Georg Dibbern

Georg Johann Dibbern , also George John Dibbern (born March 26, 1889 in Kiel , † June 12, 1962 in Auckland ) was a German author , free thinker and self-declared “ citizen of the world ”.

Life

Georg Johann Dibbern was born in Kiel in 1889 as the son of Captain Adolph Friedrich Dibbern (1845–1895) and his wife Emma Juliane Tantau (1850–1907). He had two sisters. At the age of 50, his father died at sea as a result of malaria . Because of an asthma illness Dibbern his mother took him to Sicily for two years (1899-1901). After his return he lived first in Marne , then in Elmshorn with his sister and her husband.

The fact that his mother had cancer and was dying was kept a secret from Dibbern until he graduated from school in 1907. He withdrew from military service and instead went to sea, as a mate on the Flying P-Liner Pamelia to Chile and later on the Antuco . In 1909 he went ashore in Sydney and worked there as a construction worker on the Lithgow Tunnel (Glowworm Tunnel) and as a waiter at the Hydro Majestic Hotel in Medlow Bath in the Blue Mountains . At the Hydro Majestic Hotel Dibbern met the German Wilhelm Hugo Hildebrandt , with whom he traveled to New Zealand in 1910 .

In 1911 Dibbern returned to Sydney to start his own business there as a canoe dealer. When there were no major business successes, he traveled to New Zealand to see his friend Hildebrandt, who had since settled there as a water doctor in Napier . Since Dibbern had a driver's license, he began to work in the region around Dannevirke as a driver for the Māori . He later thanked the Māori for having brought him closer to the "warm soul of Polynesia". In view of the political developments in Central Europe, he was interned on Somes Island in June 1918 as an enemy of the war . A year later in May 1919 he was brought back to Germany on board the Willochra with around 900 other prisoners of war, including Captain Carl Kircheiß and Felix Graf von Luckner .

In the same year he met Elisabeth Vollbrandt, who was eleven years his junior. They married in January 1921. In anticipation of funds frozen in New Zealand, they bought a piece of land in Stocksee . Her son Jens Rangi was born in 1921, but died just six months after the birth. Three daughters followed: Frauke Wahine (1922), Elke Maata (1924) and Sunke Tai (1925).

In the years of ongoing German inflation , the young family lived in great economic hardship, especially since the funds expected from New Zealand were not released. Soon the property in Stocksee had to be sold. To make a living for his family, Dibbern began writing about his experiences in Australia and New Zealand. With the support of his friend Baron Albrecht von Fritsch , short anecdotes and stories appeared in various papers, including a. in the Vossische Zeitung . His wife Elisabeth made paper cuttings at home, the sale of which also contributed to the household budget. Until the Nazis classified them as Degenerate Art , their works were also exhibited nationwide. a. in the Folkwang Museum in Essen. For a short time, Dibbern also had sailing and boat supplies in Berlin . Dibbern invested part of its income from the sale of the property in the Tetsche Moeller shipyard in Kiel. When this venture also failed, he only owned one sailing yacht, a 10 meter double-ended, which he named Te Rapunga . The inspiration for the name, which means “longing” or “dark sun” in the Māori language, he took from the book Kulturreich des Meeres (1924) by Kurt von Boeckmann .

When Dibbern repeatedly came into conflict with his employers and colleagues because of his political views, he was forced to leave his family and Germany and return to New Zealand. He took his nephew Günter Schramm, his friend Baron Albrecht von Fritsch and his sister Dorothée Leber von Fritsch with him. They set sail from Kiel with the Te Rapunga in August 1930. Albrecht was the first to leave the crew and moved to England in 1936, where he later became known as a painter and author under the pseudonym George René Halkett . His best known work The Dear Monster (1939) took up his personal impressions of the pre-war period.

