Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is a conflict of states Armenia and Azerbaijan over the region of Nagorno-Karabakh in the Caucasus. The conflict first appeared in the modern era on the independence of the two states after 1918 and broke out again during the final phase of the Soviet Union from 1988. As a result, the Artsakh Republic (Nagorno-Karabakh Republic until 2017) declared itself independent, but has not yet been recognized internationally by any member state of the United Nations .

causes

prehistory

In ancient times, the Nagorno-Karabakh region belonged alternately to the states of Armenia and Albania . In 469 it became a province of the Sassanid Empire and then repeatedly part of changing empires. Christianity reached the region at the beginning of the 4th century. The oldest churches and monasteries in Nagorno-Karabakh, such as Amaras Monastery , date from this period. From the early Middle Ages the region was ruled by various Armenian princely houses. In the 13th century the Mongols conquered the country, which were replaced by the Turkic speaking Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu . These give the region the name Karabach , "Black Garden". This region largely comprised the plains between the Kura and Araxes rivers and was therefore much larger than today's Nagorno Karabakh. From the 18th century - before Karabakh was part of Persia - the rivalry between the Ottoman Empire , Russia and Persia determined the region. As the pressure from Persia on the Armenian Christians increased, Catherine II of Russia issued letters of protection and thus privileged Armenians for trade and later administration. Therefore Azerbaijanis still accuse the Armenians of collaboration .

As a result of the Second Russo-Persian War , Nagorno-Karabakh came under Russian rule in 1805. A survey of the population of the Karabakh Khanate from 1823 showed that most of the villages in the mountainous regions of what is now Nagorno-Karabakh were Armenian. In the mountainous areas, where the five Armenian principalities of Karabakh had existed until the beginning of the 18th century , the Armenian Christians made up the majority of the population, the Muslim Azeris a large minority. For the area of the entire Karabakh between Kura and Aras, however, Rüdiger Kipke speaks with reference to the statistical data of the Russian administration on the population from the year 1823 of a total of slightly more than 20,000 families, of which 4,366 or 21.7% are Armenian and the rest are Muslim (Azerbaijani). The Caucasus expert Johannes Rau spoke of 18,000 Armenians who lived in Karabakh before the 1830s.

Under Russian rule, the Christian Armenians were given preferential treatment over the Muslim Azerbaijanis - at this time the Russian authorities, like many Turkish-speaking ethnic groups, generally referred to them as Tatars - which was expressed, for example, in extensive church and school autonomy. In addition, mostly Armenians were hired as civil servants. The Russians encouraged the settlement of Armenians from Muslim countries. In the 19th century, 40,000 Armenians from Persia and 84,000 from the Ottoman Empire immigrated to Russia. Karabakh belonged to changing administrative districts in the Russian Empire and in addition to Armenians, Russians, Ukrainians and Germans were also settled. The areas were mostly divided according to military, administrative and economic aspects with the aim of allowing the ethnically heterogeneous population to merge with the Russian. The Yelisavetpol Governorate , to which Nagorno-Karabakh belonged, had become the most ethnically and religiously heterogeneous by 1917.

After the genocide of the Turks against the Armenians in 1915/1916 in the Ottoman Empire, there was another wave of immigration to Nagorno-Karabakh and increasingly stronger conflicts between rural Azerbaijanis and urbanized Armenians. This was compounded by the emerging land and water scarcity in the region. The different customs, such as blood revenge and clan liability among some of the Azerbaijanis - but also among a minority of Armenians - and their proximity to the Turks, from whom many Armenians had fled, increased mutual mistrust. Already from 1896 to 1905/1906 these conflicts had culminated in armed conflicts between the ethnic groups. In March 1918 there were pogroms against Azerbaijanis , followed by anti-Armenian pogroms in September 1918 in Baku and in 1920 in Shusha , which killed more than 30,000 Armenians.

