Movius line

In prehistoric research, the Movius Line is a theoretical line through northeastern India that describes an archaeological limit of finding of hand axes . According to their definition, it continues north and south (see map). The line is purely phenomenological and makes no reference to its cause or the associated interpretative facets. Today it is scientifically controversial and has been replaced by newer, more complex models.

The current main problem in this context consists primarily of bringing the archaeological situation in the interpretation of the Asian tool complexes into agreement with their paleoanthropological contexts and of referring to the controversial meaning of hand axes as such and their neuroanatomical correlates.

The line, which was later named after him, was proposed for the first time in 1948 by the American archaeologist Hallam L. Movius , in order to demonstrate the technological difference between the early prehistoric toolmakers in East and West Asia, Africa and Europe based on the principle of the missing or existing hand ax industries.

Conception of the line

On the Indian subcontinent there are - widely spread - very rich finds of the hand ax industries, although the exact assignment to the potential carriers from the group of hominini is still questionable, because such Pleistocene hominini fossils are largely missing here.

In northern India, however, the situation is different. There prevailed in the early to middle Paleolithic techno complex of Soan (named after the wide valley of the Soan River in Pakistan ) against which approximately began in the Middle Pleistocene and durable rubble and discount industry represents. This can be explained as a form of adaptation to local living conditions and the availability of large quantities and different forms of rubble. From the Soan, especially of the Punjab , the industries may then have emerged, which spread to the east via rear India to China and Mongolia and to the north into the Central Asian and Russian regions.

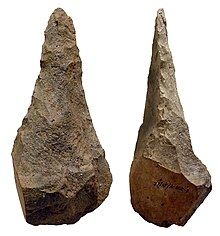

Movius had noticed relatively early on that the Paleolithic inventories of stone tools from sites in eastern and northern India never contained hand axes of the Biface type; In addition, they often consisted of formally rather less elaborate objects, which are also known as rubble devices or chopper and chopping tools . These were occasionally worked just as carefully as the devices of the Acheuléen further west, but could not be classified as real hand axes. Movius therefore drew a line on a map of India to make the difference between the tools from Europe, West Asia and Africa and those from East Asia clear.

In the late Pleistocene, too, the wedge-free and technologically rather undemanding development continued east of the Movius line. This applies to the late Soan of India as well as to the Burmese Anyathian , Malaysian Tampanian and Vietnamese Hoabinhian as well as to the Padjitanian Javas (for this special case see below). However, in the late Pleistocene industries of China, especially in the Bose Basin of southern China, bifacially machined tools of the hand ax type were occasionally found, but only for every third hand ax, the rest was machined on one side. Their age has been determined to be 800,000 years, making them the oldest accurately dated devices in East Asia. There were similar finds in Lantian (approx. 1 million BP ), from Dingcun in northern China and Chongokni (South Korea) (each around 100,000 to 200,000 BP). And in the Shui-tung-kou site (from the Ordos region ) there are devices that can even be classified as developed Levalloiso - Moustérien , and thus are characteristically Upper Paleolithic and by no means as conservative as the Chinese device inventories are occasionally classified.

Relation to human evolution

Paleoanthropological find situation

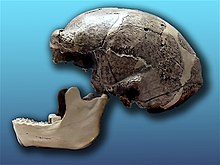

India is - as far as hominid finds are concerned - relatively poor in funds, as mentioned, and the knowledge of the spread of modern man there based on this alone is accordingly speculative; however, current (2009) genetic findings provide new clues here. Early fossil finds are also controversial about their classification. The skull roof ("Narmada Man") found in 1982 in the river bed of the Narmada near Hathnora (state of Madhya Pradesh , central India) is the only Middle Pleistocene human fossil in India. It was initially assigned to Homo erectus , but has now been assigned to the archaic Homo sapiens . Occasionally, features of the skull of Homo heidelbergensis (a precursor species of the European Neanderthals ) were discussed, since the Hathnora fossil has a mosaic character that is familiar from Africa. The dating is given today with about 600,000–400,000 years.

After all, Acheulean artifacts associated with these fossils were found. Other Indian Acheuléen sites that are assigned to Homo erectus can be found at Chirki-on-Pravara and Hungsi .

There are also problems of precise age determination with the hominid finds on Java (see below), which was connected to the Asian mainland via the Sahul shelf during the Ice Ages.

The Chinese finds, in turn, especially those from Lantian and Choukoutien , show an extremely archaic Homo-erectus pattern and, as a result of this archaism, a close relationship to the finds from Java.

