Himba

The Himba , actually OvaHimba or Ovahimba ( Himba is singular), is an indigenous people or clan in northern Namibia and in southern Angola that can be culturally differentiated from the Herero . The Himba belong to the Bantu language family . This pastoral people is said to have comprised around 16,000 people in 2002, but belonging to the Himba is often a personal decision that is immediately recognizable from the outside. They are considered to be the last (semi) nomadic people of Namibia, while in Angola they are in the company of the Vakuval (e) and the Mundimba with this way of life .

history

Himba migrated as part of the ancestors of today's Herero in the 15th and 16th centuries. Century from the Bechuanaland (today's Botswana ) in today's Namibia, a small part later also in adjacent areas of today's Angola . In Namibia they lived as nomadic hunters and gatherers in the northwest, in Kaokoland on the Kunene (between Angola and the former homelands Owamboland and Damaraland ). The name "Himba" appears in the sources much later. The missionary Heinrich Vedder called them that for the first time . This did not emphasize an ethnic distinction, but a socio-cultural one, because the Himba shared language and culture with the Herero and Ovatjimba . The latter also lived as cattle herders, but they were less successful, the Himba herds were considerably larger. Tjimba became a term for poor, unsuccessful shepherds with little or no cattle. This led to the fact that many Tjimba referred to themselves as Himba and soon also considered themselves. In 1927 it was established that 63% of the population were considered Himba, but only 18% were Tjimba. However, when the Tjimba protested against their political marginalization in 1952, 47% of the Kaokoland were considered Tjimba and only 34% were Himba. This was not only a sign of a changed self-image, but also a change in belonging to the country and its indigenous population. This was directed against the supremacy of the Herero.

The settlement areas, spatially separated from the other Herero peoples, encouraged separate development, not least due to the influence of the missionaries on the Herero and their armed conflicts with the Nama . The Christianized Herero in Hereroland (in the vicinity of Okahandja , Windhoek and Otjimbingwe ) soon differed from their "pagan" clothes (the Herero costume for women, which was "invented" by the wife of the missionary Hahn and was borrowed from the Victorian era) from their "pagan" ones. Brothers and sisters in Kaokoland and soon viewed them as second-rate Herero, which accelerated and deepened the separation. Therefore, Himba people generally do not wear western clothes, prefer body painting and emphasize hair accessories. Conversely, simply changing these customs makes it possible to become a Herero.

In the 19th century, the Himba were exposed to raids from the south and also got caught up in the war between the German colonial rulers and the Herero (1904). Since they were also affected by rinderpest in 1897, many of them fled to Angola , which was under the Portuguese colonial power . In their economic hardship, the Portuguese groups tried growing millet and sorghum . There they also took part in commercial big game hunts, which decimated the huge populations between 1870 and 1895, and cattle theft. Many Himba left Angola in Portugal after 1900, accelerated after 1910 - perhaps to protect their traditional way of life. Chief Kahengombe caused several groups to move south again. Around 1910 a larger Himba group returned under their leader Muhona Katiti, followed by the Herero leader Vita Tom , whose group settled in Kaokoland in 1917, which he had visited in 1912. The German colonial authorities also encouraged return migration, possibly because there was a drastic shortage of workers after the Herero uprising. The Himba were considered a mild people who could easily be led with tact.

In 1923 South Africa , which would rule the country for over seventy years , assigned them a reservation . The Kaokoland was divided into three reserves. Vita Tom led the Herero, Kahewa-Nawa the Tjimba and Muhona Katiti the Himba. The 1927 census shows that Vita Tom had 829 followers, Kahewa Nawa 378 and Muhona Katiti 426. Another 1,549 people could not be assigned to any of the three chiefs. In addition, the 1200 or so Herero in southern Kaokoland were not included in this division. But they were not allowed to trade or let their cattle graze freely. So the once wealthy ranchers became impoverished. The so-called Homeland Kaokoveld (Kaokoland) did not even have its own government.

In the 1950s there were ten Councilor Headmen who belonged to the Kaokoland Tribal Council , but whose meetings they rarely attended. Instead, the Herero prevailed in Opuwo, especially since the local official assumed that the Himba headmen had no control over their people. In 1952 there was a complaint for the first time that the Himba had been expelled from their land many times.

When drought and war raged in the 1980s, the culture of the Himba was on the brink. Around two thirds of their livestock (around 130,000 animals) perished. Many men were forced to enlist in the South African army and fought against the guerrillas who fought for Namibia's independence. At the same time as the end of the uprising and Namibia's declaration of independence, the rain came back and the Himba herds increased again.