On the way with the Te Rapunga , Dibbern made the acquaintance of well-known sailors such as Conor O'Brien ( Saoirse ) and the Swiss painter Charles Hofer and his wife, the painter and author Cilette Ofaire ( San Luca ). A close friendship (letters) developed between Ofaire and Dibbern, which accompanied him until his death in 1962. To fill up the board cash, Dibbern soon took paying guests on board. In 1932, the Te Rapunga crew felt ready to cross the Atlantic. In Panama they met the pilot Elly Beinhorn , in Balboa Dorothée Leber von Fritsch left the yacht. Dibbern and Günter Schramm then challenged each other with a 100-day strike without touching the land. They passed Los Angeles shortly after the opening of the 1932 Summer Olympics en route to San Francisco , where they entered on September 20, 1932.

In March 1934, the Te Rapunga Auckland started in New Zealand. On land, Dibbern found that his 'Māori Spiritual Mother' Rangi Rangi Paewai, whose support he had hoped for, had since died. He set sail again and took part in the second Trans Tasman Race , where he sailed against Johnny Wrays Ngataki . The Te Rapunga won the regatta from Auckland to Melbourne (around 1,630 nautical miles ) with a time of 18 days, 23 hours and 58 minutes. She also won the next race to Hobart and then returned to Auckland.

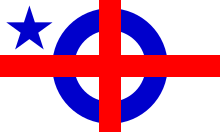

The hospitality that Dibbern experienced upon his arrival in Melbourne inspired him to declare the Te Rapunga a ship of friendship and a bridge for tolerance and brotherhood. With a new crew consisting of Roy Murdock, Maurice Black and the twenty-one year old Eileen Morris, he sailed to the Cook Islands , Hawaii and further north. When the Te Rapunga entered Canada , instead of the German swastika flag, it carried a flag created by Dibbern himself as a symbol of protest against political developments in Germany. At the same time, the Berlin apartment of his wife Elisabeth was searched by the Gestapo to find evidence of Dibbern's supposedly anti-German sentiments.

During his stay in Vancouver , Dibbern dictated his travel experiences to the typist Gladys Nightingale, who later became known as Sharie Farrell as a recognized boat builder in British Columbia . On the way through Desolation Sound he met the Canadian writer M. Wylie Blanchet on the Caprice . When Dibbern was banned from immigrating to Canada in 1939 , he became known in the press as "man without a country". With Eileen Morris he sailed the Te Rapunga back to San Francisco, where he was invited by Dan Seymour on the radio show "We the People" because of his story . In New York he submitted the manuscript of his travel experiences to the publisher WW Norton . Back at sea, he sailed to Hawaii . There he met several well-known sailors and dropouts of his time: Viator , who came from Tahiti , the famous Frenchman Éric de Bisschop on his catamaran Kaimiola on the passage to France, the Ketch Hula Gal on the way to Seattle and Captain Harry Pidgeon with his yacht Islander . In 1940, eight years before the American actor and activist Garry Davis gave up his civil rights and founded the global citizenship movement , Dibbern was already traveling with a self-made passport that identified him as a "Friend of all Peoples" and "Citizen of the World".

When Dibbern was also refused entry to the USA, he decided in 1941 to return to New Zealand with Eileen Morris. Even there, as a German, he was refused entry. As a potential spy, he was interned on Somes Island as an enemy of the war, as in 1918 . He was not released until 1946 and sailed with Eileen into the South Seas. A year later their daughter, Michaela Lalani Morris, was born. Under the tropical sun, they wrote articles about their travels and worked together on a new book, Ship without port , which went unpublished. When Dibbern returned to Hobart in 1950, he caused another stir with his self-made passport. "WORLD PASSPORT", reported numerous newspapers, "German-born John George Dibbern (60) produced a homemade passport when he arrived at Hobart, Tasmania, in his ketch Te Rapunga , from New Zealand - and it was accepted!"

