Puinave

Coordinates: 4 ° 0 ′ 23 " N , 67 ° 41 ′ 56" W.

The Puinave are located southwest of San Fernando de Atabapo , mainly along the Río Inírida

|

The Puinave are a small indigenous ethnic group in the Colombian border area with Venezuela.

language

Their language is the Puinave ( ISO 639 : PUI), which is related to the Makú. The Makú languages should not be confused with the practically extinct Máku in northern Brazil. The Puinave in the area of the Río Mirinda have mostly given up their ancestral language in favor of the Kurripako .

| Maku |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Demographics

It is believed that the Puinave people max. Includes 3200 tribal members.

Settlement area

geography

The Puinave live in the Colombian border area with Venezuela, at the confluence of the Río Guaviare , Río Inírida and the Orinoco , south of San Fernando de Atabapo , adjacent in the north to the De'áruwa and Maku and in the south to the Wakuénai .

Their settlement area is at the transition from the forest (Selva amazónica) to the savannah (Llanos de la Orinoquia).

climate

The climate is hot and humid, with an average annual temperature of 27 ° C. From May to October the rainy season prevails with approx. 15 rainy days per month, from January to March dry season with max. 7 rainy days per month.

Political Affiliation

Politically, their settlement area is in the Colombian states of Guainía and Vichada and in the Venezuelan state of Amazonas .

history

The Puinave are originally from Colombia. However, when they came to the Inírida region remains largely in the dark.

In the 16th century, they moved to the Rio Macuco because Jesuit missionaries tried to settle them in mission stations.

A map from 1741 shows that at that time they settled at the confluence of the Río Inírida, Río Nooquéne and Orinoco, in the vicinity of the Caberre tribe .

Since the early 19th century, their lives have been influenced by rubber collectors, settlers, cattle farmers and evangelical missionaries, primarily through deadly introduced diseases.

Since around 1960, the Puinave have increasingly mixed with their neighboring peoples, especially with the Wakuénai .

In the past they only settled in the same place for a short time, living in villages for a short time. This nomadic way of life was given up with the contact with the criollos , the introduction of wage labor and the resulting dependence, they settled down and now live in houses.

Most of them now live in settlements around Guasuripana and San Fernando de Atabapo. Many in Colombia also live in Indian reservations, such as: Remanzo-Chorro Bocón (490 Ew.), Coayare-El Choco (184 Ew.), Caranacoa-Yuri-Laguna Morocoto (326 Ew.), Almikdon-La Gelba (138 Ew. ), Bachaco Buena Vista (186 Ew.), Guaco Bajo y Guaco Alto (265 Ew.) And Cano Bocón Brazo Amanaven (103 Ew.).

Each village and its surrounding territory are the collective property of all residents.

Nowadays the Puinave hardly differ from the local mixed population. The men wear shirts and trousers and the women brightly colored cotton dresses. You speak Spanish well and mostly use industrially manufactured household products.

The Puinave population has been decimated by introduced diseases and they currently have high tuberculosis rates .

In Venezuela, the indigenous people make up only 2% of the population, next to 60% criollos, 20% Europeans and 8% Africans.

economy

Division of labor

Women collect, cultivate the fields, manufacture textiles. Men fish, hunt and rule the social system.

Food production

Agriculture and fishing take precedence over gathering and hunting .

They use a star calendar that determines the seasons, thus the time for sowing and harvesting and the reproductive cycles of the animals.

Collect

Fruits , nuts , seeds , wild vegetables , herbs , roots , mushrooms , eggs and honey are collected .

Agriculture

The Puinave differentiate between different soils and use them according to their suitability. Staple food and thus the main crop is cassava , which to Casabe and Manoco is processed.

Their agriculture is based on a kind of three-field economy :

- The first field is planted with cassava after a forest area was cleared in late March before the start of the rainy season .

- The cassava grows in the second field.

- The third field is harvested, then either left or z. B. planted with fruit trees.

Fishing

Fishing is economically relevant for the Puinave and is fished all year round in this river-rich, fish-rich landscape with different techniques.

In the dry season, fishhooks, harpoons and bows and arrows are used, in the rainy season fish pots (nasas) and nets (cacures) are used. Fishing with Barbasco extract and other plant poisons is a festive event in which women and children also take part.

hunt

The weapons traditionally used for hunting are made of hardwood, if made of stone, the blades are more likely to be found objects. The most common hunting weapon is the blowgun , the arrows of which are poisoned with curare . Mainly small game such as birds, monkeys and armadillos are hunted . Large game such as pecaris (banquiro) and tapirs are also shot, albeit rarely. Pakas and Agutís (Picure) are also captured using pitfalls , snare, box or snap traps . Predator trophies such as caiman and jaguar teeth are used to make ritual objects and jewelry.