Conflicts between Armenians and Azeris

The Azeri living in the Armenian Soviet Republic made up the largest minority in 1988 with 5% of the population. They were traditionally involved in agriculture and the grocery trade and therefore had a great influence on the Green Bazaar . This led to resentment towards the Azerbaijani minority, especially when there was a food shortage. The orientalist Eva-Maria Auch also names different state traditions, historical experiences with the Ottoman Empire and Turkey as well as Russia and especially the Russian and Soviet nationality politics as causes of the conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijanis.

development

Conflict 1918 to 1923

After Armenia and Azerbaijan declared independence from Russia in 1918, both republics laid claim to Nagorno-Karabakh. Armenia justified this with the geographical and ethnic contrast to Lower Karabakh, Azerbaijan with the inseparability of the geographical area and the summer meadows of the Muslim nomads in Nagorno Karabakh. After bloody clashes on both sides, in which Azerbaijan was supported by Turkey and Great Britain, a Provisional Agreement was signed on August 22, 1919 , which granted Azerbaijan to all of Karabakh on the condition of cultural and administrative autonomy for the Armenians.

After the proclamation of Soviet republics in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh in 1920, a peaceful solution was promised. Nagorno-Karabakh voluntarily declared that it belonged to Azerbaijan. In December, Stalin announced that Armenia would renounce Nagorno-Karabakh, Nakhichevan and Sangesur . Nevertheless, there was military activity by the Dashnaks in the region. A compromise was reached in the Moscow Treaty of March 16, 1921, in which Turkey was also a party: the Soviet side took over the provinces of Kars , Ardahan and Ujesd Surmalu (around today's village of Sürmeli, Tuzluca district ) Turkey from, Nakhchivan became an autonomous republic in Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh (with an Armenian population of 94% in 1923) remained part of Azerbaijan until a referendum. Nagorno-Karabakh became an autonomous region of the Azerbaijani SSR on July 7, 1923 by decree . The Armenians, as the vast majority of the population, were dissatisfied with this decision.

The conflict broke out again after 1985

By 1985, the Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh referred to only limited autonomy in three memoranda in 1962, 1965 and 1967 and called for annexation to Armenia. Another memorandum was issued in 1986/1987, and Azerbaijan responded with a reference to the Azerbaijanis living in Armenia, who had no special rights. In 1989, of the approximately 188,000 people in Nagorno-Karabakh, 73.5% were of Armenian origin and 25.3% were Azerbaijanis. In 1987 and 1988, delegations from Nagorno-Karabakh pushed for a solution to the conflict in Moscow, and from February 12, 1988 demonstrations took place in Stepanakert, and later in other parts of Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia. According to the authorities, 4,000 Azeris had been expelled from Armenia by February 18. Soon after, a meeting of representatives of the people of Karabakh voted for the annexation to Armenia and the Russian Secretary of the General Party Committee was replaced by the Armenian Genrich Poghosjan.

After Azerbaijani refugees reported bloody riots in Nagorno-Karabakh in the city of Sumqayıt near Baku at the end of February , a pogrom broke out against the Armenians living there , in which 26 Armenians and six Azeris were killed. Since the security organs did not intervene, both sides called for self-protection. In March 1988, the Central Committee of the CPSU decided on an economic and social program for Nagorno-Karabakh, a border revision was rejected. In the following months, Azeris continued to be expelled from Armenia, there were further riots and strikes and the Central Committee secretaries of both republics were dismissed. On July 12, the Karabach Regional Soviet decided to rename it to the Artsakh Autonomous Region and to leave Azerbaijan. As a result, Azerbaijan imposed a traffic blockade and was supported by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, who sent a special envoy in the form of A. Wolsky.

A state of emergency was declared on Agdam and Stepanakert on September 21, 1988 and Nagorno-Karabakh was declared a special area. A non-stop meeting was held in Baku from November 17 to December 5, and over 200 operational groups were set up to support the Azerbaijani Popular Front (NFA), an opposition movement. When the military evacuated Lenin Square, three people died. In the city of Kirovabad (now Gəncə) there was another pogrom against Armenians living there in November 1988 , in which more than 130 Armenians were reportedly killed and over 200 wounded. On January 12, 1989 Nagorno-Karabakh was subordinated to a special committee and thus directly subordinate to the Soviet headquarters and the regional authorities were suspended. From January, the Armenians fled Azerbaijan. By September, there were demonstrations and strikes by the NFA, which, in addition to control of Nagorno-Karabakh, demanded participation in the government and the withdrawal of the Soviet army for Azerbaijan. When she first participated in the Azerbaijani Supreme Soviet, Nagorno-Karabakh was established as part of Azerbaijan by law. Border changes can only be made by means of a referendum, which has been outstanding since 1923. By September 1989, 180,000 Armenians had fled Azerbaijan and around 100,000 Azeris had fled Armenia. The Supreme Soviet of Armenia appealed to Moscow to end the economic blockade in Azerbaijan, which by September 1989 caused damage of 150 million rubles. On September 25, the Soviet Interior Ministry took over the duties of the civil authorities in Nagorno-Karabakh. On October 5th, the Soviet Army took control of the transport routes between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

