Pandeism

Pandeism (from ancient Greek πᾶν pān “everything” and Latin deus , “God”) describes a conception of God that combines metaphysically shaped pantheism (God is the universe) and deism (God created the universe) .

It is the belief “that God created the universe, is now one with it, and therefore not a separate conscious being.” Therefore it does not have to be worshiped, because God is nature incarnate.

Concept and delimitation

The term was probably coined in 1859 by Moritz Lazarus and Heymann Steinthal . The first comprehensive presentation of pandeism comes from Max Bernhard Weinstein in world and life views, which emerged from religion, philosophy and knowledge of nature (Leipzig 1910). For Weinstein, the distinction between pantheism and pandeism is of fundamental importance.

The main features of pandeism:

- There is a God as Creator who does not need to be worshiped.

- Because God became the universe with creation.

- Everything that is exists not only through God but also in God.

- God is not a separate being - he is immanent and not transcendent.

While deism postulates a complete separation of God and the world, pandeism assumes that God and the world form a unit after creation, and in contrast to pantheism, pandeism postulates an act of creation. The panentheism other hand represents the idea that the world is a part of an evolving deity - so immanent and transcendent - and would also depend on God during pandeism only accepts immanence and transcendence and thus no independence from God.

Pandemic ways of thinking

Max Bernhard Weinstein saw the earliest evidence of pandeism in the ancient Egyptians , namely in the belief that primordial matter emerged from the primordial spirit. There were similar ideas among the Sumerians . Weinstein also sees numerous pandeistic ways of thinking in Asian philosophy. In China, for example, with Laotse or Taoism . In India in the idea of Brahma and in the Bhagavad Gita .

“In the Bhagavad-Gītā, Krishna-Vishnu says of himself to the Arjuna: he is the origin and fall of all things, the power in all things and the appearances, fragrance in wine, shine in the sun, moon and stars, sound in the word, even everyone Letter, every song, Himalayan mountains, fig tree, horse, human being, snake (every animal in general), every season. As he shows himself to Arjuna afterwards as a deity, he sees, besides infinite radiance, the universe united in him:

"All beings, all gods, see I hang on your body,

Brahma on the lotus position, including the seers and the snakes,

Many faces, arms, bodies, many eyes, you mighty one;

But I see neither goal nor beginning in you, multi-faceted ... «"

Wen Chi described in a lecture at Peking University in 2002 pandeism ( Chinese :泛自然神论) as an essential feature of philosophical thought in China.

For Weinstein, some well-known representatives of Western philosophy are pandeists, such as Scotus Eriugena , Giordano Bruno , Anselm von Canterbury , Nikolaus von Kues , Lessing and Moses Mendelsohn .

The American philosopher William C. Lane described pandeism as a logical derivation of the postulate " The best of all possible worlds " (including from Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz ' theodicy ). Lane did not accept the theodicy problem (why there is suffering in the world) "not as an argument against pandeism, because in pandeism God is not a heavenly supervisor who would be able to intervene hourly in earthly affairs."

According to American Philosophy: An Encyclopedia, “later Unitarian Christians (such as William Ellery Channing ), transcendentalists (such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau ), writers (such as Walt Whitman ), and some pragmatists (such as William James ) persecuted a more pantheistic or pandemic Approach by rejecting the view of God as separate from the world. "

Pandeists in literature include Alfred Tennyson , Fernando Pessoa , Carlos Nejar , and Robert A. Heinlein , who wrote, “God split into myriads of parts to make friends. That may not be true, but it sounds good - and is no more simple-minded than any other theology. "

Criticism of pandeism

Political scientist Jürgen Hartmann claims that the contrast between Hindu pandeism and monotheistic Islam divides Indian society.

The American philosopher Charles Hartshorne sees panentheism as the integration of deism , pandeism and pantheism without their arbitrary negations.

