Julia Maesa

Julia Maesa ( Latin Iulia Maesa, Greek Ἰουλία Μαῖσα; † probably around 224/225 in Rome) was the sister-in-law of the Roman emperor Septimius Severus (193-211) and grandmother of the emperors Elagabal (218-222) and Severus Alexander (222-235 ). After the descendants of Septimius Severus died out in 217, she helped her two grandchildren successively to become emperor, thus ensuring the continuation of the Severan dynasty . Since Elagabal and Severus Alexander were still young people when they took office, she exercised considerable influence. During the violent change of rule in 222, when Elagabal was overthrown and murdered and replaced by his cousin Severus Alexander, Julia Maesa and her daughter Julia Mamaea played a key role. During this crisis, under difficult circumstances, she succeeded in stabilizing the rule of her family.

Life

origin

Maesa came from a very rich and respected family in the Syrian city of Emesa , today's Homs . In this family the office of high priest of the sun god Elagabal was hereditary. Maesa's father Julius Bassianus held this office. The Elagabal cult played a central role in the religious life of the Emesians.

Relationship with the imperial family

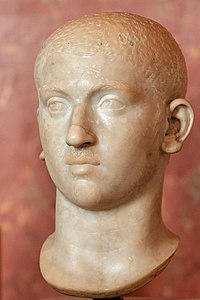

Glyptothek , Munich

In 187, the African Septimius Severus , who was then governor of the province of Gallia Lugdunensis , married Maesa's sister Julia Domna . In the turmoil of the " second year of the Four Emperors " in 193, Severus was proclaimed emperor by his troops in Upper Pannonia , where he was then governor. He was able to take Italy quickly, and in the following years he asserted himself in civil wars against his rivals.

With Severus' coming to power, his sister-in-law's clan also came to the center of power. Maesa spent the reign of Septimius Severus (193-211) and that of his son and successor, her nephew Caracalla (211-217), in the imperial palace in Rome or in the vicinity of her frequently traveling imperial sister Julia Domna. She was married to the Syrian Gaius Julius Avitus Alexianus and had two daughters; the older one was called Julia Soaemias , the younger Julia Mamaea. Avitus came from the knighthood . Soon after he came to power, Severus made sure that his sister-in-law Maesa's husband was admitted to the Senate . Later Avitus became governor of the province of Raetia . Around 198/200 he was a suffect consul . 208-211 he took part in the Emperor's campaign in Britain . Under Caracalla he was first governor of the province of Dalmatia , then proconsul of the province of Asia .

Rise to power

On April 8, 217, Caracalla was murdered by conspirators for personal reasons. His successor was his Praetorian prefect Macrinus , who was involved in the murder plot . The Severan dynasty was thus disempowered. Soon afterwards Julia Domna committed suicide. In 217/218 Avitus also died of old age. Macrinus, who was in Syria, distrusted the relatives of his predecessor. On his orders, Maesa had to withdraw from Rome to her Syrian homeland. She was allowed to keep all her possessions.

With the childless Caracalla, the descendants of Septimius Severus were extinct, but the soldiers of the old dynasty mourned, and Macrinus was unpopular. This situation offered Maesa a chance to secure the dignity of her own offspring, although she was not related by blood to the founder of the dynasty, Septimius Severus, but only by marriage. It helped her that she had a large fortune. Those around them began to agitate against Macrinus. The fourteen-year-old son of their older daughter Julia Soaemias, Varius Avitus (Elagabal), was passed off as the illegitimate son of Caracalla; his real father, the husband of Julia Soaemias, had died in 217. With this appeal to loyalty to the Severer dynasty and with the prospect of generous monetary gifts from Maesa's fortune, the soldiers of Legio III Gallica stationed near Emesa were persuaded to mutiny. According to the account of the contemporary historian Cassius Dio , Maesa did not determine the point in time at which the uprising against Macrinus began, but was surprised by it. Herodian , who was also a contemporary, offers a different description ; According to his report, Maesa was always in control. The rebellion spread rapidly. In Rome, Maesa and her daughters and grandchildren were declared enemies of the state by the Senate.

