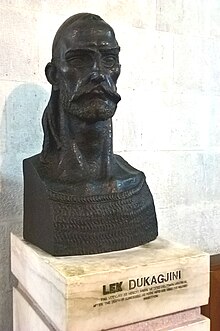

Lekë Dukagjini

Lekë III. Dukagjini (* approx. 1410 ; † after June 15, 1481 ; also: Lek, German Alexander ) was a member of the Dukagjini clan and a contemporary of Skanderbeg . Lekë fought for and against Venice , for and against the Ottomans , for and against Skanderbeg. From 1464 he fought alongside Skanderbeg against the Ottomans. The presumably wrong tradition sees in him the author of the Kanun des Lekë Dukagjini , in which the traditional customary law of northern Albania was collected.

Life

About the lineage and life of Lekë III. Dukagjini hardly has any reliable information. He is said to have been born in Lipjan (Kosovo). He was the son of Pal II. Dukagjini († 1446) and the brother of Nikollë II. , Progon III. and Gjergj IV.

The main representatives of the Dukagjini tribe in the 15th century were Pal II with his sons Lekë III. and Nikollë II. On March 2, 1444, Pal II. Dukagjini and his son Nikollë II. participated as vassals of Lekë Zaharia , the lord of Sati and Dagnum , in Skanderbeg's meeting of Lezha . Lekë III. apologized for not being able to attend the meeting. After the death of Pal II (1446) Lekë took over the leadership of the Dukagjini and the small principality of Dukagjini .

Lekë's sphere of influence was limited to a narrow strip of land in the northern Mirdita , to the valley of the Drins with the places Puka , Lura and Luma as well as the region of Polatum northeast of Shkodra . The southwest of the Albanian Alps is still called Dukagjin today. To the east of Lekë's sphere of influence was Kosovo , which had already become Turkish . With his brother Nikollë he took part in the Albanian-Venetian War (1447–1448).

In January 1445 all Albanian tribal skins were invited to the wedding of Skanderbeg's youngest sister, Mamica, with Karl Muzaka Thopia. Also present was Irene, the only daughter of Lekë Dushmani , master of the Zadrima . During carouse that followed the ceremony, began Lekë Dukagjini and Lekë Zaharia, son of Koja Zaharia († before 1442), both of which had their eye on Irene Dushmani a dispute. Vrana Konti and Vladan Gjurica (Vladan Yuritza), Quartermaster General Skanderbeg, tried to separate the two, but were wounded, the former on the arm and the latter on the head. The dispute ended in what appeared to be a battle in favor of the Dukagjini clan until Lekë Zaharia stormed his rival and knocked him out with one mighty blow. Zaharia's men celebrated the victory of their leader with loud cheers, which upset the Dukagjini. Furious at the sight of their dejected leader, they drew their swords from their sheaths and immediately challenged the men of Zaharias. The battle that followed left 105 dead and 200 wounded. Both Lekë Dukagjini and Lekë Zaharia got off alive. Zaharia managed to capture Irene. The morally humiliated Lekë Dukagjini declared the blood revenge on Zaharia . Lekë Zaharia was killed in 1445 by his pronoiar Nikollë II. Dukagjini , brother of Lekë.

Turkish invasions

During the Turkish invasions of 1455-1456 Lekë III. defended as a Venetian vassal Dagnum. Because of some dubious suspicions, Lekë fell out with the Venetians and occupied Dagnum with his troops on November 4, 1456, had the Venetian "Rettore" there chased away and his wife and children were captured. Venice immediately recruited 200 mercenaries and sent them to Albania, where, in addition to the Ottoman devastation, a new internal war was taking place.

In August 1457, when an Ottoman army besieged Kruja , Venice was able to regain Dagnum. In August 1457 the Ottomans occupied all levels of Albania. Thereupon Lekë allied with the Ottomans and took Sati with their help. This alliance caused Skanderbeg to ally with Venice against Lekë.

On February 14, 1458, a peace treaty was signed in Shkodra between the representatives of Venice and the brothers Lekë III, Nikollë II, Gjergj IV and their cousin Draga († 1462; son of Nikollë I). Venice forgave the Dukagjini all past crimes and received them as friends. The Dukagjini brothers handed over the Rogamenia (a small plain around the village of Rrogam) with all its buildings and the Dagnum area to the captain of Shkodra, Benedetto Soranzo . Lekë III. also handed over the castle of Sati with its mountains, which should be destroyed and never rebuilt. In addition, no one should live in that area without the consent of Venice. In return, he was left with the rest of the land on Mount Sati, in the Zadrima, and the possessions beyond the Drin as fiefs against an annual interest of a double (double wax torch ) of 10 pounds of wax , which was to be sent to Venice. They should only have the state deliver salt. At any request from the Venetians or their representatives, the Dukagjini were to arrest the Ribelles who were in their territory and hand them over to the Venetians. Venice undertook to do the same with the Dukagjini. But Lekë was soon looking for new conflicts, because in November 1458 Venice named him and his cousin Pal III. as "renegades"; probably they had recognized the sovereignty of Sultan Mehmed II .

