Front Pembela Islam

The Front Pembela Islam (“Front of the Islam Defenders, Islamic Defenders Front”), abbreviated FPI , is a militant Islamic mass organization based in Jakarta that fights for the introduction of Sharia law in Indonesia and uses violence against those who it believes Violate Sharia law or attack Islam. In doing so, it is based on the Koranic principle of the domain of what is right and prohibition of what is reprehensible . Other goals of the organization are Daʿwa , Jihad and the establishment of an international caliphate . The FPI has an anti-communist , anti-Zionist and anti-American orientation and also fights against Ahmadiyya and liberal Islam .

The FPI was founded on August 17, 1998 a few months after the resignation of President Suharto and has branches in 28 Indonesian provinces. There is very different information about the number of its members, varying between 100,000 and seven million. Most of the FPI members live in the Jakarta metropolitan area . The spiritual leader of the FPI is the Arab scholar and prophet descendant al-Habib Rizieq bin Hussein Syihab, whose family comes from the Hadramaut . He is venerated by his followers as the “Grand Imam ” (imam besar) . After various criminal charges were brought against him, he fled to Saudi Arabia in May 2017 .

The International Crisis Group ruled in 2008 that the FPI is actually an “ urban thug organization” . Within Indonesian society, however, the opinion on the FPI is divided: Although the majority of the population rejects the FPI because of its militancy and religious intolerance, the organization also has many sympathizers in state institutions ( army , police and judiciary) and works closely with it different Islamic parties together. Because of the FPI's religious justification for its organized violence, the state has difficulty treating its activities as purely criminal activities. One of the fiercest opponents of the FPI was Basuki Tjahaja Purnama , also known as Ahok, governor of Jakarta from November 2014 to May 2017. On May 9, 2017, he was sentenced to two years' imprisonment for blasphemy on the basis of a complaint supported by the FPI . On January 24, 2019, he was released early from prison for good conduct.

Foundation and name

The FPI was founded on the evening of August 17, 1998 in the Pesantren School al-Umm in Kampung Utan, Ciputat. The place is in the south of Jakarta , but today belongs to the province of Banten . A total of 20 Muslim preachers and religious scholars attended the founding meeting, most of whom were relatively young at the time. This included in particular:

- Habib Muhammad Rizieq bin Hussein Syihab, who pioneered the founding of the organization and is now at the head of the organization.

- Habib Idrus Jamalullail, a well-known Jakarta preacher.

- KH Cecep Bustomi. However, he left the organization again in 1999 because he thought it was too indulgent and founded the group Laskar Hisbullah together with other FPI members who were loyal to him.

- KH Misbahul Anam, a preacher who received his religious training from the Nahdlatul Ulama . He was the head of the Pesantren al-Umm where the group met and was also appointed the organization's first general secretary. The first secretariat of the FPI was also located in his Pesantren in Ciputat until it was relocated to Tanah Abang in central Jakarta in 1999. Misbahul Anam is originally from Brebes in northern Central Java, is the Tijaniyyah -Orden on.

- Habib Husein Al-Habsyi, who had bombed the Borobodur in 1985 and then served a long prison sentence.

Further founding members were Habib Idrus Jamalullail, Habib Muhsin Ahmad Alatas, KH Salim Nasir, H. Tubagus Muhammad Shiddik, KH Didin Damanhuri, KH Fahrul Razi Ishak, KH Amin Sarbini, Habib Muhdor al-Muhdor, KH Oemar Syahroeni, Habib Abdurrah , KH Zuhri Yakub and KH Sumarno Syafii. The religious scholars in this list can be recognized by the fact that their names are preceded by the abbreviation KH (= Kiai Haji). Kiai is an Indonesian form of address for venerable Islamic scholars, Haji means Mecca pilgrim .

Initially, the FPI members consisted mainly of the supporters of these founding members. For example, all students of Pesantren al-Umm were called upon to support the FPI. According to Rizieq Syihab, the FPI was founded spontaneously, without a formal process preceding it. However, the formation of the organization was unconsciously initiated by the founding members during the rule of Suharto in the 1990s.

When it was founded, the FPI was suspected of being a political instrument of the recently overthrown Suharto regime. However, Rizieq Syihab rejects this as "infamous propaganda" (propaganda keji) . According to Purnomo, most of the FPI founders had previously fought the Suharto regime. Habib Idrus Jamalullail in particular had sharply criticized the Suharto regime. According to FPI members interviewed by Purnomo, the Orde Baru period was actually an “order of thieves” (Orde Maling) . Rizieq Syihab names two reasons as the background for founding the FPI:

- the long suffering of Muslims in Indonesia caused by the weakness of social control by civil and military authorities, resulting in human rights violations and repression by officials of these authorities.

- the existence of a duty to defend the dignity of Islam and Muslims.

In the statutes of the FPI adopted in 2003, the composition of its name is explained as follows:

- Front means that the organization strives to be in the forefront and take a firm stance at every step of the struggle.

- Pembela ("defender") pointed out that the organization wanted to take an active role in the defense of the rights of Islam and the Islamic ummah .

- Islam expresses that the struggle of the organization is not detached from the commitment to the teaching of the straight and true Islamic Sharia.

Ideological development

Defense of Muslims, defense against the "Christianization" of Indonesia

The idea that the FPI serves as an organization for the defense of Muslims was particularly strong in the early days. Shortly after it was founded, the FPI sent an investigation team to Banyuwangi in East Java to investigate the murders of Islamic clergymen that had occurred there. She came to the conclusion that these murders were mainly committed by people disguised as ninja warriors. Therefore, on October 28, 1998, she declared jihad in a fatwa for this ninja group . One month later, on November 22, 1998, the FPI was involved in a bloody confrontation with a Christian Ambonese militia in Ketapang, central Jakarta. According to the FPI, this dispute began when, after an argument at a gambling hall, several hundred Ambonese attacked the place in the early morning and burned down a mosque. When the news spread in Jakarta, several thousand Muslims came to Ketapang, including 300 FPI fighters. They repulsed the Ambonesian security guards and killed 15 of them. After this incident, the FPI began to recruit new members. A week later, when Christians in Kupang , the capital of the Indonesian province of Nusa Tenggara Timur , burned down mosques and also killed some Muslims, the FPI issued a statement in which it strongly condemned these actions.

In addition, the FPI demanded that human rights violations against Muslims be dealt with during the Orde Baru period. The FPI leadership sees this period very negatively: The government was dominated by Christians and with their help a Christianization of Indonesia took place. 80 percent of the bribery offenses of officials during this time were committed by Christians. On March 29, 1999, the FPI issued a public statement calling for an investigation into the role of Christian General Leonardus Benyamin Moerdani in connection with certain civil unrest. This referred to the Tanjung Priok massacre , an incident in September 1984 near Jakarta in which the Indonesian army killed large numbers of Muslims. The army was commanded by Moerdani.

On January 10, 2000, 200 FPI members held a demonstration in front of the headquarters of the National Commission for Human Rights (Komnas HAM) in Menteng Jakarta, demanding that it be disbanded. On the occasion they hung up a banner on the building that read : "The Komnas HAM is sealed by the FPI" (Komnas HAM Disegel oleh FPI) . The FPI criticized the fact that the commission 1. ignores human rights violations against Muslims, as in the Muslim-Christian conflicts on Ambon, the massacre of Tanjung Priok and the military operation in Aceh and 2. focuses solely on human rights violations in East Timor and only Muslim top generals suspicious. She viewed this as discrimination against Muslims. In addition, the FPI demanded the dismissal of five members of the commission who it considered to be the cause of the problem. Because of the large number of Christians represented on the commission, the FPI was of the opinion that this body was partisan.

The FPI sees Indonesia's Muslims as being threatened primarily by Christianity. In a position paper that the organization adopted at its first national assembly in December 2003, the FPI is asked to take measures to prevent Christianization. Several of the previous FPI actions were also directed against Christian churches. On November 2, 1999, several hundred FPI activists set fire to a Protestant church south of Jakarta. In addition, the FPI repeatedly took action against so-called “wild churches” (reja liar) , churches that were built in Muslim settlement areas without permission. In June 2007, the FPI attacked an Assemblies of God church in Katapang, Soreang, West Java . On August 8, 2010, hundreds of FPI supporters attacked members of the Christian Protestant Batak Church (HKBP) in Bekasi during the service. When the worshipers went home, they were followed and beaten by the FPI supporters. The FPI was of the opinion that the HKBP church had been improperly established and had already disrupted the service several times.

