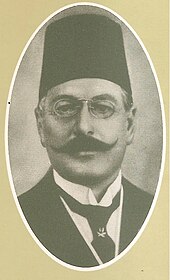

Mehmed Reşid

Mehmed Reşid Bey ( Turkish also Mehmet Reşit Şahingiray ; * February 8, 1873 , † February 6, 1919 in Istanbul ) was an Ottoman doctor and from 1909 to the end of the First World War a high local official of the Ottoman Empire . He was a co-founder of the Committee for Unity and Progress and one of those responsible for the Armenian genocide . Because of his origin he was also called Çerkez Mehmed .

Ascent

Mehmed Reşid was born on February 8, 1873 in the Caucasus . The family fled to Istanbul in 1874 . Mehmed attended the Military Medical Academy ( Mekteb-i Tıbbiye-i Askeriye ) and, together with some fellow students, was the founder of the forerunner of the Committee for Unity and Progress (KEF). In 1894 Reşid worked as Düring Pasha's assistant at the Haydarpaşa Hospital. When his links to KEF were discovered by police in 1897 , he was exiled to Tripoli . He worked there as a doctor for 10 years and married Mazlûme Hanım there.

After the Young Turkish Revolution he returned to Istanbul and worked there as a military doctor. At that time he was not yet radically anti-Christian. He wrote a pamphlet on the development of the Young Turk movement, which vigorously condemned the earlier massacres of the Armenians . The following year, on August 20, 1909, he said goodbye and began his career in the state administration, which in 1909 drew him as Kaymakam to İstanköy , later as mutasarrıf to Homs , to Trabzon , Kozan and Karesi and finally to Diyarbekir . During his tenure as District Governor of Karesi, he rigorously organized the deportation of the Greeks there , a policy supported by the Ottoman Interior Minister Talât Pascha . Over the years Reşid radicalized himself under the influence of the Balkan wars. By 1913 at the latest, he saw Christians as internal enemies. This results from his Balıkesir notları ("Notes from Balıkesir "), as Kieser writes.

Governor of Diyarbekir

His hatred, particularly directed against Armenians, manifested itself in the kidnappings and massacres of the Christian population, which he organized in the Diyarbekir province after taking office as governor on March 25, 1915 . The government had replaced the previous governor Hamid Bey , who was considered too friendly to the Armenians , with Reşid. Reşid, on the other hand, allowed himself to be convinced that the local Armenian population were conspiring against the Ottoman state , and he drew up plans for the “final solution to the Armenian question ”. During the next two months, the Armenians and Arameans in the province fell victim to a brutal campaign of extermination; they were all but wiped out in large-scale bloodbaths and deportations. According to a testimony from the Venezuelan officer and mercenary Rafael de Nogales , who visited the region in June 1915, Reşid received a three-word telegram saying “Burn-Destroy-Kill”, an order cited as official approval of his persecution of the Christian population becomes. There are several reports of the massacres in and around Diyarbakir. On July 10, 1915, the German Vice Consul in Mosul wrote to the Ambassador in Istanbul:

“ The former Mutessariff von Mardin, currently here, tells me the following: The Vali von Diarbekir, Reschid Bey, rages beneath the Christianity of his Vilajet like a mad bloodhound; He recently had seven hundred Christians (mostly Armenians) including Armenian bishops gathered in Mardin in one night by a gendarmerie specially sent from Diarbekir and slaughtered like mutton near the city. Reschid Bey continues in his blood work among innocents, whose number, as the Mutessariff assured me, exceeds two thousand today. "

Ambassador Wangenheim wrote a diplomatic note to Talât Pascha two days later. In response, Talât Pascha wrote a telegram to Mehmed Reşid in which he forbade Christians other than Armenians to be included in the "disciplinary measures" ( tedâbir-i inzibâtiye ).

In the autumn of 1915, Mehmed Reşid Talât informed Pasha in a telegram that he had deported 120,000 Armenians.

Nesimi Bey and Sabit Bey, the governors of the districts of Lice and Sabit were murdered by Resid because of their resistance to the killings by Eilbefehl. When later asked by KEF General Secretary Mithat Şükrü Bleda how, as a doctor, he had the heart to kill so many people, he replied:

“Being a doctor didn't make me forget my nationality. In this situation I thought to myself, Hey, Doctor Reschid! There are two alternatives: either the Armenians will liquidate the Turks, or the Turks will liquidate them! When faced with the need to choose, I did not hesitate long. My Turkish identity triumphed over my medical identity. The history of other peoples can write what they want about me, I don't care at all. The Armenian bandits were a lot of harmful microbes that invaded the body of the fatherland. Wasn't it the doctor's duty to kill the microbes? "

Mehmed Reşid was recalled from Diyarbakır and was Vali from Ankara from March 26, 1916 to March 27, 1917 and was then deposed because of possible corruption. He was arrested on November 5, 1918. With the help of friends, he escaped. The police tracked him down again and Mehmed Reşid shot himself on February 6, 1919. The National Assembly in Ankara granted the impoverished Reşids family a pension because of his “services to the fatherland” ( hidemât-ı vataniye ).

