Mayuri vina

Mayuri vina , also Taus , bālasarasvati , is a rare long-necked lute , mainly in the north of India, with a bow , whose voluminous body ends in a peacock's head. The mainly of Sikh -Musikern in Indian and Pakistani Punjab instrument played belongs to the vinas and was probably the model for the developed in the 19th century smaller string lute esraj .

Sanskrit mayura means "Peacock", as was the Farsi - and Urdu -word toff . Sanskrit bāla stands for “child”, “youthful”; Sarasvati is the goddess of wisdom and music depicted in South India with a peacock as a mount.

origin

The first multi-string Indian stringed instruments were bow harps in Vedic times , which developed from single-stringed musical bows and which can be seen on stone reliefs until the 7th century. Then they were replaced by lute instruments and rod zithers with calabash resonators. The first written reference to bowed string instruments that were remotely counted among the vinas is contained in the Sanskrit dictionary Amarakosha (9th century or earlier) ( kona translates as "bow"). The Arabic scholar al-Farabi (around 870–950) mentions the bowed rabāb for the first time in Arabic music . From the 10th century, according to BC Deva, string instruments are depicted on some temple reliefs. However, the early illustrations listed as evidence to prove the Indian origin of the stringed instruments cannot be clearly interpreted. Oral tradition has it that the fiddle ravanahattha played in folk music in Rajasthan and Gujarat originates from ancient times and was invented by the mythical demon king Ravana .

In the 12th century and in the music theory Sangita Ratnakara , written by Sarngadeva in the 13th century , the pinaki vina with the bow ( karmuka ) is mentioned. The name goes back to the mythical bow (musical bow?) Pinaki , an attribute that made Shiva invincible. The last description of this single-string instrument dates back to 1810, when it was practically extinct. In the 11th century a saranga vina is mentioned, which must have been a popular string instrument at that time, with which Jains accompanied their religious chants. This is related to the name of the sarangi , which was played in street music from the 16th century , a forerunner of the most famous Indian string instrument that is now used in North Indian classical music . The sarangi could have originated in India or, like the sarinda, derived from similar strokes in the Persian-Central Asian Islamic area. There the Afghan form of the plucked lute rubāb developed in the 18th century , which served as a model for the Indian sarod . The deleted dilruba is likely to have originated in the Mughal period .

In addition to the lute instruments introduced by Muslims, India has a long tradition of simple, obviously very old Indian strings that are played in folk music. Such one or two-stringed fiddles are called ektara , pena , banam , kingri and in southern India kinnari . The mayuri vina can be derived, depending on the perspective, from the medieval Indian lute instruments or stick zithers of the vinas type or the string and plucking sounds that came from the north-west with the Muslims. Sikh musicians trace the origin of the mayuri vina back to Har Gobind (1595–1644), their sixth guru, who is said to have invented an instrument called the saranda . The tenth Guru Gobind Singh (1666-1708) was, like his predecessors, who saw themselves a musical tradition belonging and even as dhadi understood (religious ballad singer) from which saranda the toff developed. Later Sikhs are said to have slimmed down the unwieldy Taus to the dilruba .

The Latin name pavo , derived from German for “peacock”, leads back to ancient Greek taôs , which passed into numerous other languages and with Taus also into Urdu. Mayuri has an Indian origin via Sanskrit mayura , from which Hindi mor is derived. Pavo cristatus , the blue peacock native to South Asia , is held in high esteem in India. It is thematized in music and depicted in dance, painting and in the form of everyday objects. For Hindus it is the mount ( vahana ) of the goddess Sarasvati , the god of war Skanda and the Kaumari, who belongs to the Matrikas . In mythology he is the killer of snakes; on miniature paintings he sits near the lovers he has brought together. In a motif from the Ragamala series, in which certain ragas are illustrated, the peacock represents the absent lover the lady longs for. Such representations are typical of the painting of Rajasthan in the 17th and 18th centuries. Kalidasa already made the connection to music at the beginning of the 5th century when he spoke of peacocks on river banks listening to the soothing music of the waves. In rural regions of Odisha , the tuila- like stab zither kuranrajan with two strings made of plant fibers, a calabash resonator and a peacock's head performs a magical function in funeral rituals.