Pandeism in the present

The literary scholar and literary critic Martin Lüdke wrote in 2004 about the work of Alberto Caeiro by Fernando Pessoa : “Caeiro undermines the distinction between appearances and what, for example, 'thinkers' thoughts' want to distinguish behind him. Things as he sees them are what they seem. His pan-deism is based on a metaphysics of things that should still set a school in modern poetry of the twentieth century. "

In 2001, the Dilbert creator Scott Adams propagated a form of pandeism in the non-humorous parable God's Debris: A Thought Experiment (in German, for example: "God's Trümmer: Ein Denkexperiment ").

The social scientist Charles Brough counts pandeism as one of the few beliefs that are compatible with modern science. Raphael Lataster, religious philosopher and researcher at the University of Sydney (Religious Studies), believes that pandeism could be the most likely of all ideas about God.

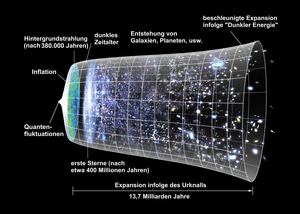

In a broadcast on SWR in 2010, astrophysicist Harald Lesch quoted Nobel Prize winner Hannes Alfvén : “Let us assume that we would find the all-encompassing law of nature that we are looking for, so that we can finally proudly assure that it is so and no different the world built - immediately a new question would arise: What is behind this law, why is the world built in this way? This why leads us beyond the limits of natural science into the realm of religion. As a professional, a physicist should answer: We don't know, we will never know. Others would say that God made this law, that is, created the universe. A pandeist might say that the all-embracing law is God. "

In a 2011 report on the religions in Hesse, Michael N. Ebertz and Meinhard Schmidt-Degenhard wrote : “Six types of religious orientation can be distinguished: 'Christians', 'Non-Christian theists', 'cosmotheists', 'Deists, pandeists and polytheists'. , 'Atheists' and 'Others'. "

See also

literature

- Max Bernhard Weinstein : World and life views, emerged from religion, philosophy and knowledge of nature. Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig 1910, archive.org

- Ph. Clayton, A. Peacocke (Eds.): In Whom We Live and Move and Have Our Being. Panentheistic Reflections on God's Presence in a Scientific World . Eerdman Publishing, Cambridge 2004, ISBN 978-0-8028-0978-0 .

- Christoph Wand: Time and solitude. A speculative draft for teaching theology and physics following the analysis of time by Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker . LIT-Verlag, Münster 2007, ISBN 978-3-8258-0899-0 .

- Alan H. Dawe: The God Franchise: A Theory of Everything. 2011, ISBN 0473201143 .

- Raphael Lataster: There was no Jesus, there is no God: A Scholarly Examination of the Scientific, Historical, and Philosophical Evidence & Arguments for Monotheism. 2013, ISBN 978-1492234418 .

Web links

- The Parallels of Pandeism by Bernardo Kastrup

- Discussion of Creative Evolution (from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy ).

- Koilas - A Pandeistic Religion

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Raphael Lataster: There was no Jesus, there is no God: A Scholarly Examination of the Scientific, Historical, and Philosophical Evidence & argument for monotheism. 2013, ISBN 1492234419 , p. 165: “This one god could be of the deistic or pantheistic sort. Deism might be superior in explaining why God has seemingly left us to our own devices and pantheism could be the more logical option as it fits well with the ontological argument's 'maximally-great entity' and doesn't rely on unproven concepts about 'nothing' (as in 'creation out of nothing'). A mixture of the two, pandeism, could be the most likely God-concept of all. "

- ^ Alan H. Dawe: The God Franchise: A Theory of Everything. 2011, ISBN 0473201143 , p. 48.

- ^ Moritz Lazarus , Heymann Steinthal : Journal for Völkerpsychologie und Sprachwissenschaft. 1859, p. 262: "So it is up to the thinkers whether they are theists, pantheists, atheists, deists (and why not pandeists too?) ..."

- ^ Max Bernhard Weinstein: Welt- und Lebenanschauungen, emerged from religion, philosophy and knowledge of nature. Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig 1910, ( Online ), p. 227: "Even if only by a letter ( d instead of th ), we fundamentally differentiate pandeism from pantheism."