Since the contract of February 14, 1458 Skanderbeg was not included and Lekë did not break off relations with the Ottomans, Pope Pius II stepped in and called on the Archbishop of Bar , Lekë and his cousin Pal III. To excommunicate “ ferandæ sententiæ ” if they do not break off relations with the Ottomans within 15 days. In 1470, Venice's ally Nikollë II defeated his brother Lekë III, who was on the side of the Ottomans.

The historian Giammaria Biemme described in his biography "Istoria di Giorgio Castrioto" that Lekë III. Dukagjini had brought the news of the death of Skanderbeg (1468) to the Albanians by tearing his clothes and tearing his hair ("... quarciandosi le vesti, e svellandosi i capelli ..."). Actually, Lekë cannot be called Scanderbeg's loyal companion, as he was his enemy for a long time.

In view of the ever increasing pressure of the Ottomans on the territory of the Dukagjini, the Archbishop of Durrës, Pal Engjëlli, the two leaders Lekë III. Dukagjini and Skanderbeg reconciled in 1463. Lekë Dukagjini joined the League of Lezha and fought faithfully by his side until Skanderbeg's death (1468).

After Skanderbeg's death

After Skanderbeg's death on January 17, 1468, Lekë Dukagjini became one of the main characters in the war against the Ottomans. The Ottomans occupied almost all of Albania, sacked Shkodra, Lezha and Durrës and abducted over 8,000 people in a few weeks. " In all of Albania we only see Turks, " read a dispatch at the same time . In addition, the old tribal chiefs feuded among themselves. The brothers Nikollë II and Lekë III. chased away their brother Progan IV, who only got his inheritance back through Venice's intervention.

After the last strongholds in 1478 (Kruja) and 1479 (Shkodra) fell to the Ottomans, Lekë III sought. and his brother Nikollë II. took refuge in Italy .

Return to Albania

After the death of Sultan Mehmed II on May 3, 1481, unrest broke out in the Ottoman Empire , which prevented the dispatch of new troops for the Ottomans besieged in Otranto . Gjon II. Kastrioti was considered a bearer of hope for the Albanians who did not want to come to terms with the Ottoman rule. As the son of the great Skanderbeg, he was supposed to lead the uprising against the occupiers. Together with Gjon and his troops, his cousin Konstantin (Costantino) Muzaka and the brothers Lekë III sailed . and Nikollë II. Dukagjini on four Neapolitan galleys to Albania. Gjon went ashore south of Durrës, while Constantine sailed further south to Himara . The Ragusans reported to Naples in early June 1481 that Nikollë II had returned to Albania; on June 15 they could do the same from Lekë III. to report. The number of fighters increased rapidly by insurgents. Nikollë and Lekë Dukagjini traveled to northern Albania, where they led the uprising in the highlands of Lezha and Shkodra. The forces of Nikollë and Lekë attacked the city of Shkodra, forcing Hadım Süleyman Pasha to send more auxiliary troops to the region. Constantine carried out military actions in the coastal region of Himara, while Albanian infantry of about 7000 men gathered around Gjon Kastrioti to prevent Vlora from reaching the Ottoman garrison in Otranto again. Gjon defeated an Ottoman army of 2,000 to 3,000 men, conquered Himara on August 31, 1481 and later the Sopot Castle near Borsh . He captured Hadım Suleyman Pasha, who was sent to Naples as a victory trophy and was finally released for a ransom of 20,000 ducats . Their temporary success had an external impact on the liberation of Otranto on September 10, 1481 by Neapolitan troops. For four years Gjon was able to stay in the area between Kruja in the north and Vlora in the south. In 1484 he finally returned to Italy. The sources are silent about the dukagjini.

literature

- Various authors: I Conti albanesi Ducagini a Capodistria: Castellani di San Servolo (The Albanian Counts Ducagini in Capodistria: Castellans of San Servolo) . Heset Ahmeti, Koper 2015 (Italian, online version ).

- Skënder Anamali, Kristaq Prifti, Instituti i Historisë (Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë): Historia e Popullit Shqiptar (The History of the Albanian People) . tape 1 . Botimet Toena, Tirana 2002, p. 264 (Albanian).

- Giammaria Biemmi: Istoria di Giorgio Castrioto detto Scander-Begh . Giammaria Rizzardi, Brescia 1756 (Italian).

- Johann Samuelersch , Johann Gottfried Gruber : General encyclopedia of the sciences and arts . First Section AG. Hermann Brockhaus, Leipzig 1868 ( online version in the Google book search).

- John Van Antwerp Fine: The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century . University of Michigan Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0-472-10079-8 (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- Edwin E. Jacques: The Albanians: an ethnic history from Prehistoric Times to the Present . McFarland & Co, Jefferson, North Carolina 1995, ISBN 0-89950-932-0 (English).

