Occidental schism

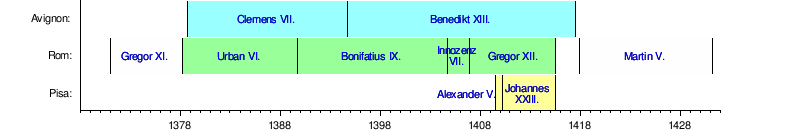

The Western Schism , also known as the Great Schism or Great Western Schism , was a temporary religious split within the Latin Church with competing papal claims in Rome and Avignon from 1378 to 1417. The split should not be confused with the Oriental Schism , which was used to permanently separate the Orthodox and Catholic Churches. In contrast to other faults, for example the schism in the time of Frederick I , this schism did not arise through the influence of a secular ruler, but within the church itself. It was mainly a problem between France and Italy, but affected the entire West out.

The main history of the later schism was the Avignon papacy from 1309 to 1376, during which the papal residence was relocated from Rome to Avignon, France. In 1376 Pope Gregory XI. the return to Rome. His successor Urban VI, elected under controversial circumstances in 1378 . expanded the French-dominated college of 16 cardinals by 29 new cardinals, which the previous ones rejected. They declared Urban incapable and in Avignon elected the French Clement VII as antipope , thus completing the schism.

Since for a long time neither an abdication nor an arbitral tribunal could be enforced, the Council of Pisa was convened in 1409 , which the meanwhile elected successor Benedict XIII. (Avignon) and Gregory XII. (Rome) was declared deposed and Alexander V installed as the new Pope. Due to a lack of acceptance by the existing popes, there were now three competing incumbents instead of just two. Only the Council of Constance (1414-1418) and the mediation of King Sigismund were able to finally overcome the split. With the deposition of the incumbent popes and the recognized election of Pope Martin V on November 11, 1417, the schism ended.

Emergence

There was already a strong contrast between the papacy and the rising kingship in France in the 13th century, which had reached a climax under the pontificate of Boniface VIII (1294–1303). In 1305, the French-dominated College of Cardinals elected the Archbishop of Bordeaux as Pope Clement V. This was not only - which was not unusual at the time - crowned outside Rome, but also resided permanently in France. From 1309 Avignon became the preferred papal residence. That meant after the peak in the 13th century a departure from the papal universalism, because while the Pope in Rome and the Papal States fairly autonomously was, he had to Avignon around little lands which were also completely surrounded by French territory. The papacy thus became dependent on the French crown, which turned out to be fatal , for example in relation to the Templar order . The popes lost their bipartisan authority.

The successors of Clement V continued to build Avignon into a papal residence, which indicated that the Roman bishop would remain permanently away from his episcopal city of Rome. Because of the loss of authority and the associated political problems, this policy was criticized even then by intellectuals such as Francesco Petrarca ("Exile of Avignon").

In 1376, the now ruling Pope Gregory XI decided. to give in to the pressure and return to Rome. Two women who were later canonized contributed significantly to this - Catherine of Siena (one of the four recognized church teachers ) and St. Birgitta of Sweden . When Gregory died in 1378, however, the Romans feared that the new Pope might also take his seat in Avignon, because nothing had changed in the French dominance in the college of 16 cardinals. The election of the Pope was correspondingly chaotic. The day before, armed men invaded the conclave area and demanded the election of a Roman as Pope. On April 8, 1378, the cardinals agreed not on a Roman, but at least on an Italian: the Archbishop of Bari named Bartolomeo Prignano . But because the conclave was again stormed by Roman citizens on election day, the Cardinal Seniors Tebaldeschi were pushed forward as the supposedly newly elected Pope for a short time - in order to save themselves. It was only a day later that Bartolomeo Prignano's election was announced, who would become Urban VI. called. The turmoil of the conclave later gave the cardinals the opportunity to publicly contest the election results.

Pontificate of Urban VI.

Urban VI. Soon proved to be very autocratic and rigorous, also towards his Senate, the cardinals and the curia. In particular, the eleven French cardinals and the Spaniard Peter von Luna , who later became the antipope, soon moved away from him. They complained that the election took place under duress and that the elected had also proven to be incapax and mentally ill. In August 1378 they therefore declared him deposed.

Urban VI. then appointed 29 new cardinals , which significantly enlarged the quorum. The three Italian cardinals remaining at the Curia protested against this - Tebaldeschi had since died - because the Pope and cardinals usually decided together on the appointment of new cardinals. However, the cardinals could not have any interest in expanding the circle, because the income of the college would then have had to be distributed among more heads.

Therefore, the protesting cardinals left the papal court and reunited with the French. On September 20, 1378, they elected Robert of Geneva Pope Clement VII in Fondi . This sealed the schism: two popes competed for the claim to be the true holder of the highest ecclesiastical power. However, the split between the Churches differed fundamentally from previous cases, because in these cases it was mostly kings and emperors who had established compliant counter-popes in a dispute with the Pope ; the occidental schism, on the other hand, arose in the midst of the church. At the same time, it was a revolutionary act that the College of Cardinals granted itself the authority to depose a Pope and elect a successor.