Nowadays, however, only firearms are used to generate hunting proceeds in the form of skins and leather for trade, which is now leading to a serious decimation of the once rich game population.

Pet ownership

Domestic animals are neglected, agoutis or pecaris caught alive are fed until slaughter.

Crafts and handicrafts

Traditional tools, weapons, cult objects and other consumer goods were made exclusively from vegetable and animal raw materials.

- Metalworking was never in use, although there are iron ore and gold veins in the Parima. Even the processing of stone tools was hardly available among the Puinave.

- Textile production : Hammocks made from fibers of the Moriche palm and Cumare palm (Astrocaryum aculeatum), using simple looms, are the most famous products of the region.

- Ceramic production : Old ceramic plates and their modern, commercial replicas , painted with anthropomorphic images, are offered at the Indian market in San Fernando de Atabapo.

- Wood processing : Carved animal-shaped stools, which were previously ritual objects of their holy people, are also sold there.

Nowadays, the Puinave no longer produce textiles, wickerwork and ceramics for their own use , but instead buy cotton clothing and aluminum or plastic tableware from the Criollos.

trade

Traditionally, income is initially intended for personal use and surpluses from hunting and fishing are distributed within the group.

However, the advance of civilization has also led to a change of attitude among the Puinave, and Western economic thinking undermines solidarity within the tribal groups.

The cassava products Casabe and Mañoco, which hold up particularly well in the hot and humid climate, are traded locally.

Deliveries of goods by the Puinave include fish, hides and hides, wood, rubber and other marketable treasures of the forest. In return, they get soap, salt, canned food, textiles, radios, outboard motors and gasoline, firearms and ammunition from local traders.

Wage labor

The traders' credit system (“first payment, then delivery”) binds the indigenous people and repeatedly leads them to exploit their resources.

This dependency system has brought the traditional trade with the other tribes to a collapse and negatively influenced the life of the indigenous people.

traffic

Freight and passenger traffic takes place almost exclusively on the extensive river system of the Orinoco, by means of dugout canoes (bongos), freighters and push convoys.

Social structures

Real estate, property and housing

A tribal territory was once owned by small patrilateral groups of five or six families.

Today's villages and the surrounding territory are still collective property and the families have individual rights to agricultural land, to collecting areas and to fishing rights, but the population of the villages is heterogeneous and the tribal chief is often a Protestant pastor of Indian origin.

Family education

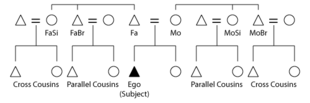

Puinave differentiates between cross-cousin and parallel- cousin marriage in their marriage rules : marriages with cross-cousins are desirable (daughter of father sister or mother brother), but prohibited with parallel cousins (daughter of father brother or mother sister).

Newlyweds live with the wife's family during the period of the bridal service . Then both move to the husband's village (see Viri locality ).

The Puinave increasingly mix with groups who speak other languages, mainly with the Curripaco ( Baniwa ) and Wakuénai , but also with the Vaupé .

Beliefs, religion and worldview

Their traditional social structures and ethnic belief systems were largely intact until 1943. Despite the strong influence of western civilization, the memory of the ancestral dynamic world concept is still alive.

Pantheon of gods

- Qátari (A'íopo)

- Túpana (Dukjin, Tudon)

- Maunduddua

- Amarrundua

- Yopinai (Maunduddua)

- The monkey

Creation myth

For the Puinave, their settlement area is the center of the world and the continuity of “becoming and passing” is divided into several ages.

In the beginning, a human race existed above the clouds that now cover the earth. They were well formed, of good disposition, and lived in peace with one another.

However, one monkey began to cause strife and its intrigues resulted in a terrible war that wiped out all but one woman. This woman collected the bones of the fallen and dried them. From these bones four siblings emerged, the brothers Qátari (A'íopo) and Túpana (Tudon) and the sisters Maunduddua and Amarrundua. Túpana was small and ailing. The woman strengthened him with the help of the sun's rays.

Qátari, the eldest of the brothers, meanwhile created the universe with the sun, moon and stars, but he did not complete the earth.