Rizieq Syihab, however, protests against the accusation that the FPI is intolerant and is hostile towards the unbelievers . Rather, the FPI holds the principle expressed in sura 109: 6 “You have your religion, and I mine” very highly. After the suicide attacks on three churches in Surabaya in May 2018, the FPI published a press release in which it criticized these attacks and stated that it opposed terrorist violence against other religious communities. At the same time, however, she also called on the public not to associate the attacks with any particular religious doctrine and its followers.

Anti-communism and anti-Zionism

Since it was founded, the FPI has viewed communism in particular as an enemy. When the FPI first appeared in public on September 24, 1998, it did so with an attack on student activists at the Catholic Atmajaya University. This was intended to challenge "leftist and Christian students who are funded by American Jews". In the early days, the FPI had its own committee that was responsible for the infiltration of student organizations that were viewed as “communist”. In March 2000, she held a rally in central Jakarta where she displayed banners with slogans such as, “We are ready to slaughter communists” and “We are ready to behead communists.” In March and April 2001, the FPI adopted participated in a campaign of anti-communist actions in which left-wing students were attacked and bookshops selling socialist literature were ransacked. On one of its websites, it describes itself as an anti-communist organization. According to Rizieq Syihab, the FPI sees it as obvious stupidity and aberration when a Muslim orientates himself towards the prophet in prayer, fasting and pilgrimage, but in social theory towards Karl Marx , because for the FPI Mohammed is a perfect example not only in worship and interpersonal relationships, but also in politics.

To this day, anti-communism is an important element of the FPI ideology. In January 2017, Rizieq Shihab gave a speech calling on the government to withdraw the newly issued rupiah banknotes because they had an image that resembled the hammer and sickle symbol of the defunct Indonesian Communist Party.

Anti-communism was linked to anti-Zionism from the start . In 1999, the FPI hung a banner in front of the Tarumangara University campus with the text: “Caution! Zionism and communism have invaded every area of life. ”Rizieq Syihab describes the FPI as an organization with an anti-Israel orientation. The FPI regards Israel as a colonial power in Palestine and justifies the fight against Israel with the Indonesian constitution, which defines the fight against colonialism as a national duty in the preamble. The FPI even introduced itself as an anti-Jewish organization on one of its websites.

The FPI's anti-Israel activities peaked between 2000 and 2002. On October 1, 2000, the FPI issued a statement calling for the liberation of al-Aqsa Mosque , i.e. H. of the Jerusalem Temple Mount , demanded. After the Inter-Parliamentary Union announced that it would hold its 104th conference in Jakarta , on October 10, 2000, hundreds of FPI fighters announced their readiness to kill the members of the Israeli delegation that was to attend the conference. The FPI threatened to block Soekarno-Hatta Airport in the event that the organizers of the conference held on to an invitation from the Israeli delegation. On March 22 and 25, 2002, the FPI issued public statements calling for a ban on all trips to Israel that are not related to the efforts to liberate al-Aqsa Mosque, as well as a ban on entry for Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres . In the days that followed, the FPI militia carried out anti-Israel patrols at international airports and tourist spots.

Fight against sin, areas of justice, prohibition of reprehensible

The FPI was founded after Rizieq Syihab as a national anti-Maksiat movement in order to realize the Koranic principle of amar ma'ruf nahi munkar . The Indonesian term maksiat is derived from the Arabic word maʿṣiya , which denotes the violation and opposition to the commandments of God as well as sin. In the early days of Maksiat, the FPI primarily understood the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages, gambling and prostitution . The reason for the founding of the organization was that Maksiat was rampant in Indonesia in all areas of life and had reached an unacceptable level. The aim of the FPI is to anchor the national anti-maksiat movement in all areas of society by using the various means of communication.

The fight against Maksiat also played a large role in public statements by the organizations. In December 1998, during a demonstration, the FPI called for all Maksiat sites to be closed during the month of Ramadan. At a meeting with the Governor of Jakarta in November 1999, a delegate from the FPI said: “We, the Islamic umma , feel it is impossible to find the peace necessary for fasting, according to the tenets of our faith, while these places of opposition are in place (tempat maksiat) exist in our society. ”In the early 2000s, the FPI also made a public statement to the Indonesian government and parliament requesting that 1) public advertising for Maksiat activities be banned ; 2) companies that engage in overtly reprehensible practices will be closed; and 3) companies that are likely to engage in often reprehensible practices will be closed at least on Islamic holidays. The FPI also called on the president and central government to introduce an anti-maksiat law. Rizieq Syihab justifies the limitation of her demand for the closure of dubious companies to the Islamic holidays with the fiqh maxim : "What one cannot fully achieve, one should not drop completely" (mā lā yudrak kullu-hū lā yutrak kullu-hū ) . Overall, the FPI demands that companies with "dubious activities" close 98 days of the year, namely on all Fridays during the month of Ramadan, in the first seven days of Shawwāl , during the six days of Hajj and on Islamic New Year's Day, on schūrā Day, on the Prophet's birthday , on the 27th Rajab and on the 15th Shabān .

In the fight of the FPI against Maksiat, the enforcement of the Islamic alcohol ban is of particular importance. One of the earliest actions to do this came on December 13, 1999, when 30 FPI members confiscated 1,500 bottles of spirits from a warehouse in southern Jakarta in order to force the trader to stop selling alcoholic beverages. They then took the bottles to the local police station. On May 5, 2000, 3,000 FPI fighters demonstrated in Pamekasan and threatened to set fire to hundreds of shops selling alcoholic beverages. One of the usual activities of FPI activists is tearing down billboards for alcoholic beverages. Another important aspect of the FPI's ideology is the fight against gambling (practice perjudian) . In the opinion of the FPI, the Islamic ban on gambling also includes the drawing of tickets in lotteries . In May 2004, for example, the FPI held a rally in which it called for the cancellation of a lottery game at Metropolitan Magnum Indonesia.

The theological basis for the fight of the FPI against Maksiat is the doctrine of the domain of the right and the prohibition of the reprehensible (al-amr bi-l-maʿrūf wa-n-nahy ʿan al-munkar) . As early as December 1998, the FPI issued a declaration in which it declared its support for all citizens who exercise this principle. Rizieq Syihab has written his own book on this principle, which contains a comprehensive theological justification for the violent actions of the FPI and tries to show that these are in accordance with the teaching of Muhammad . In the book, Rizieq Syihab writes that the FPI was founded as an organization for the collaboration of ʿUlamā ' in the execution of amar ma'ruf nahi munkar (AMNM) in all areas of life and positioned itself as an AMNM organization.

According to Rizieq Syihab, AMNM means making systematic efforts to encourage Muslims to fully comply with the precepts of their religion and to prevent them from committing acts that destroy their morality and belief. Since other Islamic organizations in Indonesia such as the Nahdlatul Ulama , the Muhammadiyah and the Indonesian Council for Islamic Daʿwa (DDII) do not implement the principle of the domain of the right and the prohibition of the reprehensible, the need to establish a separate organization for this was seen. When carrying out AMNM measures, the FPI adheres to the classic Hisba rules. For example, it limits the prohibition of reprehensible things to reprehensible things that are clearly revealed and clearly proven. In the latest version of its statutes, the FPI also explicitly uses the term Hisba instead of the expression “territories of the right and prohibition of the reprehensible.” Muchsin al-Attas, the current chairman of the FPI, emphasized in 2014 that the FPI amar ma'ruf nahi munkar also try to enforce in the areas of politics, economy, society and education.

Introduction of Sharia law in Indonesia as a political goal

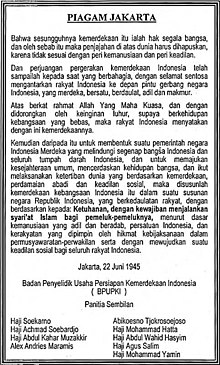

Since 2000 the FPI has been calling for the restoration of the Jakarta Charter , which obliges Muslims in Indonesia to obey Sharia law . In August 2000, it published a statement on this and held a Jakarta Charter parade in which the FPI activists marched in front of the Indonesian parliament. In a book published in October 2000, Rizieq Syihab argued that the omission of the Jakarta Charter by Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta in August 1945 was a betrayal of democracy and an overturning of the constitution. Reintroducing the seven words of the Jakarta Charter into the constitution is a medicine that will restore their stolen rights. In this way a chronic ideological conflict could be resolved. In order to emphasize its demand for the reintroduction of the Jakarta Charter, the FPI held “Islamic Sharia Parades” (Pawai Syariat Islam) in August 2000 and 2001 . The slogan at the FPI rally in August 2001 was: "Better to die defending Sharia than to live without Sharia."

