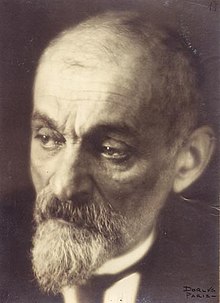

Leo Isaakowitsch Schestow

Lev Shestov ( Russian Лев Исаакович Шестов / Lew Isaakowitsch Shestov ; born January 31, jul. / 12. February 1866 greg. In Kiev ; † 20th November 1938 in Paris ; actually Yehuda body Schwarzmann ) was a Russian , Jewish philosopher of existentialism .

Life

Born in Kiev in 1866, Shestov emigrated to France in 1921 to avoid the aftermath of the Russian October Revolution . Until his death on November 20, 1938, he lived in Paris , where he taught at the Sorbonne .

Philosophy of despair

At first glance, Schestov's thoughts are anything but a philosophy: they do not form a systematic unity, a coherent system of statements, or a theoretical explanation of philosophical problems. Much of Shestov's work is fragmentary, both in terms of form (he often used aphorisms ) and in terms of style and content. Schestov often seems to contradict himself, even to seek the paradox.

This is because Shestov sees life itself as ultimately highly paradoxical. He thinks it cannot be grasped with the help of logic or reason. No theory can fathom the secrets of life. Schestov's philosophy is not "problem-solving", but rather poses problems and tries to make life appear as puzzling as possible. Schestov's philosophy is not based on an idea, but on an experience.

For Schestow, this basic experience is despair , which he describes as the loss of certainties, the loss of freedom and the loss of meaning in life. The root of this desperation is what Shestov often calls "necessity", "reason", "idealism" or "fate": a certain way of thinking, but which is at the same time a very real aspect of the world, which is ideas, abstractions and life Subjects it to generalizations and thus destroys it by failing to recognize its uniqueness and liveliness.

In the reason Shestov sees the acceptance of certainties that claim that some things are eternal and unchanging, while others are impossible and unattainable. Shestov's philosophy can therefore be seen as irrational. Schestow was not generally against reason and science, but only against rationalism and scientism . In the latter he saw the tendency to glorify reason as a kind of omniscient and omnipotent God, as an end in itself.

An individualistic trait also comes into play in Schestov's thinking : People cannot be reduced to ideas, social structures or a mystical unit.

With Schestow, people are inevitably alone in their suffering. Neither others nor philosophy can get him out of this situation.

Despair as the "penultimate word"

Despair is not the last word, but only the “penultimate”. The last word can neither be said in human language nor theoretically grasped. Schestov's philosophy is based on despair, all his thinking is desperate, and yet he tries to point to something that lies beyond despair - and philosophy.

He calls this belief . What is meant is not a belief in the sense of security, but a different way of thinking that emerges from deepest doubt and uncertainty. It is the experience that everything is possible ( Dostoevsky ), that the opposite of necessity is not chance, but possibility. That there is limitless freedom.

Shestov never claims that life has meaning, that there is “a light behind the curtain”. Nor does he contradict the saying that all fighting leads to defeat. But Shestov insists that one should continue to struggle against fate and necessity, even if success is not certain.

influence

Shestov influenced, among others, Albert Camus ( The Myth of Sisyphus ), Benjamin Fondane , Gilles Deleuze and especially Emil Cioran .

Today it is only little known and read.

Works, chronologically

- Шекспир и его критик Брандес , St. Petersburg: Stasyulevitch, 1898. 282 pp. ( Shakespeare and his critic Brandes )

- Добро в учении гр. Толстого и Ницше (философия и проповедь) , 1900, ( Tolstoy and Nietzsche . The idea of the good in their teachings , Matthes & Seitz. 1994 ISBN 3-88221-266-7 ) (EA: Marcan-Block-Verlag, 1923. 262 S.)

- Достоевский и Ницше (философия трагедии) St. Petersburg: Stasyulevitch, 1903. 245 p. ( Dostojewski and Nietzsche , Cologne, Marcan-Verlag, 1924. 389 p.)

