Inuit art (Canada)

The term Inuit art describes the artistic activities of the Canadian Inuit , which began around the middle of the 20th century and subsequently conquered a sector of its own on the international art market , the sector of " Contemporary Canadian Inuit Art ". Art objects created by the Inuit prior to this period, which are mainly classified as “function- related art ”, are, however, generally assigned to ethnology or ethnology, and they can therefore be found primarily in their collections.

Function-related art

Sculptural works

As long as the Inuit lived as nomads , they could only allow themselves artistic activities if they did not cause transport problems. Therefore they created practically no art objects just for the sake of art ("l'art pour l'art"); they also had no Inuktitut word for art. When they were active in this field, it was mostly about decorating objects of everyday life with aesthetic decorations. However, this type of design is more likely to be attributed to handicraft and less artistic design, even if the Inuit demonstrated not only traditional technical skills but also a good sense of taste.

For such function-related artistic works, the Inuit, who live isolated from the rest of the world, naturally only consider materials that are available in the Arctic , i.e. primarily serpentine ("snake stone", steatinite) and serpentinite (serpentine slate ), more rarely the very soft steatite (" Soapstone "or talc). Materials of animal origin such as caribou antlers and (depending on the occurrence of the animals) ivory from walrus teeth and narwhal tusks as well as whale and walrus bones were also used. Animal skins were decorated using scraping techniques.

Drawing work

From the time before the first encounters with whites in the 16th century, the "pre-contact time", until well into the 20th century, their cosmology led the Inuit to believe in a magical power of drawing , according to which a picture is carried by the The act of drawing alone could become a reality. Drawing in the snow or z. B. on frost-covered areas was taboo and therefore strictly prohibited to children.

Apparently, however, the request from whites to depict certain facts or conditions in drawings (e.g. to sketch maps) broke this taboo, especially since completely new materials - paper and pencils - were now available for the first time. Narrative stone carving and drawing, an art of remembering personal experiences of the artist that is still practiced today, the actual art of the “post-contact time” found its origin here, but without immediately becoming a tangible reality (creation of works of art ).

Handicrafts

In the Inuit camps well into the 20th century, it was a typical task of a woman to make clothing in the traditional way from animal hides and skins, and this tradition is still upheld in many summer camps today. In order to obtain color differentiations, the animal skins were subjected to different treatments. By scraping or cutting the fur hair it was possible to emphasize the desired effect. In seal skins, shadow and color effects were created by shaving the hair to different lengths. Cut-out leather parts were also sewn onto the actual garment or inserted into recesses. All kinds of fur bags were decorated in the same way.

With the whalers, researchers and missionaries, wool and cotton had reached the Arctic at least since the turn of the 20th century. Then when the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) set up their trading posts, Inuit women were able to barter all kinds of sewing goods. Before long, the handicrafts were richly decorated with colorful woolen threads and glass beads; the embroidery material from the south stimulated the imagination and set completely new impulses.

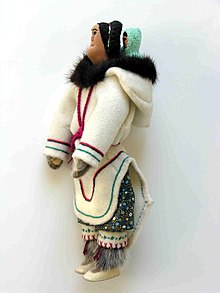

Traditional Inuit clothing was very popular with visitors to the Arctic, and they quickly found buyers. They were not only worn in accordance with their purpose here in the north: their owners also brought them to the south as souvenirs and thus ensured that Inuit handicrafts became generally known. Over the years in which the transport system constantly improved in the Arctic regions, the interest grew to the wide trade in such handicrafts, especially on Kamik (fur boots), gloves and amauti (Women's parkas). Carrier bags and wall hangings made of seal skin and artistic dolls made of various materials were also made by the women for sale and decorated with glass bead embroidery or traditional designs.

Environmental influences

The effects of environmental influences on the artistic behavior of the Inuit can be seen e.g. For example, the fact that in the course of the 19th century, with the deterioration of the climatic and thus also the survival conditions, the technical standards and all kinds of artistic expression of the Inuit declined. Carvings and decorations on everyday objects were now carried out much less frequently and with much less differentiation than before.

Contemporary art - beginnings in the 20th century

With such a history, it is not surprising that the sculpture art ( stone carving , English "carving") of the Inuit , known today as characteristic , did not begin until the late 1940s - at the time when the Inuit from traditional camps in permanent settlements moved. Increasing contacts with whites ("Qallunaat" in Inuktitut ) - also as clients - and targeted funding by the Canadian government, which was keen to open up other sources of income for the Inuit than just hunting, gave the impetus for the new art direction.