Possible implications for human evolution

As far as the evolution of modern humans and their relationship to the Movius line is concerned, if one does not assume external, environmental influencing factors (e.g. material bamboo, see below), fossil evidence would have to explain the difference between the tool manufacturers on this side and beyond those established by Movius Actually support the dividing line, especially when it comes to brain capacity. If one assumes that modern man developed exclusively in Africa (so-called out-of-Africa theory ), the existence of such a dividing line must be explained in more detail, even though it predates the development of Homo sapiens lies, but theoretically would have provided the prerequisites for a later multi-regional development of modern man in Africa and Asia. In the opinion of paleoanthropologists, Movius' relatively simple conception of hominization in Asia is no longer tenable, especially when one thinks, for example, of certain very low age specifications for hominini in Java, where for the solo human (of whom one does not even know whether it is to be assigned to Homo erectus or a (pre-) Sapien type), a fossil age of 27,000 to 53,000 years was calculated, 250,000 years less than in older dates.

Problem of the special artifact find situation

A problem, however, is the fact that, for example, no artifacts were found in Java that are directly related to the Erectus forms there. In the Patjitan site (Central Java) , for example , over 150 partly very roughly worked hand axes were found in addition to chopping tools, which, however, flow over to biface types, but which cannot be classified chronologically, so that Java either isolated some here and few has developed hand ax industries or must be viewed as a transition zone, unless it is a sporadic occurrence caused by environmental influences, as is suspected for the Bose Basin in southern China (see below).

In any case, it seems easier to assume local ecological causes for this separation, for example the presence of bamboo as the starting material for tool production (see below), because the lack of suitable stone types alone cannot have been decisive, since hand axes are made from many quartzite-containing, or even not Have quartzite-containing rocks produced, which are practically ubiquitous (in Africa, for example, hand axes are almost never made from flint , but almost entirely from rock: in archeology these are basalt, diabase, diorite, gneiss, slate, jade, etc.). The only prerequisites are a halfway predictable, possibly shell-like fracture and sufficient hardness (e.g. no sandstone).

Paleoethnological Aspects

Local findings in northeast India to the west and east of the Movius Line do not lead any further here, because although the highlands of the Deccan descends here to the Ganges Delta, the oldest hand axes are there, after India was inhabited for several hundred thousand years were palaeomagnetically dated to an age of around 500,000 years - today no serious ethnic differences can be determined that could support the Movius line, even if the Adivasi are particularly common in northeast India, although their origins cannot be traced that far back. All further assumptions in this direction therefore remain highly speculative.

Theories to explain

Theories that explain the existence of the Movius line are based on different concepts.

- On the one hand, it has been suggested that people of the Homo erectus type , when they moved to Asia, knew how to make hand axes, but then passed a kind of "technological bottleneck", that is, they might have reached an area in which suitable material for the production of hand axes would have been missing (geologically rather unlikely). So the relevant skills have been forgotten. The isolation due to the enormous spatial and temporal distance from their old homeland also meant that this knowledge could not be reintroduced, unless by later immigrants of the Sapiens type, although it should be explained why their more advanced technology was then not taken over by the long-established residents, as happened in the case of the European Neanderthal man , who took over quite a few skills, including tool technology, from the modern, Upper Paleolithic Homo sapiens ( Cro-Magnon man ), who immigrated to Europe around 40,000 BP . a cultural transfer that is proven by archaeological sites in Germany and France (e.g. La Ferrassie , La Quina ).

- Another theory assumes that when Homo left Africa for the first time around 1.9 million years ago, he only mastered the tool inventory of the Olduwan , i.e. simple rubble tools such as chopping tools or choppers, which are cut off and no hand ax tools that have been worked on on both sides were. The early representatives of the hominini, especially Homo rudolfensis and Homo habilis, are considered to be the producers of these simple stone tools . The oldest Olduwan tools in Eurasia are around 1.8 million years old. They come from Dmanissi (Georgia) and were discovered in spatial connection with the earliest finds of hominine fossils outside of Africa. It was only Homo ergaster , i.e. the early Homo erectus , who then developed the techno complex of the tool tradition of the Acheuléen in Africa. The Movius line thus marks the border between the two traditions, although the hand ax tradition was only brought back with them by later immigrants. However, it was Homo ergaster , who was already producing hand axes , who left Africa for the first time and moved to Europe and Asia, so that the theory therefore has considerable chronological flaws, because the oldest African hand axes (from Ethiopia) are over 2.5 million. Years old, the next oldest from Kenya and Ethiopia about 2.3 million years, so that one has to revise the previous view that they only occurred in Africa about 1.5 million years BP, and so the premise of this theory no longer applies. The difference between these two traditions on this side and on the other side of the Movius line persisted, however, when hand ax technology was abandoned in the West in favor of Levallois technology , which does not use hammer-and-anvil technology to prepare cores like the hand ax industries, but process cuts .

