Light hole

A light hole , also known as a light shaft , is a narrow shaft that is sunk down to a deeper pit in order to ventilate the pit . The term light hole does not go back, as one might assume, to the incidence of daylight into the mine , but to the fact that it provides the fresh weather necessary to burn the light . In the Bensberg ore district , the light holes were also called air holes or air shafts because of their function. Light holes in a tunnel are geteuft, also called entry well or Stoll bay .

Manufacture and dimensions

Light holes were usually sunk like normal shafts. If sufficient, only simple drill holes were made. The light holes were created either saiger or tonnage , depending on the local conditions . The excavation of the light holes was heaped up in the immediate vicinity of the respective light hole to form a small light hole heap. These small heaps still mark the underground course of the respective tunnel today. The individual light holes mostly had different dimensions. The cross-section of the light holes was relatively small. The opening of the light holes was often only 0.5 laughs wide and 0.75 to a maximum of one laugh long. The shape of the shaft disk was also quite different for the light holes. In the Mansfeld mining district, the cross-sections of the light holes were initially square, later oval-shaped light holes were also created. The joints of the light shafts were only provided with expansion if the lack of stability of the adjacent rock made it necessary. Since the light holes were sunk down to the bottom of the tunnel , the respective depth depended on the thickness of the overburden and the location in the terrain. Depending on the local conditions, the depth of the light hole was between 5.2 and more than 206 meters. The starting point of the light holes was often chosen so that they did not come directly to the tunnel, but usually only penetrated the tunnel via a small cross passage or a wing location . The length of these small connecting tunnels was a few meters. The exact starting point for the individual light holes required multiple mine-separating measurements. This measurement was difficult because the light holes were placed on the side of the tunnel.

Distances and number

The number and spacing were very irregular at the beginning of the tunnel construction . Over the years, the light holes were created more and more systematically. They were built as required and according to the excavation of the tunnel. The number of light holes created was dependent on the respective local conditions and the length of the tunnel. There were tunnels for which up to seven light holes were sufficient. A significantly larger number of light holes was required to drive other tunnels; for example, 81 light holes were created to drive the frog mill tunnel. With a larger number of light holes, it was possible to drive the tunnel more quickly by driving on the opposite side . However, the production time for the tunnel did not decrease proportionally with the number of light holes created. In addition, the need to dig several light holes, especially when driving longer tunnels, represented a not inconsiderable cost factor. For this reason, efforts were made to limit the number of light holes to the necessary amount. The distances between the individual light holes were initially between 50 and 100 laughs, depending on the local conditions. Later, when creating a new light hole, distances between the light holes of 300 to 400 laughs were also chosen. The maximum distance between two light holes was 1600 laughs.

use

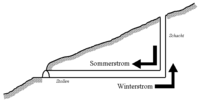

A light hole was primarily used to ventilate the tunnel . Here, the result of the natural pressure differential between was Stollenmundloch emerging and light hole opening natural Wetterzug used to bewettern to the studs. The amount of weather was then sufficient to supply the miners with fresh weather and to supply the mine lights with oxygen. In addition, various light holes were also used for dewatering and extraction. There were also light holes for Seilfahrt the miners were used. The light hole 81 / II of the frog mill tunnel was still used for driving and ventilating the tunnel until 1969 . Ultimately, in the case of longer tunnels, several light holes were often created in advance in order to drive the tunnel more quickly by driving on the opposite side.

Reuse

Light holes that were no longer used for mining operations were covered with a plate. Some of the light holes were also completely or partially filled with loose material . After the end of mining, the light holes that remained open in some mining districts were fitted with pumps in order to pump out the pit water that had accumulated in the underground cavities. The pumped-out water was then used for domestic water supply.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Carl von Scheuchenstuel : IDIOTICON of the Austrian mountain and hut language. kk court bookseller Wilhelm Braumüller, Vienna 1856.

- ↑ The early mining on the Ruhr: Lichtlöcher. (accessed June 11, 2012).

- ^ Herbert Stahl (editor), Gerhard Geurts , Herbert Ommer : Das Erbe des Erzes. Volume 2, The pits on the Gangerz deposits in the Bensberg ore district. Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-00-014668-7 .

