Islam in Armenia

The Islam was for centuries alongside Christianity as one of the dominant religions on the territory of modern Armenia . Islam played a dominant role, especially from the 18th century with the establishment of the Yerevan Khanate .

Islamization

Islam began to invade what is now Armenia in the seventh century. Arab and later Kurdish tribes began to settle in Armenia after the first Arab invasions in the 7th century and played an important role in the country's political and social life in the following centuries. In order to strengthen their power and accelerate the Islamization process, the Arab caliphs settled Arab tribes in newly occupied areas. However, the Islamic-Muslim elements in Armenian-settled territories only gained strength with the conquest of the Turkish-born Seljuks in the 11th century . With the victory over the Byzantine Empire in the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the Seljuks brought large parts of Anatolia and Armenia under their control. With the Mongol-Tatar invasion in the 13th century and the Timur campaign in the 14th century, further Turkish tribes moved from Central Asia to Transcaucasia . Late 16th to early 17th century today's Armenia (especially the province of Yerevan) was additionally by four Turkic - Üstadschli , Alpout, Bayat and Qajar populated.

Cultural heritage

At the time of the Second Russo-Persian War (1826-1828), the population of the Yerevan (Yerevan) Khanate was 107,000 people, including 87,000 Muslims (mostly Azerbaijanis ). According to statistical data from the Tsarist administration published in 1831, i. H. were only published three years after the end of the war, the number of the Muslim population fell in a very short time to 50,000. Nevertheless, u. a. the city of Yerevan is predominantly Muslim. Almost all mosques in Yerevan that had been built up to the 16th century were destroyed during the Ottoman-Safavid wars when the city passed from hand to hand in the course of armed conflict. After the capture of the city by Russian troops in 1582 by was Turkish fortress built mosque on the instructions of General s Ivan Paskevich in a Russian Orthodox church converted. The church, named after Our Lady of Intercession , was consecrated on December 6, 1827. According to a statistical report by the Caucasian governor of the Tsarist Empire from 1870, there were a total of 269 Shiite Islamic places of worship in Yerevan Governorate, most of them in what is now Armenia.

Jean-Marie Chopin mentions eight mosques that Yerevan alone housed in the mid-19th century:

-

Abbas Mirza Mosque

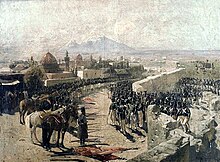

Yerevan with its mosques and minarets when they were captured by Russian troops in 1827. Painting by Franz Roubaud

Yerevan with its mosques and minarets when they were captured by Russian troops in 1827. Painting by Franz Roubaud - Mohammed Chan Mosque

- Sali-chan mosque

- Shah Abbas Mosque

- Novrus Ali bek Mosque

- Blue Mosque

- Sartip-chan mosque

- Hajji-Jafar-bek mosque

NIWoronow assumes a total of 60 mosques in the Ujezd Yerevan (a smaller administrative unit within the Yerevan governorate ). In his investigations, the archaeologist Philipp L. Kohl directed attention to the strikingly low number of Muslim cultural monuments in Armenia, although Muslims (Azerbaijanis, Persians , Kurds) had formed the vast majority here until the Treaty of Turkmechai : “Regardless of which Statistics on the demographic situation one also turns to, there is no doubt that a large number of material monuments of Islam should have existed in this region. Your almost complete absence today cannot be a coincidence. "

Azerbaijanis

At the turn of the 20th century, according to the Enziklopeditscheski slowar Brockhaus-Efron , there were 29,000 people in Yerevan , 4% Azerbaijanis, 48% Armenians and 2% Russians . In accordance with the anti-religious orientation of the Soviet ideology, after the establishment of communist rule in Armenia, many Islamic institutions were demolished and others, similar to the Armenian churches, were closed.

Through the decree “On the resettlement of cooperative farmers and other populations from the Armenian SSR to the Kura-Aras lowlands of the Azerbaijani SSR ” of December 23, 1947, around 150,000 Azerbaijanis lost their hometowns in Armenia between 1948 and 1953 and were moved to Central Azerbaijan forcibly relocated. Their houses were occupied by the Armenians from the diaspora (mostly from Syria , Iraq and Iran ). As a result, the number of Azerbaijani people in Armenia decreased dramatically. In Yerevan alone, their share fell to 0.7 percent in 1959.

