Country house in Rueil

|

| Country house in Rueil |

|---|

| Édouard Manet , 1882 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 71.5 x 92.3 cm |

| National Gallery, Berlin |

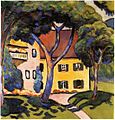

Country house in Rueil ( French La maison du Rueil ) is the title of two paintings by the French painter Édouard Manet from 1882 . The pictures show the summer garden view of a house in the Paris suburb of Rueil , where the artist stayed for a cure a few months before his death. The compositions of the works are based on Japanese models and their execution shows typical characteristics of impressionism . The two almost identical versions are painted in oil on canvas and differ mainly in their format. The landscape format motif with dimensions 71.5 × 92.3 cm is in the collection of the National Gallery in Berlin , while the portrait format version with dimensions 92.8 × 73.5 cm belongs to the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne . At the beginning of the 20th century, the views of the country house in Rueil influenced various German painters who created similar motifs based on Manet's model.

Picture descriptions

|

| Country house in Rueil |

|---|

| Édouard Manet , 1882 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 92.8 × 73.5 cm |

| National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne |

It is not known which of the two versions of the picture Manet painted first. The authors of the 1975 catalog raisonné , Denis Rouart and Daniel Wildenstein , refer to the portrait version of the Melbourne Museum as "Réplique" ( repetition ). Accordingly, Manet would have initially executed the Berlin version in landscape format. While the painting in the Berlin National Gallery is unmarked, Manet signed the version kept in Melbourne with “Manet” and dated it “1882”, a sign that he considered this execution to be complete.

Both versions of the painting show the sunlit facade of a house with a garden in front of it. The gaze is directed towards the country house; it appears parallel to the image and closes off the garden space. The wall of the house is structured by a surrounding gray cornice and a red strip of color underneath, which optically separate the two floors. In the middle of the squared pale yellow facade is the door, which is framed by a small portal with a gable top. The left white-gray column of the portal casts a shadow on the brickwork of the house wall. Its cuboids were apparently "partly drawn with a ruler," as the art historian Gotthard Jedlicka noted. Other areas of the wall, however, are done with loose brushstrokes.

There are a number of windows on both floors. In the Berlin version, the gray-blue shutters are partly open and partly closed, in the version in Melbourne all the shutters are open. The windows protruding into the dark rooms of the house “give an idea of the shady rooms”, as the author Peter Krieger points out. According to Krieger, the open windows suggest a “summery atmosphere” and “give the picture a restrained liveliness despite the empty people”. Gotthard Jedlicka argues similarly, seeing in the open windows a reference to “the occupancy of the house, the work of the housewife, the maidservant or the servant in his various rooms”.

In the Berlin version, only part of the dark blue roof can be seen, the rest is cut off from the upper edge of the picture. A lighter shade of blue in the upper left corner could suggest the sky. The author Angelika Wesenberg , however, stated: “We see little of the roof of the house, nothing of the sky”. In the National Gallery of Victoria version, the picture ends on the second floor; the roof area is completely cut off from the upper edge of the picture. Overall, the version from Melbourne shows a narrower image section compared to the Berlin version. This becomes particularly clear on the left side of the picture, where the Berlin version shows further windows. A light blue garden bench positioned in front of the house wall in the Berlin picture is also missing in portrait format from Melbourne.

In both versions, the foreground is reserved for depicting the garden. In the middle, the trunk of a tree protrudes from a lawn, which largely covers the front door. The top of the tree is only partially visible, the rest is cut from the upper edge of the picture. The traditions of Manet's godchild, Léon Leenhoff , indicate that the tree was an acacia . A path runs around this tree on the right in an arc from the lower edge of the picture to the house entrance. The curved path lies in the shadow area of the treetop and appears in a purple color with occasional lighter spots. The lush green foliage of a tree that cannot be recognized any further appears on the right edge of the picture, while individual tree branches protrude into the picture from the left. In the foreground, a lawn unfolds, the grass growth of which has been staged in a variety of ways with virtuoso brushwork. Bushes and red-blooming flower beds on the edge of the lawn complete the garden arrangement. The author Ingeborg Becker emphasizes the "spontaneously set color tones of the vegetation".