Anyone who deals with the then newly developed art forms is impressed by their originality, attention to detail and depth of expression. Inuit have an almost unlimited, experience-based trust in their creative abilities, and their sensitivity to technical structures and processes is astonishing to outsiders. One may rightly regret that the Inuit way of life has changed significantly over the past few decades under Euro-Canadian influence, leaving little time for cushioning adjustments. One may also complain that many of the people affected are currently neither at home in the new culture nor in that of their ancestors. However, the clash of traditional culture of the Inuit with that of a western industrial nation has brought about something extraordinary: a tremendous dynamism in the artistic field, a departure with undreamt-of power.

The growing interest in buying artistic works with a typical Inuit character sparked efforts by political circles, but especially those interested in marketing, to discover and promote artistic talent in as many Inuit settlements as possible. In the future, art should play an important role in economic value creation. In the course of time, as a result of the relatively remote location of the individual settlement areas, regional characteristics developed, which were shaped in particular by the availability of certain raw materials, but also by training and advice, taste and sales success of the artists. Following the needs, the conventional, function-related design is initially developing further, above all as a design for traditional utility and craft objects. In addition, however, real works of art that were not earmarked for a specific purpose were soon created.

Sculptures

This new artistic creation initially concentrated on sculpture. Mainly traditionally used materials found in the Arctic serve as raw materials: serpentine (" serpentine stone ") and serpentinite (serpentine slate) as well as marble (calcium carbonate), but also other types of rock such as dolomite (calcium-magnesium-carbonate) and quartz (silicon dioxide) - seldom the "soapstone" ( steatite ), which is too soft for artistic figures , although this mineral designation is most likely to have established itself in the trade and is still used today. Materials of animal origin such as caribou antlers and (depending on the occurrence of the animals) ivory from walrus teeth and narwhal tusks as well as animal bones are still widely used. The ceramic work carried out in Rankin Inlet , which requires clay minerals as raw material - an imported technique, is a specialty .

Initially, the sculptures were made by hand with an ax, chisel and hammer; In the meantime, electrical devices have become generally accepted (only some older women continue to work without electrical tools). It is polished with sandpaper of various grains.

The motifs for the sculptures are determined by tradition and everyday life of the Inuit, but also by the temptations of the art market. Polar bears are currently very popular, and so their representation outweighs numerically in new variants. But other motifs also originate from the arctic fauna, such as seals, caribou and birds. Many sculptures represent people - hunters, fishermen, mother and child, partly static-realistic, partly narrative (e.g. camp scenes). Sculptures based on the traditional animistic religion of the Inuit, such as the depiction of shamans or metamorphoses (humans into animals and vice versa), occupy a large space.

The sculptural work of the Inuit differs significantly from that of European artists in one respect: For Europeans, the motif is in the foreground; the material (stone, bronze, etc.) has to submit to it. Inuit, on the other hand, take a close look at the stone that they want to process into a sculpture in order to elicit the motif that is hidden in it; they are inspired by the material and its shape. If you z. For example, if you have found a rock that in your eyes surrounds a polar bear, a corresponding sculpture is created under your hands. Unlike European artists, Inuit artists do not keep any of their works in stock; Immediately after completion, the sculpture is brought to the cooperative or a local dealer so that it pays for itself in cash as quickly as possible. Art serves to earn money, not for self-realization.

Drawings and prints

At the beginning of the 1950s, the objects intended for general sale were still very traditional in terms of their type and production technology and predominantly handicrafts. That changed fundamentally in the second half of the decade: A project for the production of special "Inuit prints", which started in Cape Dorset in the early winter of 1957 and quickly became increasingly important, was now determined by completely new elements: This art is owed its emergence in the first place when the Inuit encountered the European-influenced culture of Canada, so, like pottery, is only possible through "imported technology".

