Jakarta Charter

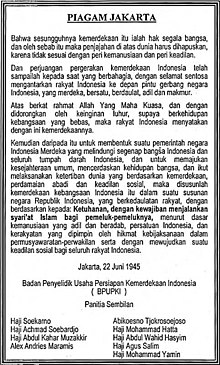

The Jakarta Charter ( Indonesian Piagam Jakarta ) is a draft for the preamble to the Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia , which was approved on June 22, 1945 by a special commission of the “Committee of Inquiry into the Preparation of Indonesia's Independence” ( Badan Penyelidikan Usaha-Usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan ; BPUPK) in Jakarta was submitted.

The document contains the five principles of the Pancasila ideology, but also a clause that obliges Muslims to observe the Sharia . This addition, which is also known as the "Seven Words" (tujuh kata) , was deleted from the constitution by the commission that finally enacted and enacted the constitution after the Indonesian declaration of independence on August 18, 1945. During the 1950s, when the 1945 constitution was suspended, representatives of the Islamic parties in Indonesia repeatedly called for a return to the Jakarta Charter. They stressed that it was the result of a political compromise between nationalist and Islamic delegates in the first constitutional body. In order to accommodate the representatives of the Islamic camp, President Sukarno announced in his decree of July 5, 1959, with which he reinstated the constitution of 1945, that the Jakarta Charter “filled the constitution with life” and formed “an association” with it . The meaning of this statement was much debated in the following years: While the secularists saw it only as a recognition of the Jakarta Charter as a “historical document”, the Islamic groups believed that this decree made the Jakarta Charter with its “seven words “Got legal significance, and on this basis pushed forward the introduction of an Islamic legal system with its own laws for Muslims. The Jakarta Charter was again the subject of political debate during the constitutional reforms at the beginning of the Reformasi era (1999–2002) because various Islamic parties demanded the inclusion of the “Seven Words” in Article 29 of the Constitution, which deals with the position the religion in the state and religious freedom . However, the amendments tabled by the Islamic parties did not receive the necessary majority. The Front Pembela Islam ("Front of the Islam Defenders") fights to this day for the restoration of the Jakarta Charter.

The Jakarta Charter in the 1945 constitutional process

Background: The BPUPK Committee and the Neuner Commission

In 1942, Japan occupied the territory of the Dutch East Indies and replaced the Dutch as colonial power. From the beginning of the occupation, the Japanese military government relied on the cooperation of the existing nationalist leaders in order to keep the costs of the occupation and warfare as low as possible. In order to make this cooperation with the nationalists in Java as effective as possible, the Japanese military government organized the Djawa Hōkōkai mass movement in early January 1944, which replaced the dissolved Pusat Tenaga Rakyat (PUTERA). In connection with the looming Japanese defeat in the Pacific War , the Japanese Prime Minister Koiso Kuniaki announced in September 1944 the "future independence of the entire Indonesian people".

With reference to this, the Japanese military authority in Java set up the "Committee of Inquiry for Preparation of Independence" (Indonesian Badan Penyelidikan Usaha-Usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan , BPUPK; Japanese Dokuritsu Junbi Chōsa-kai ) in early March 1945 . This committee, which was supposed to lay the foundations for Indonesia's national identity by drawing up a draft constitution, consisted of 62 Indonesian members, 47 of whom belonged to the nationalist and 15 to the Islamic camp. The representatives of the Islamic camp believed that the constitution of the new state should be based on Sharia law. From May 29 to June 2, 1945, the BPUPK met in Jakarta for a first conference. At this conference on June 1 , Sukarno gave his famous speech in which he introduced the principles of pancasila.

Before they split up, the delegates of the BPUPK set up an eight-member Small Commission (Panitia Kecil) , which was headed by Sukarno and had the task of collecting and discussing the proposals submitted by the other delegates. In order to resolve the tensions between the secular nationalists and the representatives of the Islamic camp in this body, Sukarno formed a nine-member special commission on June 18. It was supposed to work out a compromise for the preamble to the future constitution that would satisfy the representatives of both camps. In this commission of nine (Panitia Sembilan) , which was headed by Sukarno, four members represented the Islamic camp and five the secular nationalist camp. The members of the Neuner Commission were:

| Name (life data) | Alignment | grouping | image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agus Salim (1884–1954) | Islam nationalist | Sarekat Islam |

|

| Abikoesno Tjokrosoejoso (1897–1968) | Islam nationalist | Partai Serikat Islam Indonesia (PSII) |

|

| Wahid Hasjim (1914-1953) | Islam nationalist | Nahdlatul Ulama |

|

| Abdoel Kahar Moezakir (1907–1973) | Islam nationalist | Muhammadiyah |

|

| Sukarno (1901-1970) | Secular nationalist | Partai Nasional Indonesia, Pusat Tenaga Rakyat |

|

| Mohammad Hatta (1902–1980) | Secular nationalist | Partai Nasional Indonesia, Pusat Tenaga Rakyat |

|

| Achmad Soebardjo (1896–1978) | Secular nationalist |

|

|

| Mohammad Yamin (1903–1962) | Secular nationalist | Pusat Tenaga Rakyat |

|

| Alexander Andries Maramis (1897–1977) | Secular nationalist, representative of Christians | Perhimpunan Indonesia |

|

On June 22, 1945, this commission presented the following text as a proposal for the preamble to the constitution, later referred to by Mohammad Yamin as the "Jakarta Charter" (Piagam Djakarta) .

Text and translation of the Jakarta Charter

" Text in old spelling

Bahwa sesoenggoehnja kemerdekaan itoe jalah hak segala bangsa, dan oleh sebab itoe maka pendjadjahan diatas doenia haroes dihapoeskan, karena tidak sesoeai dengan peri-kemanoesiaan dan peri-keadilan."

German translation

Since independence is truly the right of every people, colonialism must be removed from the earth because it is not in harmony with humanity and justice.

"Dan perdjoeangan pergerakan kemerdekaan Indonesia telah sampailah kepada saat jang berbahagia dengan selamat-sentaoesa mengantarkan rakjat Indonesia kedepan pintoe gerbang Negara Indonesia jang merdeka, bersatoe, berdaoelat, adil dan makmoer."

"The struggle of the movement for Indonesia's independence has now surely come to the happy moment when the Indonesian people stand safe and sound at the gates of an Indonesian state that is independent, united, sovereign, just and prosperous."

"Atas berkat Rahmat Allah Jang Maha Koeasa, dan dengan didorongkan oleh keinginan luhur, soepaja berkehidupan kebangsaan jang bebas, maka rakjat Indonesia dengan ini menjatakan kemerdekaanja."

"With the blessing and grace of God Almighty and driven by the sincere wish that national life may develop freely, the Indonesian people hereby declare their independence."