Despite the largely spontaneous painting, the two painting versions follow a composition thought out by Manet. In doing so, he was sure to orientate himself on Japanese woodblock prints, from which he took over the "unusual two-dimensionality and unmistakable detail". A central tree, for example, which cuts through the background and at the same time itself is cut from the upper edge of the picture, is not an invention of Manet, but rather borrowed from Japanese models. An example of this is the view of the Mishima Pass in the Kai Province by Katsushika Hokusai from around 1830 . Manet had known the motif from the series of 36 Views of Mount Fuji and similar works at least since the World Exhibition of 1867 and from the offerings of Parisian dealers specializing in Asian art.

The tree trunk in Manet's views of the country house in Rueil can also be seen as a vertical line of crosshairs, the horizontal equivalent of which forms the cornice and the red ribbon of the facade. Vertical and horizontal lines can also be found in the brick walls and shutters. This compositionally ordered system contrasts with a balanced interplay of the colors yellow, green, blue and red. Hugo von Tschudi emphasized "the different colors of the foreground that play from yellow to bluish". He also attested to Manet: “The wide, lively brushwork reveals astonishing security in his hand.” Françoise Cachin added, referring to the country house in Rueil , Manet's “brushwork is free and vibrant”. For Gotthard Jedlicka the country house in Rueil is "rendered with an indescribable spiritual enchantment and artistic superiority." In comparing the two picture versions, the art critic Karl Scheffler noted the version in Melbourne today that it was "perhaps even fresher, heartier and more jubilant". Hugo von Tschudi justified the inclusion of the landscape format in the collection of the Nationalgalerie in Berlin with the quality of the painting. It is a "picture from the master's last days that already appears completely classic thanks to the clarified maturity of the perception, the safe technique, the beauty of the painting."

Manet's stay in Rueil

Édouard Manet suffered from the effects of syphilis since the late 1870s . Most of all, he had severe pain in his legs, which made walking and standing difficult. From that time on, Manet spent the summer months in various Parisian suburbs to alleviate his symptoms. In 1879 and 1880 he stayed in Bellevue for spa stays and lived in Versailles for the summer of 1881 . In 1882, already marked by advanced disease, he chose the suburb of Rueil as a place of retreat. For the period from July to October, he rented the house at 18 Rue du Château for himself and his family. Various authors have assumed that the owner of the house was the comedy poet Eugène Labiche , whose name was also on Manet's list of condolences. In fact, however, the house belonged to André Labiche, as can be seen from a received letter to Manet. André Labiche may have been a relative of the author Eugène Labiche.

Manet, who was born in Paris, had repeatedly spent holidays by the sea with his family in previous years, but he was hardly enthusiastic about country life. In 1880 he wrote to his friend Zacharie Astruc from Bellevue : “The country has charm for those who are not forced to stay there.” In Rueil, Manet was already severely restricted in his freedom of movement and, in addition to painting some small-format still lifes with flowers or fruits a series of eight views in the garden of the country house. This series from the summer of 1882 includes the motifs garden corner (private collection), garden corner in Rueil (private collection), bench under trees (private collection), three versions of the garden avenue motif in Rueil ( Kunstmuseum Bern , Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dijon and private collection) and the two views of the country house in Rueil, which are in the National Galleries in Berlin and Melbourne. The art historian Ina Conzen pointed out that Manet was not interested in depicting the same motif in different light, day or weather conditions, as was done by Claude Monet . Instead, Manet only varied between portrait and landscape format for the Landhaus in Rueil .

The garden pictures from Rueil are among the few paintings by the artist that were created outdoors. The art historian Françoise Cachin suspected that the three views of the garden avenue were possibly preparatory sketches for the pictures of the country house motifs. The country house can also be seen in the row of the motif Gartenallee in Rueil , but it is shown from a distance and is largely covered by dense foliage. While in the garden pictures made in Bellevue two years earlier, people still appear sporadically, the garden pictures from Rueil are all deserted. In Rueil, the garden became the painter's last encounter with nature, as art historian Ronald Pickvance noted. For the museum director Gerhard Finckh , the views of the country house “capture the sunshine and happiness of a last summer in its very own, unsentimental way”. For Gotthard Jedlicka, Manet's last works are “wonderful pictures, and sometimes the viewer has the impression that he is unconsciously saying goodbye to this life with everyone.” In 1883, the author La Fare regretted that Manet, who had recently passed away, did not appear in the annual Exhibition of the Salon de Paris was represented. In his obituary for the painter, he was able to imagine “un charming paysage encadrant une maisonnette de Rueil” ( a charming landscape that frames a small house in Rueil ) as Manet's contribution.