- Another theory suggests that from the beginning, East Asian technology was primarily based on bamboo (and rattan ) and less on stone materials, as is still the case in some cases today. Fagan points out that the only stone tools required for this would have only had to have sharp edges, and that choppers and the chopping tools that were only sharpened on one side would have been completely sufficient. Hand axes would not have developed in the first place under these conditions. In addition, bamboo was available everywhere and, unlike certain suitable types of stone (e.g. flint), did not have to be laboriously searched for. It is hard, easy to split and easy to sharpen or sharpen. In addition, hand axes seem to have only been in use for a relatively short period of time (according to prehistoric standards) in East Asia and to have been used more as a makeshift when bamboo was not available, for example after an environmental disaster that occurred e.g. B. is occupied by numerous tektites and charcoal layers in the Bose basin (e.g. massive forest fires and destruction of the vegetation by a potential meteorite impact),

Discussion and criticism

Archeology and paleoanthropology

In addition to the paleoanthropological arguments presented above, more recent archaeological findings from Bose , China, show that there were still hand axes in East Asia. In Zhoukoudian , too , one-sided and two-sided machined fist-wedge-like devices have come to light that have been around for a million years. More recent studies therefore generally question the separation of a western hand ax and an eastern chopper circle, which is certainly strongly influenced by research history. However, this does not explain the great shortage of hand axes in East Asia, because in principle they could also have been invented locally, but were viewed as superfluous. In any case, the development of the chopper led relatively logically via intermediate steps such as pre-acheuléen with proto-hand ax to hand ax production with two-sided processing and retouching , as experimental archeology shows. Unless they were deliberately not made because there were cheaper alternatives. Because, as experimental archeology also shows, an average hand ax that is not worked too precisely but is ready-to-use can be made by an experienced worker in 20 to 30 minutes. (Certain, presumably ritually used and sometimes extremely carefully crafted specimens, which also include the grain of the stone artistically and can therefore be considered the first expression of art, certainly also took hours to produce.)

Practical considerations

It is not only in experimental archeology that the tool character of the hand ax is now sometimes even denied. Rather, it is assumed here that the hand ax was a kind of certificate of competence, which should document the manual skills of the owner, provided it was not even used ritually. Transporting a hand ax, for example when hunting or when hunters and gatherers move around, is rather cumbersome and impractical, especially when it is not in business. (You don't have one hand free, because most hand axes were too heavy - an average of one and a half pounds to 1 kg - to be tucked in a belt made of plant fiber on the hip, comfortably and stably even when running. You also need the other Hand yes for weapons such as lance or spear.) In addition, the early homo species also knew lighter and pointed, also sharp-edged, overall much more manageable and effective cuts, which could be produced in a minute if necessary and were often carried as a blank, such as mostly show the find situations at the storage areas.

A sharpening that simplifies the use of hand axes is, on the other hand, rather unlikely.This is indicated by traces of processing that suggest holding it directly in the hand, such as a small bulge to the left or right of the broad end for the ball of the thumb, which was later used in science, among other things, estimate the number of left-handed and right-handed people in the Paleolithic.

Excursus: Development of the human hand

In terms of its increasing differentiation, it is directly related to the use of tools. It is particularly noticeable in connection with hand axes that the use of such a heavy and unwieldy device, as the figure above shows, is not entirely unproblematic, especially with regard to targeting and variability, so that the long duration of hand ax technology (1st Million years) does not seem to be explainable in view of the increasing “fine adjustment” of the human hand during this period. The Vollhand- or power grip also already familiar with chimpanzees. The precision or tweezer grip , in which only two to three fingers are used (thumb, index and middle finger), also developed relatively early, because it is already being found in rudiments in chimpanzees, who manufacture up to 20 different tools and use. (The other great apes, like Homo, also have oppositional thumbs and can partially use their hands freely like us; they also do not walk on four legs, but in what is known as the ankle gait supported by the knuckles). In its present-day perfection, manual fine motor skills, on the other hand, may have developed parallel to the ability to speak and was probably only fully developed in the Upper Paleolithic in the modern sense (see functional hand ). Two anatomical factors were decisive for their development:

- An increased occupation of the finger skin ridges by tactile receptors (our ornate fingerprints were created in this way, but they already exist in great apes, even if they are far less differentiated, i.e. not as densely populated);

- a more developed control ability through the corresponding brain regions. As the Homunculus model on the right shows, voice control and hand control are closely related in the cerebral cortex. This also indicates that the development must have proceeded roughly parallel and equally weighted, since without such a coupling with a regional extent of this size, massive mutual and up to now observable competitive disturbances would have had to occur, as they would medically with serious defects in the case of one Phantom pain also occur.

