Big gap

The Great Fugue, Op. 133 in B flat major , was composed between 1825 and 1826 for a string quartet by Ludwig van Beethoven . The work dedicated to Archduke Rudolph was originally the finale of Beethoven's String Quartet No. 13 in B flat major, Op. 130 .

In 1826 Beethoven published a piano arrangement for four hands for the Great Fugue under opus number 134.

Emergence

The Great Fugue was originally intended to be the final movement of the String Quartet in B flat major, Op. 130 . Due to the novelty of the tonal language, which overwhelmed the performing musicians, Beethoven was asked by his publisher Mathias Artaria to write a conventional finale for op. 130. Beethoven complied with this request and published the original final movement with the independent opus number 133. According to the musicologist Gerd Indorf, the assumption that Beethoven took this step against his will is not justified according to the current state of research.

To the music

The work is based on the eponymous fugue . However, the work is not a pure fugue in the sense of Johann Sebastian Bach , rather the fugue of this piece is supplemented by additional elements. In fact, the number of joints in the work is limited to 40%; the rest of the fugue consists of freer Fugato style and homophonic elements. In this sense, Beethoven's friend Karl Holz , second violinist of the Schuppanzigh Quartet, which is close to Beethoven, recalled : “'To make a fugue,' said Beethoven, is not an art, I did dozens of them during my student days. But the imagination also wants to assert its right, and nowadays another, really poetic element must come into the traditional form ” .

When the Great Fugue was published, Beethoven described the nature of his sonata fugue as “tantôt libre tantôt recherchée” (“free and bound”). This refers to the execution of the joint, in which free and bound components alternate.

The overtura. Allegro - Fugue begins with a threatening sounding phrase, which is followed by a gentle passage. But a little later the rugged fugue and its variations set in. A variation of the four-tone group appears as an essential element of the fugue, which was already the basis of Beethoven's String Quartet No. 14 in C sharp minor, Op. 131 and String Quartet No. 15 in A minor, Op. 132 .

The overtura is replaced by a gentle meno mosso e moderato .

This is followed by a lively Allegro molto e con brio with its energetic variations, the theme of the fugue flows into it.

This is followed by another Meno-mosso-e-moderato section, in which the theme of the first Meno mosso e moderato is repeated, this time in a more rapid habitus.

The following section, again an Allegro molto e con brio , brings a light-hearted Allegro theme that has now also come to rest.

In the closing Allegro , the themes of the fugue , the first meno mosso e moderato , the overtura are repeated; the work comes to a lively end.

effect

First reactions to the Great Fugue

After a performance of the string quartet op. 130 on March 21, 1826 by the string quartet ensemble of Ignaz Schuppanzigh (before the exchange of the final movement), the “ Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung ” described the first movements of op. 130 with attributes such as “mystical” , and "Full of joy" and "mischievousness" , however, wrote about the fugue:

"But Ref. Doesn't dare to interpret the meaning of the fugitive finale: for him it was incomprehensible, like Chinese. When the instruments in the regions of the South and North Poles have to struggle with immense difficulties, when each of them works differently and when they cross each other through a myriad of dissonances by transitum irregularem, when the players, suspicious of themselves, are probably not quite pure either seize it, of course, then the Babylonian confusion is over; Then there is a concert, which at most the Moroccans can delight in, who, in their presence here in the Italian opera, liked nothing but the accordion of the instruments in empty fifths, and the common prelude from all keys at the same time. Perhaps some things would not have been written down if the master could also hear his own creations. But let's not rush to agree: Perhaps the time will come when what appeared to us at first glance cloudy and confused will be recognized clearly and in pleasant forms. "

The musicians, too, had problems with the musical style of the fugue, especially Karl Holz, which Ignaz Schuppanzigh was amused about : "Wood is falling asleep now, the last piece knocked him out" .