When the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict flared up again at the end of the 1980s, around 200,000 Azerbaijanis, who were still living in Armenia in 1988 and thus formed the largest ethnic minority, fled to Azerbaijan or were expelled. In order to remove the remaining relics of the cultural and religious heritage of the Azerbaijanis from the cityscape of Yerevan, one of the last mosques used by Azerbaijanis in Vardanants Street 22 was demolished in 1990 because, as Thomas de Waal notes, it is not, unlike the Blue Mosque " Persian " could be classified. The designation of the Blue Mosque as Persian is interpreted as the linguistic elimination of the Azerbaijani past on the part of the Armenians, since most of the visitors to this place of worship were once Azerbaijani.

Kurds

The mass settlement of the Kurds in Armenia and other territories of the southern Caucasus by Ottoman sultans began at the end of the 16th century. As an ethnic minority, they only got political rights with the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Armenia in 1918. A representative of the Kurds was elected to the Armenian parliament. Kurdish officers served in the Armenian army and set up Kurdish volunteer units.

During the Stalinist purges , thousands of Kurds were forcibly deported from Armenia to Central Asia in 1937 . Between 1939 and 1959, many Kurds were listed by Soviet power as either Azerbaijanis or Armenians.

The negative consequences of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan also hit the Kurdish populated areas hard, especially on the Armenian side. Because of their cultural proximity to Azerbaijanis, Muslim Kurds in Armenia experienced discrimination and had to flee to Azerbaijan or the Russian North Caucasus in the late 1980s (a total of 18,000 people). With the conquest of the Azerbaijani cities of Laçın and Kəlbcər by Armenian troops, the Kurdish population was expelled from these provinces. 80 percent of them settled as internally displaced persons in refugee camps in Ağcabədi in Azerbaijan.

In 2001 there were just over 1,500 Muslim Kurds in Armenia.

present

Today Armenia is considered to be the most mono-ethnic country in the entire post-Soviet area , where Armenians make up 98 percent of the country's population, followed by Yazidis (1.2%) and other ethnic groups (0.8%). The proportion of Muslims is dwindlingly low and, according to the last census from 2011, is only 812 people (0.027% of the total population).

The Blue Mosque, which was restored between 1996 and 1999 on the initiative and with direct financial support of Iran, is the only surviving Shiite- Islamic institution in Armenia to survive the political turmoil of the 19th and 20th centuries. It is mainly used by Iranian citizens who work in Armenia or come as tourists and was leased to the Iranian state by the Armenian government in October 2015 for 99 years.

Individual evidence

- ↑ George Bournoutian: Eastern Armenia in the Last Decades of Persian Rule 1807-1828: A Political and Socioeconomic Study of the Khanate of Erevan on the Eve of the Russian Conquest . Undena Publications, 1982, ISBN 978-0-89003-122-3 , pp. 74 .

- ↑ Aram Ter-Ghevondyan: The Arab Emirates in Bagratid Armenia. Translated by Nina Garsoian . Ed .: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Lisbon 1976.

- ↑ Л.Б.Алаев, К.З.Ашрафян: История Востока. Восток в средние века. tape 2 . «Восточная литература» РАН, Москва 2002, ISBN 5-02-017711-3 .

- ↑ Dimitri Korobeinokov: Raiders and Neighbors. The Turks (1040-1304), in: The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire, ca. 500-1492 . Ed .: Jonathan Shepard. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008, pp. 692-727 .

- ↑ Л.Б.Алаев, К.З.Ашрафян: История Востока. Восток в средние века. tape 2 . «Восточная литература» РАН, Москва 2002, ISBN 5-02-017711-3 .

- ↑ Петрушевский Илья Павлович: Очерки по истории феодальных отношений в Азербайджане и Армении в XVI - начале XIX вв. Изд-во Ленинградского Государственного Ордена Ленина Университета им. А.А. Жданова, Ленинград 1949, p. 58. and 74 .

- ^ Richard Hovannisian: The Armenian People: From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century; Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century. St. Martin's Press, New-York 1997, ISBN 978-0-312-10168-8 , pp. 112 and 493 .

