Nichiren Buddhism

Under Nichiren Buddhism ( Japanese 日 蓮 系 諸 宗派 , Nichiren-kei shoshūha ) one understands the different schools of Buddhism , which refer to the monk and scholar Nichiren (1222-1282), who lived in Japan in the 13th century. These schools form part of the so-called Hokke-shū (lotus school).

Core of Nichiren's teaching

For Nichiren, the Lotus Sutra , to which all Nichiren schools still refer to today, was the focus of Buddhist teaching and practice. According to Nichiren revealed Shakyamuni -Buddha the fact in this sutra that all people the Buddha nature inherent and enlightenment in the present existence is possible. This was in contrast to the widespread teaching of Amida Buddhism, which focused on rebirth in the “pure land” and was more oriented towards the hereafter. Nichiren set further priorities with the recitation of the mantra Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō (worship of the sutra of the lotus flower of the wonderful Dharma).

Gohonzon

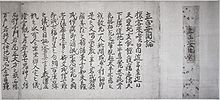

The Moji mandala Gohonzon or Mandala Gohonzon ( 曼荼羅 御 本尊 ) is a central object of worship in many schools of Nichiren Buddhism such as the Nichiren-shū . In the Nichiren Shoshu and Soka Gakkai , he is the only object of worship.

In Nichiren Buddhism, the Gohonzon as a mandala represents one of the three areas of worship (also known as "the three great secret dharmas ") of his teaching. The other two are the daimoku or Odaimoku " Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō " (a mantra) and the place (Kaidan), on which the Gohonzon is inscribed or where Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō is recited. Some Nichiren schools (e.g. the Nichiren Shōshū) see a central temple as a Kaidan, some also see the country of Japan as a whole.

The Nichiren Gohonzon is usually a calligraphic mandala, in the center of which Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō is written, surrounded by Buddhas, deities, demons and spirits, which represent their own life and thus represent Buddhahood as a whole. In addition, the arrangement of the individual elements on the Gohonzon symbolizes the so-called "ceremony in the air". The Gohonzon can, depending on the school, also be represented with the help of statues. In this metaphorical ceremony Shakaymuni Buddha proclaims the Lotus Sutra, the correctness of which is confirmed by the beings represented. The believer should therefore see himself as a participant in this ceremony. In the various Nichiren schools, however, there are different understandings of the role that the believer should be given as a participant in this metaphorical ceremony.

To this day there are still some Gohonzons made by Nichiren himself. Depending on the Nichiren School, copies of it are given to the believers, or master copies are made by priests on which copies are based for the believers. Thus, the Gohonzon represents the religious object or focus of worship for believers in Nichiren Buddhism. Most Nichiren schools, however, have in common that it is not the object itself, but what it is supposed to represent, that is worshiped.

Criticism of the state and established Buddhist schools

Nichiren, who was already a controversial figure during his lifetime and who criticized the relations between the then predominant Buddhist schools and the state, subsequently became the leading figure in a large number of Buddhist schools in Japan. His criticism was directed primarily against Zen Buddhism, Nembutsu and the schools of Shingon and Ritsu Buddhism, which enjoyed great popularity at court and among the people of 13th century Japan.

Nichiren, who himself was a priest of Tendai Buddhism, saw the reasons for Japan's predicament (wars with the Mongols , famines and natural disasters had weakened the country) in the fact that the government followed the Buddhist teachings mentioned above. In his opinion, these Buddhist schools deviated from the original teaching of Mahayana Buddhism. He also defended himself against the increasing influence of esoteric teachings in Tendai Buddhism. For this criticism, which he formulated in numerous writings such as the Risshō Ankoku Ron ( 立正 安 国 論 , translated: "About the pacification of the country through the establishment of the true (right) law"), he was sent into exile several times. According to legend, his execution was prevented by the appearance of a comet, which caused the executioner to drop his sword in shock and the soldiers present to flee.

Development of Nichiren Buddhism

Nichiren schools as such did not form until after Nichiren's death, because although there is evidence that he himself did not found his own school, he had entrusted six of his closest students and priests with passing on his teachings. These were: Nisshō , Nichirō , Nikkō , Nikō , Nichiji , and Nitchō . From these, after Nichiren's death, Nichiji set out to spread the Nichiren's teachings on the Asian mainland. However, he never returned from this undertaking.