On June 8, 218, a decisive battle broke out near Antioch , which was chaotic, as both armies lacked competent leadership. Julia Maesa and Julia Soaemias were present on the battlefield. Cassius Dio reports that Macrinus' troops initially had the upper hand, but Maesa and Soaemias were able to persuade the already fleeing soldiers of Elagabal to hold out and thus enable victory. Macrinus tried to escape but was captured and killed.

Role in Elagabal's reign

Capitoline Museums , Rome

| Julius Bassianus |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Julius Avitus Alexianus |

Julia Maesa |

Julia Domna |

Septimius Severus 193-211 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Julia Soaemias |

Julia Mamaea |

Geta 211 |

Caracalla 211-217 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Elagabal 218-222 |

Severus Alexander 222-235 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It was not until the summer of 219 that the new emperor Elagabal arrived in Rome with his mother and grandmother. Because of his youth and because he was more interested in religion than politics and administration, Maesa was primarily responsible for government affairs. Although she was never empress herself, only grandmother of the emperor, Maesa received the title Augusta , which was an extraordinary honor. Julia Soaemias was Augusta too , but she was probably rather apolitical and not as ambitious as Julia Maesa, who was clearly superior to her in terms of rank. Maesa couldn't prevent the very headstrong Elagabal from making himself hated with his oriental customs and careless religious policy.

The dynasty had no support of its own in Rome, where Caracalla's death was celebrated in the Senate, and was completely dependent on the benevolence of the soldiers and Praetorians stationed there . Their loyalty was essential for survival; a violent overthrow of the dynasty would have been life-threatening for all members of the imperial family, because it had to be expected that a new ruler would kill all members of his predecessor. Hence Maesa was concerned about the soldiers' displeasure; she recognized the danger to her rule in this. In vain had she recommended to Elagabal from the beginning restraint and consideration for the expectations of the Romans. Now she is said to have even hated him.

As the situation was heading for disaster, Maesa decided to sacrifice her ruling grandson. She began to build up together with her younger daughter Julia Mamaea, her teenage son Severus Alexander as the successor of Elagabal. He was also passed off as the illegitimate son of Caracalla. Elagabal had to adopt him and make him Caesar . When the emperor realized that this was to initiate his disempowerment, he sought the life of his cousin Severus Alexander. The rivalry between the two cousins and their mothers developed into a life-and-death struggle in which Maesa stood on the side of her younger daughter and played a decisive role. The soldiers resolutely rejected Elagabal and were won over to Severus Alexander with donations of money. On March 11, 222 Julia Soaemias and Elagabal were murdered by mutinous soldiers. Severus Alexander could easily take power and gain recognition as emperor. It testifies to Maesa's tactical skill that this delicate change of power went smoothly, even though the new emperor was only thirteen years old, the Syrian influence in Rome was unpopular after the experience with Elagabal and the soldiers could easily proclaim a person of their own choice as emperor can.

Role in the reign of Severus Alexander

In contrast to Elagabal, Severus Alexander turned out to be steerable. He was completely devoted to his power-conscious and assertive mother. It is unclear whether Maesa and Mamaea worked together harmoniously or whether there was - as some researchers suspect - a Maesa party and a Mamaea opposing party and a power struggle between them. Maesa was already old then. She died probably around 224/225.

reception

Antiquity

After her death, Maesa was elevated to a deity as part of the Roman imperial cult . To commemorate her consecration , coins were minted on which she is referred to as Diva Maesa Augusta , i.e. as divine. It is also attested to be deified in inscriptions. The erasure of her name on an inscription must have occurred under the emperor Maximinus Thrax (235-238), who imposed the damnatio memoriae on her grandson Severus Alexander . It is unclear to what extent this measure also extended to Alexander's relatives.