- ↑ electricpulp.com: EREVAN - Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved March 2, 2018 .

- ↑ Потто Василий Александрович: Кавказская война. Персидская война 1826-1828 гг. tape 3 . Издательство "Центрполиграф", Москва 2000, ISBN 5-4250-8099-9 , p. 359 .

- ↑ Главное Управление Наместника Кавказского: 1869. Кавказский календарь на 1870 год. Tипография Главного Управления Наместника Кавказского., Тифлис 1869.

- ↑ Chopin, Jean-Marie: Исторический памятник состояния Армянской области в эпоху ея присоединения к Российской импер импер импер . Типография императорский Академии Наук, Санкт -Петербург 1852, p. 468 .

- ↑ Н. И. Воронов .: Сборник статистических свѣдѣній о Кавказѣ. Императорское русское географическое общество. Кавказскій отдѣл., Санкт-Петербург 1869, p. 71 .

- ^ Philip L. Kohl / Clare P. Fawcett: Nationalism, Politics and the Practice of Archeology . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1995, ISBN 978-0-521-55839-6 , pp. 155 .

- ↑ Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона 1890-1907: Эривань. Retrieved March 2, 2018 (Russian).

- ^ Markus Ritter: The Lost Mosque (s) in the Citadel of Qajar Yerevan: Architecture and Identity, Iranian and Local Traditions in the Early 19th Century . Ed .: Iran and the Caucasus, Vol. 13, No. 2. 2009, p. 244 .

- ↑ Vladislav Zubok: A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev . University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill / London 2007, ISBN 978-0-8078-3098-7 , pp. 58 .

- ^ Lenore A. Grenoble: Language Policy in the Soviet Union . Springer Science & Business Media / Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003, ISBN 978-1-4020-1298-3 , p. 135 .

- ↑ International Protection Considerations Regarding Armenian Asylum-Seekers and Refugees. (No longer available online.) United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2003, archived from the original on April 16, 2014 ; accessed on March 3, 2018 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. 10th-year of Anniversary Edition, Revised and Updated . New-York University Press, New-York / London 2013, pp. 80-81 .

- ↑ Lia Evoyan / Tatevik Manukyan: Religion as a factor in Kurdish identity discource in Armenia and Turkey . In: Ansgar Jödicke (Ed.): Religion and Soft power in the South Caucasus . 2017, ISBN 978-1-138-63461-9 , pp. 150 .

- ↑ Гажар Аскеров: Курдская диаспора в странах СНГ . Бишкек 2005, p. 48 .

- ^ Lokman I. Meho and Kelly L. Maglaughlin: Kurdish Culture and Society: An Annotated Bibliography . Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut / London 2001, ISBN 0-313-31543-4 , pp. 22 .

- ↑ Alexandre Bennigsen and S. Enders Wimbush: Muslims of the Soviet Empire. A guide . C. Hurst and Company, London 1985, ISBN 1-85065-009-8 , pp. 210 .

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War . New-York University Press, New-York / London 2003, ISBN 0-8147-1944-9 , pp. 304 .

- ↑ Azerbaijan. Seven Years of Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. Human Rights Watch / Helsinki, December 1994, accessed March 3, 2018 .

- ↑ Ариф Юнусов: Этнический состав Азербайджана (по переписи 1999 года). March 12, 2001, Retrieved March 3, 2018 (Russian).

- ^ Europe MRG Directory. Armenia. Minority Rights Group International. World Directory of Minorities, accessed March 3, 2018 .

- ^ The Major Ethnic Groups Of Armenia . In: WorldAtlas . ( worldatlas.com [accessed March 3, 2018]).

- ↑ Sevak Karamyan: Armenia. Muslim Populations . In: Jørgen Nielsen, Samim Akgönül, Ahmet Alibašić, Egdunas Racius (eds.): Yearbook of Muslims in Europe . tape 6 . Brill, Leiden / Boston 2014, p. 36 .

- ↑ Антон Евстратов: Голубая мечеть в Ереване - центр городской истории и персидской культуры. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on March 6, 2018 ; Retrieved March 3, 2018 (Russian). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.