- ↑ Rudolf Eisler, Karl Roretz: Dictionary of philosophical terms . Historically and source-wise edited by Rudolf Eisler. Continued and completed by Karl Roretz. 4., completely reworked. Aufl. Mittler, Berlin 1929, p. 370.

- ↑ LB Puntel: His and God. A systematic approach in dealing with M. Heidegger, E. Levinas and J.-L. Marion (Philosophical Investigations, 26). Tübingen 2010.

- ^ Max Bernhard Weinstein: Welt- und Lebenanschauungen, emerged from religion, philosophy and knowledge of nature. Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig 1910 ( Online ), p. 155: "So it will probably be a matter of a primordial matter in connection with a primordial spirit, which corresponds to the pandemic direction of the Egyptian views"; P. 228: "But with the Egyptians, pandeism is said to be expressed more fully."

- ^ Max Bernhard Weinstein: Welt- und Lebenanschauungen, emerged from religion, philosophy and knowledge of nature. Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig 1910 ( Online ), p. 121: "So it is not correct if the views of the Chinese are equated with those of indigenous peoples, rather they actually belong to pandeism instead of pananimism, namely a dualistic one."

- ^ Max Bernhard Weinstein: Welt- und Lebenanschauungen, emerged from religion, philosophy and knowledge of nature . Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig 1910 ( online ), p. 229.

- ↑ Definition of 泛 自然神論 (泛 自然神论, fànzìránshénlùn ) from CEDICT, 1998: “pandeism, theological theory that God created the Universe and became one with it.”

- ↑ 文 池 (Wen Chi): 在 北大 听讲座: 思想 的 灵光(Lectures at Peking University: Thinking of Aura). 2002, ISBN 7800056503 , p. 121: 在 这里, 人 与 天 是 平等 和谐 的, 这 就是说, 它 是 泛 自然神论 或是 无神论 的, 这 是 中国 人文 思想 的 一 大 特色。Translation: “Here, there is a harmony between man and the divine, and they are equal, that is to say, it is either Pandeism or atheism, which is a major feature of Chinese philosophical thought. "

- ↑ Otto Kirn: Welt- und Lebensanschauungen, emerged from religion, philosophy and knowledge of nature. In: Emil Schürer, Adolf von Harnack (ed.): Theologische Literaturzeitung , Vol. 35, 1910, column 827.

- ^ A b William C. Lane: Leibniz's Best World Claim Restructured. (Retrieved March 9, 2014) In: American Philosophical Journal. 47, No. 1, January 2010, pp. 57–84: “If divine becoming were complete, God's kenosis - God's self-emptying for the sake of love - would be total. In this pandeistic view, nothing of God would remain separate and apart from what God would become. Any separate divine existence would be inconsistent with God's unreserved participation in the lives and fortunes of the actualized phenomena. ... However, it does not count against pandeism. In pandeism, God is no superintending, heavenly power, capable of hourly intervention into earthly affairs. No longer existing 'above,' God cannot intervene from above and cannot be blamed for failing to do so. Instead God bears all suffering, whether the fawn's or anyone else's. Even so, a skeptic might ask, 'Why must there be so much suffering? Why could not the world's design omit or modify the events that cause it? ' In pandeism, the reason is clear: to remain unified, a world must convey information through transactions. Reliable conveyance requires relatively simple, uniform laws. Laws designed to skip around suffering-causing events or to alter their natural consequences (i.e., Their consequences under simple laws) would need to be vastly complicated or (equivalently) to contain numerous exceptions. "

- ↑ John Salmon: Robert Talisse: American Philosophy: An Encyclopedia. 2007, ISBN 0415939267 , p. 310: “Later Unitarian Christians (such as William Ellery Channing ), transcendentalists (such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau ), writers (such as Walt Whitman ) and some pragmatists (such as William James ) took a more pantheist or pandeist approach by rejecting views of God as separate from the world. "

- ^ Gene Edward Veith, Douglas Wilson, G. Tyler Fischer: Omnibus IV: The Ancient World. 2009, ISBN 1932168869 , p. 49: “Alfred Tennyson left the faith in which he was raised and near the end of his life said that his 'religious beliefs also defied convention,' leaning towards agnosticism and pandeism.”