On November 29, 1989, the Nagorno-Karabakh special administration was lifted, whereupon there were renewed demonstrations with fatalities. In December and January there were attacks on the borders of the Autonomous Republic of Nakhichevan with Iran and Turkey, a United Azerbaijan is called for. After the government had promised to make travel easier and land use near the border, the situation calmed down. After the Supreme Soviet of Armenia had declared the unification of Karabakh with Armenia on December 1, 1989, protests from the Azerbaijani side followed and on January 13 and 14, 1990 pogroms against Armenians in Baku , Xanlar , Shahumjan and Lənkəran with more than 90 fatalities. Martial law was declared on January 15 in Karabakh and neighboring areas. After a general strike was proclaimed in Baku, Soviet tanks rolled into the city on January 20, causing 150 deaths and a state of emergency was declared. Nakhichevan and the Supreme Soviet of Azerbaijan protested. Russian and Armenian families fled Baku, up to that point a total of 500,000 people had fled. Up until August, there were further attacks on Armenian and Azerbaijani villages, primarily by paramilitary groups. In Azerbaijan, the OMON , the interior ministry militia, joined by many refugees from Armenia. After Armenia and Azerbaijan declared independence, Nagorno-Karabakh declared its independence as the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic on September 3, 1991, but attacks continued in the border areas. In November 1991 an attempt by Russia and Kazakhstan to mediate between Armenia and Azerbaijan failed. On November 26, Azerbaijan raised the autonomy of Nagorno-Karabakh and divided the Autonomous Region in the districts Kälbädschär (partly outside Nagorno-Karabakh lying), Shushi , Tärtär , Chankändi , Khojali and Chodschavänd on. The blockade of energy supplies in Armenia was maintained.

War 1992 to 1994

| date | 1992 to 1994 |

|---|---|

| place | Nagorno-Karabakh |

| output | armistice |

| consequences | Armenia occupies Nagorno-Karabakh |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

At the beginning of 1992 there were further mass murders in Azerbaijani and Armenian villages. One in February by the President of Azerbaijan Mutalibov submitted peace plan, which provided for the withdrawal of all troops and a cultural autonomy for Nagorno-Karabakh, was not negotiated after the night of 26 to 27 February, the village of Khojaly under unclear circumstances, Armenian irregulars had been handed over and several hundred people were murdered. After this so-called Khodjali massacre in Azerbaijan, a new government was formed in Azerbaijan. On April 10, 1992, the Maraga massacre followed , in which Azerbaijani armed forces attacked the village of Maraga and murdered at least 45 Armenians and kidnapped up to 100 women and children.

In March 1992, Armenian militants invaded large parts of Nagorno Karabakh and also advanced on Azerbaijani territory outside the disputed region, so the city of Agdam was under fire. As a result, a separate army was built in Azerbaijan and allies were sought in Turkey and other Muslim states. A Chechen unit under Shamil Salmanovich Basayev was one of the supporters of the Azerbaijanis . Shusha was the main base of Azerbaijanis: From here, the deeper was Stepanakert taken effectively under attack. But even Basayev's troops could not prevent that on May 8 and 9, 1992, Armenian units with Şuşa captured the last city of Nagorno-Karabakh. Basayev was one of the last to leave the position before the fall of the city. Then the Karabakh army from militia associations was founded. On May 18, the Armenians took the city of Laçın and thus the road connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. An offensive by the Azerbaijani army from Goranboy followed in June , during which northern parts of Nagorno-Karabakh were occupied. In winter the fighting was largely stopped because of the poor supply situation and the geographic location.