- ^ A b Heinrich Veith: German mountain dictionary with evidence. Published by Wilhelm Gottlieb Korn, Breslau 1871.

- ↑ Albert Serlo: Guide to mining science. First volume, fourth revised and up to the most recent edition supplemented, published by Julius Springer, Berlin 1884, pp. 447–449.

- ↑ a b c Albert Serlo: Guide to mining science. First volume, published by Julius Springer, Berlin 1869.

- ↑ Rudolf Mirsch, Bernd Aberle: From the art of lifting water - about the importance of the water tunnels in the Mansfeld district. Freiberg 2007 online (accessed June 11, 2012; PDF; 795 kB).

- ↑ Explanatory dictionary of the technical terms and foreign words that occur in mining in metallurgy and in salt works and technical articulations that occur in salt works. Falkenberg'schen Buchhandlung publishing house, Burgsteinfurt 1869.

- ^ Johann Karl Gottfried Jacobson: Technologischesa dictionary or alphabetical explanation of all useful mechanical arts, manufactories, factories and craftsmen. Two parts from G to L, by Friedrich Nicolai, Berlin and Stettin 1782.

- ↑ a b c Martin Spilker: The tunnels in the Mansfeld copper mining area. ( Memento of the original from November 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed June 11, 2012).

- ↑ a b Joachim Huske: The hard coal mining in the Ruhr area from its beginnings to the year 2000. 2nd edition. Regio-Verlag Peter Voß, Werne, 2001, ISBN 3-929158-12-4 .

- ↑ Kurt Pfläging: Stein's journey through coal mining on the Ruhr. 1st edition. Geiger Verlag, Horb am Neckar 1999, ISBN 3-89570-529-2 .

- ↑ Martin Spilker: 180 years Seegen-Gottes-Stolln in the Sangerhausen district. In: Association of Mansfeld Miners and Huts People eV: Communication on May 107 , 2010, p. 2 ff. Online (accessed on June 11, 2012; PDF; 1.1 MB).

- ^ A b Walter Bischoff , Heinz Bramann, Westfälische Berggewerkschaftskasse Bochum: The small mining dictionary. 7th edition. Glückauf Verlag, Essen 1988, ISBN 3-7739-0501-7 .

- ^ Franz von Paula cabinet: The beginnings of mining science. Bey Johann Wilhelm Krüll, Ingolstadt 1793.

- ^ Carl Hartmann: Handbuch der Bergbaukunst. First volume, Verlag Bernhard Friedrich Voigt, Weimar 1844.

- ^ Johann Friedrich Lempe: Magazine of mining science. Twelfth part, Walterische Hofbuchhandlung, Dresden 1798.

- ↑ Johann Georg Krünitz: Economic and technological encyclopedia, or general system of state, town, house and agriculture, in alphabetical order. Eighth and thirtieth part, printed by Joseph Georg Traßler, Brünn 1804.

- ↑ Wilfried Ließmann: Historical mining in the Harz. 3. Edition. Springer Verlag, Berlin and Heidelberg 2010, ISBN 978-3-540-31327-4 .

- ^ Moritz Ferdinand Gätzschmann: Collection of mining expressions. 2nd, significantly increased edition. Verlag von Craz & Gerlach, Freiberg 1881.

- ^ Johann Christoph Stößel (Ed.): Mining dictionary. Chemnitz 1778.

- ↑ Mansfeld copper traces, mouth hole of the Froschmühlenstollen ( Memento of the original from August 20, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed June 11, 2011).

- ^ Günter Meier, Gerhard Jost, Angelika Dauerstedt: Security and safekeeping work on the Jakob Adolph tunnel - a water-bearing tunnel under the city of Hettstedt (Saxony Anhalt). Freiberg 2007 online (accessed June 11, 2012; PDF; 591 kB).

Web links

- Conveyor technology at the 4th light hole of the Rothschönberger Stolln (accessed on June 11, 2012)

- The grave tour between Krummenhennersdorf and Reinsberg (accessed on June 11, 2012)

- Light hole a hole for light in the tunnel? (accessed on November 16, 2019)