I, George John Dibbern, through long years in different countries and sincere friendship with many people in many lands feel my place to be outside of nationality, a citizen of the world and a friend of all peoples. I recognize the divine origin of all nations and therefore their value in being as they are, respect their laws, and feel my existance solely as a bridge of good fellowship between them. This is why on my own ship I fly my own flag, why I have my own passport and so place myself without other protection under the goodwill of the world. - Dibberns Pass

Back on the mainland, he won £ 10,000 in a lottery. He invested part of the money in the purchase of Satellite (Woody) Island and Partridge Island with the aim of setting up a meeting place there. He found support from influential friends such as u. a. Reg Ansett, founder of Ansett Airlines, and Tasmanian Egyptologist and science fiction writer Herbert Leslie Greener. When he took part in the Trans Tasman Race in 1954, Dibbern caused a sensation with an all-female crew. They were the last to cross the finish line, but still made history. At the same time Eileen left Woody Island to go back to Napier with their daughter Lani and to enable her to attend school there. Dibbern was left alone and soon found that country life did not suit him. He put the islands up for sale so that they could set sail again. "I will sell because I want to sail as that is my life" he wrote to the American author Henry Miller . He began taking young people on board again and teaching them the sailing craft and life experience. For the first time, the Te Rapunga now also has an engine. With an untrained crew, Dibbern got into a hurricane in 1959 , in which the Te Rapunga lost her mast and finally came back to Auckland only with outside help.

Sensing the age, Dibbern decided to sail the Te Rapunga back to Germany to see his wife and children again, with whom he had been in contact for 30 years during his voyages without ever coming back to Germany. On the way to the post office with a letter to his wife Elisabeth in hand, George Dibbern died of a heart attack in Auckland on June 12, 1962.

Relationship with Henry Miller

After Henry Miller read Dibbern's book Quest and learned of its story, he contacted him by letter. The first contact developed into a pen friendship that lasted until Dibbern's death. Miller also campaigned for the payment of Dibbern's book royalties and organized fundraising campaigns to support Dibbern financially. To help sell the book Quest , Miller wrote a positive review that first appeared in Circle Magazine in 1946. The essay has since been part of the text collection Stand Still Like the Hummingbird (1962). A German translation of the essay has been added to Quest's German translation .

The long journey is not an escape, it is a search. The man seeks a way in which he could be of use to the world. Only at the end of the journey does it become clear to him what his task in life is, "to be a bridge of good will." That is Georg Dibbern and more. [...] Dibbern is neither a renegade nor a refugee, because the real refugee is a man who adapts to a world to which he does not say yes. No, it is the purity and authenticity of men like Dibbern that makes it difficult for them to integrate into our world. He desperately seeks to participate, to become one with his fellow human beings, but under the best of conditions, and that society does not seem to want to allow. Nor does he want to wait for the mythical day in the gray future to lead his ideal existence. He wants the ideal life now, right now. And that's the difference between a rebel and a man of spirit. There is a difference in favor of dibbing.

Even in difficult times, Miller tried to support Dibbern and his family. He sent aid packages to Elisabeth and the children in Germany and encouraged friends and acquaintances to do the same. So he gave Elisabeth a. a. a new typewriter after almost all of their property had been destroyed in the turmoil of war. Miller also tried to convince his publisher to bring out a German and French translation of Quest . After the war, Miller visited the Dibberns in Berlin.

When Miller heard of the dangerous stranding of the Te Rapunga in 1957, he printed an appeal for funds to raise funds for the restoration of the yacht.

The writer Henry Miller and the pen pal and sailor George Dibbern never met.

Afterlife

A biography authorized by the descendants of Dibbern appeared in 2004 under the title Dark Sun: "Te Rapunga" and the Quest of George Dibbern. A new edition of his book Quest , first published in New York in 1941, was published in 2008.

Dibbern's yacht Te Rapunga passed through different hands over the years until it, almost completely destroyed, was bought in 2017 by the “Bruny Island Costal Retreats and Nature Pact” in Tasmania. The restoration is on schedule by Denman Marine until the Australian Wooden Boat Festival 2021.

In Germany, the history of Dibbern has been largely forgotten. It was only after the research and publication of the Dibbern biographer Erika Grundmann that the German media took up the story again. The mare magazine published a profile under the title “Törn nach Utopia” and most recently Classic !, member of the Freundeskreis Klassiker Yachten . On February 3, 2013, the SWR broadcast a one-hour radio feature about Dibbern.