But now the project of a huge reservoir on the Kunene and the planned flooding of their land threatens the Himbabeans. The culture of the Himba can also be overwhelmed by tourism and traffic developments and add them to the fate of numerous other indigenous peoples : lethargy, alcohol and social disintegration.

Since Namibia's independence, ethnology has dealt with the Himba even more than before, which has led to the fact that one speaks of a "Himbanization" of Namibian ethnology. The Himba were seen as self-sufficient, isolated but successful shepherds, the Tjimba as poor hunters and gatherers and the Herero as those who had fallen into western civilization. Kaoko was stylized into a pre-colonial, untamed part of the country by the 1970s at the latest, far removed from the brutalities and inequalities of the rest of the colonial world.

Todays situation

The Himba are divided into three recognized traditional administrations :

Himba in Namibia (the people are estimated at around 7000 people) still live today - comparatively unaffected by European civilization - in their constantly adapting and changing tradition as nomadic cattle breeders , hunters and gatherers , especially in Kaokoland, but also in Angolan Side of the Kunene. Many live in materially extremely simple circumstances without an identity card or certificate. This Bantu tribe was never wealthy in the traditional sense, but the Himba feel that they are wealthy when they have a large herd of cattle and the harvest was good. Around 100 years ago, its members were attacked and robbed by warlike Nama. They had to ask for alms from the neighbors and were therefore called "Himba", which means beggar.

Human rights

Groups of the last remaining hunters and gatherers are said to be (as of 2012) kept in guarded camps in the northern part of the Kunene region in Namibia, despite complaints from the traditional Himba leaders that the Ovatwa are being held there without their consent and against their will.

In February 2012, the traditional Himba leaders signed two declarations submitted by Earth Peoples , an international human rights organization, to the African Union and the United Nations .

In the declaration of the most affected Ovahimba, Ovatwa (actually Ovatue ), Ovatjimba and Ovazemba against the Orokawe Dam in the Baynes Mountains , where a dam is now to be built 60 km below the previous location, the regional Himba chiefs and communities declared who live near the Kunene River and the Bannes Mountains, expressed their protests and objections to the planned dam. The declaration of the traditional Himba chiefs from Kaokoland in Namibia was signed by all Himba leaders and lists a whole series of human rights violations of their indigenous rights, which they believe are being perpetrated by the government against the Himba.

As a result, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya, visited the Himba in September 2012 and noted their problems and concerns.

On November 23, 2012, hundreds of Himba and Zemba protested in Okanguati, Epupa, against Namibia's plans to build a dam.

On March 25, 2013, over a thousand Himba protested in Opuwo to draw attention to the ongoing human rights violations. They expressed frustration that their traditional leaders are not recognized as such by the government. They also appealed against plans to build the Orokawe Dam in the Baynes Mountains on the Kunene , against culturally inadequate education, the lack of land rights in the area where they have lived for centuries, and against the implementation of the Communcal Land Reform Act, 2002 a.

Culture

Subsistence farming

The Himba predominantly raise fat-tailed sheep and goats, but they count their wealth in the number of their cattle. They also practice agriculture. Camphor tree and mopane play an important role . Wooden vessels, spoons and traditional wooden pillows are made from the brown camphor tree. The watery, sweet pulp of the tree is chewed, as is that of the black camphor tree. In addition to building material, the Mopane also supplies flexible branches that serve as ropes. To do this, they are peeled and placed in water.

Oral culture, dance and song

The Himba are a people with an oral tradition. They often come together to dance and sing together, with the theme of the songs, which are often spontaneous, informing the group of people's worries, plans or successes.

Domination and responsibility

The districts of the Himba are subject traditionally each one as King (king) or chief man called (chief) of each living in his district people should regard as belonging to his family. Its task is to keep hunger and thirst away from its people, to distribute the pastures and to maintain contact with government agencies. Within the community he is responsible for maintaining peace and balancing things out, ideally also for medical care and drug control, as well as for the preservation of culture. He is responsible for weddings and funerals, as well as for the care of the bereaved. In contrast to the Windhoek government, the Himba insist on choosing their own chief. The administrator in the capital decides on the recognition or dismissal of the headmen.

The connection to the people is established by the headmen who present complaints or suggestions to the King . The senior councilor has a similar task . These men advise the king, but can also depose him if he does not inform them sufficiently about relevant events. The ideal is the king, who only exceptionally intervenes in the decision-making process, except in deliberations.

Life cycles, external signs

A special feature is the lack of the lower four incisors, which are broken out at a young age. The teeth are knocked out with a special piece of wood without anesthesia, after which the leaves of the mopane tree are used for pain relief and disinfection. In the course of life, the outward appearance of both men and women changes with regard to body painting, jewelry and clothing.