In the following years the following schools were formed:

- the Minobu school of Nikō

- the Fuji school of Nikko

- the Hama school of Nisshō

- the Ikegami school of Nichirō

- the Nakayama school of Toki Jonin (stepfather of Nitchō).

Already in the 14th century there were first divisions within Nichiren Buddhism. A distinction is made between the Itchi line and Shoretsu line:

- The Itchi line unites the majority of the traditional Nichiren schools, including the later Nichiren-shū. Schools of this lineage revere the entire Lotus Sutra, both the so-called essential and theoretical part. Great importance, however, is given to the second, eleventh, and sixteenth chapters of the Lotus Sutra.

- The Shoretsu line, on the other hand, which includes a large part of the Nikkō temples, including the Nichiren shōshū and the Sōka Gakkai that emerged from it, underline the superiority of the essential part of the Lotus Sutra over the theoretical part. In the traditions of these schools, therefore, the second and sixteenth chapters are recited almost exclusively.

Although the various Nichiren temples were still loosely in contact with one another, the debate over the Itchi and Shoretsu questions forced the scholars of Nichiren Buddhism to take a stand.

During the 14th and 15th centuries, Nichiren Buddhist following grew steadily. In Japan entire localities converted to Nichiren Buddhism and in Kyōto only the temples of Zen outnumbered those of the Nichiren Buddhists. Even if the Nichiren temples were independent of each other, they met in a committee to solve common problems. Based on the teachings of Nichiren, the relationship between Nichiren followers and the state, as well as with other Buddhist schools that had the favor of the state on their side, remained problematic. It was above all the followers of the Fuju-Fuse who made this aspect of Nichiren's teachings an elementary part of their practice. Because of this, they mostly held their devotions in secret, and the persecution of Fuju-Fuse followers culminated in the execution and banishment of some of their members in 1668.

The majority of the "official" Nichiren temples were forced into a registration system during the Edo period , with the help of which the spread of Christianity should also be contained. In this Danka system , Buddhist temples were not only a place of learning and religious practice, but also closely integrated into an official administrative system. On the one hand, this system also narrowed down every missionary activity of the various Buddhist schools, on the other hand, however, the temples also received a steady income.

During the Meiji Restoration , some forces in the country, the Haibutsu kishaku movement, stepped up their efforts to completely ban Buddhism from Japan. Buddhist temples, like the temples of Nichiren Buddhism, were now forced to focus on funeral ceremonies and ceremonies in remembrance of the deceased. On the other hand, the state supported the development and promotion of the so-called State Shinto (see also Shinbutsu-Bunri and Shinbutsu-Shūgō ). This repressive policy was only relaxed towards the end of the Meiji period.

Although many traditional schools of Nichiren Buddhism refer to the founding date of their respective main temple as the founding year (Nichiren-shū the year 1281, Nichiren-Shōshū the year 1288 and Kempon Hokke-shū the year 1384), they were established as official Buddhist schools only from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, another wave of "mergers" followed in the 1950s.

What is interesting here is the split with regard to the Itchi and Shoretsu questions. This is one of the reasons for the clear separation in Nichiren-shū and Nichiren-Shōshū, another reason is the alleged succession disputes after Nichiren's death. In 1488, the Taiseki-ji priest Nikkyō discovered documents which were supposed to prove that Nichiren had designated his student Nikkō as his sole successor before his death or that he was granted a special position among the students of Nichichren. The discovered originals are believed to have been lost, but it is claimed that “real” copies are in the Taiseki-ji's possession. Other Nichiren schools consider these documents to be forgeries. Especially with regard to the Ikegami Honmon-ji , where Nikkō was also buried, the documents at the time of their "discovery" possibly served to underline the supposedly outstanding position of the Taiseki-ji temple within the Fuji lineage. In the further course of history, however, the later Nichiren-Shoshu mainly based its claim to orthodoxy on these documents, among other things. It is true that towards the end of the 19th century the Nikkō temples made efforts to unite into one school, the Kommon-ha . The Taiseki-ji temple, including the temples under it, eluded these attempts to unite the Nikkō temples around 1900 and officially called itself from 1913 Nichiren-Shōshū - in German the "True Nichiren School".