"Kemoedian dari pada itu untuk membentoek soeatu Pemerintah Negara Indonesia jang melindeni segenap bangsa Indonesia dan seloeroeh toempah-dara Indonesia, dan oentoek memadjoekan kesedjahteraan oemoem, mentjerdaskan kehidoepan bangadide, kehidoepan kangosande kehidoepan bangadide, kehidoepan a ka da ka, kehidoepan, ka, ka, ka, ka, ka, ka, ka, ka, ka, and kaşa, dan ikoet kemerdekaan kebangsaan Indonesia itoe dalam soeatu hoekoem dasar Negara Indonesia jang terbentuk dalam soeatu soesoenan negara Republic of Indonesia, jang berkedaoelatan rakjat, dengan berdasar kepada: ke-Toehanan, dengan kewano'etn Islam, kewad'an Islam, peroemilekaresia, pajemari'etan Islam, peroemeloatekar-bag , persatoean Indonesia, dan kerakjatan jang dipimpin oleh hikmat kebidjaksanaan dalam permoesjawaratan / perwakilan serta dengan mewoedjoedkan soeatu keadilan sosial bagi seloeroeh rakjat Indonesia. "

“After that, to form a government of the State of Indonesia that protects the entire Indonesian people and the entire Indonesian homeland, and to promote public welfare, develop the lives of the people and help shape a world order based on freedom, lasting peace and social justice, the national independence of Indonesia is set out in a constitution of the state of Indonesia, which is shaped in the form of a republic of Indonesia, which makes the people the sovereign bearer of state power and to divine rule, with the obligation to exercise the Sharia of the Islam for whose followers, according to just and civilized humanity, the unity of Indonesia, and democracy, guided by the wise policy of advice and representation, is founded and creates social justice for the entire Indonesian people. "

The document is dated June 22, 2605 on the Japanese Koki calendar , which corresponds to June 22, 1945, and is signed by the nine members of the special commission.

The Jakarta Charter as a compromise

In its fourth and last paragraph, the Jakarta Charter contains the five principles of the Pancasila, which, however, are not explicitly designated as such:

- divine rule, with the obligation to observe the Islamic Sharia for its followers,

- just and civilized humanity,

- Unity of Indonesia,

- Democracy, guided by the wise policy of advice and representation,

- social justice for the whole Indonesian people.

This version of the pancasila is also known as the "June 22nd Pancasila Formula". In contrast to Sukarno's speech of June 1, 1945, in which the Pancasila doctrine was formulated for the first time, the fifth principle of ke-Toehanan in the Jakarta Charter - to be translated as "divine rule" or "belief in God" - was in set the first place.

The most important difference in the document, however, was the addition to the first principle of the ke-Toehanan "with the obligation to observe the Islamic Sharia for its followers" (dengan kewadjiban mendjalankan sjari'at Islam bagi pemeloek-pemeloeknja) . This formula, known in Indonesia as the “Seven Words”, recognized the status of Sharia law for Muslims, but remained deliberately ambiguous as to who is obliged to use it, the state or the individual. With this compromise, the different political ideas of the BPUPK members should be balanced.

The implementation of the compromise in the BPUPK

After the deliberations of the Neuner -ommission, the BPUPK met from July 10th to 17th, 1945 under the leadership of Sukarno for its second meeting to preliminarily discuss the main problems in connection with the constitution, including the draft preamble to the Jakarta Charter . Sukarno announced the Jakarta Charter on the first day with his report on the discussions on the Constitution that had taken place since the first meeting and reported that the Small Commission had unanimously adopted it. The core of their ideas, he suggested, came from the members of the BPUPK.

On the second day of the meeting, July 11th, three members objected to the document. The first was Johannes Latuharhary, a Protestant representative from Ambon , who argued that the seven-word formula would force the Minangkabau to change their Adat law and create difficulties with traditional land and inheritance law in the Moluccas . The other two were Wongsonegoro (1887–1978), a liberal Javanese, and the lawyer Hoesein Djajadiningrat (1886–1960). They objected to the seven words on the grounds that they would lead to fanaticism because they created the impression that Muslims were forced to obey Sharia law. Wahid Hasjim, one of the members of the Nine Commission, argued against it that some of the seven words might go too far, but conversely there are other BPUPK members of the Islamic camp for whom this formula does not go far enough.

In order to accommodate this, Wahid Hasjim proposed on July 13th that Article 29 of the constitution, which deals with religion, also includes the provision that the president must be a Muslim and the state religion is Islam, with an additional clause that Guaranteed freedom of religion to non-Muslims . He justified this with the fact that religion alone provided legitimation for the use of force and that the matter was therefore important for national defense. Another BPUPK delegate, Oto Iskandar di Nata, spoke out against the requirement that the President be a follower of Islam and suggested that the seven words of the Jakarta Charter in the article on religion (Article 29) be included to repeat.

The draft preamble to the Jakarta Charter was discussed again at a meeting on July 14th, partly because it should also be used for the declaration of independence. At this meeting, the Muhammadiyah leader Ki Bagoe's Hadikoesoemo demanded that the restriction bagi pemeloek-pemeloeknja ("for their followers") should be deleted from the formula of the seven words . He saw the limitation of the obligation to the Muslims as an insult to his religious group. Sukarno, however, defended the seven-word clause as a compromise necessary to win non-Muslim consent. After portraying Muhammad Yamin, he said on that occasion:

“In short, this is the best compromise. That is why the Commission stuck to the compromise which the honored member Muhammad Yamin called 'Jakarta Charter' and which the honorable member Soekiman advocated as a 'gentleman agreement', so that it would be respected between the Islamic camp and the nationalist camp. "

Soekiman Wirjosandjojo (1898–1974) was an Indonesian politician of the Masyumi party. Hadikusumo only gave in after the intervention of another politician from the Islamic camp.

However, on the evening of July 15, when the new draft of Article 29 of the Constitution was discussed, which now also contained the seven words, Hadikusumo put forward his request again. As little attention was paid to this demand, he announced that he did not agree with the compromise of the Jakarta formula. As this and other difficulties stalled the negotiations, Sukarno opened the session on the last day (July 16) with a request to the nationalist group to agree to a great sacrifice, namely to allow that, in addition to the seven words of the Jakarta Charter also the article is included that the President of the Republic of Indonesia must be an Indonesian Muslim. As the nationalist group complied with this request, the BPUPK passed a draft constitution that not only contained the seven words that required Muslims to comply with Sharia law in two places - in the preamble and in Art. 29, but also the provision that the president had to be a Muslim.

The rejection of the seven words after the declaration of independence

The rapid political developments following the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (August 6th and 9th) and the speech by Emperor Hirohito to end the war (August 15th) created a situation in which all the concessions that were made during the second conference the BPUPK had made the Islamic groups were reversed. On August 14 or 15, 1945, the Japanese set up a new commission, the Commission for the Preparation of Indonesian Independence ( Panitia Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia - PPKI). It included only four of the nine signatories of the Jakarta Charter, namely Sukarno, Mohammad Hatta, Achmad Soebardjo and Wahid Hasjim.