One of the siblings was murdered and his bones became the cultural hero Dukjin (Túpana), who created mountains and rivers, animals, birds, fish and fruits of the forest. When Túpana was a man, he killed the woman and created from her flesh the dwarfs who lived underground. And when it was night in the underworld, the sun shone in the upper world. The dwarves ate casabe and mañoca because there were no fish in the rivers, and the animals of the underworld were too big to kill.

Túpana completed the creation of the world, descended from the heavenly world, got into the hole in the center of the earth and called the dwarfs together by blowing his trumpet, which he had rolled out of a platanillo leaf . That was near the rapids of Cupipan , the center of the world. When Túpana saw that they were dwarfs, he blew them through a tobacco leaf and made them bigger. He built them houses. He taught the men the use of bows and arrows and the manufacture of dugouts and oars, cassava grinders and cassava sieves, and the art of weaving. He showed the women how things like textiles and hammocks are made from plant fibers. He showed everyone how to make a fire, how to prepare food, how to plant and process cassava and how to make ceramics out of clay. Dukjin (Túpana) taught the men to hunt and fish, as well as the formation of tribal communities, rituals and laws, such as the rules of marriage.

The men did not appreciate the efforts of Túpana and came up with a plan to kill Túpana. Thereupon Túpana called the water from the hole inside the earth and a great flood destroyed almost all of the first humans.

Furthermore, Túpana created the demon goddess Yopinai, who gave women the power to enslave men. Under the rule of Yopinai women were the masters of rituals (→ shamans ) ; they danced, sang, and made human sacrifices. Men were excluded from these rituals.

When Yopinai ordered all the boys to be killed, the women also revolted against the demoness. Yopinai then ordered the women to eat only coal and earth in order to become sterile. When the men returned from the forest after the exile at the time of the rituals of women and found their wives thin and sick, they killed Yopinai and burned them. Seje palms , manaca palms and other fruit-bearing trees grew out of the ashes of the demoness . And the men took over the rule of the tribes again.

When Túpana saw all of this, he realized that Yopinai was evil and that the people rightly killed her and condemned her to the underworld. He wanted to bring stability to the world and therefore let fruit grow, created the rainy season, lightning, thunder and wind.

The spirit of Yopinai returned to the underworld, and from their bones, which had remained in the ashes, the people created the sacred wind instruments, over whose possession disputes broke out as a result. Túpana then took the sacred wind instruments and sank them in the hole in the center of the world.

He ordered the people to make wooden wind instruments, like those made from the bones of the Yopinai, to pay homage to him and to keep Yopinai in check. These wooden wind instruments are still played today at the Yurupari Festival, where the Puinave express their bond with their ancestors from mythical times.

And as long as they play the flutes (majuari), Yopinai can no longer gain power over the Puinave.

animism

The ethnic religion of the Indigenas des Parimas is animistic , which means that even the smallest part has a cosmos that is comparable to the human soul. For them, the spiritual world is the real reality.

Transformation and Metamorphosis

The awe-inspiring knowledge of appearance and disappearance as something that can be experienced every day, as well as the shadowy realm of the spirit world, is life-determining for them and shapes all areas of life. The spirits are responsible for the constant change in the world and therefore have to be respected, honored and in order to have a positive influence on events to be tempered.

The “transformation” of the poisonous cassava into edible products also plays a major role in the beliefs of these people.

rites

The Puinave society formed a ritual hierarchy with social and religious rites. a. include boys 'initiation and girls' fertility initiatives, accompanied by fasting , sexual abstinence, hallucinogens, and the conveyance of myths.

The Yurupari festival

Yurupari is an important rite that restores the balance between all beings and the connection to the ancestors, in which Túpana is honored and Yopinai is banned. Food and drinks are excessively prepared for the festival. a. Yaraque , a drink made from cassava and water, and Pai , a drink made from fermented cassava and Ñame . During the festival, the wooden copies of the sacred wind instruments, low-pitched trumpets (cuhay) and light-voiced flutes (majuari) are played. The festival includes initiation rituals in which boys leave the world of women and children and take on their duties in the world of men. This initiation includes prior fasting, sexual abstinence, hallucinogenic drugs, instruction in mythology, rituals and the use of sacred wind instruments. Women and children have to leave the village on the morning of the initiation ritual after blowing the holy trumpets. In this ceremony, the initiates are violently beaten with rods to which curagua cords (Ananas ananasoides) are stuck using Peraman ( Cerillo ). This is intended to strengthen the willpower of the boys and the fertility of nature. From sunset until the early morning there is dancing, a lot of eating and drinking. It belongs to the world heritage of UNESCO .