Reception by German painters

Manet's country house in Rueil with the tree trimmed from the edge in the center of the picture had no noticeable aftereffects on the painter colleagues who were active in Paris. Although similar tree motifs later appeared in the work of Claude Monet and Vincent van Gogh , the artists - like Manet before them - based themselves on Japanese models.

Manet's country house in Rueil had been known to art-loving circles in Berlin since around 1900, and in 1902 the painting was depicted in landscape format in the first German-language Manet biography written by Hugo von Tschudi. Manet's motif of the country house in Rueil exerted a more or less direct influence on various German painters in the first two decades of the 20th century. A well-known example of this is Max Liebermann, who particularly valued Manet and who had brought together a number of his paintings in his collection . In Liebermann's 1901 country house in Hilversum (National Gallery, Berlin), the motif is very similar to Manet's country house in Rueil . In his picture painted in the Netherlands, Liebermann shows a bright house in a park with a lawn and a flowerbed in front of it. Like Manet, Liebermann also took up a tree trunk cut from the upper edge of the picture as a new type of picture detail. The art historian Josef Kern pointed out that there are only similarities between Manet's and Liebermann's country house paintings when it comes to the motif, whereas the choice of color and brushstroke differ significantly from one another. In 1914, Liebermann's biographer Erich Hancke spoke of the “ennobling influence of Manet's painterly delicacy” with reference to the country house in Hilversum . In 1910, Liebermann moved into his own country house on the Wannsee in Berlin , which he repeatedly chose as a motif in the years that followed, along with the surrounding garden. In significantly lighter colors and with the lively brushwork of Impressionism, Liebermann created several pictures at Wannsee, which also show trees cut from the edge of the picture against the backdrop of a country house. In the view of Birkenallee in the Wannseegarten ( Hamburger Kunsthalle ) painted in 1918 , it is a whole row of birches that takes on this element.

Other painters who referred to Manet's country house in Rueil were Max Slevogt and August Macke . Slevogt had seen the art collection of Jean-Baptiste Faure in Paris in 1899 , which contained numerous major works by Manet. He praised the works he saw as “wonderful Manets”. In his painting Garten in Neu-Kladow (National Gallery, Berlin) from 1912, Manet's familiar image components house and garden with a cut tree can be found. August Macke was also an avid fan of Manetsch painting. Mackes Staudacher Haus am Tegernsee ( Art Museum Mülheim an der Ruhr ) from 1910 also shows the country house motif known from Manet, but the painting style is already clearly located in Expressionism .

Provenance

The landscape version was in his estate after Manet's death and was shown in the memorial exhibition dedicated to him in Paris in 1884. The painter's widow, Suzanne Manet , later sold the picture to the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel . The painting then came to Berlin, where, like the same motif, it was shown in portrait format in Paul Cassirer's art salon . Cassirer also exhibited the landscape format in 1903 at the Berlin Secession . In the same year Hugo von Tschudi , director of the Berlin National Gallery, tried to secure a similar Manet country house motif for his museum. The Berlin entrepreneur Eduard Arnhold had already provided the majority of the funds for the purchase of the painting Im Garten von Bellevue ( Foundation EG Bührle Collection , Zurich) . However, in 1904 he decided to add the Bellevue view to his own collection. Tschudi was instead able to secure the country house in Rueil in landscape format at Cassirer for his museum in 1905 . The Berlin banker Carl Hagen provided the funds amounting to 50,000 marks . The painting has been part of the Nationalgalerie in Berlin since 1906.

The landscape format initially hung in the main building of the Nationalgalerie on Museum Island , before it was exhibited in the New Department of the Nationalgalerie Berlin in the Kronprinzenpalais in 1919 . After the holdings of the Nationalgalerie were relocated during World War II, the country house in Rueil was one of the works that came to the western part of Berlin after the end of the war. There the picture was first shown in the orangery of Charlottenburg Palace and from 1968 in the Neue Nationalgalerie in the Kulturforum . After German reunification and the merging of the separate museum holdings in East and West, the painting was returned to the building of the Alte Nationalgalerie.