This body met on August 18, 1945, one day after Indonesia's declaration of independence , to vote on the state constitution. In the morning, Mohammad Hatta held a preliminary talk with the delegates who were present, in which he proposed that the seven controversial words in both the preamble and Article 29 be deleted. As Hatta later reported in his book “All about the proclamation of August 17, 1945” (Sekitar Proklamasi 17 Agustus 1945) , a Japanese naval officer had come to him the previous evening and informed him that Christian nationalists from the eastern regions Indonesia's rejected the seven-word clause of the Jakarta Charter as religious discrimination and, if retained, preferred to stand outside the Republic of Indonesia. In the draft that Hatta submitted to the committee, various other formulations were also changed in order to establish religious neutrality. So the expression ke-Toehanan ("Divine Rulership ", "Belief in God") was replaced by ke-Toehanan Jang Maha Esa (" Rulership of God the All-One", "Belief in God the All-One"), and as The title for the preamble was not the Arabic term “Mukadimah”, but the Indonesian word “Pembukaan”. The PPKI unanimously adopted the constitution in this form on August 18, 1945. So the constitution was passed without the addition of the seven words.

The reason why the PPKI panel accepted the amendment to the draft constitution without resistance was much puzzled later. Among other things, it is stated that this body had a completely different composition than the BPUPK. Only 12 percent belonged to the Islamic camp (compared to 24 percent in the BPUPK). Of the nine signatories to the original Jakarta Charter, only three were present that day. However, none of them belonged to the Islamic camp; Wahid Hasjim, who was arriving from Surabaya , did not arrive in Jakarta until one day later, on August 19th. It is also pointed out that at that time the country was surrounded by Allied troops, was in a dangerous situation and the defense of its newly gained independence was a top priority.

However, the representatives of political Islam did not agree with the amendment to the draft constitution. Their disappointment was heightened by the fact that on August 19 the PPKI committee rejected the creation of its own ministry of religion. In November 1945, based on the Islamic representative body founded under the Japanese occupation, they founded the Masjumi party , which demanded the reinstatement of the Jakarta Charter. Only the appearance of Dutch troops trying to occupy the country again forced them to cooperate with the republican government.

Discussions about the Jakarta Charter after the 1945 constitution was repealed

Demands of the Islamic parties for recognition of the Jakarta Charter

On December 27, 1949, the 1945 constitution was replaced by a new constitution, the United States Constitution of Indonesia . This was in turn replaced on August 17, 1950 by the Provisional Constitution of Indonesia . Even in the debates that preceded the adoption of the Provisional Constitution of 1950, the Masyumi party repeatedly called for institutional recognition of the Jakarta Charter. Abikoesno Tjokrosoejoso, a member of the Neuner Commission, published a pamphlet in 1953 entitled "The Islamic Ummah of Indonesia Before the General Elections," on the front page of which the Jakarta Charter was printed as the ideal to be pursued.

The Jakarta Charter was also an important topic in the Constituent Assembly , the constituent assembly that was elected in December 1955 to draft a permanent constitution for Indonesia. In total, the body consisted of 514 MPs, of which 230, or 44.8 percent, belonged to the so-called Islamic bloc, while most of the other MPs belonged to parties with a secular orientation. The Islamic bloc, to which a total of eight parties belonged (Nahdlatul Ulama, Masyumi, PSII, Perti and four smaller groups), united the view that the deletion of the seven words of the Jakarta Charter was a wrong and fateful decision by the Muslim group in the PPKI only because of the emergency of the time and because of Sukarno's promise that an elected people's assembly would take up the problem again in the future. Abdoel Kahar Moezakir, a member of the Nine Commission who had joined the Masyumi party, described the deletion of the seven words as a "betrayal" which destroyed the Pancasila itself because, he said, the principles, who had produced the morality of the pancasila included in the Jakarta Charter, the form of the pancasila had lost. During the work of the Constituent Assembly in the following years, the Masyumi party, with 112 members the largest Islamic party within the body, repeatedly demanded the institutional recognition of the Jakarta Charter.

Government commitments in spring 1959

Since the members of the Constituent Assembly could not agree on a new constitution, the military, represented by General Abdul Haris Nasution , voted on February 13, 1959, to return to the first constitution of 1945. Sukarno supported this proposal because he hoped to be able to implement his idea of guided democracy better in this way. On February 19, his cabinet unanimously passed a resolution “on the realization of managed democracy within the framework of a return to the 1945 constitution”. In the 24 points of this resolution, the opinion was expressed that the constitution of 1945 offered a better guarantee for the implementation of guided democracy. Item 9 read: "In order to come closer to the desire of the Islamic groups, in connection with the restoration and maintenance of public security, the existence of the Jakarta Charter of June 22, 1945 is recognized." In the "Declaration" it was added that "the purpose the return to the 1945 Constitution is the restoration of the entire national potential, including the Islamic groups, in order to concentrate on the restoration of public security and development in all fields ”. The mention of the Jakarta Charter was intended as a friendly gesture towards the leaders of the Darul Islam movement in West Java , South Sulawesi and Aceh, as well as towards other Islamic politicians in Parliament and the Constituent Assembly, who were familiar with the ideology of Darul Islam. Movement sympathized. The return to the Constitution of 1945 should be achieved in such a way that the President, at a session of the Constituent Assembly, should urge it to accept this Constitution as the final constitution of Indonesia, with special arrangements being made regarding the existence of the Jakarta Charter .

On March 3 and 4, 1959, Parliament was given the opportunity to ask questions about this Cabinet resolution, which the government would answer in writing. A number of representatives of the Islamic parties asked for clarification about the sentence on the Jakarta Charter. Anwar Harjono of the Masyumi party asked whether this meant that the Jakarta Charter as a document would have the same legal force as the constitution, or only the existence of this historical document should be recognized, to put it “occasionally in the context of public To use security ”. Prime Minister Djuanda Kartawidjaja replied that although the Jakarta Charter was not part of the 1945 constitution, it was still a historical document that had considerable significance for the Indonesian people's struggle for freedom and for the drafting of the preamble to the constitution. Achmad Sjaichu of the Nahdhlatul Ulama wanted to know whether the recognition of the Jakarta Charter should become law, so that the expression "Faith in God" (ketuhanan) in the preamble of 1945 would be supplemented by the famous seven words. And he asked whether it would be possible on this basis to create legislation that is in accordance with Islamic law? Djuanda replied that recognizing the existence of the Jakarta Charter as a historical document for the government also recognized its influence on the 1945 constitution. This influence extends not only to the preamble, but also to Article 29 on religion and religious freedom , which must be the basis for further legislation in the religious field.

President Sukarno delivered a long speech to the Constituent Assembly in Bandung on April 22, 1959, in which he again called for a return to the 1945 constitution and, regarding the Jakarta Charter, stated that it was the message of the suffering of the people (amanat penderitaan rakyat) who gave her life. The Jakarta Charter encompassed the wishes contained in the message of the suffering of the people, namely a just and prosperous society, the unitarian state and counseling in the one-chamber system . The Jakarta Charter is a historical document that preceded the 1945 constitution and influenced it. For this reason he would later hand over the original text of the Jakarta Charter to this session of the Constituent Assembly. Sukarno announced that if the Constituent Assembly approves the new regulation, it would be declared in a charter, the Bandung Charter, which would include the “recognition of the Jakarta Charter as a historical document”.