- Апофеоз беспочвенности (опыт адогматического мышления) , St. Petersburg: Obshestvenaya Polza, 1905. 285 pp. The work was first published in 2015 in German translation: Apotheose der Grundlosen und other Schriften. Selected, translated and edited by Felix Philipp Ingold . Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-88221-391-1 ).

- Начала и Конци. Сборник статей , St. Petersburg: Stasyulevitch, 1908. 152 p. ( Penultimate words , Ed. Quatre en Samisdat, Berlin 1996, English: Anton Chekhov and Other Essays and Penultimate Words )

- Великие Кануны , St. Petersburg: Shipovnik, 1911. 314 S. ( The big eves , Eng .: Great Vigil )

- Власт ключей. Potestas Clavium , Berlin: Skythen-Verlag, 1923. 279 pp. ( Potestas Clavium or the Keys , Munich, Verlag der Nietzsche-Gesellschaft, 1926. 459 pp., Translator: Hans Ruoff )

- На Весах Иова. Странствования по душам , Paris: Annales Contemporaines, 1929. 371 p. ( Auf Hiob's Waage , Berlin: Lambert Schneider, 1929. 578 p.)

- Kierkegaard et la philosophie existential. Vox clamantis in deserto , Paris: Ed. Les Amis de Léon Chestov et Librairie philosophique J. Vrin, 1936, 384 p. ( Kierkegaard and the existential philosophy , Graz: 1949, 281 p.)

- Athènes et Jérusalem. Un essai de philosophie religieuse , Graz 1938. ( Athens and Jerusalem. An attempt at a religious philosophy Schmidt-Dengler, Graz 1938; new edition with afterword, an essay by Raimundo Panikkar : Matthes & Seitz, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-88221-268- 3 )

- Умозрение и Откровение. Религиозная философия Владимира Соловьева и другие статы , Paris: YMCA Press, 1964. 347 p. ( Speculation and revelation. Essays and critical considerations Ellermann, Hamburg 1963)

literature

- Sonja Koroliov: Lev Šestov's apotheosis of the irrational: with Nietzsche against Medusa . Peter Lang Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-55642-9 (also dissertation, University of Heidelberg 2004).

- Stephen Armstrong: Leo Shestov's Philosophy of Creative Freedom . Dissertation, University of Cologne 2005.

- Günter Schulte : Frenzied speeches. Schestow's radical critique of reason (Edition Questions; Vol. 2). Salon-Verlag, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-89770-027-1 .

- Eveline Goodman-Thau : Athens and Jerusalem under the spell of history. To Leo Schestow . In: This .: Revolt of the waters. Jewish hermeneutics between tradition and modernity . Philo-Verlag, Berlin 2002, pp. 158-172, ISBN 3-8257-0267-7 .

- Michaela Willeke: Lev Šestov. On the way from nothing through being to fullness; Russian-Jewish milestones on philosophy and religion (religion, history, society; vol. 37). Lit-Verlag, Münster 2006, 345 pages, ISBN 3-8258-9012-0 .

- Peter Ehlen , Gerd Haeffner , Friedo Ricken : Philosophy of the 20th Century (Urban Pocket Books; Vol. 354). 3rd edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, pp. 76-79, ISBN 978-3-17-020780-6 .

- Wolfdietrich von Kloeden : Schestow, Leo. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 9, Bautz, Herzberg 1995, ISBN 3-88309-058-1 , Sp. 174-176.

Web links

- Literature by and about Leo Isaakowitsch Schestow in the catalog of the German National Library

- Lev Shestov Society (English)

- The Lev Shestov page, all his books in Russian and English ( Memento from August 14, 2003 in the Internet Archive )

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schestow, Leo Isaakowitsch |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Sestov, Lev; Schestow, Leo Isaak; Schwarzmann, Jehuda Leib; Shestov, Lev; Chestov, Léon |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian philosopher and writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 12, 1866 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kiev |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 20, 1938 |

| Place of death | Paris |