown. In 1912 Stollwerck had over 5,600 employees and claimed to be "the largest chocolate, cocoa and sugar confectionery company in the world".

The First World War initially brought profits for the troops due to the high nutritional value of chocolate, but then large losses. From 1916 sugar was rationed and the difficulties with importing cocoa increased. The British government imposed an economic blockade on the Central Powers, which cut off Germany from foreign markets. Although the resulting oversupply of sugar had a positive effect on sugar prices for Stollwerck, the most important raw material, cocoa, could hardly be obtained. In 1914 the branch in Amsterdam and the branch in London were closed. In the same year one of Cologne's house banks, A. Schaaffhausen'scher Bankverein AG, was taken over by Disconto-Gesellschaft in Berlin, which later turned into a fatal situation for Stollwerck. Heinrich Stollwerck died in 1915 as a result of an explosion in a fondant kettle and left a huge gap in the company in the development of production machines. At the end of 1916, the production of all chocolate products except the “Gold” brand had to be temporarily stopped because there were hardly any raw materials left. The amount of raw cocoa processed had fallen from 3,165 tons a year to 228 tons. The American company was confiscated and auctioned after the USA entered the war. Compensation was not paid until 1928.

Nevertheless, the Stollwerck brothers managed with prudence and strategy to prevent the complete decline of the company. From 1916 on, Stollwerck offered to carry out external orders in his subsidiary companies, equipped with the most modern machines, the sheet metal and can factory, joinery and box factory, cardboard packaging, book printing and embossing department. Stollwerck rented the mechanical engineering and the punching plant to the Cologne-based company Pelzer & Co. , which produced cartridge magazines for the War Ministry. In collaboration with the Berlin chemist Dr. Michaelis, Stollwerck developed the new product "Nurso" to ensure the nutrition of the population. In “Nurso” the cocoa substance was replaced by prepared carbohydrates with the addition of vanillin . In order to improve the nutritional situation of its own employees, Stollwerck procured special contingents for the production of jam, which was given to the workforce at factory prices.

Ludwig Stollwerck found various solutions for the supply of cocoa, which he called “tricks”: “Our Dutch friends sent lots from Holland to Switzerland via Mannheim, - and during the water transport Rotterdam-Mannheim the goods were sent to a German company by the Switzerland and the latter gave the Mannheim freight forwarder the order to send the goods to the new buyer in Germany. ”When it became known that Stollwerck was using such fictitious purchases and sales to ship over 40 wagons of cocoa from Italy to Germany, the English pressure“ tightened Measures "taken. Despite sometimes violent differences of opinion between Carl and Ludwig Stollwerck about this "purchasing policy", Ludwig Stollwerck, after increasing complaints from the cocoa trader Merkur AG, involved the authorized signatories Peter Harnisch (customs and haulage), Friedrich Eppler (office and accounting) and Heinrich Trimborn (banks and bulk purchases) into the shop and thus managed to secure a minimum supply of raw cocoa.

The war ended in 1918 for Stollwerck with immense losses, foreign holdings were expropriated, the company lost almost 70% of its assets, and the markets collapsed. In 1919 Ludwig Stollwerck ordered all departments to work out proposals for a reorganization that would take into account the changed framework conditions after the war. “Rationalization” became a catchphrase. In his strategy paper "A noteworthy consideration" from January 1919, he listed numerous weak points and pointed out where Stollwerck had competitive disadvantages. He described the Cologne factory as an “outdated factory” because of the outdated machines and systems and noted that the innovations had not been continued since the death of the ingenious machine designer Heinrich Stollwerck. In order to convince his brother Carl, who is responsible for manufacturing, he and other board members visited numerous competitor factories.

Then suddenly the banks created unexpectedly big problems. At the suggestion of the Reich authorities and house banks, Stollwerck had taken out extensive loans in neutral foreign countries to finance the supply of raw materials. The German banks had given guarantees for this. The share assets and the expected profits formed collateral. After the foreign shares, profits and collateral were lost through confiscation, repayments of foreign bank debts were made more difficult by the depreciation of the currency due to inflation. In this crisis situation, the house banks insisted on converting the guarantees into loans. Instead of helping the long-standing major customer Stollwerck by taking on risks by means of additional guarantees, the company was additionally burdened by high interest rates and demands for additional loan collateral . Under pressure from the banks, the share capital had to be increased. In 1921, the loans taken out for the purchase of goods were completely covered by seven million preference shares and 19 million ordinary shares. Ludwig Stollwerck suffered greatly from this solution, as the strength, security and stability of the family company were increasingly impaired by the rigorous banking policy.