Disputes over the Jakarta Charter in the Constituent Assembly

At the following sessions of the Constituent Assembly, the Jakarta Charter was repeatedly put back on the agenda by the Islamic leaders. In particular, Saifuddin Zuhri from Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), who later became Minister for Religious Affairs, attached great importance to the problem of the Jakarta Charter. He called on the government to stipulate that the Jakarta Charter has legal significance for the present and can be used as a source for the implementation of Islamic legislation for Muslims. Conversely, representatives of Christian parties emphasized that for them the Jakarta Charter was only a historical document and the forerunner of the preamble, so that it could not and should not serve as a source of law. Abdoel Kahar Moezakir, one of the nine signatories of the Jakarta Charter, expressed regret that the government had put the Jakarta Charter back on the political agenda only to appease the Islamic community, not to appease them To make the basis of the constitution. Representatives of the Islamic parties Perti and PSII promised to support the return to the 1945 constitution if the Jakarta Charter were made the preamble to the constitution. However, the representatives of the PSII demanded that the seven words of the Jakarta Charter should also be included in Article 29 of the constitution.

The climax of the debate was a speech given by NU leader H. Zainul Arifin on May 12, 1959, in which he argued that it was not the preamble to the constitution but the Jakarta Charter that was the true basis of the Republic of Indonesia because it paved the way for the proclamation of the Republic of Indonesia. Alluding to the verse of light in the Koran , he compared the Jakarta Charter with the light of the lamp, which like a twinkling star forms an eternal source of light for the constitution to illuminate the dark street on which the Indonesian people walk. Therefore, it must also be recognized as the basic norm for the state and its legislation. Other members of the Constituent Assembly of the Communist Party and the Christian Party opposed this view and emphasized in their speeches that the Jakarta Charter was only a draft.

Prime Minister Djuanda Kartawidjaja stated in the Constituent Assembly on May 21 that, while recognizing the existence of the Jakarta Charter does not mean that this historical document is still valid or has the force of law, it does recognize that the Jakarta Charter complies with the 1945 constitution life, in particular the preamble and Article 29, which should form the basis for legal life in the field of religion. In order to bring the government's point of view into a more binding form, he presented a draft for the Bandung Charter announced by Sukarno, which contained this very statement and to which the Jakarta Charter was attached. The small differences between the government's pronouncements in February, April and May 1959 show that it tried to accommodate the Islamic camp more and more: While the cabinet resolution of February only spoke of recognizing the existence of the Jakarta Charter, Sukarno added the phrase "historical document" in his April proposal. The final draft of the Bandung Charter even recognized that the Jakarta Charter had played a crucial role in the creation of the 1945 constitution.

However, this did not go far enough for the representatives of the Islamic parties. On May 26, they tabled a motion in the Constituent Assembly to insert the seven words into the preamble and article 29. When this amendment was voted on in the Constituent Assembly on May 29, it did not receive the necessary two-thirds majority: only 201 of the total of 466 MPs, or 43.1 percent, voted in favor. As a result, the Islamic parties refused to agree to a return to the 1945 constitution.

After the restoration of the 1945 constitution

Sukarno's decree of July 5, 1959 and the 1966 memorandum

Since the work of the Constituent Assembly had come to a standstill, Sukarno dissolved it by a presidential decree on July 5, 1959, and made the 1945 constitution the final constitution of the state. Sukarno's decree also contained a statement regarding the Jakarta Charter. It was one of five considerations in the first part of the decree. In it, the President reiterated his conviction that the Jakarta Charter filled the constitution of 1945 with life (menjiwai) and with it "forms a unified association" (merupakan rangkaian kesatuan) . This statement is believed to have been in part the result of the efforts of NU leader Wahib Wahab, who was appointed minister of religion shortly thereafter. On June 22, 1959, Parliament acclaimed the return to the 1945 constitution.

On June 22, 1963, the anniversary of the Jakarta Charter was celebrated for the first time. General Abdul Haris Nasution , who was Defense Minister at the time, gave a speech in which he speculated that the Jakarta Charter had incorporated much of the "wisdom" (hikma) of Islamic scholars and leaders that had previously been addressed by letters the Secretariat of Djawa Hokokai had turned. To illustrate the close connection between the Constitution and the Jakarta Charter, Sukarno read aloud the Jakarta Charter and the Preamble to the Constitution on July 5, 1963, the fourth anniversary of his decree.

The "Representative Council of the People for Mutual Aid" ( Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Gotong Royong ; DPRGR), a body newly created by Sukarno within the framework of Guided Democracy, passed a memorandum on the sources of Indonesian law on June 9, 1966. July 1966 by a decree of the newly introduced Provisional Consultative People's Assembly ( Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat Sementara ; MPRS) was ratified. This Decree No. XX / 1966 reaffirmed the historic role of the Jakarta Charter in the constitutional process: “The formulation of the preamble of 1945 was indeed based on the spirit of the Jakarta Charter, and the Jakarta Charter was based on it the spirit of Sukarno's speech of June 1, 1945, which is now known as the speech on 'The Birth of Pancasila'. ”At the same time, however, the decree made it clear that the preamble to the 1945 constitution with the pancasila no longer changed by anyone not even by the Consultative People's Assembly, because a change in the constitution is equivalent to the dissolution of the state. So compared to Pancasila, the position of the Jakarta Charter was unclear and weak, but at least it was mentioned in that decree.

Muslim demands for implementation of the Jakarta Charter

The various political camps interpreted the official statements on the Jakarta Charter very differently. While the nationalists and other non-Islamic and anti-Islamic parties emphasized that this statement was only mentioned under the recitals and therefore did not have the same legal force as the decree, the Islamic groups said that this decree included the Jakarta Charter their “seven words” have been given legal meaning and Muslims are encouraged to apply Sharia law. This also means that special Islamic laws can be made for the Muslim residents of Indonesia.

The NU politician Saifuddin Zuhri, who took over the office of minister of religion in 1962, announced in a speech on the anniversary of the Jakarta Charter in 1963 that the Jakarta Charter was the spark of the national revolution, had constitutional status and had a clear influence on all state legislation and have the ideological life of the whole people. On this occasion, he also formulated a new description of the tasks for his ministry, stating that the work of the agency was aimed at "implementing the presidential decree relating to the Jakarta Charter, which inspired the constitution of 1945". On the occasion of the 40th birthday of the Nahdlatul Ulama in January 1966, a parade was held in which people carried banners expressing their desire to return to the Jakarta Charter. In the same month ulama founded their own association in the province of Aceh , with the explicit aim of implementing the Jakarta Charter and introducing Sharia law in the province, referring to Sukarno's decree of 1959.