The contemporary historians Cassius Dio and Herodian as well as the Late Antique Historia Augusta provide information about Maesa . Despite Maesa's responsibility for Elagabal's seizure of power, which all historians report with disgust, it is not condemned in the sources, but portrayed partly neutrally and partly with respect. Cassius Dio downplays Maesa's role in the uprising of Elagabal. One reason for this may be the fact that he wrote during the reign of Severus Alexander and did not want to hold the grandmother of the reigning emperor responsible for Elagabal's rise to power. Herodian emphasizes Maesa's strong ambition. The author of the Historia Augusta largely follows the account of Herodian, to which he also refers repeatedly. His portrayal is shaped by his fundamental rejection of female rule.

Modern

In research, Maesa was previously considered to be one of the key figures of a fateful "orientalization" at the time of the late Severians. However, historians such as Alfred von Domaszewski , Karl Bihlmeyer and Franz Altheim , who were very critical of the Syrian influence in the late Severan period, were also impressed by Maesa's political skill and assertiveness. Von Domaszewski (1909) described her as a “bold and clever woman”. Bihlmeyer (1916) considered her “ingeniously executed putsch” against Macrinus to be a step with which she “dared the unbelievable” and brought about it, because she was a “master of human treatment and intrigue”. Altheim (1952) judged that Maesa's "essence [...] is not very far from size". In recent research, too, her will for power and daring are emphasized. Matthäus Heil characterizes them as unscrupulous and determined to take any risk.

The hypothesis of an orientalization brought about by Syrian women is mostly viewed with skepticism in recent research. Erich Kettenhofen points to the continuity of the development of the imperial term ruler. He stated that a “break-in of oriental concepts of rule and cult forms” under the influence of Syrian women was “difficult to prove”. Karl Christ, on the other hand, believes that the “despotic” Maesa ensured that “the world of her homeland, the world of Emesa” found its way into Rome and had an impact on world history there. She was "the driving force in this political process". Christ also emphasizes, however, that the women of the Severan house were wrongly demonized as "power-hungry and greedy oriental natures". The catastrophes "did not occur as a result of an inadequate commitment of women, but because of the unsuitability of the male members of the dynasty".

Kettenhofen points out that the source base of the common idea of a decisive role for Maesa during the reign of Elagabal is narrow. He opposes an overestimation of their influence. Robert Lee Cleve takes a different view. He sees in Maesa an extraordinarily capable regent who discreetly steered the empire from the background.

literature

- Erich Kettenhofen : The Syrian Augustae in the historical tradition. A contribution to the problem of orientalization . Habelt, Bonn 1979, ISBN 3-7749-1466-4 .

- Helmut Halfmann : Two Syrian relatives of the Severan imperial family . In: Chiron 12, 1982, pp. 217-235.

- Bruno Bleckmann : The Severan family and the soldier emperors . In: Hildegard Temporini-Countess Vitzthum (Hrsg.): Die Kaiserinnen Roms . Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-49513-3 , pp. 265–339, here: 279–293 (overview with few references).

iconography

- Max Wegner : Iulia Maesa . In: Heinz Bernhard Wiggers , Max Wegner: Caracalla, Geta, Plautilla. Macrinus to Balbinus (= The Roman Emperor , Section 3 Volume 1). Gebrüder Mann, Berlin 1971, ISBN 3-7861-2147-8 , pp. 153-160.

Web links

- Herbert W. Benario: Short biography (English) at De Imperatoribus Romanis (with references).

- Jona Lendering: Julia Maesa . In: Livius.org (English)

Remarks

- ↑ Herodian 5,3,2 and 5,8,3; Cassius Dio 79 (78), 30.3. When specifying some of the books of Cassius Dio's historical work, different counts are used; a different book count is given here and below in brackets.

- ↑ On the career of Avitus see Helmut Halfmann: Zwei Syrische Relatives des Severischen Kaiserhaus . In: Chiron 12, 1982, pp. 217-235, here: 219-225; Markus Handy: Die Severer und das Heer , Berlin 2009, pp. 50–56; Hans-Georg Pflaum : La carrière de C. Iulius Avitus Alexianus, grand'père de deux empereurs . In: Revue des Études latines 57, 1979, pp. 298-314.