Even Beethoven's secretary and later biographer Anton Schindler hated the fugue and described this work by Beethoven as “the highest aberration of the speculative understanding” , and music critic Eduard Hanslick also called it “a strange document of his mighty but already strangely sick imagination” .

About the concerns of the publisher Artaria on the saleability of the op. 130 with the joint and his idea of the separation of which reported Karl Holz 1857:

“The art dealer Math. Artaria, to whom I had sold the property rights to the B flat major quartet on behalf of Beethoven (the fee was 80 ducats), now gave me the extremely difficult task of getting Beethoven there instead of the elusive fugue another, more accessible, last piece to write for the executing as well as the capacity of the audience. I now introduced Beethoven to the fact that this fugue, a work of art outside the realm of the usual, even his latest unusual quartet music, was a work of art, that it had to stand on its own, but also deserved its own opus number. Artaria would be happy to pay special tribute to a new finale. Beethoven wanted time to think it over, but on the following day I received a letter in which he agreed to comply with the wishes; for the new finale I should ask for 12 ducats "

The musicologist Klaus Kropfinger sees an "interplay" in the joint approach of Artaria and Holz ; as a result of this, the separation of the joint was “already preprogrammed” ; Kropfinger especially interprets Holz's behavior as “continuous 'psychological warfare'” . In contrast, there is a message from Karl Holz to Beethoven: “Yesterday the quartet was rehearsed at Artaria; [...] we played it twice; Artaria was quite delighted, and when he heard it for the third time he found the fugue quite understandable ” .

Beethoven's string quartet op. 130 was accepted for a long time with the newly composed finale, and in the first 50 years after its creation it was performed in 214 performances, according to statistics by the cardiologist and amateur quartetist Ivan Mahaim ; the Great Fugue, on the other hand, was played only 14 times during this period.

Discussion about the separation of the Great Fugue

Since then, there has been heated debate over the years as to whether Beethoven's decision to publish the original finale separately and replace it with a new final composition is to be regarded as final. Anton Schindler considered the new finale, which in his opinion resembled many of the other quartet movements written in earlier periods, "in terms of style and clarity" , as much more accessible.

The opposite side of this dispute, to which u. a. Arnold Schönberg and his colleagues in the Kolisch Quartet are of the opinion that Beethoven's decision was not an artistic one, but a marketing one; he would have been urged to do so by publishers and friends. With this in mind, Beethoven expert Erwin Ratz wrote :

“The fact that Beethoven let himself compose a new finale was an act of resignation [...]. Despite all the genius, which cannot be denied in the new finale, we have to say with the utmost determination that this movement has no inner relationship to the rest of the quartet. In every sensitive musician, the onset of the light rondo finale after the unearthly cavatine has faded will always trigger an unbearable shock "

Klaus Kropfinger sees the reason for Beethoven's approach in Beethoven's financial difficulties: "In this context, Beethoven's late consent to the separation of the fugue finale can also be seen" . Gerd Indorf, however, considers it unlikely that Beethoven would have subordinated his artistic convictions to an additional fee of just twelve ducats.

Indorf is just as skeptical about the thesis of seeing the separation as an “act of resignation” (Ratz), in the sense that Beethoven would have responded to the negative reaction from the audience: As Hermann Scherchen put it, “the final fugue was so displeasing, that Beethoven was moved to compose a new final movement after rejecting a first draft ” . But since Beethoven had been able to deal with the audience's lack of understanding of his works several times in the course of his life, it was, according to Indorf, unlikely that he would have given in to the public's taste. According to the Dutch musicologist Jan Caeyers, Beethoven's approach was purely musically justified: As a result, Beethoven came to the realization that the imbalance between the first five movements of the string quartet op.130, which were harmonious and accordingly put the audience in a relaxed mood, and the powerful, energetic fugue is too extreme; consequently he would have considered it necessary to compose a new, more peaceful finale.