In some sources, even within Nichiren Buddhism, today's Nichiren Shōshū is also referred to as the Fuji school , which is historically only partially correct. At the time of its official founding, the Nichiren-shōshū comprised only the Taiseki-ji temple and a few smaller temples, which were formally subordinate to the Taiseki-ji.

Some Nikkō temples, which are thus ascribed to the historical Fuji school, such as the Ikegami Honmon-ji , Koizumi Kuon-ji and Izu Jitsujo-ji , joined the Nichiren-shū in the course of their history, which in turn was founded by Nichiren himself Kuon-ji as their main temple. The Hota Myohon-ji is now an independent temple. The Nishiyama Honmon-ji is the main temple of the Honmon Shoshū and the Kyoto Yobo-ji is now the main temple of the Nichiren Honshū . Today's Nichiren Shōshū is thus not identical to the historical Fuji lineage or Fuji school.

Nationalist expressions

Nichiren Buddhism has often been associated with Japanese nationalism ( Nichirenism ) and religious intolerance. On the one hand because Nichiren laid the foundation stone for a Buddhist school that apparently did not trace its roots back to a previous school on the Asian mainland, but this can be called into question by the connection to Tendai Buddhism. In addition, Nichiren Buddhism has always had a rather ambivalent relationship to the state in its history. Noteworthy are the events that became known as the incident on May 15 and at the center of which stood a priest, albeit a self-appointed priest of Nichiren Buddhism. An example of this is also the preacher and founder of the Kokuchūkai , Tanaka Chigaku . Also Tsunesaburō Makiguchi took before founding his own lay organization Soka Gakkai of, lectures Chigakus part. As a follower of Nichiren Buddhism, however, Chigaku also campaigned for support for the Kokutai idea.

On the other hand, these accusations also emerged against the more recent Nichiren movements of the 20th century. Especially in the Nichiren-shōshū, and the Sōka Gakkai that emerged from it, Nichiren is revered as Buddha. The idea of a Japanese Buddha could serve as an explanation for these allegations.

Main representative

Today there are around 40 different Buddhist schools, organizations and groups that refer to Nichiren. The most popular are listed in alphabetical order:

Schools of Nichiren Buddhism and their main temples

- Fuju-fuse Nichiren Kōmon-shū ( 不受 不 施 日 蓮 講 門 宗 本 山 本 覚 寺 )

- Hokke Nichiren-shū ( 法 華 日 蓮宗 総 本 山 宝龍 寺 )

- Hokkeshū, Honmon-ryū ( 法 華 宗 (本 門 流) 大本 山 光 長 寺 ・ 鷲 山寺 ・ 本 興 寺 ・ 本能 寺 )

- Hokkeshū, Jinmon-ryū ( 法 華 宗 (陣 門 流) 総 本 山 本 成 寺 )

- Hokkeshū, Shinmon-ryū ( 法 華 宗 (真 門 流) 総 本 山 本 隆 寺 )

- Hompa Nichiren-shū ( 本 派 日 蓮宗 総 本 山 宗祖 寺 )

- Honke Nichiren-shū (Hyōgo) ( 本 化 日 蓮宗 (兵 庫) 総 本 山 妙 見 寺 )

- Honke Nichiren-shū (Kyōto) ( 本 化 日 蓮宗 (京都) 本 山石 塔寺 )

- Honmon Butsuryū-shū , is sometimes also assigned to lay organizations ( 本 門 佛 立 宗 大本 山 宥 清 寺 )

- Honmon Hokke-shū : Daihonzan Myōren-ji ( 本 門 法 華 宗 大本 山 妙蓮 寺 )

- Honmon Kyōō-shū ( 本 門 経 王宗 本 山 日 宏 寺 )

- Kempon Hokke-shū : Sōhonzan Myōman-ji ( 総 本 山 妙 満 寺 )

- Nichiren Hokke-shū ( 日 蓮 法 華 宗 大本 山 正 福寺 )

- Nichiren Honshū: Honzan Yōbō-ji ( 日 蓮 本 宗 本 山 要 法 寺 )

- Nichiren Kōmon-shū ( 日 蓮 講 門 宗 )

- Nichiren-Shōshū : Sōhonzan Taiseki-ji ( 日 蓮 正宗 総 本 山 大石 寺 )