In a policy text posted on the FPI website in 2007, Rizieq Syihab stated that the FPI was a kind of pressure group in Indonesia urging state leaders to “improve the morals and beliefs of the Muslim community and harm it and at the same time to set in motion the construction of a social, political and legal order that is in line with the values of the Islamic Sharia. ”The application of the Sharia in Indonesia, both substantively and formally, is the vision that the FPI wants to implement. Implementing Sharia law means, for example, introducing laws that clearly prohibit prostitution . The aim of the FPI is the "application of Islamic Sharia in a comprehensive way" (penerapan syariat secara kâffah) . A passage in the new version of the FPI-Stauten, quoted by Gumilang, explains that the application of the Sharia “in a comprehensive way” means its application in all areas of life. H. in Akidah , the Ibadah , marital relationships, interpersonal relationships (Muamalat) and the Criminal Law (jinayat) . According to Rizieq Syihab, the AMNM is the lever used by the FPI to implement the values of Sharia law in Indonesia. It represents the alternative way chosen by the FPI to apply Sharia law.

However, Sobri Lubis, the FPI General Secretary, stated in an interview in 2001 that the struggle for the application of Sharia law was being carried out constitutionally. In contrast to other Islamist groups that operate in Indonesia, such as Hizb ut-Tahrir and Majelis Mujahedin Indonesia, the FPI is loyal to the Republic of Indonesia and has never questioned the presence of this state. The founding of the organization on the 35th anniversary of the Indonesian declaration of independence already expresses this. This loyalty is also evident in many of their documents and in the oath that FPI members swear. Every year on Independence Day, thousands of FPI members flock to the city with the red and white flag of Indonesia . This flag has a special meaning for the FPI because, in their opinion, it is based on a hadith , according to which an invincible Islamic state with a red and white flag should emerge at the end of time. The FPI also advocates the 1945 Constitution and Pancasila as the ruling ideology of the state. However, the FPI argues that the actual Islamic foundations of the pancasila have been misunderstood. At a public event in Bandung in February 2012, Rizieq Syihab summed it up in drastic terms: "With the Pancasila of Sukarno, belief in God is screwed, while with the Pancasila of the Jakarta Charter it is in the head" (' Pancasila Sukarno ketuhanan ada di pantat, sedangkan Pancasila Piagam Jakarta ketuhanan ada di kepala ').

Since 2013, FPI has been using the catchphrase NKRI Bersyariah (“The unitary state of the Republic of Indonesia based on Sharia ”) for its state concept . NKRI ( Negara Kesatuan Republic of Indonesia = "Unified State of the Republic of Indonesia") is an abbreviation that is mainly used by the Indonesian military for the state of Indonesia and is associated with efforts that lost its central role in the country after the collapse of the Suharto regime Regain state. The concept NKRI Bersyariah assumes that the Sharia is compatible with the principles of the Indonesian state.

Anti-americanism

Rizieq Syihab describes the FPI as an anti-American organization that openly opposes "US hegemony". The anti-American orientation of the FPI first became apparent after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 , when the organization used the widespread opposition to Washington's war on terror to mobilize larger numbers of supporters. On October 8, 2001, the FPI called for a jihad "against US aggression against Afghanistan". A little later, on October 15, with the support of foreign donors, she organized a demonstration against the imminent US invasion of Afghanistan in front of the Indonesian parliament, which was attended by around 10,000 supporters. On this occasion, the FPI threatened to close the American embassy and demanded that diplomatic relations with the "terrorist state" USA be broken off.

In November 2001, the American Time magazine published a report that covered the FPI's threats against US citizens and alleged that the organization was receiving financial support from the al-Qaeda network. This report sparked great indignation among Rizieq Syihab. In his FPI book, which he published for the first time in 2004, he replied that everyone knew that the United States and England were the greatest terrorist and that they always fought against Islam. In 2004 the FPI organized demonstrations against George W. Bush's visit to Indonesia. In addition, she chose the motto “Apply Sharia - Avoid Sins - Fight the USA” (Tegakkan Syari'at - Tolak Ma'siat - Lawan America Serikat) for the parade on the anniversary of its foundation in August 2004 .

A new wave of anti-American FPI demonstrations occurred when the American President Donald Trump recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel in early December 2017. In response, the FPI held a protest rally in front of the US embassy in Jakarta on December 11, 2017. American flags were also burned on this occasion. The FPI also threatened to destroy the US embassy. In May 2018, the FPI again called on Muslims to take up arms and attack the US embassy.

Defending the Prophet and His Family

The FPI has been active several times in the past to defend the Prophet Mohammed and his family against alleged insults. On February 3, 2006, hundreds of FPI members gathered in front of the Danish embassy in Jakarta and protested against the publication of the Muhammad cartoons . Three days later, on February 6, hundreds of FPI members from East Java protested the cartoons in front of the Danish consulate in Surabaya . The demonstrators then tried to get to the US consulate to protest against the representation of Muhammad on the United States Supreme Court Building . The FPI regards this representation, although it is supposed to honor Mohammed as a legislator, as an insult to Islam. On February 19, 2006, hundreds of FPI members again protested in front of the US Embassy in Jakarta against the depiction of Muhammad in the Supreme Court building. They carried banners with inscriptions such as “Stop the depiction of the Messenger of God” (Stop Visualsiasi Rasulullah) and “Come, destroy the offenders of the Messenger of God” (Ayo Ganyang Penghina Rasulullah) . They also requested the removal of the relief on the building that depicts the prophet Moses .

A few years earlier, in May 2001, FPI supporters attacked the headquarters of the television broadcaster SCTV because it had broadcast the telenovela Esmeralda , in the plot of which a malicious woman named Fatima appears. The FPI saw this as an insult to the daughter of the prophet of the same name, Fātima bint Muhammad, and asked the television station to stop broadcasting the telenovela. In early July 2018, 9 FPI members attacked Surabaya Zoo because the zoo staff named a young camel Āmina, which was also the name of Muhammad's mother . The leader of the FPI militia in Surabaya justified the attack by saying that it was immoral to name an animal after the mother of the Prophet. The zoo admitted to the media that it had made a mistake and changed the name of the animal.

The fight against sexual permissiveness and "pornography"

The fight against sexual permissiveness and “pornography” also plays an important role in the ideology of the FPI. As early as July 1999, 500 FPI members marched in front of the headquarters of the capital city police and demanded measures against gambling and pornography . In the policy text published on the FPI website in 2007, Rizieq Syihab explains that the FPI combats all forms of social crime (kejahatan sosial) that are structural in nature and threaten Muslim society. This includes pornography and the gambling industry. On its website, the FPI campaigns for approval with the argument that it "teaches fear to prostitutes, transvestites (Waria), drunkards, gamblers, adulterers and other sinners."

The FPI rejects all types of beauty pageants , be it for women or transvestites (waria) . On June 27, 2005, FPI activists attacked a transvestite beauty pageant at Sarinah House in Jakarta. In September 2005, the FPI charged several Indonesian actors with pornography for posing naked for a work of art that was shown at the Centerpoint Biennale in Jakarta. On April 12, 2006, 150 to 200 FPI supporters destroyed the editorial office of the Indonesian edition of the men's magazine Playboy in South Jakarta and set it on fire after a leading FPI member had previously reported the publisher Erwin Arnada and two Playboy models to the police for shamelessness had indicated. In June and July 2006, the FPI then announced further Playboy models. Other actions that go in this direction were the sealing of the Fahmina Institute in Cirebon , which rejected the draft law against pornography and pornography campaigns, on May 21, 2006 and the demonstration in front of the Maxima Picture production house, which the Japanese porn actress Maria Ozawa wanted to invite on October 9, 2009.