In contrast, the reformist Muslim politician Mohamad Roem took a more cautious stance. In a commemorative address at the Islamic University of Medan in February 1967, he emphasized that Muslims are obliged to comply with Islamic law anyway, regardless of whether or not the Jakarta Charter is included in the preamble to the constitution and in the decree of President Sukarno. The Jakarta Charter has a permanent meaning, but not in a legal sense, but rather in a spiritual sense. The permanent religious significance of the Jakarta Charter, which is mentioned in Sukarno's decree, is that it reminds Muslim citizens of their responsibility before God to comply with Islamic law. Mohamad Roem was largely alone with this attitude in the Muslim camp. During the MPRS meeting in March 1968, NU members and supporters of the Partai Muslimin Indonesia requested that the Jakarta Charter also be included in the General Guidelines of State Policy (Garis-garis Besar Haluan Negara: GBHN), but they were able to withdraw because of the opposition of the The military, the Christians and the secular nationalists do not enforce this demand.

Christians and Muslims in dispute over the historical significance of the document

After the MPRS meeting in March 1968, the debate about the Jakarta Charter reached a new high point with several polemical writings from Christian and Muslim sides. The Catholic magazine Peraba published a number of articles by the Catholic Party and secular nationalists criticizing the arguments of proponents of the Jakarta Charter. The Catholic Party argued that the Jakarta Charter never had legal force because it was only the draft preamble to the constitution. Citing Sajuti Melik, a member of the PPKI, the party argued that there was little evidence that the BPUPK sub-commission even signed the draft preamble. It was only Mohammad Yamin who then called this draft Jakarta Charter. Since it was just a draft, the PPKI had the right to drop the seven words. With regard to the 1959 decree, the party emphasized that the word "inspired" contained therein meant that the preamble of 1945 emerged from the Jakarta Charter, but not that the "seven words" had to be adopted into the Indonesian legal system. Otherwise, the decree should have said that the Jakarta Charter replaces the preamble to the 1945 constitution. In addition, this statement only reflects Sukarno's personal convictions, which have no legal force.

The editor of the magazine argued that those who demanded recognition of the Jakarta Charter were violating the unity and integrity of the nation, and rejected claims that the Declaration of Independence had anything to do with the Jakarta Charter. Various young politicians who did not want to cooperate with the Japanese colonial authorities had attached great importance to ensuring that independence would not be associated with the Japanese. That is why they refused to use any words from the Jakarta Charter in the declaration, as they viewed them as a product of the BPUPK commission set up by the Japanese.

In return, Muslim politicians tried to show that the Declaration of Independence was very closely linked to and based on the Jakarta Charter. The reformist Muslim leader Hamka (1908–1981) struck a particularly sharp tone. He argued that prior to the Jakarta Charter, the Indonesian independence movement was split into two groups - Islamic and nationalist - that did not respect one another. Only the compromise formulated in the Jakarta Charter brought the two groups together, but after independence it was fraudulently denounced by the nationalists. The Minister of Religion, Mohammad Dachlan, was somewhat more moderate. Speaking in June 1968 to commemorate the anniversary of the Jakarta Charter, he said that the document was a step towards independence that served as the mainspring and source of inspiration for the Indonesian nation in the struggle to defend independence. The content of the Declaration of Independence was in line with what the Jakarta Charter said and marked the end of the movement for Indonesian independence in the 20th century. Sukarno's decree of 1959 and the memorandum of the DPRGR ratified by the MPRS in 1966 had made it clear that the Jakarta Charter was a valid legal source in the country. The Catholic magazine Peraba then published an article by the Catholic youth in which they criticized Dachlan's understanding of office, suggested the dissolution of the Ministry of Religions and warned that in Indonesia Islam had practically become the religion of the state.

The military was divided over the Jakarta Charter. Abdul Haris Nasution , the spokesman for the People's Congress, stated at a seminar in Malang on “The Development of the Islamic Community” in July 1968 that he opposed the idea of establishing an Islamic state, but supported the desire of Muslims to restore the Jakarta Charter . But when in June 1968 an association of Islamic students wanted to publicly celebrate the anniversary of the Jakarta Charter, the military governor of Jakarta refused to give permission. The government urged the officials not to make any statements about the Jakarta Charter and not to attend the ceremony. The next year, the military commander of the Tanjung Pura Division stationed in Pontianak banned the celebration of the Jakarta Charter anniversary, arguing that the ideology of the state was laid down in the preamble to the 1945 constitution.

Projects to implement the Jakarta Charter in practice

From the late 1960s onwards, the attitude of the representatives of political Islam was determined by the fact that they tried to implement the content of the Jakarta Charter through legislation. However, they were initially faced with the task of defining what the obligation to implement the Sharia actually means. Mohammad Saleh Suaidy, a former Masyumi activist, later said in retrospect that in the late 1960s an attempt was made to implement the Jakarta Charter through the following points: (1) Adoption of the Islamic marriage law, which was still in force at the time was discussed in parliament; (2) administration of the zakāt collection and distribution with the prospect of the later introduction of a zakāt law; (3) Standardization of the curriculum of the Islamic schools in the country; (4) improving the efficiency and coordination of Daʿwa activities; (5) and reactivation of the Islamic Science Council (Majelis Ilmiah Islam) as an institution for the development of Islamic norms.

To achieve the second goal, a semi-state agency for the collection and distribution of Zakāt, the Badan Amil Zakat (BAZ) , was set up in Indonesia as early as 1968 . On the Christian side, however, these developments were viewed with great concern. In February 1969 the Catholic Party protested against the new legislative projects with a memorandum. In it, she demanded that the government should choose between an Islamic and a secular state, and warned that the adoption of the new Islamic legislative projects would undermine the pancasila as the ideological basis of the state and replace it with the Jakarta Charter.

In December 1973, an Islamic marriage law was also passed. The explanations for the introduction of the law referred explicitly to the Jakarta Charter and made it clear that the legislature considered it to be part of the constitution based on Sukarno's decree.

Overall, however, the political program of the Orde Baru period, which was entirely geared towards indoctrination of the Pancasila ideology, left little room for discussion of the Jakarta Charter. In 1973 all Islamic parties were forcibly united in a single party, the Partai Persatuan Pembangunan. In the early 1980s, the government forced all political parties to make the Pancasila their only ideological base and, if necessary, to remove Islam from their ideological repertoire.

1988: New discussions on the occasion of the introduction of religious courts

It only came back to new discussions in 1988, when the government presented a bill to introduce religious courts. The Indonesian Democratic Party and the non-Muslim and secular groups accused the government of wanting to implement the Jakarta Charter with this legislative project. The Jesuit theologian Franz Magnis-Suseno warned that the removal of the seven words of the Jakarta Charter from the preamble had the purpose that none of the social groups should impose their specific ideals on the others. At the beginning of July 1989, representatives of the Conference of Indonesian Bishops (KWI) and the Association of Indonesian Churches (PGI) demanded that Muslims should continue to be free to choose between religious and civil courts, because otherwise they would be obliged to comply with Sharia law, which was not conform to the principles of Pancasila and equate to implementation of Sharia law.