Wall hangings, artistic dolls

In addition to the traditional raw materials of fur and leather, the contact with the Europeans brought the Inuit new materials for their work, especially fabrics for trimmings and glass beads as jewelry. With the move to settlements, artistic wall hangings were created for the first time - ornaments of this kind were not needed in the camp until then. Just like the artistic dolls that the Inuit women designed, the wall hangings are mainly made of duffel and felt with various applications made from the same materials or from traditional leather or fur. In the settlement of Pangnirtung (Panniqtuuq) a very special kind of artistic design developed: Inuit women use their own drawing templates that depict traditional cultural assets to weave wool tapestries imported from the south, which have long attracted great interest from collectors around the world.

Art as a factor for value creation

Contemporary Inuit art would hardly have been able to assert itself on the art market without the establishment of local cooperatives in such a way that it is now considered to be an important value-adding factor for Nunavut. These cooperatives, mostly under the management of whites from the south, successfully combined economic thinking with traditional values and activities.

The sale of serpentine sculptures, graphics and wall hangings has long overtaken the trade in hunting products (skins, antlers, ivory tusks); Annual sales in the arts and crafts trade sector have long since reached the double-digit million range (around 30 million euros in 2017). Presumably, in only a few regions on earth art and handicrafts have developed into such an important value creation factor as a proportion of the population as in the Nunavut territory, which has around 30,000 inhabitants.

Generations of Inuit artists

- Today the generation of artists who, towards the end of the 1940s, devoted themselves to the development of a new kind of Inuit art born out of tradition, with a lot of enthusiasm and great commitment, are usually referred to as the 1st generation of contemporary Inuit artists. There is no strict demarcation, but these were essentially Inuit who were born in the last years of the 19th century and in the first three decades of the 20th century; they were between 20 and 60 years old in 1950.

- As the 2nd generation, one sees, again only roughly, the cohorts born between 1935 and 1965.

- Those born later form the 3rd generation. With regard to future developments, it remains to be seen whether the creativity and artistic expressiveness of the initial phase will remain undiminished, will develop selectively or sink into opportunistic fashion trends.

Centers of contemporary Inuit art

Cape Dorset Arts Center (Kinngait)

The settlement of Cape Dorset ( Nunavut region Qikiqtaaluk ) played a prominent role in the eruptive development of artistic design in the Arctic, with a large number of artists representing the history of contemporary Inuit sculpture with mostly dramatic works, the heroic, elegant and playful Can take on traits, have significantly influenced. Hardly any other settlement let itself be captured by the new art as intensely as Cape Dorset and passed on such strong impulses to other communities. The situation in Cape Dorset on the southwest coast of Baffin Island was initially quite similar to that on the opposite side of the Hudson Strait , ie that in the arctic part of the province of Québec , today's Nunavik . Carving stone sculptures was a man's job; at most occasionally supports her in polishing the surface of children and women. The women, on the other hand, contributed to the increase in income by sewing and weaving baskets. However, it did not stay that way for long, and women also turned to the art of stone carving.

The foundation for the importance of the Cape Dorset settlement in the art sector was laid by James A. Houston , who recognized the unusually great potential for artistic talent and creativity among the Inuit and, together with his wife Alma, became government representative in 1951 (in collaboration with the Canadian Art Guild) settled here for a decade. With the aim of giving the Inuit, who since then only lived from hunting, new tasks that should grant them at least a certain degree of economic independence, Houston initially encouraged the creation of expressive sculptures, mainly serpentine, serpentinite and marble, which were used as raw materials Nearby quarries were extracted with primitive means in open-cast mining, as well as materials of animal origin such as parts of caribou antlers and occasionally walrus ivory.

At the end of the 1950s, the Inuit gained access to the technique of graphic work. The art of lithography, which was new to them, or, more correctly, the stone carving , which was similar to linocut , quickly met with great approval and allowed this branch of art to flourish in an unexpected way - initially in Cape Dorset, but knowledge of it quickly spread throughout the Northwest Territories (today Nunavut and remaining Northwest Territories) and in the Nunavik area (Province of Québec).

The initiator was James Houston, who, with tireless personal commitment , familiarized the residents of Cape Dorset with drawing on paper and with techniques from Europe and Japan . Such paper drawings, which subsequently served as the basis for stone cuts and etchings, were already used in the first prints. Primarily, however, the high-contrast and impressive decorations of hand-made caribou and sealskin bags and the traditional decorative drawings on ivory objects were ideal for conversion into graphics on paper.

In addition to the male artists who used to work as hunters and fishermen , many women now also engaged in activities that were new to them, in which they saw a way of contributing to the maintenance of the family. The whole treasure trove of orally transmitted stories and myths was often reflected in the themes dealt with; both narrative and decorative-artistic documents of Inuit culture were created .