Beethoven had already proceeded similarly in the past. The final movement of the “ Kreutzer Sonata ” originally comes from the Violin Sonata op. 30,1 , which is now ended by a variation movement. An anecdote tells us that Beethoven allegedly even considered replacing the choral finale of the “ Ninth Symphony ” with an instrumental movement.

A first performance of the String Quartet No. 13 in B flat major op. 130 with the fugue as the finale did not take place until 1887; this performance, too, was to remain the exception for a long time. Even in the editions of 1910 and 1921 of Theodor Halm's quartet monograph, written in 1885, the fugue is described as “perhaps the most ingenious eye music that has ever been written” ; "But when listening wants a pure, artistic satisfying impression Set only partially." .

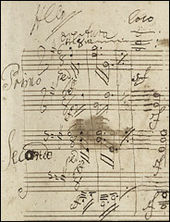

In the 20th century, the Grosse Fugue was finally given more attention and rated as more valuable than the newly composed finale. Today the autograph of the Great Fugue is in the Biblioteka Jagiellońska in Kraków .

Piano version

While the Great Fugue was still part of the Quartet op. 130, the publisher Artaria made Beethoven the offer that he should produce a piano version of the fugue “for better understanding” . When Beethoven refused, at Holz's suggestion, the pianist Anton Halm was entrusted with the transcription ; this task was completed at the end of April. Beethoven, however, did not like Halm's piano version, but was only able to start creating his own piano version in the second half of August 1826, after completing the String Quartet No. 14 (C sharp minor) op. 131 . He wrote to Karl Holz:

"... I ask you to tell Mr Mathias A. that I definitely do not want to force him to take my piano reduction, so I am sending you the Halmische KA so that you (if Artaria should refuse it) you as soon as you mean K. have received the extract, hand it over to Halm (schen) M (athias) A (rtaria) right away - but if Mr A. wants to keep my piano reduction for the fee consisting of 12 ducats in gold, all I ask is that it be in writing from is given to him. "

It was only in this phase in the first half of September that the idea of publishing the fugue as an independent work and composing a new finale for op. 130 arose. Karl Holz reported: "Artaria is delighted that they accept his proposal, he gains a lot from the fact that both works are sought individually" . From September to November 1826 Beethoven was busy composing the new finale for op. 130 and was finally able to send it to Mathias Artaria on November 22, 1826. He published the Great Fugue in Vienna together with its piano version and the string quartet op. 130 on May 10, 1827, a short time after Beethoven's death.

For a long time the last information about the whereabouts of the original score of the piano version was that it was auctioned off in Berlin and went to an industrialist in Cincinnati ( Ohio ). His daughter handed over the score along with other manuscripts - including a sonata and a fantasy by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (both in C minor) - to a church in Philadelphia ( Pennsylvania ) in 1952 . Again, it is unknown what happened to the score until it was found in July 2005 by a librarian while cleaning up at the Palmer Theological Seminary in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania. At an auction by Sotheby’s on December 1, 2005, an initially anonymous buyer acquired the manuscript for the equivalent of 1.95 million US dollars. The buyer was the publicly shy multibillionaire Bruce Kovner, who later revealed his identity and gave the score to the Juilliard School in February 2006 , which added the score to their online manuscript collection.

literature

supporting documents

- Matthias Moosdorf : Ludwig van Beethoven. The string quartets Bärenreiter; 1st edition June 26, 2007, ISBN 978-3-7618-2108-4 .

- Gerd Indorf: Beethoven's string quartets: Cultural-historical aspects and work interpretation Rombach; 2nd edition May 31, 2007, ISBN 978-3793094913 .

- Harenberg Culture Guide Chamber Music, Bibliographisches Institut & FA Brockhaus AG, Mannheim, 2008, ISBN 978-3-411-07093-0

- Jürgen Heidrich: The string quartets , in: Beethoven-Handbuch , Bärenreiter-Verlag Karl Vötterle GmbH & Co. KG, Kassel, 2009, ISBN 978-3476021533 , pp. 173-218

- Lewis Lockwood : Beethoven: His Music - His Life. Metzler, 2009, ISBN 978-3476022318 , pp. 344-383

further reading

- Theodor Helm: Beethoven's string quartets. Attempt of a technical analysis of these works in connection with their intellectual content , Leipzig 1885, ³1921.

