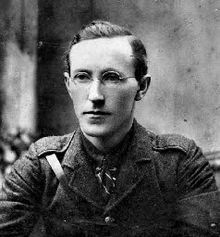

Liam Lynch (officer)

Liam Lynch ( Irish : Liam Ó Loingsigh ; * November 9, 1893 , † April 10, 1923 ) served during the Irish War of Independence as an officer in the Irish Republican Army (short: IRA; English: Irish Republican Army ) and as commanding general and Chief of Staff of the IRA's Anti-Treaty Party during the Irish Civil War .

Childhood and youth

Liam Lynch was born on the Barnagurraha Estate, County Limerick , near Mitchelstown , County Cork , to Jeremiah and Mary Kelly Lynch. After twelve years of schooling in Anglesboro, he began training in a household and hardware store in Mitchelstown in 1910, where he also joined the Gaelic League and the Ancient Order of Hibernians . He later worked in a timber trade in Fermoy . Formative impressions were the attack by the Royal Irish Constabulary on Bawnard House, the estate of the Republican Kent family in nearby Castlelyons, on May 1, 1916, when "cleaning up" after the Easter Rising , and the execution of Thomas Kent on May 9, 1916, theirs Witness he became.

The War of Independence

In 1919, Lynch in Cork reorganized the Irish Volunteers , the paramilitary group that later became the Irish Republican Army . In the guerrilla war against England he commanded the 2nd Cork Brigade of the IRA. He was soon considered to be one of the most capable commanders in the IRA. Lynch helped capture a senior British officer, General Lucas, in June 1920 and shot and killed British Colonel Danford during the events. In August 1920, Lynch, along with the other officers of the 2nd Cork Brigade, was captured during a British attack on Cork City Hall. Mayor Terence MacSwiney was among the prisoners; he died in custody as a result of a hunger strike. Lynch, on the other hand, gave a false name and was released three days later. Meanwhile, as a result of a mistake, the British had murdered two innocent men named Lynch.

In September 1920, Lynch, along with Ernie O'Malley , commanded a squad that took the British barracks in Mallow . The weapons in the barracks were confiscated and the building was partially burned down. Until the spring of 1921, Lynch and his brigade continued the guerrilla war and lured British troops into an ambush several times . a. near Millstreet . But there were also failures such as at Morne Abbey and the attack on a British troop train at Upton (Cork) on February 15, 1921, where Lynch lost 18 and 15 of his men respectively.

In April 1921 the IRA was restructured into regional divisions. Lynch's reputation was such that he was appointed commander of the 1st Southern Division (German: First Southern Division). From April 1921 until the armistice that ended the war in July 1921, Lynch's command was increasingly pressured by the increased deployment of British troops in the area and the use of small, mobile units by the British to counter IRA guerrilla tactics . Lynch was no longer in command of the 2nd Cork Brigade when he secretly had to travel to each of the nine IRA brigades in Munster . At the time of the ceasefire, the IRA under Liam Lynch was increasingly harassed and suffered from a shortage of weapons and ammunition. Lynch therefore welcomed the ceasefire as a welcome respite, but expected the war to continue once it was over.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty

The war finally ended with the signing of the Anglo-Irish treaty between the Irish negotiating team under Michael Collins and the British government in December 1921. Lynch opposed the Anglo-Irish treaty on the grounds that it proclaimed the Irish Republic in favor of one Abolish Dominion status of Ireland in the British Empire . In March 1922 he became chief of staff of the IRA, large parts of which were also against the treaty. Lynch, however, did not want a split in the republican movement and hoped to find a compromise with the supporters of the treaty ("Freistaatler") by publishing a republican constitution for the new Irish Free State . The British did not want to accept this, however, and so the Irish ranks split and ultimately the civil war .

Civil war

Although Lynch opposed the occupation of the Four Court by a group of extreme Republicans in Dublin, he joined the occupation in June 1922 when the building was attacked by the newly formed Free State Army. This marked the beginning of the Irish Civil War . Lynch was arrested by the Free State Armed Forces but was allowed to leave Dublin on condition that he tried to stop the fighting. Instead, however, he quickly began to organize the resistance elsewhere.