Another enemy of the FPI is the LGBT movement. On September 28, 2010, supporters of the organization marched in front of the Goethe Institute in Jakarta and ultimately demanded the termination of the queer Q! Film festival supported by this institute with the argument that the promotion of free sex, sexual deviation, homosexuality and Lesbianism must be stopped. On May 4, 2012, the FPI protested outside the Salihara Theater in Jakarta, while the liberal Canadian Muslim activist Irshad Manji presented her new book Allah, Liberty, and Love . When she had spoken for 15 minutes, she was interrupted by the police, who said that the event had to be canceled because hundreds of FPI supporters had gathered to call for an end to the event. Habib Novel, the general secretary of the FPI in Jakarta, commented on the action the following day: “Irshad Manji is a gay and lesbian activist. She wants to open Islam to gays and lesbians. However, Islam will never accept gays and lesbians. ”The government then expelled Manji from the country, arguing that it was trying to promote homosexuality among Indonesian Muslims. At the same time, the FPI threatened to mobilize 30,000 of its members to prevent a Lady Gaga concert that was scheduled for early June 2012 at the Gelora Bung Karno Stadium . Lady Gaga then canceled her concert.

The FPI is campaigning for women to wear jilbāb clothing in all government institutions . She considers jilbāb bans in hospitals and in the army and police to be illegitimate. She rejects bans on polygamy , female circumcision and marriages with underage girls, as demanded by international organizations, as “anti-Islamic programs”. She believes it is legitimate for girls to be married as soon as menstruation has started.

Jihad and Martyrdom

According to Rizieq Syihab, the designation as Front Pembela Islam should give the organization a combat identity (identitas perjuangan) . The priority of the FPI's struggle is the “war on sin” (perang melawan ma'siat) . The fighting philosophy (filsafat juang) of the FPI says, according to Rizieq Syihab: "For the mujahid , slander is a habit, killing is martyrdom, imprisonment is seclusion and displacement is travel." This philosophy should not only increase the willingness of the FPI activists to take risks, but also make toil and suffering bearable for them.

As Rizieq Syihab explains in his book on the FPI, the FPI has adopted the five principles of the Islamic struggle from Hasan al-Bannā , the founder of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood , and made them its guiding principle. The five principles are: 1. God is our Lord and goal; 2. Mohammed , the Messenger of God, is our power; 3. the noble Koran is our guideline ; 4. Jihad is our way; and 5. Martyrdom is our goal. In the FPI, jihad is understood primarily as a struggle to realize what is right and to prohibit what is wrong. The independence of responsibility is important for the identity of the FPI's struggle. This means that every FPI activist takes on the full moral and legal action for the AMNM actions that he carries out himself and also all associated risks, without being allowed to involve other activists.

The great importance of martyrdom is particularly evident in the FPI's slogan. It reads: "Live venerably or die as a martyr" (Arabic: ʿIš karīman au mut šahīdan ; Indonesian: Hidup mulia atau mati syahid ). As Rizieq Syihab explains, this slogan comes from Sayyid Qutb . He is said to have said this before he was hanged by the Nasser regime. The five principles of the Islamic struggle and the FPI slogan also form the main content of the text of the FPI march, which the FPI uses as one of its identifying marks.

At the international level, the FPI sees it as its task to support the jihad fighters in Palestine, Iraq, Afghanistan, Chechnya, southern Thailand, southern Philippines, Mindanao , Kashmir and other parts of the world. At the time of the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, the FPI opened recruiting offices for jihad fighters who wanted to go to Iraq at its headquarters in Tanah Abang ; more than 5000 people answered.

On August 8, 2014, the FPI published a five-point declaration on the IS organization in which it expressed its loyalty in supporting the Islamic jihad movement around the world "in the fight against all forms of tyranny of global hegemony (New Imperialism) “Announced. However, it rejects sectarian violence and warfare between Muslims on the basis of madhhab differences that are not rooted in the foundations of religion (ushuluddin) and does not allow these to be called jihad. In its declaration, the FPI calls on all Islamic jihad movements to unite and support one another in carrying out Sharia-compliant jihad without killing or mistreating civilians who are not involved in the war, regardless of theirs Madhhab and their religion. In the last point, the FPI expresses its support for the appeal of al-Qaeda leader Aiman az-Zawahiri , who supports the jihad groups of Abu Muhammad al-Jaulani in Syria, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in Iraq and other groups from Al-Qaeda had called to unite and fraternize with all other Islamic mujāhidūn worldwide in order to continue the jihad in Syria, Iraq, Palestine and other oppressed Islamic countries. The declaration is signed by the FPI Chairman Muhsin al-Attas, Rizieq Syihab and the FPI General Secretary and, as stated in the last sentence, is addressed to all FPI leaders, activists, fighters, members and sympathizers of the FPI worldwide.

Ahmadiyya and liberal Islam as enemy

Since 2007 the FPI has been agitating against the Ahmadiyya and liberal Islam. The FPI believes that Islam has been betrayed by the Ahmadiyya and liberal reformers such as Nurcholish Madjid and Abdurrahman Wahid and the Liberal Islam Network ( Jaringan Islam Liberal ; JIL). On February 14, 2008, Sobri Lubis, then General Secretary of the FPI, declared war at a large gathering of the Ahmadiyya Organization. At this meeting in a pesantren in Kota Banjar, West Java, he said, “If the government does not eliminate the Ahmadiyya, we will call on Muslims to fight against the Ahmadiyya supporters: kill them wherever they live ... kill them. This is because you, Ahmadiyya, violate our beliefs. Their blood may be shed. ”On this occasion, Sobri Lubis also explicitly acknowledged his responsibility for this call to kill the Ahmadiyya. In July 2008 the FPI published a declaration in the magazine Suara Islam ("Voice of Islam") to prove the Ahmadiyah's disbelief (Maklumat FPI tentang bukti kekafiran Ahmadiyah) .

The FPI has already acted violently against the Ahmadiyya on several occasions. On June 20, 2008, a local FPI contingent forcibly closed the Ahmadiyya headquarters in Makassar . And on April 20, 2012, an FPI group attacked an Ahmadiyya mosque in Tasikmalaya, western Java. The FPI's aggression in the Monas incident (see below) was also directed against the Ahmadiyya.

As far as liberal Islam is concerned, the FPI declared in its 2007 declaration that attempts to liberalize the teaching of Islam from within the Islamic community itself must be resolutely opposed. An FPI banner that was seen near the FPI headquarters in Jakarta in 2012 read: “Liberal is not Islamic, Islam is not liberal.” Another FPI poster read: “Destroy the Liberals. Dissolve the Ahmadiyya. Liberals and Ahmadiyya are stray people, apostates , infidels , but not Islam. ”Liberal Muslims and Mirza Ghulam Ahmad , the founder of Ahmadiyya, are depicted on the poster as the vampire-like forces of Satan .

Since 2008 , the FPI has viewed secularism , pluralism and liberalism , which it collectively abbreviates as SEPILIS in reference to the disease syphilis , as “imported negative ideologies” that must be eradicated and removed from state teaching materials. Rizieq Syihab stated in a fatwa that it is forbidden to vote for political parties that are SEPILIS-oriented or that do not support the dissolution of the Ahmadiyya. An action by the FPI, which specifically served to combat pluralism, was your protest against the broadcast of the film ? (sic!), which deals with the concept of religious pluralism in Indonesia. On August 27, 2011, one hundred FPI supporters gathered in front of the SCTV headquarters in Senayan and demanded that the broadcast of the film be stopped.

Endeavor to establish an international Islamic caliphate

At its second National Assembly in 2008, the FPI decided that the organization should play an active role in the establishment of an international Islamic caliphate “in accordance with Sharia law” through “elegant and responsible logical and realistic steps” that “lead to the progress of the Fit the world ”. This should include:

- Strengthening the function and role of the Organization for Islamic Cooperation ,

- Formation of a common parliament of the Islamic world,

- Formation of a common market for the Islamic world,

- Formation of a common defense pact for the Islamic world,

- Unification of the coins of the Islamic world,

- Abolition of passports and visa requirements within the Islamic world,

- Facilitating marriages within the Islamic world,

- Standardization of school curriculum, especially in the area of religious education, within the Islamic world,

- Establishing a common satellite system for communication within the Islamic world,

- Establishment of an International Islamic Court of Justice.

In its declaration of August 2014 on the IS organization, the FPI defined the “establishment of the Islamic caliphate through Daʿwa, Hisba and Jihad according to the model of prophecy (sesuai Manhaj Nubuwwah) ” as its vision and mission. With this expression she has aligned herself with the IS organization, because this organization also calls her caliphate the caliphate “according to the model of prophecy” (ʿalā manhaǧ an-nubūwa) .