Design

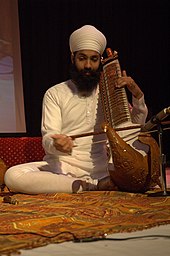

In its basic form, the mayuri vina is a larger and heavier variant of the dilruba and esraj , which belong to the same family of instruments. The bulbous resonance body is covered with a skin cover and is slightly waisted on both sides in the upper area. When viewed from above, the resonance body merges with a soft curve into the broad neck, on which four melody strings run, which are tapped on 16 to 19 metal frets. The melody strings lead from the lower end over a bridge set up in the middle of the ceiling to a pegbox that is slightly bent downwards. 16 sympathetic strings under the frets end at a row of pegs attached to the side of the neck. In the side view, the sound box is a lifelike peacock shape, with long peacock feathers usually stuck in the rear (tail) end under the neck. The white ceiling stands out from the other dark brown wooden parts. The sound box is artfully decorated with bright, shiny metal inlays.

The player sits cross-legged on the floor and holds the forward-facing instrument at an angle with his left shoulder. The bow consists of a round wooden stick covered with horse hair. The sound is gentle and deeper than that of the related string instruments.

The idea of a zoomorphic string instrument may have spread to Southeast Asia from the mayuri vina . In Myanmar, the Mon play the three-string crocodile zither mi gyaung . A similar box zither with a crocodile head is called chakhe in Thailand and takhe in Cambodia .

Style of play

The mayuri vina was and is occasionally used by Sikhs to accompany singing. Regardless of its elegant appearance, the instrument used to be in low esteem, because it was mainly associated with the Nautch dancers . These were the secular counterpart to the Devadasis , the Indian temple dancers. Nautch were beautiful girls who appeared as professional entertainers not to please the gods, but to the rulers at the courts of the Indian princely states . Their dances were accompanied by players on the tabla and on a string instrument. A famous mayuri vina player in the second half of the 19th century was Balasarasvati Jagannatha Bhatgosvami from Thanjavur . Today the mayuri vina is also used instrumentally for raga compositions played in the khyal style.

The ballet dancer Uday Shankar made Indian dance known in the West in the first half of the 20th century . When he performed with his troupe in Paris in 1931, sitar , sarod, mahuri vina and esraj were part of his exotic music ensemble.

literature

- Mayūri Veeṇā . In: Late Pandit Nikhil Ghosh (Ed.): The Oxford Encyclopaedia of the Music of India. Saṅgīt Mahābhāratī. Vol. 2 (H – O) Oxford University Press, New Delhi 2011, p. 661

Web links

- Peacock-shaped Mayuri from India. Beede Gallery, National Music Museum, University of South Dakota

- David Courtney: Mayuri Vina (aka Taus, Balasaraswati). chandrakantha.com

- Ustaad Ranbir Singh Ji playing Taus. Youtube video

- Taus Solo - Ustad Amandeep Singh Jee & Ustad Raghbir Singh Jee. Youtube video

Individual evidence

- ↑ NB Divatia: The Vina in Ancient Times. In: Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Vol. 12, No. 4, 1930-31, pp. 362-371

- ^ Henry George Farmer : A History of Arabian Music to the XIIIth Century . London 1929, p. 155 (Luzac & Company, London 1967, 1973; online at Internet Archive )

- ↑ Bigamudre Chaitanya Deva: Musical Instruments. National Book Trust, New Delhi 1977, p. 101

- ^ Joep Bor: The Voice of the Sarangi. An illustrated history of bowing in India. In: National Center for the Performing Arts, Quarterly Journal , Vol. 15 & 16, No. 3, 4 & 1, September – December 1986, March 1987, pp. 39f, 53f

- ↑ Surinder Singh: A Journey from Taus to Dilruba . ( Memento of the original from January 30, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 53 kB) Raj Academy of Asian Music

- ↑ Volker Rybatzky: Color and variety: some things about the peacock and its names in the Central Asian languages. In: Osaka University Knowledge Archive: OUKA, July 2008, pp. 187–207, here pp. 191, 197

- ↑ Krishna Lal: Peacock in Indian Art, Thought and Literature . Abhinav Publications, New Delhi 2006, pp. 32, 59

- ↑ P. Thankappan Nair: The Peacock Cult in Asia. In: Asian Folklore Studies , Vol. 33, No. 2, 1974, pp. 93-170, here p. 138

- ^ Oxford Encyclopaedia, p. 661

- ↑ Terry E. Miller, Jarernchai Chonpairot: A History of Siamese Music Reconstructed from Western Documents, 1505-1932 . In: Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies , Vol. 8, No. 2, 1994, pp. 1-192, here p. 76

- ↑ P. Sambamurthy: A Dictionary of South Indian Music and Musicians. Vol. 1 (A – F), The Indian Music Publishing House, 2nd edition, Madras 1984, p. 37 (1st edition 1954)

- ^ Joan L. Erdman: Performance as Translation: Uday Shankar in the West . In: The Drama Review: TDR, Vol. 31, No. 1, spring 1987, pp. 64-88, here p. 78