Suharto responded to the criticism by stating that the law was only intended to implement the 1945 constitution and the Pancasila idea, and that the project had no relation to the Jakarta Charter. The Muslim leaders reacted in the same way. Mohammad Natsir accused the Christians of consistently dealing with Islamic aspirations with intolerance, from their "forced" deletion of the seven words of the Jakarta Charter to their opposition to the draft Islamic marriage law in 1969 to their renewed opposition the Law Establishing Religious Courts.

The Muslim intellectual Nurcholis Madjid , on the other hand, showed more understanding for the arguments of the Christian groups . He said that the suspicion that the legislative project was an implementation of the Jakarta Charter was caused by the political trauma of the past, but that this project should be viewed as a national process. In a similar way, the army faction within the Indonesian parliament expressed understanding for the fears of the population that the law project was a realization of the Jakarta Charter, because in the past there had actually been multiple efforts to promote the Pancasila ideology through religion replace.

Demands for a return to the Jakarta Charter at the beginning of the Reformasi era (1999–2002)

The advance of the Islamic parties

After Suharto was overthrown and the restrictions on freedom of speech were lifted in 1998, calls were again made for an Islamic state and for a return to the Jakarta Charter. The background to this was that the Consultative People's Assembly (MPR) began discussions on constitutional reform in October 1999. At the annual meeting of the People's Consultative Assembly in 2000, two Islamic parties, namely the United Development Party ( Partai Persatuan Pembangunan - PPP) and the Crescent Star Party ( Partai Bulan Bintang - PBB), successor to the Masyumi, launched a political campaign for the resumption of the state of the “seven words” of the Jakarta Charter into the constitution, solely through an addition to Article 29, which deals with the position of religion in the state. In this way, the Pancasila formula in the preamble to the constitution should remain intact. Article 29 actually reads:

- The state is founded on belief in the One God.

- The state guarantees the freedom of every citizen to profess their religion and to worship according to their religion and beliefs.

The PBB politician MS Kaban justified the position of his group by saying that it was only drawing the consequences of Sukarno's decree of July 5, 1959, which had clarified the inviolable unity of the constitution and the Jakarta Charter. He considered fears that the discussion of the Jakarta Charter could lead to national disintegration to be unfounded.

The first congress of the Indonesian mujahidun in August 2000 also called for the Jakarta Charter to be included in the constitution and for Sharia law to be applied. The campaign received particular support from the Front Pembela Islam (FPI). Habib Rizieq, the chairman and founder of the FPI, published a book titled “Dialogue” in October 2000 in which he argued that the incorporation of the Jakarta Charter into the Constitution corrected a historical error and provided a strong moral basis for the Indonesian state would offer. Rizieq pointed out that Sukarno himself described the Jakarta Charter as the result of very tough negotiations between Islamic and nationalist groups and signed the document without hesitation. He rejected the view that a return to the Jakarta Charter would make Indonesia an Islamic state. Rather, the Jakarta Charter was the middle way between two mutually exclusive wishes, the desire of the Islamic camp to found an Islamic state and the desire of the nationalist camp to found a secular state. The omission of the Jakarta Charter was a betrayal of democracy and an overthrow of the constitution, which left many sides disappointed and sad. Reintroducing the formula into the constitution is a medicine that will restore their stolen rights. In this way a chronic ideological conflict could be resolved.

A spokesman for the PPP argued in 2002 that Indonesia already had laws referring to Islamic Sharia law, such as the 1974 Marriage Law, the Religious Courts Law of 1989, and the laws on pilgrimage services, administration and application of zakāt the Sharia in Aceh of 1999. All these legal developments should be confirmed by the reintroduction of the Jakarta Charter in Article 29 of the Constitution. Under pressure from the FPI, the Hizb ut-Tahrir and the Council of the Indonesian Mujahidun ( Majelis Mujahidin Indonesia ; MMI), three other smaller Islamic parties joined this position in 2002, which are part of the “Fraction of the Sovereignty of the Umma” ( Perserikatan Daulatul Umma ; PDU) were merged. The position of the PDU only differed from the position of the PPP and PBB in that they wanted to add the seven words of the Jakarta Charter to the second paragraph of Article 29. At the final meeting of the People's Consultative Assembly on constitutional reform in 2002, the PBB and the PDU made a formal request to add the seven words to Article 29 of the Constitution.

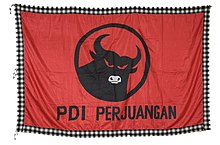

The opponents of the advance

The Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle ( Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan ; PDI-P) opposed the incorporation of the Jakarta Charter into the constitution. The two Islamic mass organizations Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah were now also hostile to this initiative. Ahmad Syafii Ma'arif, the chairman of the Muhammadiyah, said in September 2001 that implementation of the Jakarta Charter would put additional strain on the country, which is on the verge of collapse. A number of other Muslim intellectuals such as Abdurrahman Wahid , Nurcholis Madjid , Masdar F. Mas'udi and Ulil Abshar Abdalla also rejected the plan. The members of Laskar Jihad in Solo were very disappointed that the Muhammadiya did not support the restoration of the Jakarta Charter.

Medina Charter: the alternative proposal of the Reformasi group

In order to bypass the resistance of the secularist parties to the Jakarta Charter, three other moderate Islamic parties, which were united in the so-called Reformasi faction, made an alternative proposal in 2000. It provided for paragraph 1 of Article 29 to be provided with a religion-neutral addition that obliged members of the various religions to comply with their specific religious regulations. They called this planned addition based on the parish rules of Medina as the “Medina Charter” (Piagam Medina), because it was supposed to reflect the religious pluralism of the Prophet Mohammed in his early phase in Medina . The three parties that supported this proposal were the National Mandate Party ( Partai Amanat Rakyat - PAN), the National Awakening Party (PKB) and the Justice Party ( Partai Keadilan - PK), predecessor of the Partai Keadilan Sejahtera (PKS) . The PC stated that it preferred the Medina Charter to the Jakarta Charter for three reasons:

- First, the Jakarta Charter is not final because it is not the only legitimate expression of the implementation of Sharia law in Indonesia;

- Second, it is not compatible with the spirit of Islam because the text of the Jakarta Charter refers only to Muslims, whereas Islam is a mercy for the whole world (raḥma lil-ʿālamīn) ;

- Third, the Medina Charter is much closer to the core of Islam than the Jakarta Charter because it recognizes the legal autonomy of each religion, while the latter privileges certain believers.

Hidayat Nur Wahid, the head of the PK, argued that the Jakarta Charter's role as a compromise between Islamic and secular politicians has outlived itself. Mutammimul Ula, one of the leading figures of the PK, said that his party, as a small party, seeks to avoid negative feelings associated with the Jakarta Charter because of the past. The Medina Charter, like the Jakarta Charter, enforces Islamic law. The alternative proposal was supposed to solve the dilemma that the political atmosphere in Indonesia did not allow the reintroduction of the Jakarta Charter, but on the other hand the PK voters wanted the implementation of Islamic law by changing Article 29.