- Ludwig van Beethoven: works. New edition of all works , section VI, volume 5, string quartets III (op. 127–135), ed. from the Beethoven Archive Bonn (J. Schmidt-Görg et al.), Munich Duisburg 1961ff.

- Ivan Mahaim: Naissance et Renaissance des Derniers Quartuors , 2 volumes, Paris 1964

- Joseph Kerman: The Beethoven Quartets , New York 1967

- Ekkehard Kreft: Beethoven's late quartets. Substance and substance processing , Bonn 1969

- Arno Forchert : Rhythmic problems in Beethoven's late string quartets , in: Report on the international musicological congress in Bonn , 1970, Kassel et al., 1971, pp. 394–396

- Rudolf Stephan : On Beethoven's last quartets , in: Die Musikforschung , 23rd year 1970, pp. 245–256

- Hermann Scherchen : Beethoven's Great Fugue, Op. 133 , in: For musical analysis , ed. by G. Schumacher (= ways of research , volume 257) Darmstadt 1974, pp. 161-185

- Emil Platen : A notation problem in Beethoven's late string quartets , in: Beethoven-Jahrbuch 1971/72 , ed. by Paul Mies and Joseph Schmidt-Görg, Bonn 1975, pp. 147–156

- Klaus Kropfinger: The divided work. Beethoven's string quartet Op. 130/133 , in: Contributions to Beethoven's Chamber Music , ed. by Sieghard Brandenburg and Helmut Loos, Munich 1987, pp. 296-335

- Emil Platen: About Bach, Kuhlau and the thematic-motivic unity of Beethoven's last quartets , in: Contributions to Beethoven's chamber music. Symposion Bonn 1984. Publications of the Beethoven-Haus Bonn. New series, 4th series, volume 10, ed. by Sieghard Brandenburg and Helmut Loos. Munich 1987, pp. 152-164

- Ulrich Siegele: Beethoven. Formal strategies of the late quartets. Music Concepts , ed. by Heinz-Klaus Metzger and Rainer Riehn, issue 67/68, Munich 1990

- Klaus Kropfinger: Beethoven - Under the sign of Janus. Op. 130 ± op. 133. The unwillingly made decision , in: About music in the picture , ed. by R. Bischoff et al., Volume 1, Cologne-Rheinkassel 1995, pp. 277-323

- Klaus Kropfinger: Fugue in B flat major for string quartet "Great Fugue" op. 133 , in: Beethoven. Interpretations of his works , ed. by A. Riethmüller et al., 2 volumes, Laaber, ²1996, volume 2, pp. 338-342

- Martin Geck : On the philosophy of Beethoven's Great Fugue , in: Festschrift for Walter Wiora for his 90th birthday , ed. by Christoph-Hellmut Mahling and Ruth Seiberts, Tutzing 1997, pp. 123-131

Web links

- Great Fugue, Op. 133 : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Internet presence of the online manuscript collection "JuillardManuscript Collection"

- Video: The Alban Berg Quartet plays the great fugue in 1989 [1]

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gerd Indorf: Beethoven's string quartets: Cultural-historical aspects and work interpretation Rombach; 2nd edition May 31, 2007, p. 425ff.

- ↑ Lewis Lockwood : Beethoven: His Music - His Life. Bärenreiter and Metzler, Kassel and Stuttgart / Weimar 2009.

- ^ Gerd Indorf: Beethoven's string quartets: Cultural-historical aspects and work interpretation. 2nd Edition. Rombach, Freiburg / Berlin / Vienna 2007, p. 431.

- ^ Wilhelm von Lenz : Beethoven. An art study , 5 volumes (Vol. 1–2 Kassel 1855, Vol. 3–5 Hamburg 1860), Volume 5, p. 219.