In a YouTube video entitled “The FPI and the Islamic Caliphate”, which the FPI published in June 2015, it committed itself even more clearly to the concept of the caliphate. In the version of the FPI statutes shown in the opening credits of the video, the vision and mission of the FPI is stated: “The application of Islamic Sharia law in a comprehensive manner under the protection of the Islamic caliphate according to the model of prophecy, through the implementation of Daʿwa, upholding the Hisba and carrying out jihad. ”In a text that is shown in the video afterwards, it is stated that the Islamic caliphate that the FPI is fighting for is not the abolition of the Republic of Indonesia and other states such as Saudi -Arabia, Egypt, Yemen, Turkey, Pakistan, Malaysia and Brunei mean, but rather the expansion of the cooperation relations of all Islamic countries, especially those that are united in the Organization for Islamic Cooperation, in order to remove all obstacles that stand between these countries, to eliminate. In his speech, Rizieq Syihab makes it clear that he sees the European Union and NATO as models for the Islamic caliphate. Unlike the organization Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia , which is also working towards a caliphate, the FPI does not reject the existing states because it is more realistic. Despite this strategic direction, the FPI will remain loyal to the Republic of Indonesia, which is based on the Pancasila and the 1945 constitution. Indonesia will even take over the leadership of the Islamic world in the future, because it is the largest Islamic country and most Muslims live in it.

Clarification of the dogmatic position: Between Shiites and Wahhabis

Some scientific authors have described the FPI as a Salafist organization. According to Al-Zastrouw, the teaching of the FPI is close to the Salafism of the Laskar Jihad group led by Ja'far Umar Thalib. However, this classification cannot be maintained, because the statute of the FPI mentions that the organization follows the Ashʿarīya in the ʿAqīda and the Shafiite teaching direction in Fiqh . Salafist teaching, on the other hand, rejects such affiliations. Rizieq Syihab himself says in his FPI book that there is no place in the FPI for opponents of Madhhab because the FPI venerates the imams and followers of the various disciplines. In addition, litanies of Tarīqa ʿAlawīya are recited at the weekly teaching sessions of the FPI on Thursday evenings . To the prayers that the FPI for solicitation of divine assistance (istiġāṯa) recommends that belongs invocation of hadramautischen Sufis Abu Bakr ibn Sālim (d. 1584). This shows that the FPI has a more Sufi orientation.

After repeatedly speculating about the dogmatic orientation of the FPI and accusing it of being a Wahhabi organization, the FPI published its dogmatic position and its position against Shiites and Wahhabis in a text published on its website in 2010 clarified. The text is based on a statement that Rizieq Syihab made at an FPI training day in late 2009. Accordingly, the FPI is committed to the doctrine of the Sunnis (Ahlusunah Waljemaah) and follows the Shafiite teaching direction in Fiqh . She is neither Shiite nor Wahhabi.

As far as the FPI's point of view towards the Shiites is concerned, it distinguishes between three groups: 1. The ghouls who deify ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib and who consider the Koran to be falsified ; 2. the Rāfidites , who slander the Sahāba such as Abū Bakr and ʿUmar ibn al-Chattāb and the wives of the prophets such as Aisha bint Abī Bakr and Hafsa bint ʿUmar ; and 3. The moderate Shiites, the ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib and the traditions of the Ahl al-bait give special priority, but treat the Sahāba with respect, even if they criticize them. While the first group, in the opinion of the FPI, fights as unbelievers, and the second group must be rebuked, the third group should be met with Daʿwa and dialogue. Here the FPI cites the scholars Muhammad Saʿīd Ramadān al-Būtī , Yūsuf al-Qaradāwī , Wahba az-Zuhailī and ʿAlī Jumʿa , who have declared the moderate Shiites to be a recognized Islamic discipline. In the same way, the FPI distinguishes between three groups among the Wahhabis. The first group are the Takfīrī Wahhabis, who declare all Muslims who do not agree with their views to be unbelievers and ascribe physical attributes to God; they are to be fought as unbelievers. The second group were Wahhabi Kharijites who insulted the Prophet's family. This group has strayed; she must be confronted and corrected. Finally, there are the moderate Wahhabis who do not hold any Kharijite or Takfīritic positions. One must approach these in dialogue and in Islamic brotherhood.

organization structure

The “Grand Imam”: al-Habib Rizieq Syihab

At the head of the FPI has been the scholar al-Habib Muhammad Rizieq bin Hussein Syihab (born August 24, 1965 in Jakarta). Habib Rizieq is venerated by his followers as the Imam Besar ("Grand Imam") and has a quasi-holy rank among his followers due to his descent from the Prophet. However, he is also highly regarded by them for his simple and humble lifestyle and courage. The title Habib shows that he belongs to the Habaib (see below), but is also meant to mean that Rizieq is the “darling” (Arabic ḥabīb ) of his followers. The FPI describes itself as the “community of those who love Habib Rizieq Syihab” (Komunitas Pencinta Habib Rizieq Syihab) .

Rizieq's father Sayid Husein was the founder of the Panda-Arab movement, a kind of scout movement for Arab Indonesians. Rizieq Syihab studied at King Saud University in Saudi Arabia from 1984 to 1990 on a scholarship from the Organization of the Islamic Conference and then spent a year at the International Islamic University in Kuala Lumpur . Before founding FPI, he was a preacher and teacher in an Islamic school in central Jakarta . The Third National Assembly of the FPI in 2013 confirmed him in his post as Imam Besar for life.

Habib Rizieq's book Dialog FPI amar ma'ruf nahi munkar: menjawab berbagai tuduhan terhadap gerakan nasional anti ma'siat di Indonesia (“Dialogue FPI, the territorialization of the right and the prohibition of the wrong: response to some accusations against the national anti-sin movement in Indonesia “) Is today the religious standard work for FPI members and contains everything you need to know about the FPI.

After various criminal charges were brought against Rizieq Syihab between the end of 2016 and the beginning of 2017, he fled to Saudi Arabia via Yemen in May 2017. At the end of September 2018, the FPI announced that Rizieq Syihab was in a condition similar to house arrest. He is not allowed to leave his domicile. On September 26, 2018, the FPI asked the Deputy President of the Indonesian Representative Council, Fadli Zon, to contact the National Police Commissioner, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Indonesian Mission in Saudi Arabia to find out the reason for the treatment of Rizieq Syihab.

On November 8, 2018, Rizieq Syihab was arrested by the Saudi police for holding a flag on his home in Mecca that resembled the IS flag. FPI officials alleged on November 9, 2018 that the Saudi Arabian police were looking for perpetrators who are believed to have displayed the IS flag on the home of Rizieq Shihab, and suggested that intelligence services were involved in the case. Rizieq Syihab had previously been detained twice - in 2003 and 2008 - for several months in Indonesia. During his absence, the activities of the FPI declined sharply.

The central management structure

The highest body of the FPI is the National Assembly ( Musyawarah Nasional ; MUNAS), which, however, only meets every five years. So far it has only met three times, namely the first time from December 19 to 21, 2003 in Jakarta, the second time from December 9 to 11, 2008 in Bogor and the third time on August 22 to 24, 2013 in Bekasi . In the meantime, the FPI is headed by the Central Leadership Council ( Dewan Pimpinan Pusat ; DPP), which is composed of two bodies, the Consultative Council (majelis syura) and the Executive Council (majelis tanfidzi) . The consultative council has the task of appointing and advising the chairman of the executive board and of monitoring all activities of the FPI. It consists of five Dīwānen, each of which includes several religious scholars from different regions: 1. the Sharia-Dīwān (dewan Syariah) ; 2. the constructive Dīwān (dewan pembina) ; 3. the advisory Dīwān (dewan penasihat) ; 4. the controlling Dīwān (dewan pengawas) and 5. the honor-Dīwān (dewan kehormatan) . The current chairman of the Consultative Council (2015-2020 period) is KH Misbahul Anam, who previously served as the organization's first general secretary.

The Executive Board, which is responsible for the day-to-day organization, consists of the Chairman, the Secretary General, the Treasurer and various other members with specific responsibilities. According to a report that the FPI published on its website at the beginning of May 2015, the Executive Board for the period 2015 to 2020 consists of the following nine people:

- Chairman: KH. Ahmad Sobri Lubis

- Deputy Chairman: KH. Ja'far Shiddiq

- Secretary General: Haji Hasanuddin

- Treasurer: Ustadh Haris Ubaidillah

- Head of the Daʿwa department: KH. Zainudin Ali

- Head of Hisba Department : Ustadh Slamet Ma'arif

- Head of the Jihad Department : KH. Abdul Qodir AKA

- Head of the Department for Enforcement of the Caliphate: KH. Tb. Abdurrahman Anwar

- Head of Organization Department: H. Munarman

The appointment of Lubis came because the previous chairman Rizieq Syihab was "permanently prevented". The chairman of the executive board is subordinate to various departments, which are supposed to support him in the execution of his office. He also has the right to set up various committees, commissions, and branches as needed.