With the death of Ludwig Stollwerck in 1922, the company lost the most agile strategist in the company's management. Neither the youngest brother Carl nor the next generation were able to close this gap. Ludwig Stollwerck's strategic approaches to rationalize and further increase productivity were not continued. Neither his brother Carl Stollwerck nor his descendants on the board were able to understand Ludwig Stollwerck's iron principles of running the family business and his visions, but pursued other, own goals. In 1929 the largest lender, Disconto-Gesellschaft , merged with Deutsche Bank AG . As a result of the takeover of A. Schaaffhausen'schen Bankverein, the Disconto-Gesellschaft had acquired larger shares. In addition, the family members had secured numerous loss-making speculations with their own blocks of shares. As a result, Deutsche Bank became a co-owner of Stollwerck AG and now increasingly interfered in the debtor's business.

The takeover of the former strongest competitor Reichardt in 1930 and many other speculative deals resulted in gigantic losses. The short-sighted financial behavior of the board members led straight to bankruptcy. The liquidation was averted under the direction of Deutsche Bank AG by its restructuringists Georg Solmssen and Karl Kimmich , but at the price that the Stollwerck family was deprived of entrepreneurial responsibility in 1931. In the correspondence between Karl Kimmich and Carl Stollwerck, he sharply criticized the management of Stollwerck and especially Franz and Fritz Stollwerck, the sons of Heinrich and Ludwig Stollwerck. From the letters and Kimmich's “restructuring measures” it becomes clear that under the rule of the bankers, Stollwerck products no longer consisted of chocolate, but only of numbers. Apparently based on Ludwig Stollwerck's maxim “the fate of the company is more determined by the sales department than by the company”, Kimmich wrote, “that in Cologne the sales force raped the company” and urged the cancellation of unprofitable products and a drastic reduction in distribution costs.

What is interesting here is the complete contradiction between Kimmich's condemnation of Stollwerck marketing and a study published in parallel in which the American economic expert Alfred D. Chandler junior compares the companies Cadbury and Stollwerck and expressly emphasizes that Stollwerck clearly does better marketing. Kimmich, for example, judged the Stollwerck collection pictures , a marketing instrument that went down in the history books because of its excellent sales promotion, as a "faulty disposition" and, against all protests, canceled their further production. Other, also incomprehensible decisions, such as the production ban for glass and advertising signs or the discontinuation of the company newspaper "Stollwerck-Post", prompted the Stollwerck employees to change his title from "Finance Director" to "Finance Dictator".

The next restructuring measure consisted of convincing Karl Stollwerck to leave the company "voluntarily". The correspondence of the renovators shows how they played off the board members against each other. For example, B. Kimmich expressly advises not to leave it in the presence of Karl Stollwerck that contrary to the announcement that the entire management board will be replaced, agreements had already been made with the management board lute about his stay in the company. Karl Stollwerck, who was 72 years old at the time, also had to lead violent arguments about his previously agreed retirement benefits and the agreed provision for his wife Fanny after his death, which the renovators drastically reduced before he left. In another letter, Solmssen instructed the legal adviser Schniewind to make it clear to Karl Stollwerck "that the path he has chosen [note: giving up the board post] is the only possible one in order to save him otherwise unavoidable very difficult hours". With Fritz Stollwerck, too, the renovators proceeded with similar rigidity. Solmssen threatened to resign Fritz Stollwerck "in a way that would be very unpleasant for him" if he tried to stay in office.

Most recently, at the end of 1931, the renovators forced all family members to leave the family business. Exceptions were Gustav Stollwerck, son of Peter-Josef Stollwerck, who ran the branch factory in Pressburg, and Adalbert Stollwerck, son of Franz-Karl Stollwerck, who had only been with the company since 1930. Gustav was forced to give up when he reached the age of 60 in 1933 and led a year-long legal dispute over his agreed pension payments. Adalbert stayed intermittently until 1960, when he died of a heart attack at the age of 56. With another move, the family members were deprived of their shares in the crisis year 1931, which they had deposited as security for loans. The renovators implemented a capital reduction , made the debit balances of the family members due and bought back the remaining shares well below their value after offsetting.