Mehmed Reşid's administration in Diyarbakır was unanimously condemned by contemporaries within the Ottoman Empire as the systematic extermination of Christians. After the defeat, Unionist politicians tried to portray him as an extremist who acted on his own responsibility.

See also

bibliography

- Taner Akçam : The Young Turks' Crime Against Humanity. The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire . Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ et al. 2012, ISBN 978-0-691-15333-9 .

- David Gaunt: Death's End, 1915: The General Massacres of Christians in Diarbekir. In: Richard G. Hovannisian (Ed.): Armenian Tigranakert / Diarbekir and Edessa / Urfa (= UCLA Armenian History and Culture Series. Historic Armenian Cities and Provinces. Vol. 6). Mazda Publishers, Costa Mesa CA 2006, ISBN 1-56859-153-5 , pp. 309-359.

- Hans-Lukas Kieser : From "Patriotism" to Mass Murder: Dr. Mehmed Reşid (1873-1919). In: Ronald Grigor Suny, Fatma Müge Göçek, Norman M. Naimark (Eds.): A Question of Genocide. Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press, Oxford et al. 2011, ISBN 978-0-19-539374-3 , pp. 126-148, doi: 10.1093 / acprof: osobl / 9780195393743.003.0007 .

- Maurus Reinkowski: The things of order. A comparative study of the Ottoman reform policy in the 19th century (= Southeast European works . Volume 124 ). Oldenbourg, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57859-6 , p. 67 f . (Simultaneously, Bamberg, University, habilitation paper, 2002).

- Uğur Ü. Üngör : 'A Reign of Terror'. CUP Rule in Diyarbekir Province, 1913-1923 . Amsterdam 2005 ( ermenisoykirimi.net [PDF; 1.7 MB ] University of Amsterdam, Thesis (Master)).

- Uğur Ümit Üngör: The Making of Modern Turkey. Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913–1950 . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2011, ISBN 978-0-19-960360-2 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kieser: From "Patriotism" to Mass Murder. 2011, p. 130.

- ↑ Kieser: From "Patriotism" to Mass Murder. 2011, pp. 130-133.

- ↑ Kieser: From "Patriotism" to Mass Murder. 2011, pp. 132-133.

- ↑ Hans-Lukas Kieser: Dr Mehmed Reshid (1873-1919): A Political Doctor. In: Hans-Lukas Kieser, Dominik J. Schaller (Ed.): The genocide of the Armenians and the Shoah. = The Armenian Genocide and the Shoah. Chronos, Zurich 2002, ISBN 3-0340-0561-X , pp. 245–280, here p. 258.

- ^ Üngör: The Making of Modern Turkey. 2011, pp. 63-64.

- ^ Üngör: The Making of Modern Turkey. 2011, pp. 55-106.

- ^ Rafael de Nogales : Four Years Beneath the Crescent. C. Scribner's Sons, New York NY et al. 1926, p. 147.

- ^ Üngör: The Making of Modern Turkey. 2011, pp. 72-73.

- ^ Telegram from Vice-Consul Holstein

- ↑ Original source: Başbakanlık Devlet Arşivleri Genel Müdürlüğü (Ed.): Osmanlı Belgelerinde Ermeniler. (1915-1920) (= Yayn. 14). Babakanlk Basmevi, Ankara 1994, ISBN 975-19-0818-3 , pp. 68-69, document No. 71; see. also Taner Akçam: A Shameful Act. The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility. Constable and Robinson, London 2007, ISBN 978-1-84529-552-3 , p. Xiv.

- ↑ Kieser: From "Patriotism" to Mass Murder. 2011, p. 142.

- ↑ Mely Kiyak : The missing Armenians from Diyarbakir. Zeit Online , August 9, 2013, accessed May 31, 2015 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Reşid, Mehmed |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Reşit Şahingiray, Mehmet |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Governor of Diyarbekir |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 8, 1873 |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 6, 1919 |

| Place of death | Istanbul |