- ↑ Ludwig van Beethoven: Konversationshefte , ed. by Karl-Heinz Köhler, Grita Herre, Dagmar Beck, et al., 11 volumes, Leipzig 1968-2001, volume 8, p. 225ff.

- ↑ Ludwig van Beethoven: Konversationshefte , ed. by Karl-Heinz Köhler, Grita Herre, Dagmar Beck, et al., 11 volumes, Leipzig 1968–2001, volume 8, p. 246.

- ^ A b Anton Felix Schindler : Biography of Ludwig van Beethoven , 2 volumes, Münster, 1871, reprint Hildesheim etc. 1994, volume 2, p. 115

- ^ Eduard Hanslick : From the concert hall. , Vienna / Leipzig 1897, p. 184

- ↑ a b c Klaus Kropfinger: The split work. Beethoven's string quartet Op. 130/133 , In: Contributions to Beethoven's chamber music . Symposion Berlin 1984. Publications of the Beethoven-Haus Bonn, new series, 4th series, volume 10, ed. by Sieghard Brandenburg and Helmut Loos. Munich 1987, (pp. 295-335), p. 335, note 109

- ↑ Ludwig van Beethoven: Konversationshefte , ed. by Karl-Heinz Köhler, Grita Herre, Dagmar Beck, et al., 11 volumes, Leipzig 1968–2001, volume 10, p. 104

- ↑ Ivan Mahaim: Naissance et Renaissance des Derniers Quartuors , Vol. I., Paris 1964, p. 206

- ^ Klaus Kropfinger: Beethoven - In the sign of Janus. Op. 133 ± op. 133. The reluctantly made decision. , In: About Music in Pictures , ed. by B. Bischoff et al., Volume 1, Cologne-Rheinkassel 1995, (pp. 277-323), p. 310

- ↑ Gerd Indorf: Beethoven's string quartets: Cultural-historical aspects and work interpretation Rombach; 2nd edition May 31, 2007, p. 428

- ↑ Hermann Scherchen : Beethoven's Great Fugue Opus 133 , In: For musical analysis , ed. by G. Schumacher, ways to research , volume 257, Darmstadt 1974, (p. 161-185), p. 164

- ↑ Gerd Indorf: Beethoven's string quartets: Cultural-historical aspects and work interpretation Rombach; 2nd edition May 31, 2007, p. 429f.

- ^ Jan Caeyers: Beethoven - The lonely revolutionary , CH Beck-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-65625-5 , p. 734f.

- ↑ Lewis Lockwood: Beethoven: His Music - His Life. Metzler, 2009, p. 361

- ↑ Alexander Wheelock Thayer : Thayer's Life of Beethoven , revised and ed. by Elliot Forbes, Princeton, NJ 1964, p. 895

- ↑ a b Theodor Helm: Beethoven's string quartets. Attempt of a technical analysis of these works in connection with their intellectual content , Leipzig 1885, 1921, p. 171

- ↑ Jürgen Heidrich: The String Quartets , in: Beethoven-Handbuch , Bärenreiter-Verlag Karl Vötterle GmbH & Co. KG, Kassel, 2009, ISBN 978-3476021533 , p. 206

- ↑ Ludwig van Beethoven: Correspondence , Complete Edition, ed. by Sieghard Brandenburg, 7 volumes, Munich 1996-1998, Volume 6, No. 2194, pp. 274f.

- ↑ Ludwig van Beethoven, Konversationshefte , ed. by Karl-Heinz Köhler, Grita Herre, Dagmar Beck et al., 11 volumes, Leipzig 1968–2001, volume 10, p. 197

- ↑ “The New York Times” of October 13, 2005 - “A Historic Discovery, in Beethoven's Own Hand” (in English)

- ↑ "CBC News" of October 13, 2005 ( Memento of March 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) "Handwritten Beethoven score resurfaces" (in English)