- Nichiren-shū Fuju-fuse -ha: Sozan Myōkaku-ji ( 日 蓮宗 不受 不 施 派 祖 山 妙 覚 寺 )

- Nichiren-shū : Sozan Minobuzan Kuon-ji ( 日 蓮宗 祖 山 身 延 山 久遠 寺 )

- Nichirenshū Fuju-fuse-ha ( 日 蓮宗 不受 不 施 派 )

- Shōbō Hokke-shū ( 正法 法 華 宗 本 山 大 教 寺 )

Organizations and movements based on Nichiren Buddhism

- Bussho Gonenkai Kyōdan , founded in 1950 by Kaichi Sekiguchi and Tomino Sekiguchi

- Fuji Taisekiji Kenshōkai (also just called Kenshōkai ; 富士 大石 寺 顕 正 会 ), founded in 1942, nationalistically oriented and excluded from the Nichiren Shōshū in 1978.

- Hokkekō Rengō Kai , lay group affiliated to the Nichiren Shōshū.

- Honmon Shōshū ( 本 門 正宗 )

- Kokuchūkai ( 国柱 会 , translated: Society for the Support of the Nation), an organization founded by Tanaka Chigaku in 1914 with a strong nationalistic character.

- Myōchikai Kyōdan , founded in 1950 by Miyamoto Mitsu.

- Myōdōkai Kyōdan , founded in 1951.

- Nichiren Buddhist Association of America, establishment dates unclear.

- Nipponzan-Myōhōji-Daisanga , founded in 1917 by Nichidatsu Fujii .

- Reiyūkai (translated: Society of Friends of Spirits), founded in 1925 by Kakutaro Kubo and Kimi Kotani.

- Risshō Kōsei Kai , a spin-off of the Reiyūkai founded in 1938 by Nikkyō Niwano and Myōkō Naganuma .

- Shōshinkai (translated: Society of Correct Belief), founded in 1980 and excluded from Nichiren Shōshū in 1981.

- Sōka Gakkai , founded in 1930 by Tsunesaburō Makiguchi . The Sōka Gakkai International was founded in 1975 by Daisaku Ikeda . Originally a lay organization within the Nichiren Shōshū, it was excluded from this in 1991 (or 1997).

Timetable

| year | Events |

|---|---|

| 1222 | Birth of Nichiren |

| 1251 | is seen in the Nichiren-shū as the year it was founded, see also 1876 |

| 1253 | Nichiren proclaims the mantra Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō |

| 1271 | Nichiren's banishment to the island of Sado |

| 1274 | Nichiren founds the Kuon-ji on Mount Minobu |

| 1276 | Foundation of the Tanjō-ji |

| 1281 | Establishment of Kyōnin-ji |

| 1282 | Nichiren's death, the Ikegami Honmon-ji is founded by Nichirō , |

| 1288 | Nikkō renounces the Kuon-ji |

| 1290 | Nikkō founds the Taiseki-ji , is regarded by the Nichiren-Shōshū as the year it was founded, see also 1922 |

| 1298 | Nichiji goes to China |

| 1307 | the Hōtō-ji is dedicated to a temple of the Nichiren-shū |

| 1358 | The Japanese imperial court awards Nichiren the title "Nichiren Daibosatsu" |

| 1384 | Nichiju founds the Kempon Hokke-shū |

| 1489 | Nichijin founds the Hokkeshū |

| 1580 | Establishment of the forerunner of Risshō University |

| 1595 | Foundation of the Fuju-Fuse , without official approval, recognition 1875/1878 |

| 1666 | Establishment of Nichiren Komonshū without official approval, recognition in 1875 |

| 1669 | Prohibition of Fuju-Fuse and execution of parts of the supporters |

| 1857 | Establishment of Honmon Butsuryū-shū , originally under the name "Honmon Butsuryū Ko", by Nagamatsu Nissen |

| 1884 | Founding of Kokuchūkai by Tanaka Chigaku still under the name "Risshō Ankokukai", since 1941 current name |

| 1876 | Formal establishment of the Nichiren-shū |

| 1917/1919 | Foundation of the Nipponzan-Myōhōji-Daisanga in Manchuria by Nichidatsu Fujii |

| 1922 | Formal establishment of the Nichiren Shōshū |

| 1925 | Founding of the Reiyūkai by Kakutaro Kubo and Kimi Kotani |

| 1931 | Mukden incident , Ishiwara Kanji is believed to be one of the main culprits. |