- ↑ For the dating see Helmut Halfmann: Two Syrian relatives of the Severan imperial family . In: Chiron 12, 1982, pp. 217-235, here: 223.

- ↑ Herodian 5: 3, 2–3.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 79 (78), 31.

- ↑ Herodian 5: 3, 9-12.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 79 (78), 38.1.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 79 (78), 38.4.

- ↑ Erich Kettenhofen: The Syrian Augustae in the historical tradition , Bonn 1979, p. 145.

- ↑ Herodian 5,7,1.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 80 (79), 15.4; Herodian 5,5,5-6.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 80 (79), 19.4.

- ↑ See also Robert Lee Cleve: Severus Alexander and the Severan Women , Los Angeles 1982, pp. 106-113.

- ↑ Herodian 5,8,1-3.

- ↑ For the hypothesis of a rivalry, Erich Kettenhofen pleads: Die syrischen Augustae in der historical tradition , Bonn 1979, p. 45. Cf. Fulvio Grosso: Il papiro Oxy. 2565 e gli avvenimenti del 222-224 . In: Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei , row 8: Rendiconti. Classe di Scienze morali, storiche e filologiche , Vol. 23, 1968, pp. 205-220, here: 207-211. Robert Lee Cleve: Severus Alexander and the Severan Women , Los Angeles 1982, pp. 183, 241-242 and Elizabeth Kosmetikatou: The Public Image of Julia Mamaea, disagree . In: Latomus 61, 2002, pp. 398-414, here: 400; they assume that the two women are on good terms.

- ↑ For the dating see Erich Kettenhofen: On the date of death Julia Maesas . In: Historia 30, 1981, pp. 244-249; James Frank Gilliam : On Divi under the Severi. In: Jacqueline Bibauw (ed.): Hommages à Marcel Renard , Vol 2, Brussels 1969, p 284-289, in this case. 285 AD.

- ↑ Herodian 6,1,4.

- ^ The Roman Imperial Coinage , Vol. 4 Part 2, London 1938, p. 127 (No. 712-714).

- ↑ Arthur Stein , Leiva Petersen (ed.): Prosopographia Imperii Romani , 2nd edition, part 4, Berlin 1952–1966, p. 321 (I 678).

- ↑ CIL VIII, 2564 .

- ^ Elisabeth Wallinger: The women in the Historia Augusta , Vienna 1990, p. 95.

- ↑ Herodian 5: 3, 11.

- ^ Elisabeth Wallinger: The women in the Historia Augusta , Vienna 1990, pp. 93–97.

- ^ Alfred von Domaszewski: History of the Roman Emperors , Vol. 2, Leipzig 1909, p. 272.

- ↑ Karl Bihlmeyer: The "Syrian" Emperors in Rome (211–35) and Christianity , Rottenburg 1916, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Franz Altheim: Niedergang der alten Welt , Vol. 2, Frankfurt am Main 1952, p. 273.

- ↑ Matthäus Heil: Elagabal . In: Manfred Clauss (Ed.): The Roman Emperors. 55 historical portraits from Caesar to Justinian , 4th edition, Munich 2010, pp. 192–195, here: 193.

- ↑ Erich Kettenhofen: The Syrian Augustae in the historical tradition , Bonn 1979, p. 176.

- ↑ Karl Christ: History of the Roman Empire , 6th edition, Munich 2009, pp. 626, 633–634.

- ↑ Erich Kettenhofen: The Syrian Augustae in the historical tradition , Bonn 1979, pp. 33–42.

- ^ Robert Lee Cleve: Severus Alexander and the Severan Women , Los Angeles 1982, pp. 100-102, 105, 128-131, 141.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Julia Maesa |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Sister of Julia Domna, grandmother of Elagabal and Severus Alexander |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 2nd century |

| DATE OF DEATH | at 224 |

| Place of death | Rome |