With the capture of Joe McKelvey at Four Courts, Liam Lynch resumed the position of chief of staff of the anti-treaty IRA forces (also called Irregulars ), which McKelvey had previously temporarily taken over. Lynch, who was most familiar with the south, planned to establish a " Munster Republic" which, in his opinion, would prevent the formation of the Free State. The "Munster Republic" would have to be defended by the " Limerick - Waterford Line". This consisted, moving from east to west, of the city of Waterford, the cities of Carrick-on-Suir , Clonmel , Fethard , Cashel , Golden and Tipperary , ending in Limerick, where Lynch had established his headquarters. In July he led its defense, but it was captured by Free State troops on July 20, 1922.

Lynch withdrew further south and set up his new headquarters at Fermoy . The "Munster Republic" fell in August 1922 when Free State troops landed by sea in Cork and Kerry . The city of Cork was captured on August 8th and Lynch abandoned Fermoy the next day. The armed forces of the contracting parties then dispersed and pursued guerrilla tactics from now on .

Lynch contributed his part to the increasing bitterness of the war by issuing the so-called orders of frightfulness on November 30, 1922 against the provisional government. This general order approved the killing of Senators and members of the Free State Parliament (TD's; Irish: Teachta Dála ), as well as certain judges and newspaper publishers, in retaliation for the Free State's killing of captured Republicans. The first Republican prisoners to be executed were four IRA men, arrested at gunpoint on November 14, 1922, followed by the execution of Republican leader Erskine Childers on November 17. Lynch then issued orders executed by IRA men that killed TD Sean Hales and wounded another TD in front of the daíl. In response, the Free State immediately shot and killed the four Republican leaders, Rory O'Connor , Liam Mellows , Dick Barret and Joe McKelvey . This sparked a spiral of atrocities on both sides, including the official execution of 77 Republicans prisoners by the Free State and the "unofficial" killing of approximately 150 other Republicans prisoners. Lynch's men, for their part, launched a joint campaign against the homes of Free State MPs. Among the terrible acts they carried out were the burning of TD James McGarry's house, resulting in the death of his seven-year-old son, and the murder of State Secretary Kevin O'Higgins ' elderly father, and the burning of his house at Stradbally in the spring of 1923.

Lynch has been criticized by some Republicans, particularly Ernie O'Malley , for failing to coordinate their war effort and for allowing the conflict to end in fruitless guerrilla warfare . Lynch started unsuccessful efforts to import mountain artillery from Germany in order to turn the fortunes of war around again. In March 1923, the army command of the IRA who rejected the treaty met in a remote valley near Aherlow. Several members of the leadership suggested ending the civil war, but Lynch opposed them. He could barely win an election to continue the war.

Lynch was shot dead on April 10, 1923 in a skirmish with Free State Forces in the Knockmealdown Mountains in County Tipperary . Many historians see his death as the actual end of the civil war, as the IRA's new chief of staff, Frank Aiken , declared a ceasefire on April 30th and on May 24th ordered the IRA volunteers to lay down their arms and return home.

On April 7, 1935, a 60-foot tall round tower monument was erected on the presumed place of Lynch's death.

Footnotes

- ^ PJ Power: The Kents And Their Fight For Freedom . In: Brian Ó Conchubhair, Peter Hart (eds.): Rebel Cork's fighting story 1916–21. Told by the men who made it . Mercier Press, Cork 2009, ISBN 978-1-85635-644-2 . Pp. 106-111.

- ^ Francis Stewart Leland Lyons: Ireland since the famine . Fontana Press, London, 10th ed. 1987. ISBN 0-00-686005-2 . Pp. 451 and 454.

- ↑ George Power: The Capture of General Lucas . In: Brian Ó Conchubhair, Peter Hart (eds.): Rebel Cork's fighting story 1916–21. Told by the men who made it . Mercier Press, Cork 2009, pp. 82-88.

- ^ Patrick Lynch: Successful raid on Mallow Barracks . In: Brian Ó Conchubhair, Peter Hart (eds.): Rebel Cork's fighting story 1916–21. Told by the men who made it . Mercier Press, Cork 2009, pp. 121-126.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lynch, Liam |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Loinsgh, Liam, et al |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Irish freedom fighter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 9, 1893 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Barnagurraha , County Limerick |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 10, 1923 |

| Place of death | Knockmealdown Mountains , County Tipperary |