Since 1999 the head office of the Central Leadership Council of the FPI has been located at Jalan Petamburan III No. 17 in the Tanah Abang district in Central Jakarta.

Branches

At the horizontal level, the FPI is organized in the Central Leadership Council ( Dewan Pimpinan Pusat ; DPP) at the national level, the Provincial Leadership Councils ( Dewan Pimpinan Daerah ; DPD) at the provincial level, and the Regional Leadership Councils ( Dewan Pimpinan Wilaya ; DPW) at the city level and Regencies, the Branch Leadership Councils ( Dewan Pimpinan Cabang ; DPC) in the subdistricts and the command posts at the village level. There is different information about the number of Indonesian provinces in which the FPI is active with its own branches. While Ahmad Sobri Lubis, the general secretary of the FPI, gave it 22 in December 2003, Efendi / Pramuko and Wilson, whose books were published in 2006, speak of 18 and 26 provinces with FPI branches, respectively.

According to Jahroni, many of the FPI branches are closely linked to the headquarters in Jakarta. Rizieq Syihab himself emphasizes, on the other hand, that all regional and local FPI branches operate largely independently and were set up in Jakarta without the help of the Central Management Council. The head office only finances the sending of a delegation to the inauguration and cannot provide any construction assistance. In the past, the two branches in Surakarta and Yogyakarta in Central Java have shown particularly great independence . Front Pembela Islam Surakarta (FPIS) is one of the most active offshoots of the organization and is heavily influenced by the Majelis Mujahidin Indonesia (“Council of Indonesian Jihad Fighters”) from Abu Bakar Bashir . The FPI units outside the capital were notorious in the early days for their militancy, poor coordination and lack of discipline. According to R. Hefner, this has to do with the fact that in the months after Suharto's fall the national organization was brought together through alliances between bosses of already existing paramilitary units, some of which had only nominal connections with the leadership in Jakarta.

Jamaah and Laskar: the dual structure of the FPI

The scientific literature emphasizes that two major organizational structures co-exist in the FPI, Jamaah (“community”) and Laskar (“army, troop”). The Jamaah is responsible for the “area of the right” (Amar ma'ruf) , which manifests itself in the Daʿwa and in encouraging the local population to attend the FPI prayer meetings and to fulfill their religious duties. The Laskar militia, also known as Laskar Pembela Islam (“militia of the Islam defenders”; LPI), is responsible for the “prohibition of the reprehensible” (nahy munkar) .

According to the FPI statutes, which were adopted at the National Assembly in 2003, the LPI militia is one of the four branch organizations (Anakorganasi) of the FPI. The other three branch organizations are the women's branch of the Islamic Defenders (Mujahidah Pembela Islam) , whose activities focus on social issues and are also committed to the principle of Amar bi-l-maʿrūf, the union of the workers' front (Serikat Pekerja Front) and the "Islamic Student Front" (Front Mahasiswa Islam) , which has the task of leading the intellectual struggle in defense of Islam. The LPI is, however, much better known than the other three branches because it has often been involved in violent activities in the past. According to Rizieq Syihab, the LPI is "the spearhead of the FPI's moral struggle".

| The seven hierarchical levels of LPI according to Jahroni | ||

|---|---|---|

| level | Item designation |

Number of subordinates |

| 1 | Imam Besar | All of the military personnel |

| 2 | imam | 26400 people (25000 Jundi + 1250 Rais + 125 Amir + 25 Qaid + 5 Wali) |

| 3 | Wali | 5280 people (5000 Jundi + 250 Rais + 25 Amir + 5 Qaid) |

| 4th | Qaid | 1055 people (1000 Jundi + 50 Rais + 5 Amir) |

| 5 | Amir | 210 people (200 Jundi + 10 Rais) |

| 6th | Rais | 20 people |

| 7th | Jundi | 1 person |

The LPI is strictly hierarchical in itself, the hierarchy reflecting the territorial command structure of Indonesia 's armed forces , with a chain of command that extends from the national level down to the subdistricts. According to Jahroni, the FPI's military command structure is divided into a total of seven hierarchical levels:

People wishing to join the LPI typically go through three days of paramilitary training. This usually takes place in Bumi Perkemahan Karang Kitri in Bekasi . After the training is over, the new members have to speak the Baiʿa . It reads: "Ready to give up sinful behavior (maksiat) , ready to defend oppressed Muslims, ready to die as martyrs in God's way " (Siap meninggalkan maksiat, siap membela muslim yang dizalimi, siap mati syahid di jalan Allah) . The militia is not armed with firearms, only with knives and swords. When a member of the LPI dies, all other members are required to attend to their funeral.

The members

According to its statutes, any Muslim who has a good character, is godly , possesses the spirit of jihad, is brave and has a high sense of loyalty can become a member of the FPI . With regard to the number of members of the FPI, there are very different statements. Efendi / Pramuko and Rosadi speak of 7 million members for 2006 and 2008 respectively. Muchsin Alatas, the former FPI chairman, named the same number in 2014. In August 1999, Rizieq is said to have claimed to have a total of 13 million followers. The number of followers in Western scientific literature, on the other hand, is considerably lower. According to Robert Hefner, the organization had only 40,000 to 50,000 active members in 2004, most of whom were concentrated in a handful of larger cities. According to Ian D. Wilson, the number of followers in 2006 was 100,000. Ahmad Sobri Lubis, the general secretary of the FPI, stated in December 2003 that the FPI had around 870,000 members. According to a survey by Lembaga Survei Indonesia in 2007, 0.7 percent of all Indonesians were members of FPI. With a total population of 232.5 million in Indonesia, this corresponds to a number of 1.6 million.

The uncertainty regarding the number of members is related to the fact that the FPI has more of the character of a community or movement than that of an organization and cares little about formalities. Accordingly, membership is hardly formalized: In contrast to being accepted into the LPI, admission into the organization takes place without Baiʿa and without organizational procedures. If someone takes part in the activities of the FPI, they are considered an FPI member. The main bond that unites FPI members is their dedication and loyalty to the leader. People who are accepted into the organization are usually known to another FPI member beforehand. In addition to this informal way of recruiting members, there is a more formalized way of laying out and distributing registration forms for new members in universities and religious schools, but this is more of an exception.

Distinguishing marks: FPI logo and FPI uniform

The FPI has its own logo, which is intended to remind FPI activists of the character of their organization. It consists of a five-pointed star surrounded by an isosceles triangle prayer chain . Above the star there is a crescent moon, below is al-Ǧabha al-islāmīya ad-difāʿīya ("Islamic Defense Front ") in Arabic script , below it in Latin script Front Pembela Islam . The star is formed from the Shahada , the crescent from the Basmala . The star, crescent and prayer beads are green, the writing is black and the background is green. The triangle is intended to indicate the strength of the bond of brotherhood, the prayer beads to the Dhikr and religiosity, its 99 pearls to the beautiful name of God , and the dome-like shapes in the three corners to the attachment of the FPI members to the mosque. The five points of the star symbolize the five pillars of Islam and the five compulsory daily prayers. The white background is supposed to symbolize purity, the green color Islam and the black color of the writing on determination in battle. The Arabic lettering should refer to the “Spirit of the Koran” (semangat Qur'an) , the Indonesian lettering to the love for the fatherland.