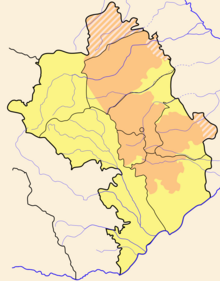

After the Azerbaijani army attacked Nagorno-Karabakh in Kəlbəcər Rayon , which lies between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, in March 1993 , the Armenian Army intervened and the district was occupied by the Armenian Army and the Karabakh Army until April 3. The districts of Ağdam, Füzuli , Cəbrayıl and Qubadlı were occupied from April to August 1993 through offensives by the two armies . By October the Zəngilan district was taken.

A ceasefire agreement came into force on May 12, 1994. During the war, the troops of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, together with the Armenian army, were able to take control of large parts of the area claimed by Nagorno-Karabakh. They also occupied most of the Azerbaijani districts of Ağdam, Cəbrayıl, Füzuli, Kəlbəcər, Laçın, Qubadlı and Zəngilan outside the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region. Between 25,000 and 50,000 people died in the war and previous conflicts, and over 1.1 million were displaced on both sides from Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh and the rest of Azerbaijan.

Diplomatic activities

The Minsk Group, founded in March 1992 with 13 participating states, observed the conflict but was unable to mediate. Representatives of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic remained excluded from the group. In 1993 the UN passed four resolutions (Nos. 822 , 853 , 874 , 884 ) on the conflict, but they had no effect. In September 1993, Turkey broke off diplomatic relations with Armenia due to the conflict and closed the common border. The Armenian-Turkish relations have not normalized since then.

Development since 1994

Negotiations took place for a long time after the armistice. Azerbaijan insisted on the return of Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia on its independence from Azerbaijan. The OSCE regularly tried to mediate between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The OSCE proposed a joint state of Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh, in which the disputed region is no longer subordinate to the government in Baku.

In 1999 tensions arose again as a result of the war in Kosovo , as Armenia saw its position as strengthened and threatened war. The population of Nagorno-Karabakh, like those of Kosovo, is entitled to leave Azerbaijan under the right to self-determination. In a possible war, Armenia hoped for help from Russia, which it had previously equipped with, and Azerbaijan from Turkey and NATO, to which offers to use an Azerbaijani air base were made after the Armenian threat.

After 2000, the two countries came closer together and both sides emphasized the willingness to find a solution, but both sides stuck to their positions. Meanwhile, the economy in Karabakh recovered from the war, mainly with investment from low taxes and donations from Armenians living in Europe and America.

The Republic of Artsakh was able to stabilize internally and a modest tourism developed. The 140,000 inhabitants are almost exclusively ethnic Armenians. 20,000 soldiers of the Armenian army hold the ceasefire line with Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan's President Ilcham Aliyev has regularly increased his military spending and stressed that he wanted to restore the country's territorial unity . There are always border conflicts and clashes on the Azerbaijani and Armenian sides.

In July 2007, Azerbaijani President Aliyev threatened his own military strength and another war if Armenia did not voluntarily vacate Nagorno-Karabakh. In Yerevan , Baku's uncompromising stance was criticized and it was said that there was no alternative to a peaceful solution. However, negotiations between the two sides, including Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh, began for the first time at the same time. The threats from President Aliyev were sometimes described as domestic political maneuvers, and members of the negotiating delegations saw no possibility of a military solution to the conflict. In connection with the negotiations on the future status of Kosovo , the Russian side threatened in the summer of 2007 that, if its interests were not taken into account, an answer would follow in the republics of Transnistria , Abkhazia , South Ossetia and Nagorno-Karabakh. In the course of the negotiations, the Minsk Group proposed a solution. Armenia should withdraw from the occupied territories outside Nagorno-Karabakh, allow the return of Azerbaijani, peacekeeping forces should be stationed and reconstruction aid should be provided, and a referendum should later be held on the status of Nagorno-Karabakh.

On March 4, 2008, the worst clashes on the armistice line since 1994 took place. Up to twelve Armenian and eight Azerbaijani soldiers were killed. As part of the informal CIS summit in Saint Petersburg in 2008, the presidents of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, and Armenia, Serzh Sargsyan , met on June 6, 2008 . After further mediation by the Russian President Dmitri Medvedev , the presidents of both states issued a declaration in Moscow on November 2, 2008 that they would resolve the conflict peacefully and in accordance with international law. Further meetings were planned to work out a political solution. Russia offered to act as a guarantor for a compromise solution that would come about in the negotiations. The negotiations that took place until 2011 were unsuccessful, however, after the last meeting of presidents in Kazan in July 2011, mediation was abandoned.