The art anthropologist Martina Kleiner recently paid tribute to Dibbern's role model for the present:

Perhaps the sailor George Dibbern [...] may be just a side note in history. At the same time she points out that in individual sailing on small boats there is also a large, supra-individual, socially idealistic dimension. Perhaps this memory can stimulate one or the other [...] to think about taking up Dibbern's utopia and "being a bridge of goodwill" especially through sailing. In any case, George Dibbern implemented the concept of a lived cosmopolitanism in all consistency as early as 1937.

Fonts

items

- “A wild ride. Memories from New Zealand ”, Hamburger Anzeiger , April 12th. 1927, pp. 1-2

- "The hasty passenger", Windausche Zeitung , Feb. 16, 1929, p. 2

- Various articles for the New Zealand sailing magazine SeaSpray .

Books

-

Quest . WW Norton, New York, NY, 1941

- Reprinted, RockRead Press, Manson's Landing, BC, 2008.

- Georg Dibbern . Under its own flag . In a sailboat across the world's seas . Translated by Arno Dohm. Classen Verlag, Hamburg, 1965.

- Ship without port . Unpublished manuscript.

Movies

Films about the restoration of Te Rapunga are intermittently posted on YouTube and Instagram by Bruny Island and Denman Marine. Bruny Island has also put the short film "Who is George Dibbern" online.

literature

- Borden, Charles A. Sea Quest. Macrae Smith Company, Philadelphia, 1967.

- Coffey, Maria. Sailing back in time . Whitecap Books, Vancouver, 1996.

- Davis, Garry. The World Is My Country . GP Putnam's Sons. New York, 1961.

- Dinklage, Ludwig. Ocean races: 70 years of transatlantic regattas . Dünen Verlag, 1936.

- Grundmann, Erika. “George Dibbern Sailor-Philosopher” Pacific Yachting , July 1999, pp. 32-34.

- Grundmann, Erika. "German George", New Zealand Memories , August / September 2000, pp. 41–45.

- Grundmann, Erika. "German George Returns", New Zealand Memories , April / May 2001, pp. 41-46.

- Grundmann, Erika. Dark Sun: Te Rapunga and the Quest of George Dibbern . David Ling Publishing, Auckland, NZ, 2004.

- Grundmann, Erika. "Galley Bay: A Dream Denied." BoatJournal , November / December 2005, pp. 44-48.

- Grundmann, Erika. "After the Book: More Tales and Treasures." New Zealand Memories , October / November 2006, pp. 64-65.

- Grundmann, Erika. "My Quest for Quest: How a Book Changed my Life." Senior Living , November 2009.

- Anonymous. "Man Adrift", BC Bookworld. Winter 2008-2009, pp. 11-13.

- Halkett, René. (Pseudonym for Albrecht von Fritsch). The Dear Monster, Jonathan Cape, London, 1939.

- Heriot, Geoffrey. In the South: Tales of Sail and Yearning . Forty Degrees South Publishing, Hobart, Tasmania, 2012.

- Holm, Don [ald]. The Circumnavigators: small boat voyagers of modern times . Prentice-Hall, 1974.

- Kleinert, Marina. Circumnavigator. Ethnography of a mobile lifestyle between adventure, leaving and emigration. transcript Verlag, 2015.

- David Loscalzo. The Adventures of the Circumnavigators in their small Sailing Boats. Books on Demand, 2016.

- McGill, David. The Guardians at the Gate: The History of the New Zealand Customs. Department. Silver Owl Press, Wellington, NZ, 1991.

- McGill, David. Island of Secrets: Matiu / Somes Island in Wellington Harbor . Roger Steel, Steel Roberts Ltd.,. Wellington, NZ, 2001.

- Mergen, Bernhard. Recreational Vehicles and Travel: A Resource Guide . Greenwood Press, 1985.

- Miller, Henry. Stand Still Like the Hummingbird . New Directions, New York, NY, 1962.