Christian proselytizing

The goal of both Catholic and Evangelical missionaries was to eradicate all aspects of the native belief system and to train native pastors.

Until the middle of the 20th century, the Puinave were largely resistant to missionary work, stable in their belief in spirits and in their social structures. With their nomadic way of life, they repeatedly withdrew from Western influences.

In 1943, the evangelical missionary Sofia Müller of German descent from the New Tribes Mission (Misión Nuevas Tribus) came to the Puinave to convert them. Before that she was successful with the Kuripako in Colombia and with the Baniwa . She brought the Puinave back to their traditional territory, settled them in villages and encouraged them to stop working for the rubber traders who exploited their labor. She later founded a New Tribes Mission in San Fernando de Atabapo, where the Puinave children were taught the fundamentalist version of the New Testament of the New Tribes Mission in their own language. With her anti-Catholic redemption sermons, the missionary succeeded in getting the majority of the Indians to their side. For the Puinave evangelicalism was a kind of resistance to the predominance of the Criollos.

Most of the young people of the Puinave today have lost knowledge of their cultural and religious traditions.

See also

literature

- Nancy Flowers : Puinave. In: Encyclopedia of Word Cultures. Volume 7, Boston 1994, p. 281.

- Curt Nimuendajú : Reconhecimento dos ríos Içána, Avari, e Uaupés, março a julho de 1927. Apontamentos lingüísticos. In: Journal de la Société des Américanistes 44. 1955, pp. 149–178.

- Theodor Koch-Grünberg : From the Roraíma to the Orinoco. Results of a trip to northern Brazil and Venezuela in the years 1911–1913 . Stuttgart 1923.

- JM Rozzo: La fiesta del diablo entre los Puinave. In: Boletín de Arqueología. 1-3, 1945, p. 241ff.

- Gloria Triana : Efectos de contacto en la adaptación y patrones de substencia tradicionales: Los Puinave del Inírida. In: Boletín de Antropología. Medellin 1983.

- Gloria Triana: Puinave. In: Introducción a la Colombia amerindia. Instituto Colombiano de Antropología (ICAN), Bogotá 1987.

- Hermann von Waldegg : Indians of the Upper Orinoco. In: Proceedings of the 8th American Scientific Congress. Volume 2, Washington 1942.

- Johannes Wilbert : Indios de la region Orinoco-Ventuari . Caracas 1966.

- Otto Zerries : Algunas Noticias Etnológicas Acerca de los Indígenas Puinave. In: Boletín Indigenista Venezolano. 9, Caracas 1965.

Individual evidence

- Main reference: Wilbert - Indios de la région Orinoco-Ventuari

- ↑ Nancy Flowers : Puinave. In: Encyclopedia of Word Cultures. Volume 7, Boston 1994, p. 281.

- ^ Merritt Ruhlen : A Guide to the World's Languages. Edward Arnold, London / Melbourne / Auckland 1991.

- ↑ RMW Dixon, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald : Máku. In: The Amazonian Languages. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1999, p. 361.

- ↑ a b c Gloria Triana: Puinave. In: Introducción a la Colombia amerindia. Instituto Colombiano de Antropología (ICAN), Bogotá 1987, pp. 681ff.

- ↑ Jonathan D. Hill : Los missionares y la fronteras. In: America indigena. Volume 44, 1984, p. 187.

- ^ Otto Zerries : Algunas Noticias Etnológicas Acerca de los Indígenas Puinave. In: Boletín Indigenista Venezolano. 9, Caracas 1965, 31.

- ↑ Note: The monkey is a culture bringer in South American mythology

- ↑ Note: In a narrative variant, Dukjin is the ailing and murdered Túpana, who comes back to life strengthened from dried bones.

- ↑ Note: Yopinai is in a narrative variant Maunduddua, one of the sisters of Túpana.

- ↑ Johannes Wilbert: Indios de la région Orinoco-Ventuari . Caracas 1966, page 101ff.

- ↑ Nancy Flowers: Puinave.

- ↑ Puinave. ( Memento of January 5, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) at: orinoco.org

- ↑ Koch-Grünberg

- ↑ Waldegg

- ↑ Rozzo

- ↑ Everyculture.com

Web links

- Puinave. ( Memento of January 5, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) at: orinoco.org

- Everyculture.com: Puinave

- People groups of Colombia. ( Memento of January 9, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) on: peoplegroups.org

- Christrex.org

- photos