The failure of plans to amend the Constitution

As early as 1999, the MPR Working Committee had entrusted the preparation of drafts for further constitutional amendments to the First Ad Hoc Committee (Panitia Ad hoc I - PAN I), a 45-member sub-commission in which all eleven MPR parliamentary groups were proportionally represented. The three different drafts for Article 29 (keeping the original text, Jakarta Charter and Medina Charter) were discussed in detail in this body in June 2002. When it became clear that the two proposals for change would not find a majority, Yusuf Muhammad of the PKB proposed a compromise on June 13th, namely that the word kesungguhan (“serious intention”) should include the word kewajiban (“duty”) Could replace the seven-word formula, so that the sentence would result: "with the serious intention of adhering to the Sharia of Islam by its followers". When this compromise also failed to find a majority, he proposed to leave Article 29, Paragraph 1 unchanged and to amend Paragraph 2 as follows: “The state guarantees the freedom of every individual to fulfill their respective religious teachings and duties and to worship according to their faith to celebrate."

After long fruitless discussions in the panel, the three alternatives were given to vote in the annual session of the Consultative Assembly in August 2002. Even if politicians from the PDU and PBB once again emphasized the need to restore the unity of the Jakarta Charter and the Constitution by inserting the seven words in Article 29, this proposal did not meet with sufficient support. Neither of the two constitutional amendment plans was adopted.

Even if the two proposals of the Islamic parties were rejected, it is worth noting that these proposals, which imply the implementation of polycentrism under religious law, enjoyed considerable popularity with many Muslims in Indonesia. According to a survey carried out by the Indonesian daily Kompas in August 2002, the proposal of the Medina Charter, which would have created a system similar to the Ottoman millet system , was supported by 49.2 percent of the respondents, while the proposal to enforce Jakarta Charter was approved by 8.2 percent. If the two figures are taken together, it can be seen that the majority of the population at that time was in favor of the introduction of “religious law polycentrism”. In contrast, only 38.2 percent of those questioned wanted to keep the original text of Article 29.

To this day, the Pembela Islam Front is sticking to the demand for restitution of the Jakarta Charter. Rizieq Syihab justified this at a public FPI event in Bandung in February 2012 with the following words: "With the Pancasila of Sukarno, belief in God is in the ass, while with the Pancasila of the Jakarta Charter it is in the head" (Pancasila Sukarno ketuhanan ada di pantat, sedangkan Pancasila Piagam Jakarta ketuhanan ada di kepala) . Sukmawati Sukarnoputri, Sukarno's daughter, reported this statement to Rizieq Syihab in October 2016 for mocking the pancasila. The process was not yet completed in mid-2018.

literature

- Masykuri Abdillah: Responses of Indonesian Muslim Intellectuals to the Concept of Democracy (1966-1993). Abera, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-931567-18-4 .

- Saifuddin Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945: A History of the Gentleman's Agreement between the Islamic and the Secular Nationalists in Modern Indonesia. McGill University, Montreal 1976 ( digitized version ).

- Saifuddin Anshari: The Jakarta Charter 1945: The Struggle for an Islamic Constitution in Indonesia. ABIM, Kuala Lumpur 1979.

- Endang Saifuddin Anshari: Piagam Jakarta June 22, 1945: Sebuah Consensus Nasional tentang dasar negara Republic of Indonesia (1945–1959). 3rd edition, Gema Insani Press, Jakarta 1997, ISBN 9795614320 .

- BJ Boland: The Struggle of Islam in Modern Indonesia. Slightly changed reprint, Springer, Dordrecht 1982, ISBN 978-94-011-7897-6 , pp. 54-75.

- Simon Butt, Timothy Lindsey: The Constitution of Indonesia: A Contextual Analysis. Hart, Oxford 2012, ISBN 1-84946-018-3 , pp. 226-232.

- RE Elson: Another look at the Jakarta Charter controversy of 1945. In: Indonesia 88 (Oct. 2009) pp. 105-130. Digitized

- RE Elson: Two Failed Attempts to Islamize the Indonesian Constitution. In: Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 28/3 (2013) 379–437. Digitized

- Greg Fealy, Virginia Hooker: Voices of Islam in Southeast Asia. A Contemporary Sourcebook. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, 2006. pp. 209 f.

- Masdar Hilmy: Islamism and democracy in Indonesia: piety and pragmatism. ISEAS, Inst. Of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, 2010. pp. 199-203.

- Nadirsyah pants: Shari'a & constitutional reform in Indonesia. ISEAS, Singapore, 2007. pp. 60-70.

- Nadirsyah Hosen: Religion and the Indonesian Constitution: A Recent Debate. In: Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 36/3 (2005), pp. 419-440.

- Jajang Jahroni: Defending the majesty of Islam: Indonesia's Front Pembela Islam 1998-2003. Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai, 2008. pp. 46-50.

- Norbertus Jegalus: examines the relationship between politics, religion and civil religion using the example of Pancasila. Utz, Munich, 2008. pp. 308-310.

- Rémy Madinier: L'Indonesie, entre démocratie musulmane et Islam intégral: histoire du parti Masjumi (1945–1960). Paris: Éd. Karthala [u. a.] 2012. pp. 75-80.

- Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened: Muslim-Christian Relations in Indonesia's New Order. Amsterdam University Press, Leiden / Amsterdam, 2006. pp. 109–118 ( digitized version ).

- Ridwan Saidi: Status Piagam Jakarta: tinjauan hukum dan sejarah. Majlis Alumni HMI Loyal Untuk Bangsa, Jakarta, 2007.

- Arskal Salim: Challenging the secular state: the Islamization of law in modern Indonesia. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2008. pp. 63-69, 85-92.

- Matti Schindehütte : Civil religion as a responsibility of society - religion as a political factor within the development of the Pancasila of Indonesia. Abera Verlag, Hamburg 2006. P. 125 f.

- Mohammad Yamin : Naskah-persiapan undang-undang dasar 1945. Volume I. Jajasan Prapantja, no place, 1959.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Pants: Shari'a & constitutional reform in Indonesia . 2007, p. 60.

- ↑ Harry Benda: The Crescent and the Rising Sun. Indonesian Islam under the Japanese Occupation, 1942–1945 . The Hague 1958. p. 153.

- ↑ On the grouping (not to be confused with the party of the same name founded in 1946 ), cf. William H. Frederick: The Putera Reports: Problems in Indonesian-Japanese Wartime Cooperation . 2009

- ↑ Chiara Formichi: Islam and the Making of the Nation: Kartosuwiryo and Political Islam in 20th Century Indonesia . 2012 (Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde , Volume 282), p. 75.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 14.

- ↑ Jegalus: The relationship between politics, religion and civil religion . 2009, p. 15 f.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 37.

- ^ Butt / Lindsey: The constitution of Indonesia . 2012, p. 227.

- ↑ Madinier: L'Indonesie, entre démocratie et musulmane Islam intégral . 2012, p. 72.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 63.

- ^ Elson: Another look at the Jakarta Charter controversy of 1945. 2009, p. 112.