Jewellery

Her clothing - both that of men and women - is limited at first glance to tight loincloths made of calfskin and fur and occasionally self-made sandals (made from car tires). However, hairstyle and jewelry, whose complexity only ethnologists could see for a long time, are much more important to them . You can z. For example, you can tell how many children a Himba woman has by looking at the costumes. Some of the women wear brass rings on their wrists and ankles. Collars that have a symbolic meaning are also often worn. Women with white collars are still without children, mothers wear brown ones. The women also carry mussels, which traders swap for meat or leather. They are passed on to the daughters.

Hairstyle

The hairstyles testify to the social status of a community member. Before puberty, girls wear their hair in long fringes, adorned with strings of pearls and falling into the face; with two pigtails facing towards the forehead, however, marriageable young women. Married women present themselves in over-shoulder-length, twisted lichen rubbed with ocher from their faces and adorned with fur hoods. Mourners wear their hair uncombed and loose. After the first menstruation, the girls, who are now considered women, are allowed to wear lamb skin on their heads.

The young men wear a central, backward braid, the sides are shaved off like a mohawk. Married men usually wear a black headscarf, which they only do without when they are very sad.

The families each have their own style.

Body painting

Particularly noticeable is the greasy cream with which men and women rub themselves. It not only gives them a red skin color, but also protects against the extremely hot and dry climate of the Kaokoland and against mosquitoes. It consists of butter fat and ocher color , called okra . The coloring component in the natural red ocher is iron oxide, plus the aromatic resin of the Omuzumba bush.

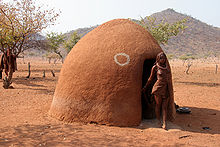

House building

The Himba houses are cone-shaped and made with palm leaves, clay and dung. As the Himba regularly roam between the farms with their cattle, some houses are only inhabited during certain periods. The building material is mainly obtained from the mopane tree.

Inheritance law

While the cattle are passed on to the sister's children, their own children receive the cattle from their maternal uncle. Only the “holy flock”, the consecrated fire sticks and the responsibility for the holy fire are passed on to the son. The fire must never go out because it maintains the connection between the living and the dead.

Subsistence farming and tourism

In addition to raising cattle (cattle, goats and fat-tailed sheep) and a little corn and pumpkin cultivation, some Himba men are engaged in the production of simple souvenirs and tools that they sell directly to visitors.

Overall, the Himba seem to have initiated a turnaround: management communities determine cattle and tourism. There are mobile schools where the children learn English. Its culture has withstood many threats (drought disasters and the Namibian liberation struggle ) and it will change in some places - but it has a chance of survival again. The situation of the Himba who remained in the vicinity of Opuwo , the only city in Kaokoland, is different.

gallery

literature

- Gerhard Unterkofler: Namibia. With a detour to Victoria Falls and the Okavango Delta; [an adventurous journey in the land of the San and Himba] (exhibition catalog); Gnas: Weishaupt, 2005; ISBN 3-7059-0225-3 .

- Eberhard Rothfuss, Erwin Vogl, Ernst Struck , Klaus Rother: Ethnotourism - Perceptions and Action Strategies of the Pastoral Nomadic Himba (Namibia): A hermeneutical, action-theoretical and methodical… contribution from a socio-geographical perspective ; University of Passau, Chair of Anthropogeography, 2004.

- Peter Pickford, Beverly Pickford, Margaret Jacobsohn: Himba - The Nomads of Namibia ; Edition Namibia, 3; Göttingen, Windhoek: Hess, 1998. ISBN 3-9804518-3-6 , 1998.

- Klaus G. Förg, Gerhard Burkl: Himba. Namibia's ocher people ; Rosenheim: Rosenheimer Verlagshaus, 2004. ISBN 3-475-53572-6 .

- Heidi and Eberhard von Koenen: The old Kaokoland . Klaus Hess Verlag, Göttingen, Windhoek 2004, ISBN 3-933117-24-0 .

- Henrica von der Behrens: Horticulture of the Himba: arable land use by a pastoral nomadic group in northwestern Namibia , Institute for Ethnology, Cologne 2003.

- Kuno FR Budack; Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt: The Himba ; in: Wulf Schiefenhövel, Johanna Uher, Robert Krell (eds.): In the mirror of others. From the life's work of the behavioral scientist Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt ; Realis, Munich 2003; ISBN 3-930048-03-5 ; Pp. 46-55.

- Carol Ezzell: The Himba and the great dam , in: Spectrum of Science, 2002, 74-83.