Manet sold the portrait version of the painting on January 1, 1883 to the singer Jean-Baptiste Faure , who owned numerous works by Manet. He paid a total of 11,000 francs for the country house in Rueil, along with two other pictures . The picture came to Paul Cassirer's Berlin art salon via the Parisian art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. The latter sold the painting on October 7, 1906 for 60,000 francs to the Hamburg collector Theodor Behrens , who owned it until his death in 1921. Behrens owned several works by Manet, including the painting Nana , which today belongs to the collection of the Hamburger Kunsthalle. In 1922 his widow, Esther Behrens, sold the painting Landhaus in Rueil to the Parisian gallery Barbazanges through the art dealer Alfred Gold . From there it went to the Paris branch of the art dealer M Knoedler & Co in 1923 and to their New York house in 1924. In 1925 the painting was exhibited again in Knoedler's Paris branch and then became the property of the New York art dealer Richard Dudensing and Son . The dealer Valentine Dudensing returned the picture to Galerie Knoedler in November 1925. The latter sold the painting through its London branch in 1926 for £ 4,500 to the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, which acquired the painting with funds from the Felton Bequest purchase budget .

literature

- Scott Allen, Emily A. Beeny, Gloria Groom: Manet and modern beauty, the artist's last years . Exhibition catalog Art Institute of Chicago and J. Paul Getty Museum Los Angeles 2019–2020, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 2019, ISBN 978-1-60606-604-1 .

- Ingeborg Becker: French painting from Watteau to Renoir . Herzog-Anton-Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig 1983, ISBN 3-922279-03-1 .

- Françoise Cachin , Charles S. Moffett and Juliet Wilson-Bareau : Manet: 1832–1883 . Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, German edition: Frölich and Kaufmann, Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-88725-092-3 .

- Ina Conzen: Edouard Manet and the Impressionists . Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit 2002, ISBN 3-7757-1201-1 .

- Sonia Dean: European paintings of the 19th and early 20th centuries in the National Gallery of Victoria . National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne 1995, ISBN 0-7241-0179-9 .

- Gerhard Finckh (ed.): Edouard Manet . Von der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal 2017, ISBN 3-89202-098-1 .

- Erich Hancke: Max Liebermann. His life and works . Cassirer, Berlin 1914.

- Johann Georg Prinz von Hohenzollern , Peter-Klaus Schuster (ed.): Manet to van Gogh, Hugo von Tschudi and the struggle for modernity. Nationalgalerie Berlin and Neue Pinakothek Munich 1996, ISBN 3-7913-1748-2 .

- Gotthard Jedlicka : Edouard Manet . Eugen Rentsch Verlag, Erlenbach-Zurich 1941.

- Josef Kern : Impressionism in Wilhelmine Germany, studies on the art and cultural history of the Empire . Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 1989, ISBN 3-88479-434-5 .

- Peter Krieger : Impressionist painter from the National Gallery . Mann, Berlin 1967.

- Ulrich Luckhardt, Uwe M. Schneede : Private Treasures, about collecting art in Hamburg until 1933 . Christians, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-7672-1383-4 .

- Édouard Manet: Letters . German translation by Hans Graber, Benno Schwabe Verlag, Basel 1933.

- Tobias G. Natter , Julius H. Schoeps (Eds.): Max Liebermann and the French Impressionists . DuMont, Cologne 1997, ISBN 3-7701-4294-2 .

- Ronald Pickvance : Manet . Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny 1996, ISBN 2-88443-037-7 .

- Denis Rouart, Daniel Wildenstein : Edouard Manet: Catalog raisonné . Bibliothèque des Arts, Paris and Lausanne 1975.

- Karl Scheffler : Fifty (sic) years of French painting, 1875–1925, exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris . In Art and Artists Volume 24, Book I.

- Adolphe Tabarant : Manet et ses Œuvres . Gallimard, Paris 1947.

- Hugo von Tschudi : Manet . Cassirer, Berlin 1902.

- Angelika Wesenberg (Ed.): National Gallery Berlin, the XIX. Century, catalog of the works exhibited . Seemann, Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-363-00765-5 .

- Angelika Wesenberg (Hrsg.), Birgit Verwiebe (Hrsg.), Regina Freyberger (Hrsg.): Painting in the 19th Century, the National Gallery Collection , Volume 2. L – Z, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin and Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg 2017 , ISBN 978-3-88609-788-3 .