- ↑ Fealy / Hooker: Voices of Islam in Southeast Asia. 2006, p. 47.

- ↑ Madinier: L'Indonesie, entre démocratie et musulmane Islam intégral . 2012, p. 76.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 25.

- ↑ There are several slightly different versions of the text of the Jakarta Charter. The text reproduced here follows Schindehütte: Civil religion as a responsibility of society . 2006, p. 229 f.

- ^ Translation largely follows Schindehütte: civil religion as a responsibility of society . 2006, p. 229, but in some places after Boland: The Struggle of Islam in Modern Indonesia . 1982, p. 25 f. corrected.

- ^ Schindehütte: Civil religion as a responsibility of society . 2006, p. 230.

- ↑ Jegalus: The relationship between politics, religion and civil religion . 2009, p. 25.

- ↑ Jegalus: The relationship between politics, religion and civil religion . 2009, p. 257.

- ↑ See Simone Sinn: Religious Pluralism in Becoming: Religious Political Controversies and Theological Perspectives of Christians and Muslims in Indonesia . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, 2014. pp. 134-136.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 27.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 64.

- ^ Schindehütte: Civil religion as a responsibility of society . 2006, p. 125.

- ^ Elson: Another look at the Jakarta Charter controversy of 1945. 2009, p. 114.

- ^ Elson: Another look at the Jakarta Charter controversy of 1945. 2009, p. 115.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 28 f.

- ^ Elson: Another look at the Jakarta Charter controversy of 1945. 2009, p. 115 f.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 29.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 56.

- ↑ Yamin: Naskah-persiapan undang-undang dasar 1945 . 1959, p. 279.

- ^ Elson: Another look at the Jakarta Charter controversy of 1945. 2009, p. 116.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 65 f.

- ↑ Madinier: L'Indonesie, entre démocratie et musulmane Islam intégral . 2012, p. 77.

- ^ Elson: Two Failed Attempts to Islamize the Indonesian Constitution. 2013, p. 379.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 68.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 36.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 46.

- ^ Elson: Another look at the Jakarta Charter controversy of 1945. 2009, p. 120.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 36.

- ^ Elson: Another look at the Jakarta Charter controversy of 1945. 2009, p. 120.

- ↑ Jegalus: The relationship between politics, religion and civil religion . 2009, p. 45.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 41 f.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 65.

- ^ Elson: Another look at the Jakarta Charter controversy of 1945. 2009, p. 122.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 64.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 106.

- ↑ a b Madinier: L'Indonesie, entre démocratie musulmane et Islam intégral . 2012, p. 79.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 82.

- ↑ Madinier: L'Indonesie, entre démocratie et musulmane Islam intégral . 2012, p. 319.

- ^ Elson: Two Failed Attempts to Islamize the Indonesian Constitution. 2013, p. 393.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 79.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 81.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 92.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 93 f.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 83.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 84.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 94.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 84 f.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 86 f.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 96.

- ^ Elson: Two Failed Attempts to Islamize the Indonesian Constitution. 2013, p. 397 f.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 88.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 89.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 89 f.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 98.

- ↑ Jegalus: The relationship between politics, religion and civil religion . 2009, p. 31.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 86.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 130.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 95.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 26.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 113.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 108.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 101.

- ↑ Anshari: The Jakarta Charter of June 1945 . 1976, p. 107.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 130.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 107.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 146.

- ↑ Boland: The Struggle of Islam . 1982, p. 160 f.

- ↑ a b Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 109.

- ↑ a b Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 110.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 112.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 111.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 109 f.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 113.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 131.

- ↑ Abdillah: Responses of Indonesian Muslim Intellectuals . 1997. p. 50.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 114.

- ↑ Jegalus: The relationship between politics, religion and civil religion . 2009, p. 66 f.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 115.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 117.

- ^ Taufik Abdullah: Zakat Collection and Distribution in Indonesia in Mohamed Ariff (Ed.): The Islamic Voluntary Sector in Southeast Asia. Islam and the Econcomic Development of Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore 1991, pp. 50–85, here p. 59.

- ↑ a b c Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 161.

- ↑ Jegalus: The relationship between politics, religion and civil religion . 2009, p. 48.

- ^ Butt / Lindsey: The constitution of Indonesia . 2012, p. 230.

- ^ A b Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 49.

- ↑ a b Abdillah: Responses of Indonesian Muslim Intellectuals . 1997. p. 33.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 196.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 199.

- ↑ a b Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 198.

- ↑ Mujiburrahman: Feeling threatened 2006, p. 202.

- ↑ Jegalus: The relationship between politics, religion and civil religion . 2009, pp. 62, 68.

- ^ Elson: Two Failed Attempts to Islamize the Indonesian Constitution. 2013, p. 404.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 95 f.

- ^ Butt / Lindsey: The constitution of Indonesia . 2012, p. 232.

- ↑ Quoted from Jegalus: The relationship between politics, religion and civil religion . 2009, p. 196.

- ^ Elson: Two Failed Attempts to Islamize the Indonesian Constitution. 2013, p. 411.

- ^ Pants: Religion and the Indonesian Constitution . 2005, p. 425.

- ↑ Fealy / Hooker: Voices of Islam in Southeast Asia. 2006, p. 234.

- ↑ Fealy / Hooker: Voices of Islam in Southeast Asia. 2006, p. 235.

- ↑ Fealy / Hooker: Voices of Islam in Southeast Asia. 2006, p. 236.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 95.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 98.

- ^ Butt / Lindsey: The constitution of Indonesia . 2012, p. 232.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 89.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 93.

- ↑ Pants: Shari'a & constitutional reform in Indonesia . 2007, p. 93 f.

- ↑ Jahroni: Defending the majesty of Islam . 2008, p. 69.

- ^ Pants: Religion and the Indonesian Constitution . 2005, p. 426.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 90.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 99 f.

- ^ Elson: Two Failed Attempts to Islamize the Indonesian Constitution. 2013, p. 413.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 101.

- ^ Pants: Religion and the Indonesian Constitution . 2005, p. 432.

- ^ Elson: Two Failed Attempts to Islamize the Indonesian Constitution. 2013, p. 404.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 102.

- ↑ Negara menjamin kemerdekaan tiap-tiap penduduk untuk memeluk dan melaksanakan ajaran / kewajiban agamanya masing-masing dan untuk beribadah menurut agamanya itu , cit. after Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 103.

- ^ Elson: Two Failed Attempts to Islamize the Indonesian Constitution. 2013, p. 418 f.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 106 f.

- ^ Salim: Challenging the secular state . 2008, p. 174.

- ↑ The video from February 15, 2012 is available on the FPI YouTube channel Habib - Pancasila Soekarno & Pancasila Piagam jakarta (ASLI) .

- ↑ Erna Mardiana: Ini Kronologi Kasus Dugaan Penodaan Pancasila oleh Habib Rizieq Detik News January 30, 2017.

- ↑ Ahmad Toriq: FPI: Kapitra Tak Terlibat SP3 Case Penghinaan Pancasila Habib Rizieq Detiknews July 20, 2018.