After the failed mediation, both parties to the conflict began again to arm for war. While Armenia expanded its military cooperation with Russia in the form of joint exercises and arms purchases and purchased smaller amounts of armaments from other countries, Azerbaijan built up military cooperation and supply relationships with Turkey, Ukraine and, in particular, Israel in addition to the traditional, likewise expanded arms deliveries to Russia. The latter supplied 60% of Azerbaijani arms imports from 2015 to 2019, including state-of-the-art weapons such as drones, and air and missile defense technology. In July 2014, battles broke out again for the first time after the failed negotiations. The conflicting parties accused each other of sending reconnaissance and sabotage units across the ceasefire line. The Azerbaijani Ministry of Defense said that two Armenian and ten Azerbaijani soldiers were killed. The Armenian side reported that 14 Azerbaijani soldiers were killed and one Armenian soldier was killed.

Armed clashes broke out again between April 2 and 5, 2016. According to Armenian sources, 92 Armenian soldiers and one child died after Azerbaijani forces launched an attack with tanks, artillery shelling and helicopter gunships. According to Azerbaijan, 31 Azerbaijani soldiers and two civilians died after Armenian forces fired artillery and grenade launchers. The fighting was the toughest since the 1994 armistice, but it did not result in any significant territorial changes. According to the Armenian President Sargsyan, the Armenian side lost about 800 hectares. Azerbaijan's President Aliyev said Azerbaijan had recaptured 2,000 hectares. The Russian Defense Minister Shoigu phoned his Azerbaijani and Armenian counterparts and urged both to ease the tensions. An OSCE spokesman also expressed grave concern about the violation of the ceasefire. The Turkish President Recep Erdogan assured then Azerbaijan Turkey's support to: We will support Azerbaijan to the end. In an interview, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev expressed concern about the recent outbreak of violence, but defended Russian arms deliveries to both parties to the conflict. "If we don't deliver weapons, other sellers would take this place."

In the summer of 2017, there was an attack by Azerbaijan to Armenian position by a Kamikaze - drone .

Acts of war in 2020

In July 2020, fighting broke out between the armed forces of Armenia and Azerbaijan on the border between the two states north of Nagorno-Karabakh, between Tovuz and Tavush . This resulted in deaths and injuries on both sides, including civilian victims. In the following weeks there were repeated clashes between the two sides, including on the truce line in Nagorno-Karabakh.

On September 27, 2020, the fighting escalated in a large-scale attack by Azerbaijan on the internationally unrecognized Republic of Artsakh from the south-east and north. The skirmishes quickly turned into the most difficult and bloodiest battles since the 1990s. Both the Artsakh Republic and Armenia announced a state of emergency and called for general mobilization , as did Azerbaijan for some of its regions. Armenia and Azerbaijan accused each other of starting the aggression. According to French President Macron and the Russian government, the Turkish government under Recep Erdoğan has sent mercenaries from Syria and Libya to the area on the Azerbaijani side. Various other sources also indicated that Turkey recruited between 850 and 4000 mercenaries in Syria and may have transported them, as well as drones, to Azerbaijan in the Nagorno-Karabakh area from the end of September 2020. As of October 8, 350 Armenian soldiers were killed, according to the armed forces of Armenia . The Azerbaijani armed forces did not provide any information about their own losses. Armenia announced that Arzach's capital, Stepanakert , had been fired at with rockets again. The authorities of the Artsakh Republic announced that between 70,000 and 75,000 people (90% of whom were women and children) had fled the Nagorno-Karabakh region . According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights , 72 Syrian mercenaries were killed in the conflict on the Azerbaijani side (as of October 4). According to the Azerbaijani news agency Azeri Press Agency, as of October 8, 31 civilians have been killed and 154 civilians have been injured in Armenian attacks. The Armenian news agency Armenpress reported 22 civilians dead and 95 civilians injured in attacks by the Azerbaijani side. A ceasefire organized in October 2020 by Armenia's protecting power Russia was broken less than 24 hours later.