The FPI also has its own uniform. It consists of a shirt and long trousers in white color and a pilgrim's cap or a turban also in white, which are completed by a scarf and a sash or a belt buckle in green color. Rizieq Syihab calls this uniform Taqwā clothing and declares that it should morally strengthen FPI activists and, conversely, demoralize their opponents. Wilson says that it resembles traditional Arabic clothing and is based on popular representations of the Wali Songo, the nine Muslim saints who are said to have spread Islam in Java . Efendi / Pramuko, on the other hand, emphasize that the FPI wants to use this clothing to express that it has a police-like character. In most of their actions, the FPI members identify themselves with this uniform with the green FPI label and the FPI logo.

financing

For their own financing, some branches of the FPI levy membership fees from their members. In addition, FPI often receives donations from outside donors for their demonstrations. Rizieq Syihab himself writes that the willingness to sacrifice one's fortune for the FPI's struggle has been the most important model of funding since the organization was founded. The principle of financing the FPI is the principle: “By the umma , through the umma and for the umma.” All AMNM activities, explains Rizieq Syihab, are financed through joint contributions of the FPI activists. From time to time there is also support from FPI sympathizers. However, the FPI has no external donors who are permanently involved in the financing of the organization. In the report that the FPI submitted for its Second National Assembly in 2008, it stated that the amount of donations for the FPI in the years since 2003 has been very low. Even the amount of money for the purchase of the small building in Petamburan in which the FPI Secretariat is located was difficult for the FPI to raise. Until 2008 the loan had not been paid off. After Hasani / Naipospos, the FPI opened individual companies. In addition, she receives income from the sale of her uniforms and attributes.

activities

Munajat, who carried out a more extensive study of FPI activities from 1998 to 2010, found that more than half of these activities took place in Jakarta, while the rest were spread across the zones of influence of other FPI associations. The Jakarta Association is thus by far the most active of all FPI associations. Overall, the FPI activities can be divided into the following categories:

Sweeping: The fight against sin

According to Munajat, a total of 45.5% of all activities of the FPI fall into the category "Action against immorality / Maksiat". Activities of this kind took place shortly after the organization was founded. On November 7, 1999, 300 masked FPI fighters attacked the Larangan Plaza Hotel in Pamekasan on Madura Island . They broke into the hotel rooms, hunted prostitutes and beat them. As of late 1999, the FPI carried out dozens of attacks on nightclubs, billiard halls, brothels, gambling halls, and other sites of “sinful” activity.

The actions in which supporters of the FPI attack "places of sin", destroy them and threaten the owners, are also called sweeping (literally "turning away, sweeping away"). To a certain extent, sweeping is the implementation of the principle of "prohibiting the reprehensible" (nahy munkar) . During these actions, the FPI supporters are usually armed with batons. In December 2017, for example, four FPI members armed with batons broke into a hotel in Klaten, central Java, and hunted down unmarried couples there. In February 2012, the Tangerang FPI threatened sweepings against small supermarkets selling alcohol. The local leader of the FPI described the sweeping as "procedure in the style of the FPI" (penertiban ala FPI) . On the eve of Ramadan 2012, the FPI also carried out a spirits sweeping in several regions of Bandung .

Sweeping actions are preferably held in the month of Ramadan because this most strongly symbolizes the purification of the Islamic community. During Ramadan 2002 alone, 20 such actions took place. Activities usually begin in the evening after the Tarāwīh prayers. For example, the FPI of East Kalimantan carried out a comprehensive sweeping action in Samarinda in Ramadan 2007 . First a car convoy drove through the city and called on the people to “preserve the holiness of Ramadan”. FPI supporters then went en masse to the banks of the Mahakam River, drove couples apart and searched parked vehicles. Later, the FPI supporters engaged in a chase with young people they had caught drinking alcoholic beverages on the roadside. A young man they found drunk in Harapan Baru beat them. After dispersing other teenagers they found drinking, they demolished a large party tent and set it on fire. The FPI supporters threw stones at the people who had celebrated in the tent, so that they eventually fled. The local FPI chairman said after the incident that the supporters had originally only intended to conduct a peaceful convoy. Due to the observed misconduct of the citizens, they would then have been forced to pursue sweeping activities.

According to the FPI leadership, the targets for sweeping actions are identified by a separate commission for monitoring sins. This allegedly follows strict procedural guidelines. She should first check reports from local residents and only then, after confirmation, file a formal report with the police. The LPI militia is responsible for carrying out the sweeping operations. Even if the LPI has not made such a strong impact in recent years, it still exists today. In January 2018, CNN reported that a sweeping action against prostitution in Pamekasan had been coordinated by the LPI General Staff in Jakarta.

Various reports indicate that sweeping activities by FPI members were also used for self-enrichment in the past. Rosadi reports on cases of people collecting money from hotels on behalf of the FPI. According to Al-Zastrouw, operators of entertainment venues in Mangga Besar and Kemang were asked for "donations" (sumbangan) to serve as a guarantee of safety. In the event that the businessmen did not pay these donations, they were threatened with attacks in the name of the fight against Maksiat. In other cases, FPI activists attacked a café and only moved after the café owner handed them a sum of money. When the Indonesian Entertainment Industry Association, Aspehindo, publicly complained in December 2003 that the FPI had destroyed recreational facilities of business people who had refused to pay the FPI money, the FPI reported him to Jakarta Police for defamation. Rizieq Syihab admits in his FPI book that there was collusion between individual FPI members and owners of entertainment venues in 2000 , but argues that the FPI reacted to these incidents by excluding the members concerned. Otherwise, he explains, the actions of the FPI to close Maksiat places followed certain standard procedures, which depended solely on whether the Muslim population in the area had complained to the FPI about the places in question or not.

At the FPI, sweeping is not limited to the “fight against sin”, but is sometimes threatened to achieve other goals. For example, before the American invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, the FPI threatened to carry out sweeping operations at hotels in order to track down American and British spies. In the same way, the FPI threatened sweeping activities against American citizens in Indonesia after the beginning of December Donald Trump announced that he would move the US embassy to Jerusalem.

Protest rallies

Protest rallies are another important activity of the FPI. As a rule, the FPI activists march in front of the headquarters of the organization concerned and use loudspeakers to speak to those responsible in order to express their protest and possibly to demand an apology. At the FPI rally against the National Human Rights Commission in January 2001, FPI members gave speeches in front of the building explaining why the commission had to be dissolved and handing out leaflets. Other FPI members hung a banner on the commission building that read : “The Komnas HAM is sealed by the FPI” (Komnas HAM Disegel oleh FPI) . The action only ended after two members of the commission agreed to meet representatives of the FPI. A member of the commission, Benyamin Mangkoedilaga, then made a statement from an FPI vehicle expressing his approval of the FPI's demands and promising to forward them to the head of the commission. After that, the FPI people left, but on the way back they threw stones into various cafes and bars. During the protests against the publication of the Muhammad cartoons in February 2006, FPI activists protested in Surabaya until ten representatives were allowed to speak to staff at the Danish embassy. However, since they were not satisfied with the conversation, they threw stones, rotten tomatoes and rotten eggs at the consulate.

Pengajian: Religious instruction for members

All FPI members and followers usually attend sessions of Quran recitation (pengajian) and instruction in Islamic teachings hosted by the scholars of the Consultative Council and other FPI leaders. The FPI's Pengajian religious events usually include shalawat, chants accompanied by drums in praise of the Prophet Muhammad. Was the time when Misbahul Anam General, he gave lessons in the rules of jihad (fiqh al-ǧihād) , but also conveyed litanies of Tijaniyyah -Ordens in which he as a spiritual leader (muršid) worked. The Jamaah branch of the FPI is responsible for the organization of the Pengajian activities and the religious education of the members. LPI members usually only take part in the Pengajian meetings in a subordinate role. The connection of people to a specific LPI department depends on which Pengajian teaching circle they participate in.

Before leaving for Saudi Arabia, Rizieq Syihab also held a teaching circle (Majelis Ta'lim) with Pengajian twice a week , on Wednesday in the Al Ishlah mosque in Petamburan in Tanah Abang and on Thursday evening in his own house. These teaching circles could be attended by all members. The audience usually consisted of about 2500 people, making his Pengajian particularly large. Most of the visitors were FPI supporters. They came regularly in motorcycle convoys from other parts of Greater Jakarta. Rizieq Syihab's teaching circle at the Al Ishlah Mosque, which was also open to the general public, also played an important role in recruiting new members. People who had attended this teaching circle and brought the recommendation of another FPI member with them could become members directly. The mosque al Ishlah forms the actual religious center of the FPI and serves as a meeting place for the members at rallies.

Tabligh Akbar and Takbir Keliling: mass religious events

Also important on the religious level are the public sermon events called Tabligh akbar (“Great Transmission”). The FPI activists held such events before the FPI was officially founded. At these mass celebrations, attended by thousands of FPI supporters, the FPI anthem is usually sung and the FPI march played. It was also a Tabligh-akbar event at which Sobri Lubis, the then General Secretary of the FPI, declared war on the Ahmadiyya on February 14, 2008.

Another form of religious mass celebrations are night tours or marches through the city. They are called takbir keliling . On the night of June 13, 2018, for example, the FPI held a takbir keliling around Jakarta on the occasion of the celebration of the breaking of the fast . On this tour, the members of the FPI started walking from the organization's headquarters in Tanah Abang and wandered through the city until morning prayers , heading for various mosques.