The historical assessment of the events turns out to be difficult. The cardinals could well be assumed to have national and selfish motives for the double election. On the other hand, from a canonical point of view, it was already clear then that the election of a mentally ill person to be Pope could not be valid. This assessment was not only made by the cardinals, but also by court officials and supporters of Urban VI. divided. In addition, the reason that the election was made under duress was also not made out of thin air. The validity of the Urban VI election. is therefore just as uncertain as the invalidity of the election of Clement VII.

Obediences

|

Immediately after the election of Clement VII, Western Christianity began to split into obediences (from Latin oboedientia "obedience"). France, Scotland and Spain declared Clement VII a rightful Pope. The German Empire was divided, but Emperor Charles IV and his successor Wenceslaus supported Urban VI, as did England, Hungary and other territories. The split was a tremendous tactical advantage for the princes: the Pope was an important factor in the European power structure in the Middle Ages, on whose blessing the legitimation of the rulers often depended. The system of obedience made the respective pope vulnerable to blackmail: the prince could always threaten to simply change obedience in the event of a contradiction. This benefit also threatened to cement the resulting system. For better or worse, the two popes and their respective successors had to get involved in a power game that threatened to undermine the moral authority of the papacy.

Strive for unity

Regardless of the political benefits, the schism was perceived as a scandal. Considerable efforts were therefore made from the beginning to win back church unity. There were various ways of doing this:

- First, the military solution ( via facti ): The settlement of power disputes with armed force was not unusual in the Middle Ages. In fact, there were numerous skirmishes, both large and small, between the obediences, but without really giving any party an advantage.

The University of Paris, the most recognized and famous educational institution in the West at the time, finally suggested three further options:

- a voluntary abdication ( via cessionis )

- submission to arbitration ( via compromissi ) and

- the decision by a general council ( via concilii ).

Call for a council

The convening of a general council seemed the most promising to contemporaries, so that the call for it grew louder and louder. In Savona in 1407 negotiations between the two obediences took place. The college of cardinals did not separate. In June 1407 13 of them met in Livorno . There they decided to convene a council in Pisa on March 25, 1409 . That, in turn, was revolutionary: a general council of the universal church had never been convened by a college of cardinals without consulting the pope or emperor. The initiative was by no means a given. The church of the Middle Ages was strongly influenced by the juridic organization. There was therefore a broad debate among theologians and canon lawyers about the question of who could have the decision-making authority in the present case.

Due to the influence of the Empire on the occupation of the Roman bishopric, the popes had strengthened their own position in the constitutional structure of the church through legal training, especially under Popes Gregory VII and Boniface VIII. In order to eliminate the influence of the emperor, the Pope of can no longer be judged by any worldly authority (prima sedes a nemine iudicatur) . However, a door had been left open: A Pope who had fallen into heresy or insanity would lose his office, and the decision would fall to the general council. The problem with this approach, however, was that - unlike in the Orient - the constitution of the council in the Western Church had changed in the second millennium. Councils were no longer convened by the emperor, but by the pope. A council without a pope therefore seemed unthinkable.

In order to avoid such uncertainties regarding the legitimation of a council, attempts were made for more than 30 years to end the schism in other ways. Only when this turned out to be fruitless did the cardinals convene the council. Not only was the fact that cardinals were called up in itself problematic, but also that one way or another some of the cardinals belonged to a false obedience and were therefore illegitimate.

However, the initiative met with broad approval: over 600 clergy took part in the council. The parallel convened councils of the two Popes Gregory XII. (Roman obedience, in Cividale ) and Benedict XIII. (Avignon Obedience, in Perpignan ) didn't have nearly as many participants. The overwhelming approval of the clergy for the council in Pisa isolated the two popes for a long time.

Council of Pisa

The council marked the visible rise of conciliarism , i.e. the theory that the general council stands above the Pope and is also allowed to judge him. Theologians like Marsilius of Padua , Michael of Cesena and Wilhelm von Ockham already had corresponding preliminary considerations during the so-called poverty dispute between the Franciscans and Pope John XXII. made.

The council declared to be a legitimate, general council of the whole church. It quoted the two Popes Gregory XII. and Benedict XIII. to Pisa and after their refusal made them a formal heretic trial as stubborn schismatics . In addition, it declared itself that the stubborn persistence in the schism could only be viewed as heresy because of the division of the church that this entailed. This created the decisive basis for further action. On June 5, 1409, the council finally deposed the two popes. The council elected Alexander V as his successor on June 24th .

But that did not end the schism: Because Benedict XIII. and Gregory XII. insisted on their claims, there were now three obediences instead of two. Thus the council was formally a failure. But the obedience of the deposed popes had shrunk sharply after Pisa, the most important powers (except Spain, which remained with Benedict XIII.) Confessed to Alexander V and his successor, John XXIII. The path of the council had proven to be promising and should be taken again.

Council of Constance

In 1414 a new attempt was made in Constance to finally overcome the schism. His convocation and his success in this matter are above all a merit of the German King Sigismund , who the unwilling Johannes XXIII. withheld consent to the council. Through preliminary negotiations, Sigismund also ensured that the council enjoyed broad legitimation by attracting as many participants as possible from all parts of the church.