- ↑ Giovanni Pontiero: carlos nejar, poeta e pensador. 1983, p. 349: «Otávio de Faria póde falar, com razão, de um pandeísmo de Carlos Nejar . Não uma poesia panteísta, mas pandeísta. Quero dizer, uma cosmogonia, um canto geral, um cancioneiro do humano e do divino. Mas o divino no humano. " Translation: “Otávio de Faria spoke of the pandeism of Carlos Nejar . Not a pantheist poetry, but pandeist. I want to say, a cosmogony, one I sing generally, a chansonnier of the human being and the holy ghost. But the holy ghost in the human being. "

- ↑ Otávio de Faria: Pandeísmo em carlos nejar. In: Última Hora. Rio de Janeiro, May 17, 1978: “Se Deus é tudo isso, envolve tudo, a palavra andorinha, a palavra poço oa palavra amor, é que Deus é muito grande, enormous, infinito; é Deus realmente eo pandeismo de Nejar é uma das mais fortes ideias poéticas que nos têm chegado do mundo da Poesia. E o que nicht pode esperar desse poeta, desse criador poético, que em pouco menos de vinte anos, já chegou a essa grande iluminação poética? » Translation: “If God is all, involves everything, swallows every word, the deep word, the word love, then God is very big, huge, infinite; and for a God really like this, the pandeism of Nejar is one of the strongest poetic ideas that we have reached in the world of poetry. And could you expect of this poet, this poetic creator, that in a little less than twenty years, he has arrived at this great poetic illumination? "

- ^ Dan Schneider: Review of Stranger In A Strange Land (The Uncut Version), by Robert A. Heinlein. (7/29/05).

- ^ Time Enough For Love, 1973 ; Original wording : “God split himself into a myriad parts that he might have friends. This may not be true, but it sounds good - and is no sillier than any other theology. "

- ↑ Jürgen Hartmann : Religion in Politics: Judaism, Christianity, Islam. Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-658-04731-3 , p. 237: “Even if the Muslims in the big city wanted to build their closed little worlds, there was always friction with the Hindu majority society: caste system vs. . Equality of the Muslims, meat consumption of the Muslims vs. Hindu vegetarianism, Muslim monotheism vs. Pandeism and veneration of saints among the Hindus. "

- ^ Charles Hartshorne : Man's Vision of God and the Logic of Theism. 1941, ISBN 0-208-00498-X : “Panentheistic doctrine contains all of deism and pandeism except their arbitrary negations.”

- ↑ Martin Lüdke : A modern guardian of things; The discovery of the great Portuguese continues: Fernando Pessoa saw Alberto Caeiro's poetry as his master. In: Frankfurter Rundschau , August 18, 2004.

- ↑ Scott Adams: God's Debris. 2001, ISBN 0-7407-2190-9 , p. 43.

- ^ Charles Brough: Destiny and Civilization - The Evolutionary Explanation of Religion and History. 2008, ISBN 1438913605 , p. 295.

- ↑ to: Südwestrundfunk SWR2 auditorium - manuscript service (transcript of a conversation): "God plus Big Bang = X - Astrophysics and Faith (2)." Discuss: Professor Hans Küng and Professor Harald Lesch , editors: Ralf Caspary, broadcast: Sonntag , May 16, 2010, 8:30 a.m., SWR2 (quote from 1970 Nobel Prize winner Hannes Alfvén by astrophysicist Harald Lesch).

- ↑ Quotation in the program Gott plus Big Bang (2) (SWR2 Aula from May 16, 2010), 1:32 seconds.

- ↑ Michael N. Ebertz, Meinhard Schmidt-Degenhard: What do the Hessians believe? Horizons of religious life. 2014, p. 82.