Why hand axes?

In any case, the actual function of hand axes is still controversial in the scientific discussion. The suggestions range from the universal device, i.e. the “ Swiss Army Knife of the Paleolithic”, to a kind of handicraft certificate, indeed a work of art and ceremonial object, to a possible function as a certificate of competence when choosing a partner. B. in the animal kingdom with the weaver birds . Numerous specimens can be found to this day, for example in the southern Libyan Murzuk desert, which are so large and heavy that they must not have been usable for hunting - for example, in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo or in the National Museum of Tripoli. And their frequent occurrence at places of discovery rather indicates that they were mainly used at the camp site and not on the hunt, which required great mobility and quick responsiveness and where they had no meaningful and comprehensible function, the simple stones would not also fulfill (e.g. as projectiles or for breaking bones, for example at the often proven slaughtering sites), so that, as described above, they would have rather disturbed and hindered the hunter.

The bamboo technologies that still exist in South and East Asia today and require manual skills , which are completely different from those of stone processing, also did not require a corresponding symbolic certificate of proficiency in stone processing, as is assumed for hand axes . One was content with simple stone tools that fulfilled their purpose, cutting, pricking, drilling, sawing and scraping. The same phenomenon, namely a sometimes extreme simplification, even primitivation of stone tools, can also be found in Europe in the transition to the Neolithic and in its early phase, when the older devices of Paleolithic technology continued to be manufactured and used, but little effort was made on them developed related and rather new technologies such as stone grinding, stone drilling, grinding stones, sickles, etc. which required more work but were also more durable. This also made sense in the now more and more sedentary way of life. (The idea of property was only slowly emerging back then.)

Against the background of the facts presented, an essential, but practically-oriented and archaeologically experimentally proven reason for the extensive lack of hand axes east of the Movius line could be primarily that hand axes in East Asia have either been abandoned or from local variants that may appear periodically Apart from that, they were not developed to the same extent as in the classic Acheuléen west of the Movius line and thus only appeared here and there: They were simply too impractical.

Individual evidence

- ^ Movius: The Lower Paleolithic Cultures of Southern and Eastern Asia. Pp. 329 ff., 376 ff.

- ↑ Sheratt: Cambridge Encyclopedia of Archeology. P. 78.

- ↑ Kuckenburg: When man became the creator. P. 56 f.

- ↑ Sheratt: Cambridge Encyclopedia of Archeology. P. 80 f.

-

^ The HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium: Mapping Human Genetic Diversity in Asia. In: Science. Volume 325, 2009, pp. 1541–1545, doi: 10.1126 / science.1177074

A detailed graphic on the settlement routes in Asia is contained in: Dennis Normile: SNP Study Supports Southern Migration Route to Asia. In: Science. Volume 325, 2009, p. 1470, doi: 10.1126 / science.326.5959.1470 - ↑ KAR Kennedy, J. Chiment: The fossil hominid from the Narmada valley, India: Homo erectus or Homo sapiens? In: P. Bellwood (Ed.): Indo-Pacific Prehistory. Vol. 1, 1991, pp. 42-58.

- ↑ a b c Gudrun Corvinus: Homo erectus in East and Southeast Asia, and the questions of the age of the species and its association with stone artifacts, with special attention to handaxe-like tools. In: Quaternary International. Volume 117, Issue 1, 2004, pp. 141-151. doi: 10.1016 / S1040-6182 (03) 00124-1

- ↑ Sheela Athreya: What Homo heidelbergensis in South Asia? A test using the Narmada fossil from central India. In: Michael D. Petraglia, Bridget Allchin (Ed.): The Evolution and History of Human Populations in South Asia. Springer Verlag, Dordrecht 2007, pp. 137–170.

- ↑ KAR Kennedy, A. Sonakia, J. Chiment, KK Verma: Is the Narmada hominid an Indian Homo erectus? In: American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 86, 1991, pp. 475-496.

- ↑ Rothe Henke: Paleoanthropology. P. 461.