Under the Nazi regime, Kimmich turned Stollwerck into a model Nazi business and played a key role in the aryanizations operated by Deutsche Bank . He had close ties to Joseph Goebbels , whose sister was married to Kimmich's brother Max W. Kimmich . Kimmich continued to rationalize and boasted cost savings of over 1.2 million marks, of which 1.03 million marks from layoffs. Without consulting the managers in Cologne, Kimmich decided to close the branch in Romania. Board member Heinrich Trimborn, against whom Solmssen harbored great resentment because of his earlier loyalty to the family members, he presented the alternative of early forced retirement with greatly reduced pensions or voluntary termination.

Only from 1939 were profits made again. On May 31, 1942, 1,000 British bombers dropped their bomb load on Cologne, and over half of the Stollwerck factories were destroyed. The company was hit much worse by National Socialist politics, according to which raw cocoa was viewed and ostracized as a genetic toxin that would degrade the race because it came from cultures that Nazi ideologues classified as "inferior".

Stollwerck in the post-war years

After the Second World War , production was resumed in 1949. The family dynasty remained with Stollwerck AG until 1953 in the form of Richard Stollwerck, a member of the supervisory board. Another crisis loomed when the price control for chocolate was lifted in August 1964. After previous losses of millions at Stollwerck AG, the Cologne chocolate expert Hans Imhoff took over Stollwerck AG in January 1972. At that time it showed a loss of DM 10 million with a turnover of DM 100 million. Imhoff acquired 46.5% of the Stollwerck shares from Deutsche Bank AG. At a dramatic general meeting on December 21, 1972, he was presented as a renovator. In the following years he thoroughly restructured the company through a clear branding policy and a tight range (over 1,200 items were reduced to 190) to become one of the leading European chocolate groups.

In 1974 Imhoff sold the 57,356 m² Stollwerck company premises and the administrative building in Cologne's Severinsviertel, which was in need of renovation, to the Cologne financial broker and real estate agent Detlev Renatus Rüger (* 1933) for 25 million DM, although the value in an appraisal was only 5.5 million DM had been appreciated. In addition, the move to Cologne-Westhoven was funded by the City of Cologne 10 million marks. In return, in addition to the proceeds, he received 36% of the Stollwerck shares (equivalent to 23.5 million DM) from Rüger, a total of 48.5 million DM. Stollwerck AG was 82.5% owned by Hans Imhoff. After the city declared the site a redevelopment area on October 3, 1974, it acquired it from Rüger on July 4, 1978 for 40 million marks. After laying the foundation stone on April 18, 1975, Stollwerck moved to the new location in Cologne-Westhoven in December 1975. The depreciation company WITAG , which belongs to Rüger, financed the construction costs there with investor capital . From May 20, 1980, the abandoned old Stollwerck site was occupied to prevent the impending demolition. But from July 1987 the machine hall and anno room were demolished and the anno bar was rebuilt.

Every two years Imhoff Industrie Holding AG took over traditional and well-known chocolate manufacturers such as Eszet (1975), Waldbaur (1977) or Sprengel (1979). In January 1998, the Sarotti brand from Nestlé Deutschland AG was added, and Gubor followed in March 1999. After reunification , Imhoff became involved in East Germany. In January 1991 he took over the Thuringian chocolate and confectionery manufacturer "VEB Kombinat Süßwaren" in Saalfeld / Saale and invested there for 240 million DM.

Imhoff turned the general meetings of Stollwerck AG with the minority shareholders into amusing events with generous hospitality and natural dividends in the form of chocolate packages.

When the Stollwerck headquarters moved to Cologne-Westhoven in December 1975, Imhoff noticed the extensive pool of exhibits that were suitable for a museum. He decided to build the first chocolate museum , which he opened on October 31, 1993 under the name Imhoff Chocolate Museum in Cologne. It developed into a crowd puller for Cologne.