| 1932 | Incident on May 15 involving Inoue Nisshō |

| 1937 | Formal establishment of the Sōka Gakkai as a lay group within the Nichiren-Shōshū by Makiguchi Tsunesaburō still under the name Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai , which is why 1930 is sometimes given as the year of foundation. |

| 1938 | Foundation of the Risshō Kōseikai |

| 1942 | Foundation of the Kenshōkai as a lay group within the Nichiren Shōshū |

| 1949 | The Seichō-ji is dedicated to a temple of the Nichiren-shū |

| 1950 | Foundation of Myōchikai Kyōdan |

| 1951 | Foundation of Myōdōkai Kyōdan |

| 1956 | Ishibashi Tanzan , originally a Nichiren-shu monk, becomes the 36th Prime Minister of Japan |

| 1964 | Foundation of the Kōmeitō |

| 1973 | Exclusion of the Kenshōkai from the Nichiren Shōshū |

| 1975 | Sōka Gakkai International, as an international branch of Sōka Gakkai, is founded |

| 1980 | Foundation of the Shōshinkai |

| 1992 | Exclusion of Daisaku Ikeda and other leaders of the Sōka Gakkai from the Nichiren-Shōshū |

| 1997 | Exclusion of all followers who remained with the Sōka Gakkai from the Nichiren-Shōshū |

| 1998 | Dissolution of Kōmeitō, establishment of the "New Kōmeitō", later renamed again to Kōmeitō |

| 2005 | Foundation of the Renkoji in Italy |

Individual evidence

- ^ The Nichiren Mandala Study Workshop: The Mandala in Nichiren Buddhism . In: Mandalas of the Koan period . tape 2 . Library of Congress, USA 2014, ISBN 978-1-312-17462-7 , pp. 218 ff .

- ^ Stone, Jacqueline, I. "Chanting the August Title of the Lotus Sutra: Daimoku Practices in Classical and Medieval Japan". In: Payne, Richard, K. (ed.); Re-Visioning Kamakura Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1998, p. 117. ISBN 0-8248-2078-9

- ^ The Nichiren Mandala Study Workshop: Mandalas of the Koan period . In: The mandala in Nichiren Buddhism . tape 2 , catalog no. 81 . Library of Congress, USA 2014, ISBN 978-1-312-17462-7 , pp. 150 ff .

- ↑ Shutei Mandala ( Memento of the original from July 9, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Nichikan Gohonzon Declaration (English)

- ↑ Rissho Ankoku Ron: Annotated version of a priest of the Nichiren-shū, English ( Memento from July 1, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Ryuei Michael McCormick: History of Nichiren Buddhism, The Kyoto Lineages. ( Memento from March 24, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ A response to questions from Soka Gakkai practitioners regarding the similarities and differences among Nichiren Shu, Nichiren Shoshu and the Soka Gakkai. ( Memento of the original from June 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 293 kB) on: nichiren-shu.org

- ^ Daniel B. Montgomery: Fire in the Lotos. Pp. 175-176.

- ^ Daniel B. Montgomery: Fire in the Lotos. P. 160.

- ↑ Nichiren Buddhism. on: philtar.ac.uk

- ↑ Tamamuro Fumio, "Local Society and the Temple-Parishioner Relationship within the Bakufu's Governance Structure", Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 28 / 3-4 (2001), p. 261. Digitized version ( Memento of October 29, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 219 kB)

- ^ Daniel B. Montgomery: Fire in the Lotos. P. 169.

- ^ Daniel B. Montgomery: Fire in The Lotus. Mandala 1991, p. 150.

- ↑ Honmon Shoshu

- ↑ William H. Swatos: Encyclopedia of religion and society. Alta Mira Press, 1998, p. 489.

- ^ Levi McLaughlin in: Inken Prohl, John Nelson (Ed.): Handbook of Contemporary Japanese Religions. (Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion, Volume 6). Brill, Leiden et al. 2012, ISBN 978-90-04-23435-2 , p. 281.

- ↑ Jacqueline I. Stone: By Imperial Edict and Shogunal Decree. In: Steven Heine, Charles S. Prebish (Eds.): Buddhism in the Modern World. Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-19-514698-0 , p. 198. (online at: princeton.edu )

- ↑ James Wilson White: The Sōkagakkai and mass society. Stanford University Press, 1970.