Web links

- Information on the painting in the National Gallery Berlin

- Information about the painting in the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ German image title according to Angelika Wesenberg: Landhaus in Rueil in Angelika Wesenberg (Ed.), Birgit Verwiebe (Ed.), Regina Freyberger (Ed.): Malkunst im 19. Jahrhundert, the collection of the Nationalgalerie , 2017, volume 2. L– Z, page 552.

- ^ French image titles according to Denis Rouart, Daniel Wildenstein: Edouard Manet: Catalog raisonné , p. 296.

- ↑ Size information according to Angelika Wesenberg: Landhaus in Rueil in Angelika Wesenberg (Hrsg.), Birgit Verwiebe (Hrsg.), Regina Freyberger (Hrsg.): Malkunst im 19. Jahrhundert, the collection of the Nationalgalerie , 2017, Volume 2. L – Z , Page 552.

- ↑ The sizes can be found on the website of the National Gallery of Victoria .

- ↑ The two paintings with the title La maison du Rueil bear the number 406 (version in the Museum of Melbourne) and number 407 (version in the Berlin National Gallery) in the catalog of the catalog raisonné from 1975. At number 406 is noted “Réplique en hauteur du no 407”, see Denis Rouart, Daniel Wildenstein: Edouard Manet: Catalog raisonné , p. 296.

- ^ Scott allen: The House at Rueil in Scott Allen, Emily A. Beeny, Gloria Groom: Manet and modern beauty, the artist's last years . P. 315.

- ^ Scott Allen, Emily A. Beeny, Gloria Groom: Manet and modern beauty, the artist's last years , p. 315.

- ↑ Gotthard Jedlicka: Edouard Manet , p. 383.

- ↑ Peter Krieger: Painter of Impressionism from the National Gallery , p. 18.

- ↑ Peter Krieger: Painter of Impressionism from the National Gallery , p. 18.

- ↑ Gotthard Jedlicka: Edouard Manet , p. 383.

- ↑ Angelika Wesenberg: Country house in Rueil in Angelika Wesenberg, Birgit Verwiebe, Regina Freyberger: Painting art in the 19th century, the collection of the National Gallery , p. 552.

- ^ Léon Leenhoff quoted in Françoise Cachin: Landhaus in Rueil in Françoise Cachin, Charles S. Moffett and Juliet Wilson-Bareau: Manet: 1832–1883 , p. 495.

- ↑ Peter Krieger: Painter of Impressionism from the National Gallery , p. 18.

- ^ Ingeborg Becker: French painting from Watteau to Renoir , p. 135.

- ↑ Angelika Wesenberg: Landhaus in Rueil in Angelika Wesenberg, Birgit Verwiebe, Regina Freyberger: Painting in the 19th century, the collection of the National Gallery , Volume 2, p. 552.

- ↑ Gotthard Jedlicka: Edouard Manet , p. 383.

- ↑ Peter Krieger: Painter of Impressionism from the National Gallery , p. 18.

- ↑ Angelika Wesenberg: Country house in Rueil in Angelika Wesenberg, Birgit Verwiebe, Regina Freyberger: Painting art in the 19th century, the collection of the National Gallery , p. 552.

- ^ Hugo von Tschudi: Manet , p. 24.

- ^ Françoise Cachin: Country house in Rueil in Françoise Cachin, Charles S. Moffett and Juliet Wilson-Bareau: Manet: 1832–1883 , p. 496.

- ↑ Gotthard Jedlicka: Edouard Manet , p. 382.

- ↑ Karl Scheffler: Fifty (sic) years French painting, from 1875 to 1925, exhibition at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris . In Art and Artists Volume 24, Book I, p. 26.

- ↑ Hugo von Tschudi quote from Angelika Wesenberg: Edouard Manet, Landhaus in Rueil in Johann Georg Prinz von Hohenzollern, Peter-Klaus Schuster: Manet bis van Gogh, Hugo von Tschudi and the struggle for modernity p. 84.

- ↑ Josef Kern: Impressionism in Wilhelminian Germany , p. 175.

- ^ Françoise Cachin, Charles S. Moffett and Juliet Wilson-Bareau: Manet: 1832-1883 , pp. 516-517.

- ^ Françoise Cachin, Charles S. Moffett and Juliet Wilson-Bareau: Manet: 1832-1883 , p. 517.