Positions on the Conflict

Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh

Even during the Soviet era, Armenia repeatedly accused Azerbaijan of violating Nagorno-Karabakh's autonomy. The government of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic under Gurkassyan did not believe that there could be any real autonomy for Nagorno-Karabakh in Azerbaijan, as this had already been violated during the Soviet era and in 1991 Azerbaijan revoked Nagorno-Karabakh's autonomy. The Armenians in both Armenia and the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic see themselves as one nation. A return of the Azerbaijani refugees is rejected by the government in Stepanakert and Armenia demands the independence of Nagorno-Karabakh from Azerbaijan and more willingness to compromise on the part of Baku. The then Armenian President Robert Kocharyan declared in 2003 that Azerbaijanis and Armenians could not live together in one state because they were "ethnically incompatible". For this statement, Kocharyan was criticized by the then Secretary General of the Council of Europe Walter Schwimmer .

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan has denied allegations that Nagorno-Karabakh's autonomy was not preserved during the Soviet era. After the 1992-1994 war, Azerbaijan continued to claim Nagorno-Karabakh as Azerbaijani territory. Nagorno-Karabach's independence is not recognized, only extensive autonomy. In addition, the return of the occupied areas populated by Azerbaijanis is required. The Azerbaijani government threatened another war several times, but there is also resistance within Azerbaijan to attempts to find a military solution to the conflict. The oil and gas companies that have invested in Azerbaijan see their investments at risk from another war.

International

The Council of Europe regards Nagorno-Karabakh as an area controlled by “separatist forces”. In Resolution No. In 2216, the European Parliament welcomed the talks between the presidents of Armenia and Azerbaijan and called on the parties to the conflict to intensify their peace efforts and to guarantee all refugees - be they Armenians or Azerbaijanis - the right to return to their homes. At the same time, it called for international armed forces to be stationed until the status of Nagorno-Karabakh was clarified, parallel to the withdrawal of the Armenians from the occupied Azerbaijani territories. The United Nations Security Council has confirmed in three declarations that Nagorno-Karabakh is part of Azerbaijani territory. So far, no state has recognized the independence of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic.

In September 2011, the Foreign Minister of Uruguay, Luis Almagro, announced that his government had started a process for the official recognition of the "Nagorno-Karabakh Republic".

Significance of the conflict for the states involved

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict hampered the stabilization of the first independent republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan at the beginning of the 20th century and allowed third-party interference, particularly Turkey and Russia, previously the Soviet Union. It became an integral part of the national consciousness of both nations, that of Armenia after the unsatisfactory compromise of 1921 and that of Azerbaijan after the conflict broke out again in the late 1980s. In addition, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was one of the causes of the growing opposition in the participating Soviet republics and the collapse of the USSR in this region.

literature

- Eva-Maria Also : "Eternal Fire" in Azerbaijan - a country between perestroika, civil war and independence. Reports of the Federal Institute for Eastern and International Studies, 8–1992.

- Rüdiger Kipke : The Armenian-Azerbaijani relationship and the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-531-18484-5 .

- Otto Luchterhandt: The right of Nagorno-Karabagh to state independence from the point of view of international law. In: AVR 31 (1993), pp. 30-81.

- Johannes Rau: The Nagorny-Karabakh Conflict (1988-2002). Publishing house Dr. Köster, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-89574-510-3 .

- Manfred Richter (ed.): Armenian Nagorno-Karabakh / Arzach in the struggle for survival. Christian art - culture - history. Edition Hentrich, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-89468-072-5 .

- Vahram Soghomonyan (ed.): Solution approaches for Nagorno-Karabakh, Arzach: self-determination and the way to recognition. Baden-Baden: Nomos 2010, ISBN 978-3-8329-5588-5 .

- André Widmer: The forgotten conflict - Two decades after the Nagorno-Karabakh war = The forgotten conflict. A. Widmer, Gränichen 2013, ISBN 978-3-033-03809-7 .

Web links

- Armenia and Azerbaijan - Nagorno-Karabakh: The Forgotten Conflict , Der Tagesspiegel, November 23, 2009

- Michael Ludwig: Threatening lines of defense. Nagornyj Karabakh conflict. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . May 25, 2011, accessed on May 26, 2011 (background report on the situation in spring 2011).