- Michael Bollig: Risk Management in a Hazardous Environment: A Comparative Study of Two Pastoral Societies ; Pokot NW Kenya and Himba NW Namibia, habilitation in ethnology at the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Cologne, 1999.

- Michael Bollig: Contested Places. Graves and Graveyards in Himba Culture . In: Anthropos. Internationale Zeitschrift für Völker- und Sprachenkunde , Vol. 92 (1997), pp. 35–50.

Broadcast reports

- Jan-Philippe Schlüter: HIMBA-NOMADS - Life like 500 years ago , Deutschlandfunk - “ Background ” from June 22nd, 2014

Web links

- Living Museum of the OvaHimba

- HIZETJITWA Indigenous Peoples Organization (HIPO) (English)

- The Ovahimba Years¦Les années Ovahimba (English / French)

- Earth Peoples (Earth Peoples) Himba Leader Declaration to the UN February 2012 (English)

- Earth Peoples (EarthPeoples) Video by Rebecca Sommer

Individual evidence

- ^ John T. Friedman: Imagining the Post-Apartheid State. An Ethnographic Account of Namibia. Berghahn, 2011, p. 184.

- ^ John T. Friedman: Imagining the Post-Apartheid State. An Ethnographic Account of Namibia. Berghahn, 2011, p. 192.

- ^ John T. Friedman: Imagining the Post-Apartheid State. An Ethnographic Account of Namibia. Berghahn, 2011, p. 269, note 62.

- ↑ Patricia Hayes, Jeremy Silvester, Marion Wallace, Wolfram Hartmann: Namibia under South African Rule. Mobility & Containment, 1915-46 , Oxford, Windhoek, Athens, Ohio 1998, p. 183.

- ↑ Patricia Hayes, Jeremy Silvester, Marion Wallace, Wolfram Hartmann: Namibia under South African Rule. Mobility & Containment, 1915-46 , Oxford, Windhoek, Athens, Ohio 1998, p. 185.

- ^ John T. Friedman: Imagining the Post-Apartheid State. An Ethnographic Account of Namibia. Berghahn, 2011, p. 44.

- ↑ Patricia Hayes, Jeremy Silvester, Marion Wallace, Wolfram Hartmann: Namibia under South African Rule. Mobility & Containment, 1915-46 , Oxford, Windhoek, Athens, Ohio 1998, p. 190.

- ^ John T. Friedman: Imagining the Post-Apartheid State. An Ethnographic Account of Namibia . Berghahn, 2011, p. 190.

- ^ John T. Friedman: Imagining The Post-apartheid State. An Ethnographic Account of Namibia , Berghahn, 2013, p. 20.

- ^ John T. Friedman: Imagining The Post-apartheid State. An Ethnographic Account of Namibia , Berghahn, 2013, p. 20.

- ^ Indigenous coalition opposed to new dam . OSISA. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved on February 28, 2012.

- ↑ Indigenous Himba Appeal to UN to Fight Namibian Dam . galdu.org. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- ↑ Himba chiefs declaration . Earth peoples. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- ^ Namibian Minority Groups Demand Their Rights . newsodrome.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- ^ Declaration of the most affected Ovahimba, Ovatwa, Ovatjimba and Ovazemba against the Orokawe Dam in the Baynes Mountains . earthpeoples.org. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- ^ Declaration by the traditional Himba leaders of Kaokoland in Namibia . Earth peoples. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- ↑ Statement of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, James Anaya, upon concluding his visit to Namibia from 20-28 September 2012 . OHCHR. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Namibia: Indigenous semi-nomadic Himba and Zemba march in protest against dam, mining and human rights violations . Earth peoples. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ German GIZ directly engaged with dispossessing indigenous peoples of their lands and territories in Namibia . Earth peoples. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ↑ Himba, Zemba reiterate 'no' to Baynes dam . Catherine Sasman for The Namibian. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ↑ HIMBA DANCE in Omuhonga, Kaokoland, Namibia (February 2012). In: YouTube . Sommer Films, February 12, 2012, accessed March 8, 2012 .

- ^ John T. Friedman: Imagining the Post-Apartheid State. An Ethnographic Account of Namibia. Berghahn, 2011, p. 189.

- ↑ Rebecca Sommer asks traditional headmen and councilors about their ideas about government , 2012.

- ↑ Grundlegend: Margaret Jacobsohn: Preliminary notes on the symbolic role of space and the material culture among semi-nomadic Himba and Herero herders in Western Kaokoland, Namibia. In: Cimberbasia. 10 (1988) pp. 78-99.