- ^ Adolphe Tabarant: Manet et ses Œuvres , p. 450.

- ^ Ronald Pickvance: Manet , p. 246.

- ↑ The name Eugène Labiche as the owner of the house in Rueil was first mentioned by the author La Fare, who wrote an obituary in the newspaper Le Gauloises on May 1, 1883 under the title Les derniers moments de E. Manet , online at BnF Gallica . The name Eugène Labiche can also be found in the 1975 catalog raisonné of Rouart / Wildenstein, see Denis Rouart, Daniel Wildenstein: Edouard Manet: Catalog raisonné , p. 23. The National Gallery in Berlin also names Eugène Labiche as the house owner in its catalog, see Angelika Wesenberg , Birgit Verwiebe, Regina Freyberger: Painting in the 19th Century, the National Gallery Collection , Volume 2, p. 552.

- ^ Françoise Cachin: Country house in Rueil in Françoise Cachin, Charles S. Moffett and Juliet Wilson-Bareau: Manet: 1832–1883 , p. 495.

- ↑ The letter is noted in Adolphe Tabarant: Manet , 1931, p. 450. André Labiche is also mentioned in Françoise Cachin: Country house in Rueil in Françoise Cachin, Charles S. Moffett and Juliet Wilson-Bareau: Manet: 1832–1883 , p 495 and Ronald Pickvance: Manet , p. 246.

- ^ Françoise Cachin: Country house in Rueil in Françoise Cachin, Charles S. Moffett and Juliet Wilson-Bareau: Manet: 1832–1883 , p. 495.

- ^ Letter of June 5, 1880 to Zacharie Astruc, German translation in Édouard Manet: Briefe , p. 94.

- ^ Denis Rouart, Daniel Wildenstein: Edouard Manet: Catalog raisonné , pp. 292-297.

- ↑ Ina Conzen: Edouard Manet and the Impressionists , p. 153.

- ↑ Peter Krieger: Painter of Impressionism from the National Gallery , p. 18.

- ^ Françoise Cachin: Country house in Rueil in Françoise Cachin, Charles S. Moffett and Juliet Wilson-Bareau: Manet: 1832–1883 , p. 496.

- ^ Françoise Cachin: Country house in Rueil in Françoise Cachin, Charles S. Moffett and Juliet Wilson-Bareau: Manet: 1832–1883 , p. 496.

- ↑ Ronald Pickvance: "The garden has become the painter's soliloquy with nature" in Ronald Pickvance: Manet , p. 246.

- ^ Gerhard Finckh: Edouard Manet , p. 293.

- ↑ Gotthard Jedlicka: Edouard Manet , p. 382.

- ^ La Fare: Les derniers moments de E. Manet , article on the front page of the Le Gauloises newspaper , May 1, 1883.

- ↑ Angelika Wesenberg: Country house in Rueil in Angelika Wesenberg, Birgit Verwiebe, Regina Freyberger: Painting art in the 19th century, the collection of the National Gallery , p. 552.

- ↑ Angelika Wesenberg: National Gallery Berlin, the XIX. Century, Catalog of the Exhibited Works , p. 240.

- ^ Hugo von Tschudi: Manet , p. 57.

- ↑ On the Liebermann Collection, see, for example, Tobias G. Natter, Julius Schoeps: Max Liebermann and the French Impressionists , pp. 197–253.

- ↑ Josef Kern: Impressionism in Wilhelmine Germany, Studies on the Art and Cultural History of the Empire , p. 59.

- ↑ Erich Hancke: Max Liebermann. His life and works , Berlin 1914, p. 402.

- ↑ Angelika Wesenberg: National Gallery Berlin, the XIX. Century, Catalog of the Exhibited Works , p. 240.

- ↑ Josef Kern: Impressionism in Wilhelmine Germany, Studies on the Art and Cultural History of the Empire , p. 59.

- ↑ Josef Kern: Impressionism in Wilhelmine Germany, Studies on the Art and Cultural History of the Empire , p. 71.

- ↑ Josef Kern: Impressionism in Wilhelmine Germany, Studies on the Art and Cultural History of the Empire , p. 180.

- ↑ Ulrich Luckhardt, Uwe M. Schneede: Private Treasures, about collecting art in Hamburg until 1933 , p. 42.