- ^ Daniel B. Montgomery: Fire in The Lotus. Mandala 1991, pp. 280-282

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Daniel B. Montgomery: Fire in The Lotus : Mandala 1991, p. 280.

literature

- Margareta von Borsig (ex.): Lotos Sutra - The great book of enlightenment in Buddhism. Herder Verlag, new edition 2009. ISBN 978-3-451-30156-8 .

- Richard Causton: The Everyday Buddha: Introduction to Nichiren Daishonin's Buddhism ; Moerfelden-Walldorf: SGI-D 1998; ISBN 3-937615-02-4 .

- A Dictionary of Buddhist Terms and Concepts. Nichiren Shoshu International Center, ISBN 4-88872-014-2 .

- Katō Bunno, Tamura Yoshirō, Miyasaka Kōjirō (tr.), The Threefold Lotus Sutra: The Sutra of Innumerable Meanings; The Sutra of the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Law; The Sutra of Meditation on the Bodhisattva Universal Virtue , Weatherhill & Kōsei Publishing, New York & Tōkyō 1975 PDF (1.4 MB)

- Matsunaga, Daigan, Matsunaga, Alicia (1996), Foundation of Japanese Buddhism, Vol. 2: The Mass Movement (Kamakura and Muromachi Periods), Los Angeles; Tokyo: Buddhist Books International, 1996. ISBN 0-914910-28-0 .

- Murano, Senchu (tr.). Manual of Nichiren Buddhism, Tokyo, Nichiren Shu Headquarters, 1995

- Lotus Seeds, The Essence Of Nichiren Shu Buddhism. Nichiren Buddhist Temple of San Jose, 2000. ISBN 0-9705920-0-0 .

- Yoshiro Tamura: Japanese Buddhism, A Cultural History. Kosei Publishing, Tokyo 2005, ISBN 4-333-01684-3 .

- Yukio Matsudo: Nichiren, the practitioner of the Lotus Sutra. Books on Demand, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8370-9193-9 .

- Helen Hardacre (1984). Lay Buddhism in Contemporary Japan: Reiyukai Kyodan, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-07284-5 .

- The Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism, Soka Gakkai, 2002. ISBN 4-412-01205-0 online

- Stone, Jacqueline (2003). Nichiren's activist heirs: Sõka Gakkai, Risshõ Kõseikai, Nipponzan Myõhõji. In Action Dharma: New Studies in Engaged Buddhism, ed. Queen, Christopher, Charles Prebish, and Damien Keown, London, Routledge Curzon, pp. 63–94.

Translations of Nichiren's writings

- The Gosho Nichiren Daishonins, Volumes I to IV, published by Soka Gakkai Germany, Mörfelden-Walldorf 1986–1997

- The Gosho Translation Committee (transl.): The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, Volume I , Soka Gakkai, 2006. ISBN 4-412-01024-4 .

- The Gosho Translation Committee (transl.): The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, Volume II , Soka Gakkai, 2006. ISBN 4-412-01350-2 .

- Kyotsu Hori (transl.); Sakashita, Jay (Ed.): Writings of Nichiren Shonin , Doctrine 1, University of Hawai'i Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8248-2733-3 .

- Tanabe Jr., George (ed.), Hori, Kyotsu: Writings of Nichiren Shonin , Doctrine 2, University of Hawai'i Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8248-2551-9 .

- Kyotsu Hori (transl.), Sakashita, Jay (Eds.): Writings of Nichiren Shonin , Doctrine 3, University of Hawai'i Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8248-2931-X .

- Kyotsu Hori (transl.), Jay Sakashita (ed.): Writings of Nichiren Shonin , Doctrine 4, University of Hawai'i Press, 2007, ISBN 0-8248-3180-2 .

- Kyotsu Hori (transl.), Sakashita, Jay (Eds.): Writings of Nichiren Shonin , Doctrine 5, University of Hawai'i Press, 2008, ISBN 0-8248-3301-5 .

- Kyotsu Hori (transl.), Sakashita, Jay (Eds.): Writings of Nichiren Shonin , Doctrine 6, University of Hawai'i Press, 2010, ISBN 0-8248-3455-0 .