Mountain range

A mountain group is a part of a mountain range that is delimited under geographical (in particular geological , orographic and orogenetic ), political / administrative , local, tourist or even arbitrary aspects , which usually comprises several mountain ranges and entire mountain ranges as well as the associated valleys . Larger mountain groups are sometimes further divided into subgroups. Mountain group divisions are primarily used in high mountains .

International standards with regard to the classification of mountains are currently not in sight. The system is often completely different depending on the area of application and national characteristics.

history

Even in ancient times , the writers of the ancient Greeks and Romans used names in their writings for individual sections of the southern side of the Alps, which reached at most to the highest ridges of the mountains and were named after their inhabitants, the country or the province. Although these were not mountain groups in the current sense, some names have been used up to our time. Examples are the Alpes Cottiae , Alpes Graiae , Alpes Pennine or Alpes Rhaeticae .

Around the middle of the 19th century, the first attempts were made to sift through and classify the seemingly immense number of Alpine peaks - Höhne mentions a number of 300,000 independent mountains - in order to give scientists, mountaineers and tourists an orientation aid. The area expert Adolf Schaubach was one of the first to make a serious attempt to divide the Alps. In his five-volume travel guide Die Deutsche Alpen , published between 1845 and 1847, the mountain range is divided into rivers, passes and geological aspects. By the German Alps , Schaubach understood the German-speaking Alps, an area that largely coincides with today's Eastern Alps . He divided these into Northern Alps , Central Alps and Southern Alps . The Schaubach Central Alps were divided into sections and further into groups, the northern and southern Alps were only divided into groups.

In his work The Geology of Switzerland, the Swiss geologist Bernhard Rudolf Studer was the first to try to classify the entire Alps according to geological criteria, but came to the conclusion that this was only possible to a limited extent. He later published a well-known work on the orography of the Swiss Alps .

In 1870, Carl von Sonklar created an alternative to Studer with his division into the Swiss and German Alps , which he expanded to include the entire Alps six years later. When in doubt, he weighted orographic criteria higher than geological ones. Its division separated the Western Alps (between the Mediterranean Sea and a line from the west bank of Lake Geneva via the Great Saint Bernard and the Aosta Valley ) from the Middle Alps (in the east to the Reschen Pass ) and the Eastern Alps . The Central and Eastern Alps were again divided into three parts from north to south. These large units were in turn divided into groups. Despite some shortcomings in his work, Sonklar's design is considered historically significant. Sonklar himself neglected to adapt his increasingly popular classification to the rapidly advancing knowledge of the Alpine region.

August Böhm von Böhmersheim , who dealt intensively with the geomorphology of the Alps, sharply criticized Sonklar in 1887:

“So far, the Alps have been broken down into individual sections according to the more important rivers, which have been referred to as 'natural' orographic groups. It was completely overlooked here that one was not moving on an orographic, but on a purely hydrographic basis. [..] Orography is primarily concerned with mountains, then with contour lines and valleys, and last but not least with rivers. "

In Sonklar's work, Böhm further criticized the delimitation of the Central from the Northern and Southern Alps. He himself orientated himself less on the rivers than on the course of the valleys, whereby he opposed the neglect of the landscape character and thus the geological context. After a long struggle, Böhm made a subdivision into western and eastern Alps , with the separation running at an angle to Lake Maggiore along the Rhine-Splügen line. With his division of the Eastern Alps , published in 1887, he created a contemporary work that could serve both scientific and tourist interests.

Since the founding of the first alpine clubs in the golden age of alpinism , interested mountaineers have increasingly turned to exploring and researching the Alps. A strictly scientific division of the Alps into mountain groups was less of a priority for mountaineers who were more interested in tourism than looking at the mountain world according to uniform " physiognomic " characteristics. Taking this into account, the Viennese Hugo Gerbers presented in 1901 a division of the Eastern Alps “intended for alpinists and mountain lovers” . Its multi-level structure, comprising 300 groups and subgroups, based on Böhm, was an extensive collection of all names and designations used at the time. The division between Eastern and Western Alps followed a new line, the trisection of the Eastern Alps into Northern, Primeval and Southern Alps was retained, and with the fine division of the Bavarian Prealps, German perspectives were introduced for the first time into the subject, which had previously been dominated by the Austrian side. Gerbers published his point of view in the leading alpine magazines in Germany and Austria.

Josef Moriggl's classification from 1924 was the next step in the classification of tourist mountain groups. Morrigl was General Secretary of the German and Austrian Alpine Club . So it is not surprising that its system, on which the association's register of refuges was based, was largely accepted in eastern alpine mountaineering circles until the 1970s.

The current Alpine Club division of the Eastern Alps (AVE 84) emerged in 1984 from a revision of the Moriggl system that began in the 1970s. The revision, for which Franz Grassler made a particular contribution, were changes in alpine language usage, alpine interest in previously neglected sub-groups and the upswing in skiing . With the AVE 84, the idiosyncratic delimitation of the Eastern and Western Alps of the Murrigl design was corrected. It now runs along the Rhine-Splügen line to Lake Como . The AVE 84 is today widely recognized as a tourist standard in Germany and Austria and is used by the DAV and OeAV .