Milad: the organization's self-celebration

Traditionally, the FPI celebrates its birthday every August with great effort ( Milad , from Arabic mīlād ). In the early years she also held large parades on this occasion. In 1999 the event was called “Great Anti-Maksiat Parade” (Pawai Akbar Anti Maksiat) , in 2000 “Jakarta Charter Parade” (Pawai Piagam Jakarta) , 2001 “Islamic Sharia Parade” (Pawai Syariat Islam) , 2002 “Parade of Islamic Law ” (Pawai Hukum Islam) and 2003“ Parade of God's Law ” (Pawai Hukum Allah) . The parades from 2000 to 2002 led from the FPI headquarters in Petamburan to the parliament building and from there back to Petamburan. The 1999, 2003 and 2004 parades took the form of motorized processions around the city. 5,000 FPI activists from various regions of Indonesia took part in the 2001 parade, in which the demand for the reinstatement of the Jakarta Charter was in the foreground.

In the years that followed, the FPI began to celebrate the anniversaries of its foundation with a Tabligh akbar. In August 2013, to celebrate the organization's 15th anniversary, a Tablig akbar was held, attended by thousands of FPI members. The street from Petamburan, in which the FPI headquarters are located, was partially closed. Then the FPI members organized a tour around Jakarta in a car parade . The third national assembly of the FPI took place on this occasion.

Humanitarian action

Leading representatives of the FPI pointed out in press interviews that their organization also pursues a humanitarian program that includes tree-planting campaigns and participation in village rehabilitation programs. The most important humanitarian action of the FPI so far has been its involvement in the devastating tsunami that struck the province of Aceh on December 26, 2004 . After this disaster, hundreds of FPI volunteers and Habib Rizieq poured into Banda Aceh within two days , with the transport organized by the government. The FPI made a name for itself mainly by recovering and burying the bodies. In total, the FPI is said to have recovered 100,000 bodies after the tsunami.

In November 2014, the Indonesian newspaper Republika reported that the FPI is participating in flood control efforts in Jakarta by carrying out reforestation work in the upper area of the Ciliwung , the river that flows through Jakarta. In January 2014, the FPI planted 40,000 trees in Puncak, where there are four inlets for the Ciliwung. Habib Rizieq Sihab plans to plant another 300,000 trees there in December. The FPI's Daʿwa Committee organized a public breaking of the fast on June 13, 2018 in Petamburan with an aid event for orphans.

Use of force

According to Munajat, the collective activities of the FPI can be divided into four different types:

- violent actions in which people or property are harmed;

- Actions in which the FPI threatens violence to people or groups of people armed with wooden sticks or other simple weapons in order to enforce claims without harming people or property;

- Actions in which the FPI only verbally threatens to use violence in order to enforce demands, for example against the government;

- other non-violent actions, e.g. submitting petitions or dialogue with authorities.

Of the 233 collective actions of the FPI between 1998 and 2010 that Munajat learned about from newspapers, 64 cases (27%) belong to category 1, 34 cases (14%) to category 2; 18 cases (8%) in category 3 and 118 cases (approx. 50%) in category 4. 40 percent of the violent activities of the FPI were associated with crackdown on immorality (Maksiat).

According to Rizieq Syihab, the FPI obliges each of its activists to learn martial arts for self-defense . In an interview with Ian Wilson, the former FPI General Secretary Ahmad Sobri Lubis once emphasized that violence is only the last resort that the FPI uses when the local authorities or the police fail to comply with their demands against violations of existing law or to proceed with the "moral order". In December 2003 Lubis announced a paradigm shift in the FPI's struggle away from mass action and militancy (kelaskaran) towards education. In the future, the FPI will take legal action to stop practices of immorality such as gambling and prostitution. The new paradigm was to be adopted at the First National Conference of the FPI on December 19-23, 2003 in Jakarta. But the FPI did not keep this promise. In the FPI statutes, which were adopted at this conference, a distinction is made between gentle Amar Ma'ruf and determined Nahi Munkar , but the latter advocates the use of force and in no way renders violent action. As early as October 2004, the FPI showed with attacks on cafes in southern Jakarta that it was not prepared to forego violence.

One of the violent actions of the FPI, which aroused a lot of outrage and criticism of the FPI in Indonesia, was its attack on activists of the "National Alliance for Freedom of Religion and Belief " ( Aliansi Kebangsaan Untuk Kebebasan Beragama dan Berkeyakinan ; AKKBB) on June 1, 2008 at Monas in Jakarta's central Merdeka Square, also known as the "Monas Incident" (Insiden Monas) . The AKKBB was an amalgamation of around 50 Indonesian religious and interreligious organizations and institutes that campaigned for freedom of religion, particularly with regard to the Ahmadiyyah. The background to the attack by the FPI was that the AKKBB had published a full-page statement in several Jakarta newspapers on May 10, 2008, in which it pointed out that the Indonesian constitution guarantees religious freedom for its citizens and criticized the groups that violate this principle. This statement angered the FPI, and on June 1, the day of the celebration of Pancasila , the Monas incident occurred: when around 1,500 members of the AKKBB, including members of the Ahmadiyyah, demonstrated for religious freedom, they became activists attacked the FPI, who were demonstrating there with other groups against the increase in fuel prices. According to the FPI, the trigger for this was that the AKKBB called them "Satan's militia" (Laskar Setan) at their rally . The FPI activists beat the protesters with bamboo sticks AKKBB one, they pelted with stones; they found Takbeer shouts out. At least 70 people from AKKBB, including women, were injured in the incident, 29 of them seriously. Among the victims of the FPI attack were the director of the International Center for Islam and Pluralism (ICIP) Syafii Anwar and the director of the Wahid Institute Ahmad Suaedy.

The FPI and the Indonesian Society

The FPI is very well known in Indonesia. A survey by the Alvara Research Center in 2017 showed that 68.8 percent of all Indonesians are familiar with the FPI. It is better known than many other Islamic organizations that were founded much earlier. The respondents mainly associate the FPI with rigidity and violence. As Rizieq Syihab himself admits, the violence orientation of the FPI is rejected by many people in Indonesia. They regard this as "violence under the guise of religion" (kekerasan berkedok agama) . According to a survey by the Indonesian polling institute Lembaga Survei Indonesia in 2005, only 16.9 percent agreed with the activities of the FPI. However, the population's approval of the FPI was greater than that of groups from the liberal Islamic camp. Between 2005 and 2007, an average of 17 percent of Indonesians agreed with the goals for which the FPI is fighting.

The social structure of the FPI

Rizieq Syihab points out in his FPI book that the following of his organization is very heterogeneous and includes Abangan as well as Santri . A total of four large social groups can be distinguished within the FPI:

- The first group are the Habaib (see below) and the ʿUlamā ' . They provide the members of the Consultative Council and also occupy the most important posts on the Executive Council and its subdivisions. Habib Rizieq himself regards the Kyai Kampung , the Islamic neighborhood clergy, as the most important elements in the FPI movement. Numerous Kyais are represented in the organization who have been running their own pesantren schools for a long time. At the social base, the organization also receives support from volunteer religion teachers of the Ustadz type.

- The second group are academics and students. Most of them come from technical and scientific subjects and have no religious education. They joined the FPI because they have a great passion (ghiroh) for Islam and see the FPI as the Islamic organization that most strongly defends the Muslim community. The involvement with the FPI gives them quick recognition as fighters for Islam. They typically work in departments of the organization that are not related to religion. Similarly, Jahroni names young, educated Muslims from the middle and lower classes as the second component of the organization.

- The third group are the fighters of the LPI. The FPI leadership recruits them from poor neighborhoods and especially from the ranks of petty criminals and political rioters, so-called premans . As sociological studies have shown, some of the premans did not join the FPI for ideological, but rather for socio-economic reasons: they hope that this will give them a better reputation and a better negotiating position with potential employers who particularly trust FPI supporters. A leading member of the FPI explained the special composition of the FPI militia in 2003 by saying that it had grown extremely quickly and that one could not pay attention to the quality of its recruits. Rizieq Syihab admits that among the FPI members who engage in AMNM activities there are still many who are badly behaved and have no religious knowledge. The FPI leadership makes no secret of the proletarian-populist background of its militia, because this image means that it is very feared by its opponents as the “power of the streets”. However, she sees no real problem in the criminal background of many of her fighters, because in her opinion a criminal who has performed the tauba is better than a lukewarm Muslim without a firm religious attitude.