- Uwe Halbach: Nagorny-Karabach. Dossier on internal conflicts in: BPB. April 11, 2016

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Eva-Maria Also: "Eternal fire" in Azerbaijan - a country between perestroika, civil war and independence . Reports of the Federal Institute for Eastern and International Studies, 8–1992.

- ↑ George A. Bournoutian: A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-E Qarabagh , Costa Mesa 1994, p. 18.

- ↑ Rüdiger Kipke: The Armenian-Azerbaijani Relationship and the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict . 1st edition. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-531-18484-5 , pp. 18 .

- ↑ Johannes Rau: Nagorno-Karabakh in the history of Azerbaijan and the aggression of Armenia against Azerbaijan . 1st edition. Dr. Köster, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-89574-695-6 , pp. 151 .

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Black Garden - Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York University Press, 2003.

- ^ Playing the "Communal Card": Communal Violence and Human Rights . Human Rights Watch . New York, 1995. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Eva-Maria Also : Nagorno Karabakh - War for the «black garden» in the Caucasus - history-culture-politics . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2010 (2nd edition).

- ^ Armenia - With Open Cards , arte , February 20, 2007.

- ↑ Eva-Maria Also: Azerbaijan: Democracy as Utopia? . Reports of the Federal Institute for Eastern and International Studies, 1994.

- ↑ Azerbaydzhan: Hostages in the Karabakh conflict: Civilians Continue to Pay the Price ( Memento of October 2, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 40 kB). Amnesty International . P. 9, April 1993. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

- ↑ Flaming anger . In: Der Spiegel . No. 12 , 1992 ( online ).

- ↑ Thomas De Waal (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press, pp. 177-179. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7 .

- ^ How Turkey maneuvers between Russia and the West , Spiegel Online, September 12, 2008.

- ↑ Despite NATO exercise: Turkey keeps the border with Armenia closed . RIA Novosti . August 27, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ↑ a b New war in the Caucasus? In: Der Spiegel . No. 14 , 1999 ( online ).

- ^ State without recognition , Deutschlandfunk über Nagorno Karabakh, September 1, 2006.

- ^ Resurrection from ruins , Stephan Orth, Spiegel Online, February 19, 2008.

- ^ A b Solution to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in sight , NZZ Online, November 2, 2008.

- ↑ a b c Autonomy means war , interview with Arkadij Gurkassjan, Spiegel Online, July 9, 2007.

- ↑ a b c d Nagorno-Karabakh: Is Peace Possible in the Near Future? ( Memento of October 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), Behrooz Abdolvand and Nima Feyzi Shandi, Eurasian Magazine, July 31, 2007.

- ↑ Karabakh casualty toll disputed , BBC, March 5, 2008.

- ^ Nagorno-Karabakh conflicting parties advocate a political solution , RIA Novosti, November 2, 2008.

- ↑ Russia offers to guarantee the Nagorno-Karabakh settlement , RIA Novosti, October 31, 2008.

- ↑ Karabakh summit in Kazan did not bring about a breakthrough. (No longer available online.) RIA Novosti , June 25, 2011, archived from the original ; Retrieved August 3, 2014 .

- ↑ Uwe Halbach, Franziska Smolnik: The dispute over Nagorno-Karabakh - specific features and the conflicting parties . Science and Politics Foundation , February 2013. P. 30 PDF .

- ↑ Canan Atilgan: The conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh: New solutions required. Konrad-Adenauer -Stiftung, June 12, 2012, accessed on October 1, 2020 .

- ^ A b Andranik Eduard Aslanyan: Energy and geopolitical actors in the South Caucasus. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in the field of tension between interests (1991-2015). Springer-Verlag, 2019, p. 116.

- ↑ Nothing is normal in Karabakh (section: Armenian for two thousand years ) Le Monde diplomatique of December 14, 2012, accessed on September 28, 2020.

- ↑ Alexander Sarovic: These countries sell the most weapons. Spiegel-Online, March 9, 2020, accessed October 1, 2020 .

- Jump up again to Nagorno-Karabakh. Tagesschau.de, August 2, 2014, accessed on August 3, 2014 .

- ↑ Министерство обороны: Потери армянской стороны составили 92 человека. In: news.am. Retrieved May 5, 2016 .

- ↑ Минобороны Азербайджана назвало количество погибших в Нагорном Карабахе. In: www.aif.ru. Retrieved May 5, 2016 .