- Hasan Kaleshi: Dukagjini . In: Biographical Lexicon on the History of Southeast Europe . tape 1 . Munich 1974, p. 444-446 ( ios-regensburg.de ).

- Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann Hopf : Breve Memoria de li Discendenti de nostra casa Musachi (brief reminder of the descendants of our house Musachi) . In: Chroniques gréco-romanes: inédites ou peu connues, publiées avec notes et tables généalogiques . Weidmann, Berlin 1873, p. 270–340 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- Tim Lezi: Scanderbeg, General of the Eagles . Xlibris Corporation, 2011, ISBN 978-1-4628-6276-4 (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- Noel Malcolm: Kosovo: A Short History . Macmillan, London 1998 (English).

- Lucia Gualdo Rosa, Isabella Nuovo, Domenico Defilippis: Gli umanisti e la guerra otrantina: testi dei secoli XV e XVI (The Humanists and the Otranto War: Texts from the 15th and 16th centuries) . Edizioni Dedalo, Bari 1982, ISBN 978-88-220-6005-1 (Italian, online preview in Google Book Search).

- Fan Stylian Noli: George Castrioti Scanderbeg (1405-1468) . Dissertation. Boston University, 1945 (English).

- Paolo Petta: Despoti d'Epiro e principi di Macedonia. Esuli albanesi nell'Italia del Rinascimento . Argo, Lecce 2000, ISBN 88-8234-028-7 (Italian).

- Riccardo Predelli: I libri commemoriali della Repubblica di Venezia: Regestri, Volume V . University Press, Cambridge 2012, ISBN 978-1-108-04323-6 (Italian, online preview in Google Book Search).

- Maurus Reinkoski: Customary Law in the Multinational State: The Ottomans and the Albanian Kanun . In: Legal Pluralism in the Islamic World: Customary Law between State and Society . de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 2005 ( uni-freiburg.de [PDF; 3.2 MB ]).

- Oliver Jens Schmitt: Skanderbeg, The new Alexander in the Balkans . Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-7917-2229-0 .

- Gail Warrander, Verena Knaus: Kosovo . Bradt Travel Guide, Chalfont St Peter 2007 (English, online preview in Google book search).

- Christian Zindel, Andreas Lippert, Bashkim Lahi, Machiel Kiel: Albania: An Archeology and Art Guide from the Stone Age to the 19th Century . Böhlau Verlag GmbH, Vienna 2018 ( online preview in the Google book search).

Remarks

- ↑ The Albanian-Venetian War of 1447–1448 was waged between the Venetian and Ottoman forces against the Albanians under Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg.

- ^ Title attributed to senior government officials.

Web links

- John Musachi: Brief Chronicle on the Descendants of our Musachi Dynasty, 1515. Albanianhistory.net, accessed April 8, 2020 .

- Fatos Tarifa: Of Time, Honor, and Memory: Oral Law in Albania. (PDF) Mospace.umsystem.edu, accessed on April 8, 2020 (English, in: Oral Tradition 23/1, 2008).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Hasan Kaleshi

- ↑ Noel Malcolm, p. 17

- ↑ Maurus Reinkoski, p. 129

- ↑ Karl Hopf, p. 270 ff.

- ↑ Gail Warrander, Verena Knaus, p. 141

- ↑ Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë, p. 310

- ↑ Giammaria Biemmi, p. 61

- ↑ Fatos Tarifa, pp. 3-14

- ↑ Helmut Eberhart, Karl Kaser (ed.): Albania - Tribal life between tradition and modernity . Böhlau Verlag, Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-205-98378-5 .

- ↑ Albania: An Archeology and Art Guide, p. 509

- ↑ a b c d Edwin E. Jacques, p. 176

- ^ Fan Stylian Noli, p. 124

- ^ Fan Stylian Noli, p. 125

- ↑ Tim Lezi, p. 36

- ^ Van Antwerp Fine, p. 557

- ↑ a b General Encyclopedia of Sciences and Arts, p. 135

- ↑ General Encyclopedia of Sciences and Arts, p. 134

- ↑ Paolo Petta, p. 205

- ↑ Skanderbeg - The New Alexander, p. 141

- ↑ Riccardo Predelli, p. 132

- ↑ a b Paolo Petta, p. 204

- ↑ Paolo Petta, p. 218

- ↑ Giammaria Biemme, p. 479

- ↑ General Encyclopedia of Sciences and Arts, p. 157.

- ↑ a b c Gli umanisti e la guerra otrantina, p. 97

- ↑ I Conti albanesi Ducagini a Koper, S. 24

- ↑ a b c Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë 2002, p. 473

- ↑ a b c Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë 2002, p. 474

- ↑ Historia e Skënderbeut, p. 120

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dukagjini, Lekë |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Dukagjini, Lekë III. (Full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Albanian prince |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1410 |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 1481 |