Sale of Stollwerck

Since Imhoff did not succeed in finding a family successor at Stollwerck AG, in April 2002 he sold his majority stake in Stollwerck AG, which has now grown to 96% (2001: 2,500 employees, € 750 million in sales and € 16.3 million Profit, market share 13.5%, for chocolate bars even 24.2%) for 175 million DM to the Swiss chocolate company Barry Callebaut AG. The remaining shareholders (4%) were settled in a squeeze-out . Production in Porz-Westhoven continued until March 2005, production there was relocated to the Stollwerck subsidiary Van Houten GmbH & Co. KG in Norderstedt . In October 2011, Callebaut sold the three German Stollwerck factories to the - much smaller - Belgian Baronie Group - the end of a long-established Cologne company with international renown.

literature

- Franz Stollwerck: Explanation . In: The Gazebo . Issue 33, 1867, pp. 528 ( full text [ Wikisource ] - protest note because of the secret media system of the present ).

- Bruno Kuske: 100 Years of Stollwerck History 1839–1939. Cologne 1939

Web links

- History of Stollwerck. (PDF; 32 kB) Cologne Chamber of Commerce

Individual evidence

- ^ Family register of the Stollwerck family

- ↑ Construction files 1865–1895, Dept. 208. RWWA.

- ↑ Bruno Kuske: 100 Years of Stollwerck History 1839–1939. Cologne 1939

- ↑ Peter Fuchs (Ed.), Chronicle of the History of the City of Cologne , Volume 2, 1991, p. 137

- ↑ Gabriele Oepen-Domschky: Cologne Business Citizens in the German Empire (= writings on the Rhenish-Westphalian Economic History, Volume 43). Cologne 2003

- ^ Gustav Wilhelm Pohle: Problems from the life of a large industrial company. Dissertation 1905

- ^ Foundation Rheinisch-Westfälisches Wirtschaftsarchiv

- ↑ Bruno Kuske: 100 Years of Stollwerck History 1839-1939. Cologne 1939.

- ↑ Historical-biographical sheets from industry, trade and commerce: Franz Stollwerck, Berlin 1898

- ^ Advertisement in the Kölnische Zeitung of January 29, 1912

- ^ Correspondence between Ludwig Stollwerck and Hans Rooschütz 1914, Stollwerck-Archiv, RWWA

- ↑ Stollwerck Archive, RWWA, 208-149-6

- ^ Kimmich to Stollwerck, Feb 1931, Federal Archives Potsdam R 8119F (Deutsche Bank)

- ^ Karl Kimmich and the Reconstruction of the Stollwerck Company, 1930-1932

- ^ Alfred DuPont Chandler: Scale and Scope - The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. First Harvard University Press, 1994

- ^ Kimmich to Karl Stollwerck: Letter dated February 24, 1931. Federal Archives Potsdam R 8119F (Deutsche Bank)

- ↑ Gerald D. Feldman: Thunder from Arosa: Karl Kimmich and the Reconstruction of the Stollwerck Company 1930-1932. University of California, Berkeley in Business and Economic History, 1997.

- ^ Kimmich to Solmssen: Letter of June 1, 1931. Federal Archives Potsdam R 8119F (Deutsche Bank)

- ^ Solmssen to Schniewind: Letter dated June 10, 1931. Federal Archives Potsdam R 8119F (Deutsche Bank)

- ↑ Solmmsen to Kimmich: Letter of June 2, 1931. Bundesarchiv Potsdam R 8119F (Deutsche Bank)

- ↑ Gerald D. Feldman: Thunder from Arosa: Karl Kimmich and the Reconstruction of the Stollwerck Company 1930-1932. University of California, Berkeley in Business and Economic History, 1997.

- ^ Ingo Köhler, Roman Rossfeld (ed.): Bankruptcies and bankrupts: history of economic failure . 2012, p. 332

- ↑ The 100 richest Germans: Hans Imhoff . Spiegel Online , February 16, 2001

- ↑ Peter Fuchs (ed.): Chronicle of the history of the city of Cologne . Volume 2. 1991, p. 313

- ↑ Money from sweet tooth . In: Die Zeit , No. 18/1975.

- ↑ The chocolate side . Wirtemberg

- ↑ From the confectionery to a global corporation . Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger, March 30, 2005

- ↑ Stollwerck the chocolate empire . Wallstreet online, April 10, 2002

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Stollwerck, Franz |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German chocolate manufacturer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 5, 1815 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cologne |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 10, 1876 |

| Place of death | Cologne |