- ↑ Генпрокуратура Азербайджана: в Карабахе погибли двое мирных граждан. In: РИА Новости. Retrieved May 5, 2016 .

- ↑ Google. Retrieved February 16, 2017 .

- ↑ Ильхам Алиев: Азербайджан вернул 2000 гектаров оккупированных территорий - Minval.az . In: Minval.az . June 3, 2016 ( minval.az [accessed February 16, 2017]).

- ↑ Nagorno-Karabakh violence: Worst clashes in decades kill dozens. BBC News, April 3, 2016, accessed April 4, 2016 .

- ↑ Nagorno-Karabakh: Turkey pledges support to Azerbaijan . In: The time . ISSN 0044-2070 ( zeit.de [accessed April 12, 2016]).

- ↑ Радио «Свобода»: Медведев высказался за поставки оружия Армении и Азербайджану . In: ГОЛОС АМЕРИКИ . ( golos-ameriki.ru [accessed September 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Israeli Firm Loses Kamikaze-drone Export License After Complaint It Carried Out Live Demo on Armenian Army. Retrieved August 30, 2017 .

- ↑ Кавказский Узел: Armenia claims 39 wounded and four killed persons since conflict escalation. July 17, 2020, accessed on July 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Кавказский Узел: Azerbaijan and Armenia claim shelling attacks and downed drones. July 15, 2020, accessed on July 18, 2020 .

- ^ Azerbaijan launches new offensive against Karabakh, occupies border areas. Retrieved October 4, 2020 (Catalan).

- ^ Armenia announces general mobilization after heavy fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh. Die Welt, September 27, 2020, accessed on September 27, 2020 .

- ^ Deutsche Welle (www.dw.com): Macron: Jihadists from Syria are fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh | DW | 01/10/2020. Accessed October 5, 2020 (German).

- ↑ Maximilian Popp, Guillaume Perrier, Daham Alasaad, DER SPIEGEL: Syrian mercenaries in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict: Erdogan's shadow warriors - DER SPIEGEL - politics. Retrieved October 5, 2020 .

- ^ WORLD: Nagorno-Karabakh: 850 Syrian mercenaries are supposed to support Azerbaijan . In: THE WORLD . October 3, 2020 ( welt.de [accessed October 4, 2020]).

- ↑ DER SPIEGEL: Nagorno-Karabakh: Armenia accuses Turkey of sending 4,000 fighters from Syria - DER SPIEGEL - politics. Retrieved October 5, 2020 .

- ↑ DER SPIEGEL: dead and injured again in new fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh - cathedral damaged - DER SPIEGEL - politics. Retrieved October 9, 2020 .

- ^ Deutsche Welle (www.dw.com): Half of Nagorno-Karabakh's population displaced by fighting | DW | 07.10.2020. Retrieved October 9, 2020 (UK English).

- ^ Nagorno-Karabakh battles | 72 Syrian mercenaries killed since Turkey threw them into raging conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia • The Syrian Observatory For Human Rights. In: The Syrian Observatory For Human Rights. October 4, 2020, accessed October 9, 2020 (American English).

- ↑ APA.az: 31 civilians killed, 154 injured as a result of Armenian provocations. October 8, 2020, accessed October 9, 2020 (Azerbaijani).

- ↑ 22 civilians killed, 95 injured from the Armenian side as a result of Azerbaijani aggression. Retrieved October 9, 2020 .

- ↑ DER SPIEGEL: Nagorno-Karabakh: New fighting after the start of the ceasefire - DER SPIEGEL - Politics. Retrieved October 10, 2020 .

- ↑ Nagorno-Karabakh: Timeline Of The Long Road To Peace . In: RadioFreeEurope / RadioLiberty . Nkao February 10, 2006 ( rferl.org [accessed September 14, 2015]).

- ↑ Texts adopted - Thursday, 20 May 2010 - The need for an EU strategy for the South Caucasus - P7_TA (2010) 0193. Accessed December 8, 2017 .

- ↑ "Uruguay May Recognize Nagorno-Karabakh Republic" (English), September 9, 2011. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Uruguay apuesta por la independencia o unión con Armenia de Nagorno Karabaj" (Spanish), September 9, 2011. Accessed February 20 2012th