- ^ Gudrun Corvinus: A survey of the Pravara River system in western Maharashtra, India. Vol. 2: The Excavation of the Acheulian Site of Chirki-on-Pravara, India. (= Tübingen monographs on prehistory. Volume 2). Publishing house Archaeologica Venatoria, 1983.

- ↑ Rothe Henke: Paleoanthropology. Pp. 367 ff., 423

- ^ CC Swisher et al.: Latest Homo erectus of Java: Potential Contemporaneity with Homo sapiens in Southeast Asia. In: Science. Volume 274, 1996, pp. 1870-1874 ( abstract )

- ↑ Rothe Henke: Paleoanthropology. P. 422 ff.

- ^ Müller Karpe: Paleolithic. P. 96 f., 343 u. Plate 250

- ↑ Hoffmann: Lexicon of the Stone Age. P. 124.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica. 21, pp. 13-1b, 27, 1-b

- ↑ The abbreviation v. BC no longer makes sense with such periods, and they are only used in prehistoric research from the Neolithic. BP means: Before Present , the reference point is the year 1950.

- ↑ Hoffmann: Lexicon of the Stone Age. P. 124.

- ^ Müller-Karpe: Handbook of Prehistory: Paleolithic. P. 173 f.

- ↑ Kingdon: Human. P. 218.

- ↑ Kuckenburg: When man became the creator. P. 57 ff.

- ↑ Fagan: Departure from Paradise. Pp. 124 f., 132, 135, 240

- ^ Müller Karpe: Paleolithic. P. 98; Fiedler et al., P. 123.

- ^ Hahn: Artifacts. P. 188.

- ^ Lewin: Incarnation. P. 130.

- ^ Schäfer: manual. Pp. 237-247.

- ^ Schäfer: manual. Pp. 102 f., 113 f., 213, 278

- ↑ Kuckenburg: When man became the creator. Pp. 45-50.

literature

- Luigi L. and Francesco Cavalli-Sforza: Different and yet the same. A geneticist removes the basis of racism . Droemer Knaur, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-426-26804-3 .

- Encyclopedia Britannica . 32nd volumes. 15th edition. 1993, ISBN 0-85229-571-5 .

- Brian M. Fagan: Departure from Paradise. Origin and Early History of Humans . C. H. Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-35480-7 .

- Lutz Fiedler; Gaëlle and Wilfried Rosendahl: Old Stone Age A to Z . WBG, Darmstadt 2011, ISBN 978-3-534-23050-1 .

- Joachim Hahn: Recognition and determination of stone and bone artifacts. Introduction to artifact morphology . 2nd Edition. Publishing house "Archaeologica Venatoria" of the Institute for Pre- and Protohistory of the University of Tübingen, Tübingen 1993, ISBN 3-921618-31-2 .

- Winfried Henke; Hartmut Rothe: Paleoanthropology . Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York 1994, ISBN 3-540-57455-7 .

- Emil Hoffmann: Lexicon of the Stone Age . C. H. Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-42125-3 .

- St. Jones; R. Martin; D. Pilbeam: The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Evolution . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1995, ISBN 0-521-46786-1 .

- J. Kingdon: And man made himself. The risk of human evolution . Birkhäuser, Basel 1994, ISBN 3-7643-2982-3 .

- Martin Kuckenburg: When humans became creators. At the roots of culture . WBG; Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-608-94034-0 .

- Roger Lewin: Traces of the Incarnation. The evolution of Homo sapiens . Spektrum Akad. Verlag, Heidelberg 1992, ISBN 3-89330-691-9 .

- HL Movius: The Lower Palaeolithic Cultures of Southern and Eastern Asia . In: »Transact. American Philosophical Society NS «38, 1948, p. 329ff.

- Hermann Müller-Karpe: Handbook of Prehistory, Volume 1: Paleolithic. 2nd Edition. C. H. Beck, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-406-02008-9 .

- C. Scarre (Ed.): The Human Past . Thames and Hudson, London 2005, ISBN 0-500-28531-4 .

- Ernst L. Schäfer: The hand book. The left and the right. History and everyday life of our two sides . Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1988, ISBN 3-7700-0758-1 .

- Andrew Sheratt (Ed.): The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Archeology . Christian Verlag, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-88472-035-X .

- CC Swisher; WJ Rink; SC Antón; HP Schwarcz; GH Curtis; A. Suprijo Widiasmoro: Latest Homo erectus of Java: Potential Contemporaneity with Homo sapiens in Southeast Asia . In: " Science ". 274, 1996, pp. 1870-1874.