- Ofaire, cilette. Ismé: Longing for Freedom with biographical afterword by Charles Linsmayer. Pendo Pocket, Zurich, (1940) 1988.

- Reynolds, Reg. "A Vagabond in Gibraltar." The Gibraltar magazine , September 2011, vol. 16, no. 11, pp. 40-41.

- Ruby, Dan. Salt on the wind . Horsdal & Schubart, Victoria, BC, 1996.

- Selg, Anette. "Trip to Utopia". mare magazine . No. 91 (2012), pp. 84-90.

- Selg, Anette; Horns, Wilfried. "Utopia. Ever heard of Te Rapunga? From Georg Dibbern and his Te Rapunga? ”. CLASSIC! The magazine from the Friends of Classic Yachts . 4/2019, pp. 44-49.

- Vibart, Eric. “George Dibbern. Déserteur Céleste ”. Voiles et voiliers . June 2019, pp. 100-105.

- Wray, John. South Sea Vagabonds . HarperCollins Publishers (New Zealand), 1939.

Web links

- George Dibbern website by biographer Erika Grundmann

- Restoration of the Te Rapunga on Instagram

- Restoration of the Te Rapunga on YouTube

- “Törn nach Utopia” , article by Anette Selg, mare Magazin, No. 91, 2012

- "Art on the Island" , Erika Grundmann and the Story of George Dibbern, radio feature with Maureen Bader, Cortes Radio, Oct. 14, 2019.

- Sunshine Coast Museum & Archives , Farrell Family Collection

- Freundeskreis Classic Yachts

Individual evidence

- ↑ Erika Grundmann: German George . In: New Zealand Memories . Aug./Sept. 2000, p. 42-45 .

- ↑ a b George Dibbern: Quest . Ed .: WW Norton. New York 1941.

- ↑ Sam Jefferson: The Sea Devil. The Adventures of Count Felix von Luckner, the last Raider under Sail . Osprey Publishing, 2017.

- ↑ René Halkett: The Dear Monster . Jonathan Cape, London 1939.

- ↑ Eric Vibart: George Dibbern. Déserteur Céleste . In: Voiles et voiliers . June, 2019, p. 100-105 .

- ↑ Dorette Berthoud: Ciette Ofaire . In: Édition de la Baconnière . 1969.

- ^ Murray Davis: Australian Ocean Racing . Angus and Robertson, 1967, p. 40 (Murray seems to be confusing the races of 1934 and 1954, stating that Dibbern started with an "all female" crew as early as 1934.).

- ↑ Erika Grundmann: Galley bay: A Dream Denied . In: Boat Journal . 10 Nov - 8 Dec 2005, pp. 44-48 .

- ↑ Man Adrift . In: BC Bookworld . Winter, September 2008, p. 11-13 .

- ↑ Don [ald] Holm: The circumnavigators. Small boat voyagers of modern times . Prentice Hall, 1974, p. 163-164 .

- ^ World Passport . In: Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail . May 11, 1950.

- ↑ Henry Miller: Private communication . 1958.

- ↑ Georg Dibbern: Under its own flag . Claassen Verlag, 1956 (foreword by Henry Miller).

- ^ Anette Selg: Trip to Utopia . In: mare magazine . No. 91 , 2012, p. 84-90 .

- ↑ Anette Selg; Wilfried Horns: Utopia. Ever heard of Te Rapunga? From Georg Dibbern and his Te Rapunga? " In: Freundeskreis Classic Yachten (Ed.): Classic! No. 4 , 2019, p. 44-49 .

- ↑ Martina Kleinert: circumnavigators. Ethnography of a mobile lifestyle between adventure, leaving and emigration . transcript, 2015, p. 340 .

- ↑ Bruny Island: Who is George Dibbern? In: YouTube. February 7, 2019, accessed February 20, 2020 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dibbern, Georg |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Dibbern, Georg Johann; Dibbern, George John |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German author, free spirit and citizen of the world |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 26, 1889 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kiel |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 12, 1962 |

| Place of death | Auckland |