John XXIII expected the council to be confirmed in office. Since the majority of the participants were now Italians and this largely with Gregory XII. had broken, his prospects were actually good. But at the council an unusual reform of the voting rights was undertaken after a short time: From then on the principle of one participant, one vote was no longer valid , but voting was done according to nations, with each nation only having one vote. The universities, whose professors (mainly from Paris) exerted a great influence on the council, were the model for this regulation. The Italians had only one vote against the three other nations of England, Germany and France, as well as that of the College of Cardinals.

Among the other nations was John XXIII. not well liked. The leading figures of the council were the Cardinals Peter von Ailly , Guillaume Fillastre , Francesco Zabarella and the Paris University Rector Jean Gerson . These convinced the council that the only solution could be to depose all three popes and elect a new pope recognized by all. When John XXIII. Recognizing this strategy and also having to fear that he could be tried for earlier missteps, he fled the city on March 20, 1415. As a result, the council got into a serious crisis, because without the Pope, who had also taken larger parts of his followers with him, there was a risk of loss of legitimacy .

Once again, Sigismund proved to be the savior of the situation, and it was announced in the city that the council was by no means dissolved, but would be continued. The council now declared that if the good of the church required it, it could restrict the full papal authority . The sovereignty of the council over the pope was established on April 6, 1415 with the decree Haec sancta . It subsequently formed the Magna Charta of conciliarism, but initially only referred to the church assembly of Constance (Haec sancta synodus ... = This holy synod ...). John XXIII was arrested by Sigismund's troops and brought back to Konstanz, where he was tried. On May 29, 1415 he was deposed.

Abdication of Gregory XII. and deposition of Benedict XIII.

According to John XXIII. the council had to deal with the other two popes. Gregory XII, already over 80 years old, soon gave in. He recognized the Council of Constance as a legitimate council of the Church and had the legate Giovanni Dominici declare his resignation. This ensured that his obedience would follow the Pope to be elected in Constance.

Benedict XIII, who in the meantime resided in Perpignan , declared himself ready in principle to abdicate, but attached conditions such as the relocation of the Council of Constance, which he did not approve. He then upheld his claim and fled to Peñíscola . However, Sigismund managed to have the Spanish kingdoms withdraw his support and come to Constance as the fifth council nation. Benedict XIII. finally isolated. He was tried for refusing to resign and was deposed on July 26, 1417. The fact that he continued to regard himself as a legitimate Pope until his death on June 10, 1423 was insignificant due to the lack of a noteworthy following. In 1429 the remaining supporters of Benedict and his successor Clemens VIII recognized the pontificate of Martin V.

End of the occidental schism

After the deposition or abdication of the three popes, the way was clear for a new election. The College of Cardinals assembled in Constance agreed to allow representatives of the nations to participate in the election. On November 8, 1417 the papal election began, in which 53 voters participated. They decided on November 11th for the Italian Oddo di Colonna, who gave himself the name Martin V after the day saint Martin of Tours . With that the church had a Pope again recognized by all.

literature

- Hubert Jedin (ed.): Handbook of Church History. Volume 3: The Medieval Church. Half Volume 2: From the High Middle Ages to the eve of the Reformation. 2nd unchanged edition. Herder, Freiburg i. B. 1973, ISBN 3-451-14001-2 .

- August Franzen: Small Church History. extended by Roland Fröhlich, reviewed by Bruno Steimer. 25th edition. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2008, ISBN 978-3-451-29999-5 .

- Hubert Jedin: Short Council History. 6th edition. Herder, Freiburg 1978, ISBN 3-451-18040-5 .

- Erich Meuthen : The 15th Century . 3. Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-486-49733-2 . ( Oldenbourg floor plan of the story vol. 9)

- Klaus Schelle: The Council of Constance 1414-1418. An imperial city in the focus of European politics . 2nd Edition. Stadler, Konstanz 2010, ISBN 978-3-7977-0557-0 .

Web links

- Ansgar Frenken: Collective review The Great Western Schism . In: H-Soz-u-Kult . September 1, 2010, accessed August 31, 2010.

Individual evidence

- ^ Robert N. Swanson: Universities, Academics and the Great Schism , 1979, p. 1.

- ^ August Franzen: Small Church History. 25th edition. P. 223.

- ^ August Franzen: Small Church History. 25th edition. P. 226f.

- ^ A b c d Hubert Jedin: Small Council History. 6th edition. 1978, p. 63.

- ^ August Franzen: Small Church History. 25th edition. P. 227.

- ↑ a b August Franzen: Little Church History. 25th edition. P. 229.

- ^ August Franzen: Small Church History. 25th edition. P. 230.

- ^ A b Hubert Jedin: Small Council History. 6th edition. 1978, p. 64.

- ↑ a b c August Franzen: Small Church History. 25th edition. P. 231.

- ^ A b c Hubert Jedin: Small Council History. 6th edition. 1978, p. 65.

- ^ August Franzen: Small Church History. 25th edition. P. 232.

- ^ August Franzen: Small Church History. 25th edition. P. 233.