Cliffs

The word Klinterklater or Klinter-Klater is a term used in the city of Braunschweig and its immediate surroundings that originated in the 19th century. It gradually disappeared due to the dramatic demographic changes in the city after the end of World War II , but has been used more and more in recent years - and after a change in meaning. Contrary to its original meaning of the term is understood today and positive means persons "with Okerwasser baptized" (slogan: "Brunswiker Klinterklater are baptized with Okerwater") were so born in Braunschweig.

Origin and original meaning

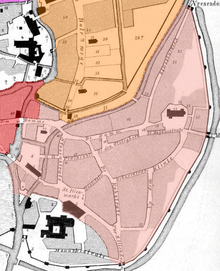

The noun "Klint" used in Brunswick , a Low German dialect , describes a hill that rises from a river valley (in the case of Braunschweig the Oker valley). Within the city walls there are four "Klinte", namely Bäckerklint , Radeklint and Südklint (in the northwestern old town ) and the Klint in the eastern Magniviertel . They are all located near the Oker and rise from its lowland.

The noun “Klater”, also in Low German, means “dirt”, “rags” or “rags”, while the adjective “klaterig” means “dirty”, “ragged”, “puny”, but also “cheeky”.

By merging “Klint” and “Klater”, a term with initially negative connotations was created , which disparagingly referred to the poorer sections of the population in the city, who lived in the “Klinte” at the end of the 19th century. The newly created word thus referred to poor and ragged-looking people and soon found general application to the city's poorer sections of the population who lived in the older, often neglected houses, for example on Echternstrasse , Küchenstrasse, Mauernstrasse, on Nickelnkulk , Weberstrasse and Werder and mainly spoke Brunswieker Platt .

Stigmatization and a change in meaning

The swearword “Klinterklater” found rapid and widespread dissemination within the city and led to the stigmatization of those named.

An old mocking poem from Braunschweig illustrates the social situation of these sections of the population:

Murenstrate, Klint and Werder,

everyone should beware of that.

Nickelnkulk isn’t sure,

because that's where the knifefinder live.

Long Strate oh no less,

because a lot of children live there!

In standard German:

Mauernstrasse, Klint and Werder,

everyone should beware of that.

Nickelnkulk is no better either,

because that's where knifers live.

Long street no less,

because a lot of children live there!

The following verse is only slightly modified from this:

Mauernstrasse, Klint and Werder,

yes, German spoilers live there.

Nickelnkulk is no better either,

because ogres live there.

On October 27, 1887, this finally culminated in the fact that the residents of the “Klint” in the Magniviertel demanded that the city of Braunschweig change the name of their street, but this was rejected.

Since Braunschweig's city center, which had largely consisted of half-timbered houses before the Second World War , was more than 90% destroyed by the numerous bombing attacks and as a result the local population permanently emigrated, "Klinterklater" fell more and more into oblivion and almost disappeared from the collective memory . It was only with the publication of two books by a Braunschweig journalist in 1993 and 1995 that the term regained new popularity and distribution and has since experienced a change in meaning: Today it is understood positively and used more jokingly to designate long-established Braunschweig residents.

literature

- Herbert Blume : Klinterklater. In: Manfred Garzmann , Wolf-Dieter Schuegraf (Hrsg.): Braunschweiger Stadtlexikon . Supplementary volume. Joh. Heinr. Meyer Verlag, Braunschweig 1996, ISBN 3-926701-30-7 , p. 79 .

- Eckhard Schimpf : Klinterklater I - Typically Brunswick. 750 phrases, expressions and little stories. Braunschweiger Zeitungsverlag, Braunschweig 1993

- Eckhard Schimpf: Klinterklater II - Typically Brunswick. 850 phrases, expressions and little stories. Braunschweiger Zeitungsverlag, Braunschweig 1995.

- Eckhard Schimpf: What is a Vigelienenstrieker? About the language of the Klinterklater. In: Braunschweiger Zeitung . November 4, 2002 (fee required , newsclick.de ).

- Eckhard Schimpf: Klinterklater - Typically Brunswick. a thousand idioms, expressions and little stories. Klartext, Essen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8375-0034-9 .

Records

- Braunschweiger Klinterklater. A selection of short stories about Braunschweig originals and Klinterklater, retold by Gertrud Kirry. Archiv-Verlag, Braunschweig, undated (approx. 1975)

- Gertrud Kirry: The Ölper national anthem and other Braunschweiger Döneken. Archiv-Verlag (ed.), Braunschweig, undated (approx. 1977)

Web links

- Klinterklater In: The Low German Dictionary at NDR

- The Klinterklater - a dictionary

Individual evidence

- ^ Heinrich Meier : The street names of the city of Braunschweig. In: Sources and research on Brunswick history. Volume 1, Wolfenbüttel 1904, p. 14.

- ↑ Klint, glint , m . In: Jacob Grimm , Wilhelm Grimm (Hrsg.): German dictionary . tape 11 : K - (V). S. Hirzel, Leipzig 1873, Sp. 1199–1200 ( woerterbuchnetz.de - "more often than street name, like the Bäckerklint in Braunschweig").

- ↑ a b Eckhard Schimpf: Klinterklater I - Typically Brunswick. 750 phrases, expressions and little stories, Braunschweiger Zeitungsverlag, Braunschweig 1993, p. 69.

- ↑ Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 8.