In this way, Cape Dorset developed into an excellent art center for stone sculpture and printmaking. Sales were initially taken over by HBC, the only trading company in the area, before it was replaced in 1962 by a sales organization belonging to the Inuit themselves, the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative , which was managed by Terry Ryan as James Houston’s successor with great success until the turn of the millennium . It is thanks to her that the artists were able to assert themselves internationally in well-known galleries, and that today their works can be seen in major museums around the world.

Internationally recognized artists from Cape Dorset include:

- 1st generation: Parr (1893–1969), Peter Pitsiulak (1902–1973), Pitsiulak Ashuna [Ashoona] (1904–1983), Itidluie Itidluie (1910–1981), Abraham Itungat (1911–2000), Pauta Saila (1916 -2009), Padluq Pudlat (1916-1993), Usuituk Ipilie (1922-2005), Miaji Pudlat (1923-2001), Kenojuak Ashevak (1927-2013), Qaqaq Ashuna (1928-1996), Lukta Qiatsuq (1928-2004 ), Kiugak Ashuna (1933-2014);

- 2nd generation: Kananginak Putuguk [Pootoogook] (1935–2010), Aqjangajuk Shaa (* 1937), Napatsi Putuguk (1938–2002), Kellypalik Qimirpik (1948–2017), Umalluq Usutsiaq (1948–2014), Nuna Parr (* 1949), Uvilu Tunnillie (1949–2014), Uqituq Ashuna (* 1952), Arnaguq Ashevak (1956–2009), Qavavau Manumie (* 1958), Taqialuk Nuna (* 1958), Adamie Ashevak (* 1959), Pallaya Qiatsuq ( * 1965);

- 3rd generation: Cie Putuguk (* 1967), Annie Putuguk (* 1969), Tunu Sharky (* 1970), Tytusie Tunnillie (* 1974)

Baker Lake (Qamanittuaq)

In addition to Cape Dorset, the Baker Lake settlement in the Kivalliq region has an outstanding position in terms of the design of art objects. The promotion of artists and the development of special projects began a little later, namely in the mid-1960s, but then quickly became very popular. Typical of the sculptures made there is gray or black serpentine material, the structure and hardness of which determine the shape and motifs. These show more archaic forms and are characterized by dynamism and characteristic figurative structural elements; superfluous details can hardly be found. The musk ox motif is very common , of which the work of Barnabus Arnasungaaq is exemplary.

Graphic work began in 1970. At this time, Jack and Sheila Butler also began promoting textile art - primarily wall hangings - for which Baker Lake is now very famous.

Archaic forms are also preferred in the Kivalliq settlements of Rankin Inlet , Whale Cove and Arviat (formerly Eskimo Point), which are located directly on Hudson Bay . Unlike in Baker Lake, however, as various authors believe, the artistic representation tends more towards abstraction, which, however, does not apply unreservedly to textile work (wall hangings) and also not to pottery from Rankin Inlet.

Internationally recognized artists from the Kivalliq region include:

- Arviat: Luke Anautalik (1932–2006), Martina Pisuyui Anui [Anoee] (* 1933), Lucy Tassiur Tutswituk (1934–2012), Joy Kiluvigyuak Hallauk (1940–2000), Julia Pingushat (* 1948), George Arluk (* 1949)

- Baker Lake: Luke Anguhadluq (1895-1982), Jessie Unaq [Oonark] (1906-1985), Luke Iksiktaaryuk (1909-1977), Marion Tuu'luuq (1910-2002), Barnabus Arnasungaaq (1924-2017), Janet Kigusiuq (1926–2005), Victoria Mamnguqsualak (* 1930), Simon Tukumi [Tookoome] (1934–2010), Tuna Iquliq (* 1935), Irene Avaalaaqiaq (* 1941; especially wall hangings)

- Rankin Inlet: John Kavik (1897–1993), John Tiktak (1916–1981)

Pangnirtation

A third art center developed in the Pangnirtung settlement in the south-eastern part of Baffin Island (Nunavut region Qikiqtaaluk), where expressive wall hangings are preferably woven in the Uqqurmiut center for arts and handicrafts, but also significant graphic works are created alongside handicraft items.