The division into Eastern and Western Alps of the AVE 84 is not divided unreservedly in other Alpine countries. Compared to the Eastern Alps, the more complex structure and the more complicated topography of the French, Italian and Swiss Alps may have contributed to the fact that in France and Italy with the Partizione delle Alpi a tripartite division into Western, Central and Eastern Alps is maintained (the dividing line between the western and central Alps runs further west than in Sonklar's division of the Alps).

The Swiss Alpine Club pursues yet another approach with its division of the Swiss Alps , which often follows administrative requirements (cantonal boundaries). In the following, some mountains and mountain ranges are described in various SAC guides.

general overview

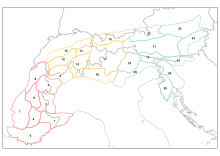

Even if it was not possible to agree on a uniform concept between the countries in the entire Alpine region, it is still possible - based on the AVE - to make an overall representation of a total of 106 mountain groups, as they are also presented by several authors and institutions. This allows a clear assignment of each mountain in the Alps, which does not mean that there are also different assignments, which is also pointed out at the relevant points.

See also

- SOIUSA - Suddivisione Orografica Internazionale Unificata del Sistema Alpino (= international unified orographic division of the Alps)

- Partizione delle Alpi

- Alpine club division of the Eastern Alps

- Classification of the Swiss Alps according to SAC

- Mountain group structure for the Austrian cave directory according to Trimmel

- List of mountain groups in the Eastern Alps (according to AVE)

- List of mountain groups in the Western Alps

literature

- The mountain groups of the Alps: views, systematics and methods for dividing the Alps . In: Peter Grimm and Claus Roderich Mattmüller (eds.): Scientific Alpine Club Hefts . tape 39 . German and Austrian Alpine Club, Munich 2004, ISBN 978-3-937530-06-2 .

- Hubert Trimmel : Mountain group structure for the Austrian cave directory . Ed .: Association of Austrian Speleologists. Vienna 1962.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ernst Höhne: 1000 peaks of the Alps . 2nd Edition. Weltbild, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-89350-388-9 , p. 8 .

- ↑ Ernst Höhne: 1000 peaks of the Alps . 2nd Edition. Weltbild, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-89350-388-9 , p. 9 .

- ^ The mountain groups of the Alps: views, systematics and methods for dividing the Alps . In: Peter Grimm and Claus Roderich Mattmüller (eds.): Scientific Alpine Club Hefts . tape 39 . German and Austrian Alpine Association, Munich 2004, ISBN 978-3-937530-06-2 , pp. 14th f .

- ↑ Ernst Höhne: 1000 peaks of the Alps . 2nd Edition. Weltbild, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-89350-388-9 , p. 4 .

-

^ Adolf Schaubach: The German Alps: a handbook for travelers through Tyrol, Austria, Steyermark, Illyria, Upper Bavaria and the adjoining areas; portrayed for locals and foreigners , five volumes, Jena 1845–1847

- First part: General description , 1845

- Second part: North Tyrol, Vorarlberg, Oberbaiern , 1845

- Third part: The Salzburg, Upper Styria, the Austrian Mountains and the Salzkammergut , 1846

- Fourth part: The area of the Etsch and adjacent river areas , 1846

- Fifth part: the south-eastern slope from the Grossglockner to Trieste , 1847

- ^ The mountain groups of the Alps: views, systematics and methods for dividing the Alps . In: Peter Grimm and Claus Roderich Mattmüller (eds.): Scientific Alpine Club Hefts . tape 39 . German and Austrian Alpine Association, Munich 2004, ISBN 978-3-937530-06-2 , pp. 16 .

- ^ The mountain groups of the Alps: views, systematics and methods for dividing the Alps . In: Peter Grimm and Claus Roderich Mattmüller (eds.): Scientific Alpine Club Hefts . tape 39 . German and Austrian Alpine Association, Munich 2004, ISBN 978-3-937530-06-2 , pp. 16 ff .

- ^ Bernhard Rudolf Studer : Orographie der Schweizer Alpen , yearbook of the SAC 1868/69, pp. 473–493.

- ^ The mountain groups of the Alps: views, systematics and methods for dividing the Alps . In: Peter Grimm and Claus Roderich Mattmüller (eds.): Scientific Alpine Club Hefts . tape 39 . German and Austrian Alpine Association, Munich 2004, ISBN 978-3-937530-06-2 , pp. 24 f .

- ^ The mountain groups of the Alps: views, systematics and methods for dividing the Alps . In: Peter Grimm and Claus Roderich Mattmüller (eds.): Scientific Alpine Club Hefts . tape 39 . German and Austrian Alpine Association, Munich 2004, ISBN 978-3-937530-06-2 , pp. 25 .

- ^ The mountain groups of the Alps: views, systematics and methods for dividing the Alps . In: Peter Grimm and Claus Roderich Mattmüller (eds.): Scientific Alpine Club Hefts . tape 39 . German and Austrian Alpine Association, Munich 2004, ISBN 978-3-937530-06-2 , pp. 25th ff .

- ^ The mountain groups of the Alps: views, systematics and methods for dividing the Alps . In: Peter Grimm and Claus Roderich Mattmüller (eds.): Scientific Alpine Club Hefts . tape 39 . German and Austrian Alpine Association, Munich 2004, ISBN 978-3-937530-06-2 , pp. 29 f .

- ↑ A comprehensive overview of the development towards AVE 84 Cf. Alpenvereinsjahrbuch BERG ´84 , pages 215–224