Internationally recognized artists from Pangnirtung include:

- Elisapee Ishulutaq (* 1925), Annie Kilabuk (1932-2005), Andrew Qappik (* 1964)

Other Inuit settlements

- Other settlements in Nunavut where talented Inuit artists work are: Arctic Bay , Gjoa Haven , Hall Beach , Iglulik , Iqaluit , Kimmirut (formerly Lake Harbor), Kugaaruk (formerly Pelly Bay), Kugluktuk (formerly Coppermine) , Pond Inlet , Qikiqtarjuaq (formerly Broughton Island), Repulse Bay , Sanikiluaq (on the Belcher Islands ) and Taloyoak (formerly Spence Bay);

- in the Northwest Territories are the art settlements of Paulatuk and, above all, Ulukhaktok ;

- In Nunavik , the arctic part of Québec, three settlements are to be highlighted: Inukjuaq , Puvirnituq (formerly Povungnituk) and Salluit (formerly Sugluk).

Internationally recognized artists from these settlements include:

- Gjoa Haven : Judas Ullulaq (1937–1999)

- Iglulik : Luke Airut (1942-2018), Germaine Arnaktauyuk (* 1946, now based in Yellowknife)

- Taloyoak : Maudie Rachel Ukittuq, (* 1944)

- Ulukhaktok : Helen Kalvak (1901–1984), Elsie Anaginak Klengenberg (* 1946)

- Paulatuk : David Ruben Piqtukun (* 1950, now based in Toronto ), Abraham Anghik Ruben (* 1951, now based in Saltspring Island )

- Puvirnituq : Joe Talirunili (1899–1976), Davidialuk Alasua Amittu (1910–1976), Josie Pamiutu "Puppy" Papialuk (1918–1996)

See also

literature

- Maria Bouchard: An Inuit Perspective - Baker Lake Sculpture ; 2000, ISBN 0-9687071-0-6

- Lorraine E. Brandson: Carved from the Land ; Churchill MB 1994, ISBN 0-9693266-1-0

- Richard C. Crandall: Inuit Art - A History ; Jefferson, NC 2000, ISBN 0-7864-0711-5

- Maria von Finckenstein (Ed.): Celebrating Inuit Art 1948-1970 ; Hull (Gâtineau) 1999, ISBN 1-55263-104-4

- Maria von Finckenstein (Ed.): Nuvisavik - The place where we weave ; Hull (Gâtineau) 2002, ISBN 0-7735-2335-9

- Carol Finley: Art of the Far North - Inuit Sculpture, Drawing, and Printmaking ; Minneapolis 1998, ISBN 0-8225-2075-3

- Susan Gustavison: Arctic Expressions - Inuit Art and the Canadian Eskimo Arts Council ; Kleinburg ON 1994, ISBN 0-7778-2657-7

- Susan Gustavison (Ed.): Northern Rock - Contemporary Inuit Stone Sculpture ; Kleinburg ON 1999, ISBN 0-7778-8564-6

- Ingo Hessel: Inuit Art ; New York 1998, ISBN 0-8109-3476-0

- Gerhard Hoffmann (Ed.): In the shadow of the sun - contemporary art of the Indians & Eskimos in Canada ; Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-89322-014-3

- Alma Houston (Ed.): Inuit Art - An Anthology ; Winnipeg MB 1988, ISBN 0-920486-21-5 pa. & ISBN 0-920486-22-3 vol .

- Odette Leroux, Marion E. Jackson & Minnie Audla Freeman (Eds.): Inuit Women Artists ; Vancouver 1994, ISBN 1-55054-131-5

- Derek Norton, Nigel Reading, & Terry Ryan: Cape Dorset Sculpture ; Vancouver & Seattle 2005, ISBN 0-295-98478-3

- Jill Oakes & Rick Riewe: The Art of Inuit Women - Proud boots, treasures made of fur ; Munich 1996, ISBN 3-89405-352-6

- George Swinton: Sculpture of the Inuit ; Revised and Updated 3rd Edition, Toronto 1999, ISBN 0-7710-8366-1

- Ansgar Walk: Kenojuak - life story of an important Inuit artist ; Bielefeld 2003, ISBN 3-934872-51-4

Web links

- Creartion - Art from the Arctic (German)

- Canadian Arctic Gallery - Gallery specializing in Canadian Inuit art (German / English)